Witches in Ghana Review by D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights Violations and Accusations of Witchcraft in Ghana Sara Pierre ABOUT CHRLP

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INTERNSHIP PROGRAM | WORKING PAPER SERIES VOL 6 | NO. 1 | FALL 2018 Human Rights Violations and Accusations of Witchcraft in Ghana Sara Pierre ABOUT CHRLP Established in September 2005, the Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) was formed to provide students, professors and the larger community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with the ways in which law affects some of the most compelling social problems of our modern era, most notably human rights issues. Since then, the Centre has distinguished itself by its innovative legal and interdisciplinary approach, and its diverse and vibrant community of scholars, students and practitioners working at the intersection of human rights and legal pluralism. CHRLP is a focal point for innovative legal and interdisciplinary research, dialogue and outreach on issues of human rights and legal pluralism. The Centre’s mission is to provide students, professors and the wider community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with how law impacts upon some of the compelling social problems of our modern era. A key objective of the Centre is to deepen transdisciplinary — 2 collaboration on the complex social, ethical, political and philosophical dimensions of human rights. The current Centre initiative builds upon the human rights legacy and enormous scholarly engagement found in the Universal Declartion of Human Rights. ABOUT THE SERIES The Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) Working Paper Series enables the dissemination of papers by students who have participated in the Centre’s International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP). -

Naming the Witch, Housing the Witch and Living with Witchcraft: an Ethnography of Ordinary Lives in Northern Ghana’S Witch Camps

Naming the Witch, Housing the Witch and Living with Witchcraft: An Ethnography of Ordinary Lives in Northern Ghana’s Witch Camps By Saibu Mutaru Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Social Anthropology) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Ilana van Wyk Co-supervisor: Dr Thomas Cousins December 2019 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own original work, that I am the authorship owner thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2019 Signature: Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In Dagbambaland, northern Ghana, people who were accused and proven to be witches and who risked being harmed were banished by village chiefs and local elders (or fled on their own) to special settlements popularly known to locals as accused women’s (or old women’s) settlements, and to the media and NGO world as “witch camps”. Here, an earth priest and anti- witchcraft specialist, the tindana, ritually removed the dark powers of the morally compromised witch and committed him or her to the protection and necessary sanctions of the ancestral shrine. Post-1990 so-called “witch camps” have attracted much attention from churches, state agencies and NGOs interested in the human rights abuses that supposedly took place in these “camps”. -

Witchcraft Accusations As an "Old Woman's Problem" in Ghana Alexandra Crampton Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Social and Cultural Sciences Faculty Research and Social and Cultural Sciences, Department of Publications 1-1-2013 No Peace in the House: Witchcraft Accusations as an "Old Woman's Problem" in Ghana Alexandra Crampton Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Anthropology & Aging Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 2 (2013): 199-212. DOI. © 2013 Association for Anthropology & Gerontology. Used with permission. ARTICLES No Peace in the House: Witchcraft Accusations as an “Old Woman’s Problem” in Ghana Alexandra Crampton Department of Social and Cultural Sciences Marquette University Abstract In Ghana, older women may be marginalized, abused, and even killed as witches. Media accounts imply this is common practice, mainly through stories of “witches camps” to which the accused may flee. Anthropological literature on aging and on witchcraft, however, suggests that this focus exaggerates and misinterprets the problem. This article presents a literature review and exploratory data on elder advocacy and rights intervention on behalf of accused witches in Ghana to help answer the question of how witchcraft accusations become an older woman’s problem in the context of aging and elder advocacy work. The ineffectiveness of rights based and formal intervention through sponsored education programs and development projects is contrasted with the benefit of informal conflict resolution by family and staff of advocacy organizations. Data are based on ethnographic research in Ghana on a rights based program addressing witchcraft accusations by a national elder advocacy organization and on rights based intervention in three witches camps. Keywords: older women, witchcraft, Ghana, advocacy, human rights, development Introduction Witchcraft beliefs are a part of every day life in Ghana are no national statistics on the scope of this problem, and and a part of aging in Ghana as well. -

Childhood Experiences of Abuse Due to Cultural Superstition and Exclusion: a Story of Survival and the Healing Process Theresa Kashale Scholten University of St

