Quatrain Form in English Folk Verse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Editor's Introduction

Editor’s Introduction: Scansion DAVID NOWELL SMITH _______________________ I would like to start from an intuition.1 This might seem an abuse of editorial privilege, and indeed might strike one as more generally tendentious: is an issue on ‘scansion’ the place for discussing one’s intuitions at all? For a start, it contravenes quite brazenly the strict separation between description and performance, lain down most powerfully by John Hollander well over half a century ago. For Hollander, a ‘descriptive’ system of scansion would aim at presenting schematically the whole ‘musical’ structure of a poem, whether this consists, in any particular case, of the prosodic features of the language in which it is written, the arrangement of elements completely foreign to that language (syllable counting in English verse for example), or even the arrangement of type on a page. A performative system of scansion, on the other hand, would present a series of rules governing a locutionary reading of a particular poem, before a real or implied audience. It would end up by describing not the poem itself, but the unstated canons of taste behind the rules. Performative systems of scansion, disguised as descriptive ones, have composed all but a few of the metrical studies of the past. Their subjectivity is far more treacherous than even that of reading poems into oscilloscopes and claiming that the image produced describes, or even is, the true poem.2 1 My great thanks to Ewan Jones on his comments on an earlier draft of this introduction. 2 John Hollander, ‘The Music of Poetry’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism vol. -

Rubai (Quatrain) As a Classical Form of Poetry in Persian Literature

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 4, Apr – 2018 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 30/04/2018 Rubai (Quatrain) as a Classical Form of Poetry in Persian Literature Ms. Mina Qarizada Lecturer in Samangan Higher Education, Samangan, Afghanistan Master of Arts in English, Department of English Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India Email – [email protected] Abstract: Studying literature, including poetry and prose writing, in Afghanistan is very significant. Poetry provides some remarkable historical, cultural, and geographical facts and its literary legacy of a particular country. Understanding the poetic forms is important in order to understand the themes and the styles of the poetry of the poets. All the Persian poets in some points of the time composed in the Rubai form which is very common till now among the past and present generation across Afghanistan. This paper is an overview of Rubai as a classical form of Poetry in Persian Literature. Rubai has its significant role in the society with different stylistic and themes related to the cultural, social, political, and gender based issues. The key features of Rubai are to be eloquent, spontaneous and ingenious. In a Rubai the first part is the introduction which is the first three lines that is the sublime for the fourth line of the poem. It represents the idea if sublet, pithy and clever. It also represents the poets’ literary works, poetic themes, styles, and visions. Key Words: Rubai, Classic, Poetry, Persian, Literature, Quatrain, 1. INTRODUCTION: Widespread geography of Persian speakers during the past centuries in the history of Afghanistan like many other countries, it can be seen and felt that only great men were trained in the fields of art and literature. -

The Play of Memory and Imagination in the Arena of Performance: an Attempt to Contextualise the History and Legend of Amar Singh

The Play of Memory and Imagination in the Arena of Performance: An Attempt to Contextualise the History and Legend of Amar Singh Rathore as taken forward by various Performing Arts First Six-Monthly Report Tripurari Sharma This report attempts to compile and analyse certain aspects that have come to the fore while exploring the various dimensions that emerge from the subject of study. It is true, that Amar Singh as a character has been celebrated in the Folk Performing Arts, like, Nautanki, Khayal and Puppetry. However, that is not all. There are also songs about him and some of the other characters who are part of his narrative. Bards also tell his story and each telling is a distinct version and interpretation of him and his actions. As his presence expands through various cultural expressions of Folklore, it seems necessary to explore the varying dimensions that have enabled this legend construct. A major challenge and delight in this research has been the discovering of material from various sources, not in one place and a lot by interaction and engaging with artists of various Forms. Books, that deal with History, Cultural Studies, Folk poetry, Life styles of Marwar and Rajputs, Mughal Court, Braj Bhasha and Folklore have been studied in detail. The N.M.M.L. has provided much material for reading. This has facilitated, thinking, formulating connections with the Legend, Society and Performative Arts. There have been discussions with artists engaged with Puppetry and Nautanki. Some of them have been preliminary in nature and some fairly exhaustive. Archival material of some senior artists has been examined and more is in process. -

