Centralized Institutions and Their Inadequacies in the Bamboo Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harda District Madhya Pradesh

HARDA DISTRICT MADHYA PRADESH Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board North Central Region BHOPAL 2013 HARDA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE S. ITEMS STATISTICS No. 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geogeaphical area 3330 Sq.Km. ii) Administrative Divisions (As on 2012) 6 Number of Tehsils Number of Blocks 3 (Harda, Khirkia, Timarni) Number of Panchayats 211 village Panchayats Number of Villages 573 iii)Population (As per 2011 census) 570302 iv)Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1374.5 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY i) Major Physiographic Units 1. Satpura range and extension of Malwa Plateau in the south 2. Ridges (equivalent to Aravalli) 3. Alluvial plain in the north-east and central part ii) Major Drainage Narmada river and its tributaries, namely Ganjal river, Ajnal river, Sukni nadi, Midkul nadi, Dedra nadi, Machak nadi, Syani nadi and Kalimachak river. 3. LAND USE i) Forest area: 780.92 Sq. Km. ii) Net area sown: 1797.87 Sq. Km. iii) Cultivable area: 1845.32 Sq. Km. 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Black soils and ferruginous red lateritic soils, Sandy clay loam, sandy loam and clay loam. ( 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES Number of Area Structures (sq km) Dugwells 8140 307 Tube wells/Bore wells 1894 142 Tanks/Ponds 1 1 Canals 1 795 Other Sources 169 Net Irrigated Area 1414 Gross Irrigated Area 1414 7. NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (31.3.2013) No. of Dug Wells 9 No. of Piezometers 3 8 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Archaean Granite; Porcellanite/ quartzite/ schist (equivalent to Aravallies); Deccan Trap basaltic lava flows and older dolerite dykes/ sills and Recent laterite and alluvium 9 HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water Bearing Formation Alluvium, Deccan Trap and Pre-monsoon weathered granite. -

Species Diversity of Snakes in Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve

& Herpeto gy lo lo gy o : h C it u n r r r e O Fellows, Entomol Ornithol Herpetol 2014, 4:1 n , t y R g e o l s o e Entomology, Ornithology & Herpetology: DOI: 10.4172/2161-0983.1000136 a m r o c t h n E ISSN: 2161-0983 Current Research ResearchCase Report Article OpenOpen Access Access Species Diversity of Snakes in Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve Sandeep Fellows* Asst Conservator of forest, Madhya Pradesh Forest Department (Information Technology Wing), Satpura Bhawan, Bhopal (M.P) Abstract Madhya Pradesh (MP), the central Indian state is well-renowned for reptile fauna. In particular, Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve (PBR) regions (Districts Hoshangabad, Betul and Chindwara) of MP comprises a vast range of reptiles, especially herpetofauna yet unexplored from the conservation point of view. Earlier inventory herpetofaunal study conducted in 2005 at MP and Chhattisgarh (CG) reported 6 snake families included 39 species. After this preliminary report, no literature existing regarding snake diversity of this region. This situation incited us to update the snake diversity of PBR regions. From 2010 to 2012, we conducted a detailed field study and recorded 31 species of 6 snake families (Boidae, Colubridae, Elapidae, Typhlopidea, Uropeltidae, and Viperidae) in Hoshanagbad District (Satpura Tiger Reserve) and PBR regions. Besides, we found the occurrence of Boiga forsteni and Coelognatus helena monticollaris (Colubridae), which was not previously reported in PBR region. Among the recorded, 9 species were Lower Risk – least concerned (LR-lc), 20 were of Lower Risk – near threatened (LR-nt), 1 is Endangered (EN) and 1 is vulnerable (VU) according to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) status. -

