Vocal Mimicry in the Spotted Bowerbird Ptilonorhynchus Maculatus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Variation in Bower Decorating Style Among Male Bowerbirds

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 3042-3046, May 1986 Population Biology Animal art: Variation in bower decorating style among male bowerbirds Amblyornis inornatus (cultural rnlsson/geographic variadon/behavior) JARED DIAMOND Physiology Department, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Contributed by Jared Diamond, December 30, 1985 ABSTRACT Courtship bowers of the bowerbird Ambly- BACKGROUND ornis inornatus, the most elaborately decorated structures Bowers are avenues, huts, or towers of sticks decorated with erected by an animal other than humans, vary geographically objects such as fruits, flowers, mushrooms, and stones. and individually. Bowers in the south Kumawa Mountains are Males often hold a decoration in their bill while displaying to tall towers of sticks glued together, resting on a circular mat of a female, and experiments confirm that bower structure and dead moss painted black, and decorated with dull objects such decorations influence females' choice of mate (7). Whereas as snall shells, acorns, and stones. Bowers in the Wandamen males are polygynous and contribute nothing to the female Mountains are low woven towers covered by a stick hut with an after copulation, females perform the whole effort ofbuilding entrance, resting on a green moss mat and decorated with a nest and rearing the young. Species comparisons show that colorful objects such as fruits, flowers, and butterfly wings. male bowerbirds with duller ornamental plumage build fan- Young males build simpler bowers, and adult males differ cier bowers (4, 8). Thus, during bowerbird evolution the among themselves. Experiments with poker chips of seven female's attention has been transferred from ornaments ofthe colors offered as decorations showed that individual birds male's body to those ofhis bower. -

House Crow E V

No. 2/2008 nimal P A e l s a t n A o l i e t 1800 084 881 r a t N Animal Pest Alert F reecall House Crow E V I The House Crow (Corvus splendens) T is also known as the Indian, Grey- A necked, Ceylon or Colombo Crow. It is not native to Australia but has been transported here on numerous occasions on ships. The T N House Crow has signifi cant potential to establish O populations in Australia and become a pest, so it is important to report any found in the wild. NOTN NATIVE PHOTO: PETRI PIETILAINEN E Australian Raven V I T A N Adult Immature PHOTO: DUNCAN ASHER / ALAMY PHOTO: IAN MONTGOMERY Please report all sightings of House Crows – Freecall 1800 084 881 House Crow nimal P A e l s a t n A o l i e t 1800 084 881 r a Figure 1. The distribution of the House Crow including natural t N (blue) and introduced (red) populations. F reecall Description Distribution The House Crow is 42 to 44 cm in length (body and tail). It has The House Crow is well-known throughout much of its black plumage that appears glossy with a metallic greenish natural range. It occurs in central Asia from southern coastal blue-purple sheen on the forehead, crown, throat, back, Iran through Pakistan, India, Tibet, Myanmar and Thailand to wings and tail. In contrast, the nape, neck and lower breast southern China (Figure 1). It also occurs in Sri Lanka and on are paler in colour (grey tones) and not glossed (Figure 3). -

Nest, Egg, Incubation Behaviour and Parental Care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis Germana

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 18–23 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36018023 Nest, egg, incubation behaviour and parental care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana Richard H. Donaghey1, 2*, Donna J. Belder3, Tony Baylis4 and Sue Gould5 1Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan 4111 QLD, Australia 280 Sawards Road, Myalla TAS 7325, Australia 3Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 4628 Utopia Road, Brooweena QLD 4621, Australia 5269 Burraneer Road, Coomba Park NSW 2428, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana, recently elevated to species status, is endemic to montane forests on the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. The polygynous males in the Yopno Urawa Som Conservation Area build distinctive maypole bowers. We document for the first time the nest, egg, incubation behaviour, and parental care of this species. Three of the five nests found were built in tree-fern crowns. Nest structure and the single-egg clutch were similar to those of MacGregor’s Bowerbird A. macgregoriae. Only the female Huon Bowerbird incubated. Mean length of incubation sessions was 30.9 minutes and the number of sessions daily was 18. Diurnal incubation constancy over a 12-hour day was 74%, compared with a mean of ~70% in six other members of the bowerbird family. The downy nestling resembled that of MacGregor’s Bowerbird. Vocalisations of a female Huon Bowerbird at a nest with a nestling -

