Communal Roosting in a Suburban Population of Torresian Crows (Corvus Orru)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House Crow E V

No. 2/2008 nimal P A e l s a t n A o l i e t 1800 084 881 r a t N Animal Pest Alert F reecall House Crow E V I The House Crow (Corvus splendens) T is also known as the Indian, Grey- A necked, Ceylon or Colombo Crow. It is not native to Australia but has been transported here on numerous occasions on ships. The T N House Crow has signifi cant potential to establish O populations in Australia and become a pest, so it is important to report any found in the wild. NOTN NATIVE PHOTO: PETRI PIETILAINEN E Australian Raven V I T A N Adult Immature PHOTO: DUNCAN ASHER / ALAMY PHOTO: IAN MONTGOMERY Please report all sightings of House Crows – Freecall 1800 084 881 House Crow nimal P A e l s a t n A o l i e t 1800 084 881 r a Figure 1. The distribution of the House Crow including natural t N (blue) and introduced (red) populations. F reecall Description Distribution The House Crow is 42 to 44 cm in length (body and tail). It has The House Crow is well-known throughout much of its black plumage that appears glossy with a metallic greenish natural range. It occurs in central Asia from southern coastal blue-purple sheen on the forehead, crown, throat, back, Iran through Pakistan, India, Tibet, Myanmar and Thailand to wings and tail. In contrast, the nape, neck and lower breast southern China (Figure 1). It also occurs in Sri Lanka and on are paler in colour (grey tones) and not glossed (Figure 3). -

The Australian Raven (Corvus Coronoides) in Metropolitan Perth

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1997 Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth P. J. Stewart Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, P. J. (1997). Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids

72 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 72-82 Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids CLARE LAWRENCE School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 5, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 (Email: [email protected]) Summary Some vocal characteristics and call variation in the Australian crows and ravens were studied by sonagraphic analysis of tape-recorded calls. The species grouped according to mean maximum emphasised frequency (Australian Raven Corvus coronoides, Forest Raven C. tasmanicus and Torresian Crow C. orru with lower-freq_uency calls, versus Little Raven C. mellori and Little Crow C. bennetti with higher-frequency calls). The Australian Raven had significantly longer syllables than the other species, but there were no significant interspecific differences in intersyllable length. Calls of Southern C.t. tasmanicus and Northern Forest Ravens C.t. boreus did not differ significantly in any measured character, except for normalised syllable length (phrases with the long terminal note excluded). Northern Forest Ravens had longer normalised syllables than Tasmanian birds; Victorian birds were intermediate. No evidence was found for dialects or regional variation within Tasmania, and calls from the mainland clustered with those from Tasmania. Introduction Owing largely to the definitive work of Rowley (1967, 1970, 1973a, 1974), the diagnostic calls of the Australian crows and ravens Corvus spp. are well known in descriptive terms. The most detailed studies, with sonagraphic analyses, have been on the Australian Raven C. coronoides and Little Raven C. mellori (Rowley 1967; Fletcher 1988; Jurisevic 1999). The calls of the Torresian Crow C. orru and Little Crow C. bennetti have been described (Curry 1978; Debus 1980a, 1982), though without sonagraphic analyses. -