Forest of Madhya Pradesh

Build Your Own Success Story! FOREST OF MADHYA PRADESH As per the report (ISFR) MP has the largest forest cover in the country followed by Arunachal Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Forest Cover (Area-wise): Madhya Pradesh> Arunachal Pradesh> Chhattisgarh> Odisha> Maharashtra. Forest Cover (Percentage): Mizoram (85.4%)> Arunachal Pradesh (79.63%)> Meghalaya (76.33%) According to India State of Forest Report the recorded forest area of the state is 94,689 sq. km which is 30.72% of its geographical area. According to Indian state of forest Report (ISFR – 2019) the total forest cover in M.P. increased to 77,482.49 sq km which is 25.14% of the states geographical area. The forest area in MP is increased by 68.49 sq km. The first forest policy of Madhya Pradesh was made in 1952 and the second forest policy was made in 2005. Madhya Pradesh has a total of 925 forest villages of which 98 forest villages are deserted or located in national part and sanctuaries. MP is the first state to nationalise 100% of the forests. Among the districts, Balaghat has the densest forest cover, with 53.44 per cent of its area covered by forests. Ujjain (0.59 per cent) has the least forest cover among the districts In terms of forest canopy density classes: Very dense forest covers an area of 6676 sq km (2.17%) of the geograhical area. Moderately dense forest covers an area of 34, 341 sqkm (11.14% of geograhical area). Open forest covers an area of 36, 465 sq km (11.83% of geographical area) Madhya Pradesh has 0.06 sq km. -

24 Part Xii-A Village and Town Directory

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 MADHYA PRADESH SERIES -24 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK HARDA VILLAGE AND TOWN directory DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MADHYA PRADESH 2011 SID RT TCI INDIA ES H S O ER MADHYA PRADESH A DISTRICT HARDA D e r o W d I KILOMETRES n I ! S 4 2 0 4 8 12 16 E ! o ! T D . ! R ! I C T ada T R N arm ! ! T ! ! ! ! ! R ! ! S ! ! R ! BOUNDARY : DISTRICT I ! I ! D HANDIYA ! C C.D.BLOCK ! ! ! " ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! T d TAHSIL ! ! a " ! b ! ga N ! ! n D H ha P R ( ! ! s HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT , TAHSIL , C.D.BLOCK ! o 5 ! E H 9 ! o ! T H A ! ! ! ! VILLAGES HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION ! ! ! Sodalpur ! ! O WITH NAME ! ! S ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- II, III ! ! ! A ! ! ! ! S J ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N ! ! ! ! ! (R ! ! ! ! HS 51 ! A ! ! ! C . D . B L O C K H A R D! A ! ! ! ! STATE HIGHWAY ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! TIMARNI ! H ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! C . D . B L O C K ! IMPORTANT ROADS ! ! HARDA ! ! ! A ! ! ! RS ! ! ! T I M A R N I ! ! ! ! ! Sodalpur N RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION : BROAD GAUGE ! ! ! P G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RIVER AND STREAM ! ! G ! 15 ! ! H ! S ! ! C J ! DEGREE COLLEGE ! ! A ! ! ! F G ! ! HOSPITAL ! ! ! B ! ! ! ! ! T ! o ! D ! B ! e A ! ! tu ! l ! ! ! ! ! REHATGAON ! ! D I ! ! ! ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S ! ! ! Rehatgaon A ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! T ! ! ! ! ! S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! i ! ! t ! ! tul ! ! ! Be ! o h ! T ! ! ! ! ! M a ! KHIRKIYA ! ! ! A R ! ! ! n C ! ! ! ! ! H i ! A ! S ! ! K R R ! ! ! ! R ! R ! ! . ! ! ! ! ! I ! SIRALI ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ( ! wa R! ! ! d ! an J Sirali ! ! om Kh ! r ! ! F ! C ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! TAHSIL w ! d C . -

Sohagpur Assembly Madhya Pradesh Factbook | Key Electoral Data of Sohagpur Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : http://www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/MP-138-0617 ISBN : 978-93-87189-93-5 First Edition : June, 2017 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © 2017 Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All right reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014, 2013, 2009 and 2008 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-25 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographic 4 Population Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 26-27 Population Size | Sex Ratio (Total & 0-6 Years) | Religious Population | Social Population | Literacy Rate | Work Participation Electoral Features Important Dates of Last Elections -