Male Intelligence Influences Male Mating Success in the Satin

Male intelligence influences male mating success in the satin bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) Jason Keagy1, Jean-François Savard2, and Gerald Borgia1,2 1Behavior, Ecology, Evolution and Systematics Program 2Biology Department University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 Introduction: Results: The relationship between intelligence and Red Coverage Experiment: Red on average sexual selection has not been directly was covered significantly more than blue (t=- examined, although several studies have 2.37, P=0.047), and green was intermediate examined the relationship between sexual in coverage. Tiles in the positions close to selection and brain size1,2,3. Male satin the bower (for example red and blue in bowerbirds, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus, Figure 1) were covered very little regardless have complex sexual displays that involve of color. For males with red in one of these building a stick bower on the ground, positions, red coverage did not predict decorating the bower with colored objects4, mating success. However, for those males and courting females at the bower with a with the red tile in the outer position, male complex dance during which they mimic mating success was predicted by red 5 2 other species of birds and vary in their Figure 1. Layout of experiment. Dotted line segments are coverage (R =0.65, P=0.005; Figure 4). 20 cm long. ability to react to female signals of Barrier Experiment: 6 discomfort . Males destroy their rivals’ The amount of time it took for males to 7 bowers and steal decorations from them . remove the clear barrier significantly Males do not mature until seven years of predicted their mating success (R2=0.29, age, and as juveniles they learn and P=0.005; Figure 5). -

The Australian Raven (Corvus Coronoides) in Metropolitan Perth

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1997 Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth P. J. Stewart Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, P. J. (1997). Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids

72 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 72-82 Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids CLARE LAWRENCE School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 5, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 (Email: [email protected]) Summary Some vocal characteristics and call variation in the Australian crows and ravens were studied by sonagraphic analysis of tape-recorded calls. The species grouped according to mean maximum emphasised frequency (Australian Raven Corvus coronoides, Forest Raven C. tasmanicus and Torresian Crow C. orru with lower-freq_uency calls, versus Little Raven C. mellori and Little Crow C. bennetti with higher-frequency calls). The Australian Raven had significantly longer syllables than the other species, but there were no significant interspecific differences in intersyllable length. Calls of Southern C.t. tasmanicus and Northern Forest Ravens C.t. boreus did not differ significantly in any measured character, except for normalised syllable length (phrases with the long terminal note excluded). Northern Forest Ravens had longer normalised syllables than Tasmanian birds; Victorian birds were intermediate. No evidence was found for dialects or regional variation within Tasmania, and calls from the mainland clustered with those from Tasmania. Introduction Owing largely to the definitive work of Rowley (1967, 1970, 1973a, 1974), the diagnostic calls of the Australian crows and ravens Corvus spp. are well known in descriptive terms. The most detailed studies, with sonagraphic analyses, have been on the Australian Raven C. coronoides and Little Raven C. mellori (Rowley 1967; Fletcher 1988; Jurisevic 1999). The calls of the Torresian Crow C. orru and Little Crow C. bennetti have been described (Curry 1978; Debus 1980a, 1982), though without sonagraphic analyses. -