Ultimate Papua New Guinea Ii

The fantastic Forest Bittern showed memorably well at Varirata during this tour! (JM) ULTIMATE PAPUA NEW GUINEA II 25 AUGUST – 11 / 15 SEPTEMBER 2019 LEADER: JULIEN MAZENAUER Our second Ultimate Papua New Guinea tour in 2019, including New Britain, was an immense success and provided us with fantastic sightings throughout. A total of 19 Birds-of-paradise (BoPs), one of the most striking and extraordinairy bird families in the world, were seen. The most amazing one must have been the male Blue BoP, admired through the scope near Kumul lodge. A few females were seen previously at Rondon Ridge, but this male was just too much. Several males King-of-Saxony BoP – seen displaying – ranked high in our most memorable moments of the tour, especially walk-away views of a male obtained at Rondon Ridge. Along the Ketu River, we were able to observe the full display and mating of another cosmis species, Twelve-wired BoP. Despite the closing of Ambua, we obtained good views of a calling male Black Sicklebill, sighted along a new road close to Tabubil. Brown Sicklebill males were seen even better and for as long as we wanted, uttering their machine-gun like calls through the forest. The adult male Stephanie’s Astrapia at Rondon Ridge will never be forgotten, showing his incredible glossy green head colours. At Kumul, Ribbon-tailed Astrapia, one of the most striking BoP, amazed us down to a few meters thanks to a feeder especially created for birdwatchers. Additionally, great views of the small and incredible King BoP delighted us near Kiunga, as well as males Magnificent BoPs below Kumul. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

On the Field Characters of Little and Torresian Crows in Central Western Australia. by PETER J

December ] CURRY: Field Characters of Crows 265 1978 (Wheelwright, H. W.) An Old Bushman 1861. Bush Wanderings of a Naturalist. London. Routledge, Warne and Routledge. Whittell, H . M., 1954. The Literature of Australian Birds. Perth. Paterson Brokensha. Wilson, Edward, 1858. On the Introduction of the British Song Bird. Transactions of the Philosophical Institute of Victoria 2, 77-88. Wilson, Edward, 1860. Letter to the Times, 22 September, 1860. (ZOOLOGICAL AND) ACCLIMATISATION SOCIETY OF VICTORIA 1861-1951 Papers (mostly minutes and reports) Vols. 1-13 (Xerox copies in library of Monash University, Clayton, Victoria). 1861-7. Annual reports, Answers to enquiries, report of dinner, rules and objects, etc. (Bound in Victorian pamphlets, nos. 32, 36, 49, 60 and 129 in LaTrobe Library, State Library of Victoria. 1872-8. Proceedings and reports of Annual Meetings, Vols. 1-5. On the Field Characters of Little and Torresian Crows in Central Western Australia. By PETER J. CURRY, 29 Canning Mills Road Kelmscott, W.A., 6111. The Little Crow Corvus bennetti and the Torresian Crow C. orru are evidently sympatric over a large part of northern and cen tral Australia and are notoriously difficult to separate in the field. Over their respective ranges, morphological similarities and indivi dual variation in size are such that some individuals are extremely difficult to identify even in the hand (Rowley, 1970). Despite various recent references which draw attention to the importance of call-notes and habits in field identification (Rowley, 1973; Readers' Digest, 1976), published information on the subject has generally been very brief. The notes which follow r~sult from field observations made in the Wiluna region of central Western Australia, during eighteen months of almost daily contact with both species. -

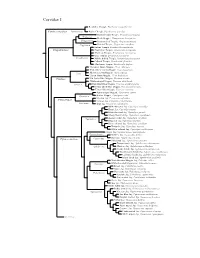

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Chick-Provisioning and Other Behaviour of a Pair of Torresian Crows Cmvus Orru

207 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 207-209 Chick-provisioning and other Behaviour of a Pair of Torresian Crows Cmvus orru DAVID SECOMB 21 Aberdeen Street, Katanning, Western Australia 6317 (Email: [email protected]) Summary Observations near Coffs Harbour (New South Wales) on one afternoon in week 3 of the nestling phase revealed that the presumed female Torresian Crow Corvus orru brooded for 35% of observation time (2.3 h), and both sexes fed the nestlings at a combined rate of 3.0 deliveries/ h ( n = 7). Both sexes defended the nest against potential predators, and the female performed an undulating return flight, with calling, after evicting a raptor. Introduction The breeding behaviour of the Torresian Crow Corvus orru has been studied (Rowley 1973), though in less detail than for some other Australian corvids, and little information has been added since then (Debus 1996). This paper describes an opportunistic observation of the parental behaviour of Torresian Crows on the North Coast of New South Wales in October 1996, made during a study of the Forest Raven C. tasmanicus (Secomb 2005b ). Study area and methods Observations of one Torresian Crow nest were made for 137 minutes on one day (26 October) on a small rural property near the village of Valla (30°36'S, 152°58'E), 40 km south of Coffs Harbour, NSW, between 1503 and 1720 h. As crows are shy around the nest, observations were made with the aid of a 20x telescope from a house 400 m away. The adults were sexed on the basis that only female Corvus species incubate or brood (Rowley 1973). -