Brief Industrial Profile of Betul District Madhya Pradesh

lR;eso t;rs Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Betul District Madhya Pradesh Carried out by MSME -Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) 10, Pologround Industrial Estate, Indore-452015( MP) Phone : 0731-2490149,2421730 Fax: 0731-2421037 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmeindore.nic.in 1 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 4 1.4 Forest 4 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2. District at a glance 4-5 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in Betual District 6 3. Industrial Scenario of Betul District 6 3.1 Industry at a Glance 7 3.2 Year Wise Trend of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units 8 In The District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 8 3.5 Major Exportable Item 8 3.6 Growth Trend 8 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 8 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 8 3.8.1 Major Exportable Item 8 3.8.2 Growth Trend 8 3.9 Service Enterprises 9 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 9 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 9 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 9 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 9 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 10 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Betul District 1. General Characteristics of the District. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Hoshangabad District

Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 3 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2. District at a glance 4-5 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Hoshangabad 6 3. Industrial Scenario Of Hoshangabad 6 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 6-7 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 7 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 7 3.5 Major Exportable Item 7 3.6 Growth Trend 7 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 7 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 7 3.8.1 List of the units in Hoshangabad & near by Area 7 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 7 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 7 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 8 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 8 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of meeting 8 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 9 2 BRIEF INDUSTRIAL PROFILE OF HOSHANGABAD DISTRICT 1. General Characteristics of the District The district takes its own name from the head quarters town Hoshangabad which was founded by "SULTAN HUSHANG SHAH GORI", the second king of Mandu (Malwa) in ealry 15th century. 1.1 Location & Geographical Area. Hoshangabad district lies in the central Narmada Valley covering an area of 5408.23 sq.km, and lies on the northern fringe of the Satpura Plateau. -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Region Wise Distribution of Industries in MP

INVENTORY OF HAZARDOUS WASTE GENERATED IN MADHYA PRADESH YEAR : 2012013333 ––– 2014 *** Submitted to CPCB *** __________________________________________________________________________________ M.P. Pollution Control Board PBX : + 91 (0755) 2464428/2466191 Paryawaran Parisar, E-5 Sector FAX : + 91 (0755) 2463742 Arera Colony, Bhopal – 462 016 web : www.mppcb.nic.in India E-mail : [email protected] General description of Madhya Pradesh 1 Madhya Pradesh is the second largest Indian State, covering 9.5% of the area of the country. Industries in Madhya Pradesh, are largely natural resources driven. It has abundant natural wealth in the form of Lime Stone, Coal, Bauxite, Iron, Diamond ore, Silica and so on and crops like Soya, Cotton, Wheat Paddy etc. The State has a strong industrial setup in the sectors such as Auto, Textile, Cement and Soya/Textile processing units. The Major Central Public Sectors Undertaking like :- BHEL Bhopal, National Fertilizer Ltd. Vijaypur Dist. Guna, Security Paper Mill Hoshangabad, Currency Printing Press, Bank Note Press, Dewas, Opium Alkaloid Factory Neemuch, Ordnance Factory Itarsi, Gun Carriage Factory Jabalpur and Nepa Mills, Nepa Nagar etc. are also located in the State . In Madhya Pradesh there are about 14,000 industries/project located in different parts of the State. Out of the above 1,426 industries are registered with. M.P. Pollution Control Board issued authorization to 1568 units under Hazardous Waste (Management, Handling & Trans-boundary Movement) Rules 2008. Out of these 598 are Large/Medium 2 scale industries, where as 970 are Small Scale units. The main source of generation of hazardous waste from most of the industries is waste/spent oil whereas the manufacturing process also contribute to the generation of hazardous waste to a considerable extent. -