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 2018 Childhood Experiences of Abuse Due to Cultural Superstition and Exclusion: A Story of Survival and the Healing Process Theresa Kashale Scholten University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Kashale Scholten, Theresa, "Childhood Experiences of Abuse Due to Cultural Superstition and Exclusion: A Story of Survival and the Healing Process" (2018). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 131. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/131 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Childhood Experiences of Abuse Due to Cultural Superstition and Exclusion: A Story of Survival and the Healing Process BY THERESA KASHALE-SCHOLTEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE EDUCATION FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS, MINNESOTA ABSTRACT The purpose of this qualitative study was to describe the experiences of children enduring abuse due to their identification as enfant sorcerers and to expose the phenomenon of witch-hunts and abuse through the eyes and experiences of victims. I investigated how adult victims of child abuse survive and make meaning of their experience of cultural exclusion and violence committed against them due to superstitious cultural practices, such as witch-hunts and exorcism. -

INTRODUCTION Witchcraft Violence in Comparative Perspective Y•Z

INTRODUCTION Witchcraft Violence in Comparative Perspective Y•Z On August 23, 2004, a High Court of Justice in Ghana imposed the death penalty on a 39-year-old carpenter for bludgeoning his wife to death (Amanor 1999a; Sah 2004). The sentence followed a protracted court trial and a guilty verdict for a brutal murder that had occurred fi ve years previ- ously. The assailant claimed he killed his wife after she had transmogrifi ed into a lioness during the dead of night, and was about to devour him. In a sworn deposition given to law enforcement authorities, and later affi rmed by the defendant during the criminal trial, the assailant testifi ed that at the time of the murder, he and his thirty-two-year-old wife had been mar- ried for six years and together had a fi ve-year-old daughter. He indicated that some days prior to the murder their daughter fell ill and that he had transported her to a local member of the clergy for spiritual healing. The court learned that while at the cleric’s house the assailant confi ded in the pastor that he had been experiencing petrifying nightmares in which he saw his wife transformed into a hermaphrodite, attempting to kill and can- nibalize him. The priest reportedly off ered him apowdery concoction with instructions to sprinkle the substance in his bedroom for three consecu- tive days. The husband was advised that he would see “wonders” shortly thereafter. He told police that following his administration of the sub- stance, his nightmares became more graphic and intense. -

The Concept of Witchcraft in Ghana

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. RESEARCH REVIEW (NS) VOL. 12, Nos. 1 & 2 (1996) THEY HAVE USED A BROOM TO SWEEP MY WOMB: THE CONCEPT OF WITCHCRAFT IN GHANA Owusu Brempong Introduction Witchcraft is an element of the beliefs which are prevalent in Ghanaian societies. In this paper some of the general characteristics of witches and their activities against human beings will be investigated. The belief in witchcraft is prevalent not only among the rural folks in Ghana, but also in the cities among the western educated; it cuts across all social categories. In their conclusion to African Christianity, George Bond, Walton Johnson and Sheila S. Walker ac- knowledge that traditional beliefs including witchcraft are part of the religious experience of the people in the African Cities. They write: Movement located in more remote areas tend to focus on the traditional concerns of healing and witchcraft eradication, whereas those located closer to urban ar- eas tend to have a broader spectrum of concerns. The issues of healing and witchcraft are, however, often present in the urban movements and, in many instances, such as in the church of the Messiah, may be reinter- preted in terms of the concerns of modem urban life} Witchcraft is more than a cultural thread; it is the warp reinforcing the spiritual fabric of Ghanaian societies. -

Akan Witchcraft and the Concept of Exorcism in the Church of Pentecost

AKAN WITCHCRAFT AND THE CONCEPT OF EXORCISM IN THE CHURCH OF PENTECOST by OPOKU ONYINAH A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham February 2002 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Full Name (surname first) Opoku Onyinah School of Historical Studies/ Theology Akan Witchcraft and the Concept of Exorcism in the Church of Pentecost Doctor of Philosophy Witchcraft and “exorcisms” have dominated African cultures and posed problems for African people. This thesis is a study of the current exorcistic ministry within a Pentecostal church in Ghana with reference to the Akan culture. The general opinion gathered from current anthropological studies on witchcraft is that the ultimate goal of exorcism is to become modernised. However, using interdisciplinary studies with a theological focus, the thesis departs from this, and contends that it is divinatory- consultation or an inquiry into the sacred and the search for meaning that underlies the current “deliverance” ministry, where the focus is to identify and break down the so- called demonic forces by the power of God in order to “deliver” people from their torment. -