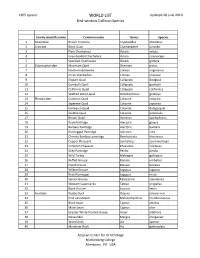

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Torresian Crow Corvus Orru Species No.: 692 Band Size: 10

Australian Bird Study Association Inc. – Bird in the Hand (Second Edition), published on www.absa.asn.au Torresian Crow Corvus orru Species No.: 692 Band size: 10 Morphometrics: The only subspecies in Australia is C.u. cecilae and its measurements are provided below: Adult Male Adult Female Wing: 315 – 382 mm 320 – 363 mm Tail: 179 – 214 mm 176 – 221 mm Bill (tip to skull): 57.5 – 66.1 mm 53.5 – 63.6 mm Weight: 430 – 670 g 430 – 650 g Ageing: Adult (3+) 2nd Immatures (2) 1st Immature (1) & Juvenile Bill: black; grey- black; grey-black: initially with pinkish base to lower mandible; Gape: black; blackish-pink; pink or reddish; Palate: black; blackish-pink; pink or reddish; Interramal skin: black; blackish-pink; pink; Iris: white, with pale blue hazel; blue-grey changing to brown by inner ring; three months of age; Remiges & rectrices: blackish with glossy as for adult; blackish-brown; greenish sheen grading to bluish-purple at tips; Juveniles undergo a partial moult to first immature plumage soon after fledging; First Immatures retain all or most juvenile remiges, greater primary coverts, alula and rectrices. Note that outer primaries and tail feathers differ in shape from adults – see illustration below; First immatures commence moult to second immature plumage, which is indistinguishable from adult plumage, at approximately one year old; Second immatures, identified by subtle differences in bare parts, attain full adult colouring in a complete moult commencing at the end of their second year. Thus adults aged (3+); Sexing: There is no plumage dimorphism, though adult males average larger than adult females; Incubation is by the female only. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

The 2008 Edition of the Adjutant. It Is, However, with a Touch of Sadness That I Write This Introduction to This Excellent, Rejuvenated and Revised Magazine

Welcome to the 2008 edition of The Adjutant. It is, however, with a touch of sadness that I write this introduction to this excellent, rejuvenated and revised magazine. Let me explain. Earlier this year it became clear that our sister society, the Royal Air Force Ornithological Society (RAFOS), was not able to guarantee future funding for Osprey, our joint magazine. The Committee of the Army Ornithological Society (AOS) quickly came to the conclusion that it did not have the necessary resources to ‘go it alone’ and decided that Osprey would no longer be published. I am fully aware that my predecessor, Ian Nason, spent much time and energy on encouraging the start of Osprey, the first edition of which appeared as my tenure as Chairman of the AOS began. Maybe the demise of Osprey is a sign for me to move on, but first I must thank the joint editors of Osprey from inception, Simon Strickland (AOS) and Mike Blair (RAFOS), for their magnificent achievements over the years in providing such a first class magazine. Actually I am not going to hand over, not yet, as we are certain that the way the AOS Bulletin has progressed under its current editor, Andrew Bray, gives us a cheaper alternative and one which I wish to promote. We therefore have decided, for 2008 at least, to provide a new single publication with two parts reflecting both the differences and the synergy between Osprey and The Bulletin. A vote at our AGM in the Summer confirmed that this new magazine would be entitled The Adjutant (which was last published in 2000), headed with our re-energised logo, the more upright Adjutant Stork.