District Census Handbook, Hoshangabad, Part XIII-B, Series-11

• 'lTtT XllI-v ~~t(ot;rr (fiT SlT'-Ifq ... m~m • ~. '". ~, ~ $l4Iief;ll", ~ ~, Ifi\tiOf;ll" ~. 1981 CENSUS-PUBUCATION PLAN ( 198 / Census Publications, Series J I in All India Series will be published ill tif! folltJw~ "Mfs) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PUBLICATIONS Part I-A Administration Report-Enumeration Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation Part II-A General Population Tables Part II-B Primary Census Abstract Part III Gel1eral Economic Tables Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part V Migration Tables Part VI Fertility Tables P;:trt VII Tables on Houses and Disabled Population Part VIn Household Tables Part IX Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part X-A Town Directory Part X-B Survey Reports on selected Towns Part X-C Survey Reports on selected Villages Part XI Ethnographic Notes and special studies on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part XII Census Atlas Paper 1 of 1982 Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes an1 Scheduled Tribes Paperl of 1984 Household Population by Religion of H~ad of Household STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Part XIII-A and B District C~n5us Handbook for each of the 45 districts in the State (Village and Town Directory and Primary Census Abstract) CONTENTS 1 srfCfifi"A Foreword I-IV 2 ~T Preface V-VI 3 ~ Cfil i{CffiT District Map 4 q~~~ adCfi~ Important Statistics VII Analytical Note IX-XXXXIV 5 f?tffl'fUTTt'fCfi :-~) ~m~lI'Rlf'fi f~q-urr; ar~~f"ffi \iflfor Notes and Explanations: list of Scheduled atT~ ar:!.~f",cr \iiif\iflfcr 'liT ~"fr Castes and Scheduled Tribes Order ( ij'1!I'1WT). -

Climate Change Publications Catalogue DA.Pdf

August 2021 1 www.devalt.org August 2021 Note Please note that these papers are generally reports of work done on projects the primary purpose of which was to deliver results on the ground and under stringent reporting deadlines. Although every effort is made by Development Alternatives staff to ensure the accuracy and rigour of their analysis and recommendations, they were intended to be distributed rapidly and while they have received careful editing, many of them have not been formally peer-reviewed to the standards required for academic research. FOR COPIES, PLEASE WRITE TO: Resource Centre DA <[email protected]> 2 www.devalt.org August 2021 Development Alternatives and TARA CATALOUGE OF PUBLICATIONS Climate Change Serial no. Type of Resource Page No. 1. Publications 4 2. Webinars 20 3. Blogs 21 4. DA Newsletters 22 5. External Publications 27 6. Audio/Visual 34 3 www.devalt.org August 2021 Publications Title: Landscape Assessment of State-Level Climate Financing Options Year of Publication: 2020 Pages: 18 Keywords: Climate, Financing, Energy Abstract: The report will assist practitioners in understanding the flow of climate change mitigation funds from source to destination. Hence, the report emphasizes more on the financial intermediaries and the availability of different sources of funds for development of clean energy and energy efficient projects in India. URL: https://bit.ly/34sKC79 Title: Landscape Assessment of State-Level Climate Financing Options Year of Publication: 2020 Pages: 46 Keywords: Mitigation Finance, Clean Energy Projects, Climate Abstract: The report focuses on the financing aspects of clean energy projects in India with the help of substantial evidence and examples. -

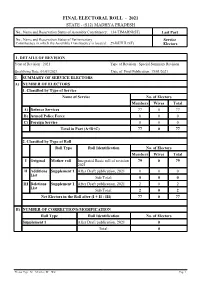

Service Electors Voter List

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 STATE - (S12) MADHYA PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 134-TIMARNI(ST) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 29-BETUL(ST) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2021 Type of Revision : Special Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2021 Date of Final Publication: 15/01/2021 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 77 0 77 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 0 0 0 Total in Part (A+B+C) 77 0 77 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Integrated Basic roll of revision 79 0 79 2021 II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 2 0 2 List Sub Total: 2 0 2 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 77 0 77 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2021 of Assembly Constituency 134-TIMARNI (ST), (S12) MADHYA PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) Assam Rifles 1 HUKUM