Ultimate Papua New Guinea Ii

The fantastic Forest Bittern showed memorably well at Varirata during this tour! (JM) ULTIMATE PAPUA NEW GUINEA II 25 AUGUST – 11 / 15 SEPTEMBER 2019 LEADER: JULIEN MAZENAUER Our second Ultimate Papua New Guinea tour in 2019, including New Britain, was an immense success and provided us with fantastic sightings throughout. A total of 19 Birds-of-paradise (BoPs), one of the most striking and extraordinairy bird families in the world, were seen. The most amazing one must have been the male Blue BoP, admired through the scope near Kumul lodge. A few females were seen previously at Rondon Ridge, but this male was just too much. Several males King-of-Saxony BoP – seen displaying – ranked high in our most memorable moments of the tour, especially walk-away views of a male obtained at Rondon Ridge. Along the Ketu River, we were able to observe the full display and mating of another cosmis species, Twelve-wired BoP. Despite the closing of Ambua, we obtained good views of a calling male Black Sicklebill, sighted along a new road close to Tabubil. Brown Sicklebill males were seen even better and for as long as we wanted, uttering their machine-gun like calls through the forest. The adult male Stephanie’s Astrapia at Rondon Ridge will never be forgotten, showing his incredible glossy green head colours. At Kumul, Ribbon-tailed Astrapia, one of the most striking BoP, amazed us down to a few meters thanks to a feeder especially created for birdwatchers. Additionally, great views of the small and incredible King BoP delighted us near Kiunga, as well as males Magnificent BoPs below Kumul. -

Male Courtship Vocalizations As Cues for Mate Choice in the Satin Bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus Violaceus)

MALE COURTSHIP VOCALIZATIONS AS CUES FOR MATE CHOICE IN THE SATIN BOWERBIRD (PTILONORHYNCHUS VIOLACEUS) CHRISTOPHER A. LOFFREDO AND GERALD BORGIA Departmentof Zoology,University of Maryland,College Park, Maryland 20742 USA AI3STRACT.--MaleSatin Bowerbirds(Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) court femalesat specialized structurescalled bowers. Courtship includes a complexpattern of vocalizationsin which a broad-band,mechanical-sounding song is followed by interspecificmimicry. We studiedthe effect of male courtshipdisplays on male mating successin Satin Bowerbirds.Data from 2 yearsof field researchshowed low between-maledifferences in mechanicalcomponents of courtshipsong and high variability betweenmales in mimeticsinging. Older malessang longer and higher-qualitybouts of mimicry than did youngermales. In one year, courtship song featureswere correlatedwith male mating success.The resultssuggest that female SatinBowerbirds use male courtship vocalizations in their mate-choicedecisions. We discuss hypothesesabout assessment of male age and dominancefrom courtshipvocalizations and suggestthat thesesongs have evolvedas a result of selectionfor male displaycharacteristics that provide femaleswith information about the relative quality of prospectivemates. Re- ceived27 June1985, accepted20 September1985. MALESatin Bowerbirds(Ptilonorhynchus vio- ingnessto copulateor by flying away. Given laceus)build specializedstructures called bow- the complexity of male display and the atten- ers that are used as sites for courting females tion femalespay to displayingmales, -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

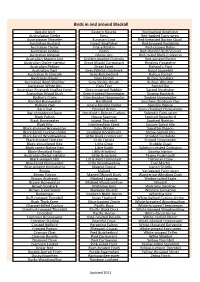

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Chapter 18 Evolution of Reproductive Behavior (1St Lecture)

Chapter 18 Evolution of reproductive behavior (1st lecture) The Satin Bowerbird has an unusual courtship ritual Male constructs an female elaborate “avenue” bower, contaiing colorful objects that he has collected. When a female arrives, he performs a energetic dance while emitting a medley of male buzzes, screeches and imitations of other bird songs. The female assesses the male based on: bower attributes, the male’s dance, and location of the bower If the female decides to mate with him, then she will enter his bower, copulate, and fly away, never to see him again. She will incubate her eggs and raise young on her own. The male will continue in this manner across the 8-month breeding season, mating with as many females as possible. The design of the bower varies greatly, both among and within species Playhouse bower Different populations of Amblyornis inoratus construct different types of bower, perhaps reflecting different “aesthetic tastes” of females within each population Maypole bower Evolutionary relationships among 14 of the 19 species of bowerbird, based on similarities in their mitochondrial cytochrome b gene Note that 2 bowerbird species share the ancestral trait of not building a bower Maypole builders Presumably, the hypothetical species Y built a Avenue simple bower. builders The ensuing adaptive radiation illustrates a fantastic example of divergent evolution What are the features of the bowerbird courtship ritual that represent evolutionary conundrums? The males make absolutely no parental investment Each male mates multiple