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There are two general forms we will concern ourselves with: verse and prose. Verse is metered, prose is not. Poetry is a genre, or type (from the Latin genus, meaning kind or race; a category). Other genres include drama, fiction, biography, etc. POETRY. Poetry is described formally by its foot, line, and stanza. 1. Foot. Iambic, trochaic, dactylic, etc. 2. Line. Monometer, dimeter, trimeter, tetramerter, Alexandrine, etc. 3. Stanza. Sonnet, ballad, elegy, sestet, couplet, etc. Each of these designations may give rise to a particular tradition; for example, the sonnet, which gives rise to famous sequences, such as those of Shakespeare. The following list is taken from entries in Lewis Turco, The New Book of Forms (Univ. Press of New England, 1986). Acrostic. First letters of first lines read vertically spell something. Alcaic. (Greek) acephalous iamb, followed by two trochees and two dactyls (x2), then acephalous iamb and four trochees (x1), then two dactyls and two trochees. Alexandrine. A line of iambic hexameter. Ballad. Any meter, any rhyme; stanza usually a4b3c4b3. Think Bob Dylan. Ballade. French. Line usually 8-10 syllables; stanza of 28 lines, divided into 3 octaves and 1 quatrain, called the envoy. The last line of each stanza is the refrain. Versions include Ballade supreme, chant royal, and huitaine. Bob and Wheel. English form. Stanza is a quintet; the fifth line is enjambed, and is continued by the first line of the next stanza, usually shorter, which rhymes with lines 3 and 5. Example is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. -

The Poetry Handbook I Read / That John Donne Must Be Taken at Speed : / Which Is All Very Well / Were It Not for the Smell / of His Feet Catechising His Creed.)

Introduction his book is for anyone who wants to read poetry with a better understanding of its craft and technique ; it is also a textbook T and crib for school and undergraduate students facing exams in practical criticism. Teaching the practical criticism of poetry at several universities, and talking to students about their previous teaching, has made me sharply aware of how little consensus there is about the subject. Some teachers do not distinguish practical critic- ism from critical theory, or regard it as a critical theory, to be taught alongside psychoanalytical, feminist, Marxist, and structuralist theor- ies ; others seem to do very little except invite discussion of ‘how it feels’ to read poem x. And as practical criticism (though not always called that) remains compulsory in most English Literature course- work and exams, at school and university, this is an unwelcome state of affairs. For students there are many consequences. Teachers at school and university may contradict one another, and too rarely put the problem of differing viewpoints and frameworks for analysis in perspective ; important aspects of the subject are omitted in the confusion, leaving otherwise more than competent students with little or no idea of what they are being asked to do. How can this be remedied without losing the richness and diversity of thought which, at its best, practical criticism can foster ? What are the basics ? How may they best be taught ? My own answer is that the basics are an understanding of and ability to judge the elements of a poet’s craft. Profoundly different as they are, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dickinson, Eliot, Walcott, and Plath could readily converse about the techniques of which they are common masters ; few undergraduates I have encountered know much about metre beyond the terms ‘blank verse’ and ‘iambic pentameter’, much about form beyond ‘couplet’ and ‘sonnet’, or anything about rhyme more complicated than an assertion that two words do or don’t. -

A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 4-16-1983 A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur Jay Curlin Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Curlin, Jay, "A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur" (1983). Honors Theses. 209. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CLOSE LOOK AT TWO POEMS BY RICHARD WILBUR Jay Curlin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Honors Program Ouachita Baptist University The Department of English Independent Study Project Dr. John Wink Dr. Susan Wink Dr. Herman Sandford 16 April 1983 INTRODUCTION For the past three semesters, I have had the pleasure of studying the techniques of prosody under the tutelage of Dr. John Wink. In this study, I have read a large amount of poetry and have studied several books on prosody, the most influential of which was Poetic Meter and Poetic Form by Paul Fussell. This splendid book increased vastly my knowledge of poetry. and through it and other books, I became a much more sensitive, intelligent reader of poems. The problem with my study came when I tried to decide how to in corporate what I had learned into a scholarly paper, for it seemed that any attempt.to do so would result in the mere parroting of the words of Paul Fussell and others. -

Apparently Irreligious Verses in the Works of Mawlana Rumi by Ibrahim

Apparently Irreligious Verses in the Works of Mawlana Rumi By Ibrahim Gamard About Dar-Al- Masnavi Mystics sometimes surprise or shock listeners by statements that appear on the surface The Mevlevi Order to be irreligious, heretical, blasphemous, or radically tolerant--but which are expressions Masnavi of profound wisdom when understood on a deeper level. This is, in part, due to the frustration of trying to communicate mystical understanding to those whose minds are Divan restricted by conventional thinking. It is part of the playful teaching style of some mystics Prose Works to use unconventional statements to open such minds to deeper truths. In the case of orthodox religious mystics, radical-sounding statement are consistently harmonious with Discussion Board religious precepts when undertood at the level intended. Contact Such is the case in the poetic works of Mawlânâ Rûmî, the great Muslim mystic of the Links 13th century C. E. His references to things forbidden to Muslims such as "idols," "wine," Home and "unbelief" are not particularly provocative, in most cases, because these were commonplace images used in Persian Sufi poetry centuries before his time, understood to be spiritual metaphors by educated Persian listeners and readers. Nevertheless, the use of such imagery has continued to be misunderstood by Muslims and non-Muslims down to the present time. Further confusion has been caused by current popularizers of his poetry, who are eager to portray Mawlânâ as a radical mystic who defied "fundamentalist" Muslim authorities by teaching heretical doctrines, drinking alcoholic beverages, welcoming students affiliated with other religions, and so on. As a result, some of Mawlânâ's major teachings are all too often not understood correctly. -