Uncanny Objects and the Fear of the Familiar: Hiding from Akan Witches in New York City

Uncanny objects and the fear of the familiar: Hiding from Akan witches in New York City This article examines the cosmology and secret practices of West African traditional priests in New York City in preventing the spread of witchcraft, an evil invisible spirit transmitted between female members of the Akan matrilineage. Explored is an uncanny dynamic as everyday habitus becomes increasingly strange in the world of a young Ghanaian woman in the Bronx, who has become petrified of insinuations of witchcraft from close family members. In trying to hide the young woman from infection by her fellow witches, Akan priests attempt to ‘capture’ her habits and everyday routines, calling upon the iconic magic of New York City in order to ‘misplace’ familiarity within the anonymity of Manhattan. In this process, the transmission of the witch’s spirit to the intended victim is disturbed as the victim’s life and things are moved. Nowhere to be found, the witch shifts her attention to other victims. Keywords Akan witchcraft, uncanny, New York, objects Introduction: Akan witchcraft and the uncanny object Amma, a young Ghanaian woman, aged twenty-one, lived in the West Bronx, New York City, the poorest congressional district in the United States (ICPH, 2014). She was part of a highly visible diaspora of West Africans who have migrated to the United States since the early 1980s and especially over the last fifteen years. Unconcerned about her long-term employment possibilities and future in New York, she had, like many young Ghanaian migrants, a high-school diploma and gained work at various times as a receptionist and also as a store worker. -

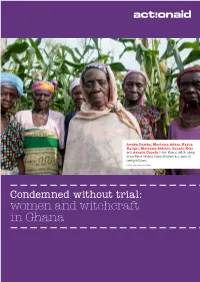

Women and Witchcraft in Ghana

We’re ActionAid. We’re people who are dedicated to ending the extreme poverty that kills 28 children every minute of every day. We’re a charity and much more. We’re a partnership between people in poor countries and people in rich countries – all working together to end poverty for good. ActionAid UK Hamlyn House Macdonald Road London N19 5PG United Kingdom Awaba Damba, Mariama Adam, Kasua Telephone Kaligri, Mariama Iddrisu, Sanatu Kojo +44 (0)20 7561 7561 and Ashetu Chonfo (l-r) in Kukuo witch camp Facsimile +44 (0)20 7272 0899 in northern Ghana, have all been accused of Email being witches. [email protected] PHOTO: JANe HAHN/AcTIONAID Website www.actionaid.org.uk International Secretariat Johannesburg Asia Region Office Bangkok Africa Region Office CondemnedNairobi without trial: Americas Region Office Rio De Janeiro Europewomen Office and witchcraft Brussels Ifin you require Ghanathis publication in a large print format please contact us on +44 (0)1460 23 8000. All publications are available to download from our website: actionaid.org.uk Printed on recycled paper by a printer holding internationally recognised environmental accreditation ISO 14001. Please remember to recycle this item when you have finished with it. ActionAid is a registered charity no. 274467. 3 Condemned without trial Executive summary In northern Ghana hundreds of women accused of witchcraft by relatives or members of their community are living in ‘witch camps’ after fleeing or being banished from their homes. The camps, which are home to around 800 women and 500 children, offer poor living conditions and little hope of a normal life. -

Witchcraft, Violence and Mediation in Africa: a Comparative Study of Ghana and Cameroon Shelagh Roxburgh Thesis Submitted To