ED 105 498 CS 202 027 Introduction to Poetry. Language Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 498 CS 202 027 TITLE Introduction to Poetry. Language Arts Mini-Course. INSTITUTION Lampeter-Strasburg School District, Pa. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 13p.; See related documents CS202024-35; Product of Lampeter-Strasburg High School EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Course Descriptions; Course Objectives; *Curriculum Guides; Instructional Materials; *Language Arts; Literature; *Poetry; Secondary Education; *Short Courses IDENTIFIERS Minicourses ABSTRACT This language arts minicourse guide for Lampeter-Strasburg (Pennsylvania) High School contains a topical outline of an introduction to a poetry course. The guide includes a list of twenty course objectives; an outline of the definitions, the stanza forms, and the figures of speech used in poetry; a description of the course content .nd concepts to be studied; a presentation of activities and procedures for the classroom; and suggestions for instructional materials, including movies, records, audiovisual aids, filmstrips, transparencies, and pamphlets and books. (RB) U S Oh PAR TmENT OF HEALTH C EOUCATKIN WELFARE NAT.ONA, INSTITUTE OF EOUCATION Ch DO. Ls. 1 N THA) BE E 4 REPRO ^,,)I qAt L'e AS RECEIVED FROM 1' HI PE 4 sON OR ulICHLNIZA T ION ORIGIN :.' 4L, , T PO,N' s OF .IIE K OR OP .NICINS LiN .." E D DO NOT riFcE SSARL + RE PRE ,E % , Lr lat_ 4.% 00NAL INS T TUT e OF CD c D , .'`N POs. T 1C14 OR POLICY uJ Language Arts Mini-Course INTRODUCTION TO POETRY Lampeter-Strasburg High School ERM.SSION TO RE POODuCETHIS COPY M. 'ED MATERIAL HA; BEEN GRANTED BY Lampeter, Pennsylvania Lampeter-Strasburg High School TD ERIC AV) ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING P.t,EP AGREEMENTS .SiTH THE NATIONAL IN STTuTE Or EDUCATION FURTHER 1973 REPRO PUCTION OU'SIDE THE EPIC SYSTEMRE QUIRES PERMISS'ON OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER N O INTRODUCTION TO POETRY OBJECTIVES: 1. -

Ottava Rima and Novelistic Discourse

Ottava Rima and Novelistic Discourse Catherine Addison In “Discourse in the Novel,” Mikhail Bakhtin goes to some lengths to dis- tinguish novelistic from poetic discourse. And yet, as noted by Neil Roberts (1), he uses a poetic text, Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, as one of his prime examples of novelistic discourse (Bakhtin 322–24, 329). Bakhtin’s theory is that poetic genres are monologic, presupposing “the unity of the language system and . of the the poet’s individuality,” as opposed to the novel, which is dialogic, “heteroglot, multivoiced, multi- styled and often multi-languaged.” (264–65). This paper contends that, by Bakhtin’s own criteria, some verse forms are especially well designed for novelistic discourse. The form chosen for particular scrutiny is ottava rima, a stanza that has been used for narrative purposes for many cen- turies, originating in the Italian oral tradition of the cantastorie (Wilkins 9–10; De Robertis 9–15). Clearly, ottava rima could not have originated as an English oral form, for it requires too many rhymes for this rhyme-poor, relatively uninflected language. Using a heroic line—in Italian the hendecasyllabic, in English the iambic pentameter—the stanza’s rhyme scheme is ABABABCC. Thus it resembles the English sonnet in a sense, for it begins with an alternating structure and concludes with a couplet that is alien to both the rhymes and the rhyme pattern that precede it. As with this type of sonnet, a potential appears for a rupture in the discourse between the alternating structure and the couplet. Alternating verse tends to lean forward not to the next line but JNT: Journal of Narrative Theory 34.2 (Summer 2004): 133–145. -

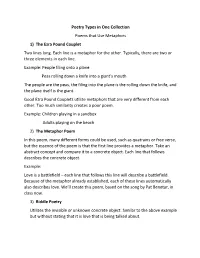

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems That Use Metaphors 1) the Ezra Pound Couplet Two Lines Long. Each Line Is a Metaphor for the Other

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems that Use Metaphors 1) The Ezra Pound Couplet Two lines long. Each line is a metaphor for the other. Typically, there are two or three elements in each line. Example: People filing onto a plane Peas rolling down a knife into a giant’s mouth The people are the peas, the filing into the plane is the rolling down the knife, and the plane itself is the giant. Good Ezra Pound Couplets utilize metaphors that are very different from each other. Too much similarity creates a poor poem. Example: Children playing in a sandbox Adults playing on the beach 2) The Metaphor Poem In this poem, many different forms could be used, such as quatrains or free verse, but the essence of the poem is that the first line provides a metaphor. Take an abstract concept and compare it to a concrete object. Each line that follows describes the concrete object. Example: Love is a battlefield – each line that follows this line will describe a battlefield. Because of the metaphor already established, each of these lines automatically also describes love. We’ll create this poem, based on the song by Pat Benetar, in class now. 3) Riddle Poetry Utilizes the invisible or unknown concrete object. Similar to the above example but without stating that it is love that is being talked about. Dylan Thomas portraits – this is a three line poem that asks a question which is answered by 4-6 word pairs ending in “ing”. Here is an example: Have you ever seen the rain? Life-giving, ground-soaking Mud-making, tires-spinning Haiku – Japanese three line poem with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. -

INTRODUCTION Tennyson, Hallam, and the Poem in October of 1833

INTRODUCTION Tennyson, Hallam, and the poem In October of 1833, Alfred Tennyson (he would not become “Lord” Tennyson for another fifty years) was living at the rectory in Somersby, Lincolnshire, where he had grown up. His father had died two years before, while Tennyson was studying at Cambridge; Alfred, although he was not the eldest son, had left the university without completing his degree in order to take on the duties of the male head of the household for his mother and his numerous younger siblings. Life with Tennyson’s father had been extremely difficult for the entire family, but it did not get much easier when he died. The Reverend George Tennyson had been the rector at Somersby; after his death his family, which was always in want of money, was faced with the probability that they would have to leave the rectory that had always been their home—as eventually they were compelled to do in 1837, an event commemorated in sections 100-105 of In Memoriam. One bright spot in Tennyson’s life at this time, and in that of his whole family, was Arthur Henry Hallam. Tennyson had met Hallam in the spring of 1829 at Cambridge, where they were both students at Trinity College, and they immediately formed the deepest and most profound friendship of Tennyson’s life. Tennyson’s childhood had been dark and unquiet, and he had not liked Cambridge at first, but with his newfound friend he flourished. Hallam was a sensitive and brilliant young man, later remembered not just by Tennyson but by many of his friends (including the future prime minister William Ewart Gladstone) as the member of their circle most clearly destined for 2 greatness. -

Tiruvalluvar.Pdf

9 788126 053216 9 788126 053216 TIRUVALLUVAR The sculpture reproduced on the end paper depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Śuddhodana the dream of Queen Māyā, mother of Lord Buddha. Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. This is perhaps the earliest available pictorial record of the art of writing in India. From: Nagarjunakonda, 2nd century A.D. Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE TIRUVALLUVAR by S. Maharajan Sahitya Akademi Tiruvalluvar: A monograph in English on Tiruvalluvar, eminent Indian philosopher and poet by S. Maharajan, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi: 2017, ` 50. Sahitya Akademi Head Office Rabindra Bhavan, 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi 110 001 Website: http://www.sahitya-akademi.gov.in Sales Office ‘Swati’, Mandir Marg, New Delhi 110 001 E-mail: [email protected] Regional Offices 172, Mumbai Marathi Grantha Sangrahalaya Marg, Dadar Mumbai 400 014 Central College Campus, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Veedhi Bengaluru 560 001 4, D.L. Khan Road, Kolkata 700 025 Chennai Office Main Guna Building Complex (second floor), 443, (304) Anna Salai, Teynampet, Chennai 600 018 First Published: 1979 Second Edition: 1982 Reprint: 2017 © Sahitya Akademi ISBN: 978-81-260-5321-6 Rs. 50 Printed by Sita Fine Arts Pvt. Ltd., A-16, Naraina Industrial Area Phase-II, New Delhi 110028 CONTENTS Introduction 7 The Times and Teachings of Tiruvalluvar 11 Translations and Citations 19 The Personality of Tiruvalluvar 25 Interpretation of the Kural 33 Word-worship 37 Sensual Love 41 Architectonics of the Kural 47 Some Glimpses of Tiruvalluvar 54 Valluvar at the World Vegetarian Congress 71 Valluvar’s Blue Print for the Evolution of Man 73 The Bard of Universal Man 98 APPENDIX Transliteration of Tamil words with diacritical marks 105 Bibliography 106 1 INTRODUCTION Though Tiruvalluvar lived about 2000 years ago, it does not seem he is dead.