Witchcraft, Violence and Mediation in Africa: A comparative study of Ghana and Cameroon Shelagh Roxburgh Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Political Studies School of Political Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa ©Shelagh Roxburgh, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction: Waking from the Fantasy of Western Reality 1 Chapter 2 – Theories of the Unknown: The usual work of political science and witchcraft 38 Chapter 3 – Into the World of Witches: A method for studying witchcraft 69 Chapter 4 – Witches on the Road to Power: Witchcraft and the state in Africa 97 Chapter 5 – Empowering Witches and the West: NGOs and Witchcraft Intervention 131 Chapter 6 – Prayer is the Only Protection: Religious Organizations and Witchcraft 163 Chapter 7 – Accessing the Invisible World: The shared origins of Traditional Authorities and Witches 186 Chapter 8 – Flying by Night: Looking for Answers in the Dark 207 References 217 ii Abstract This thesis explores the question of how witchcraft-related violence may be best addressed through the discipline of political science. This comparative analysis seeks to investigate the effectiveness of four actors mediation efforts: the state, religious organizations, NGOs and traditional authorities. Based on an extensive inter-disciplinary literature review and fieldwork conducted in Ghana and Cameroon, this thesis views witchcraft as a form of power and through this analysis presents two inter-related conclusions. The first conclusions argues that no actor is currently able to successfully address witchcraft-related violence or reduce the sense of spiritual insecurity which is associated with violence due to logical constraints. -

The Modernity of Witchcraft in the Ghanaian Online Setting

The Modernity of Witchcraft in the Ghanaian Online Setting A Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) By Idris Simon Riahi Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS) University of Bayreuth, Germany Supervisor: Professor Dr. Ulrich Berner 18.09.17 ii Erklärung Ich versichere hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit ohne unzulässige Hilfe Dritter und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe; die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Darüber hinaus versichere ich, dass ich weder bisher Hilfe von gewerblichen Promotionsberatern bzw. –vermittlern in Anspruch genommen habe, noch künftig in Anspruch nehmen werde. Die Arbeit wurde bisher weder im Inland noch im Ausland in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form einer anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und ist auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Bielefeld, 09/18/17 Idris Simon Riahi iii Widmung Ich widme diese Arbeit meinen geliebten Eltern. Ihr habt nie mehr, aber auch nie weniger verlangt, als dass ich meine Wege selbst wähle und gehe. Dabei wart Ihr immer meine stillen Begleiter. iv Danksagungen Vielen Personen gilt Dank für ihre stille oder offene Unterstützung zur Erstellung dieser Dissertation. Ich denke besonders an meine Lehrer, meine Familie und meine Freunde, die das Entstehen dieser Arbeit begleitet haben. Zuallererst danke ich Prof. Dr. Ulrich Berner, der mich das Thema frei wählen und gestalten ließ. Prof. Berners Ratschläge und seine treffenden Einschätzungen waren wegweisend und haben mir immer wieder geholfen, die konkreten Stärken in meinem Thema zu finden, herauszuarbeiten und schließlich gebündelt darzustellen. -

Magic, Explanations, and Evil: on the Origins and Design of Witches and Sorcerers

Magic, explanations, and evil: On the origins and design of witches and sorcerers Manvir Singh Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University 6 August 2018 Abstract In nearly every documented society, people believe that some misfortunes are attributable to malicious group mates employing magic or supernatural powers. Here I report cross-cultural patterns in these beliefs and propose a theory to explain them. Using the newly-created Survey of Mystical Harm, I show that several conceptions of evil, mystical practitioners recur around the world, including sorcerers (who use learned spells), possessors of the evil eye (who transmit injury through their stares and words), and witches (who possess superpowers, pose existential threats, and engage in morally abhorrent acts). I argue that these beliefs develop from three cultural selective processes – a selection for effective-seeming magic, a selection for plausible explanations of impactful misfortune, and a selection for demonizing myths that justify mistreatment. Separately, these selective schemes produce traditions as diverse as shamanism, conspiracy theories, and campaigns against heretics – but around the world, they jointly give rise to the odious and feared witch. I use the tripartite theory to explain the forms of beliefs in mystical harm and outline ten predictions for how shifting conditions should affect those conceptions. Societally-corrosive beliefs can persist when they are intuitively appealing or serve some believers’ agendas. ON THE ORIGINS AND DESIGN OF WITCHES AND SORCERERS “I fear them more than anything else,” said Don Talayesva about witches.1 By then, the Hopi man suspected his grandmother, grandfather, and in-laws of using dark magic against him.