Gas and Flatulence Prevention Diet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Diseases

General signs and symptoms of abdominal diseases Dr. Förhécz Zsolt Semmelweis University 3rd Department of Internal Medicine Faculty of Medicine, 3rd Year 2018/2019 1st Semester • For descriptive purposes, the abdomen is divided by imaginary lines crossing at the umbilicus, forming the right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower quadrants. • Another system divides the abdomen into nine sections. Terms for three of them are commonly used: epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric, or suprapubic Common or Concerning Symptoms • Indigestion or anorexia • Nausea, vomiting, or hematemesis • Abdominal pain • Dysphagia and/or odynophagia • Change in bowel function • Constipation or diarrhea • Jaundice “How is your appetite?” • Anorexia, nausea, vomiting in many gastrointestinal disorders; and – also in pregnancy, – diabetic ketoacidosis, – adrenal insufficiency, – hypercalcemia, – uremia, – liver disease, – emotional states, – adverse drug reactions – Induced but without nausea in anorexia/ bulimia. • Anorexia is a loss or lack of appetite. • Some patients may not actually vomit but raise esophageal or gastric contents in the absence of nausea or retching, called regurgitation. – in esophageal narrowing from stricture or cancer; also with incompetent gastroesophageal sphincter • Ask about any vomitus or regurgitated material and inspect it yourself if possible!!!! – What color is it? – What does the vomitus smell like? – How much has there been? – Ask specifically if it contains any blood and try to determine how much? • Fecal odor – in small bowel obstruction – or gastrocolic fistula • Gastric juice is clear or mucoid. Small amounts of yellowish or greenish bile are common and have no special significance. • Brownish or blackish vomitus with a “coffee- grounds” appearance suggests blood altered by gastric acid. -

2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

MEDICAL POLICY – 2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome BCBSA Ref. Policy: 2.04.26 Effective Date: July 1, 2021 RELATED MEDICAL POLICIES: Last Revised: June 8, 2021 None Replaces: N/A Select a hyperlink below to be directed to that section. POLICY CRITERIA | DOCUMENTATION REQUIREMENTS | CODING RELATED INFORMATION | EVIDENCE REVIEW | REFERENCES | HISTORY ∞ Clicking this icon returns you to the hyperlinks menu above. Introduction Intestinal dysbiosis is a condition that occurs when the microorganisms in the digestive tract are out of balance. This condition is believed to cause diseases of the digestive tract, including poor nutrient absorption, overgrowth of certain bacteria, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Symptoms of these digestive problems are similar and may include: abdominal pain, excess gas, bloating, and changes in bowel movements (constipation or diarrhea, or both). One method of diagnosing digestive disorders is by testing a fecal sample. Using fecal analysis to diagnose intestinal dysbiosis, IBS, malabsorption, or small intestinal overgrowth of bacteria is unproven (investigational). More studies are needed to see if this testing improves health outcomes. Note: The Introduction section is for your general knowledge and is not to be taken as policy coverage criteria. The rest of the policy uses specific words and concepts familiar to medical professionals. It is intended for providers. A provider can be a person, such as a doctor, nurse, psychologist, or dentist. A provider also can be a place where medical care is given, like a hospital, clinic, or lab. This policy informs them about when a service may be covered. -

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults NAMIRAH JAMSHED, MD; ZONE-EN LEE, MD; and KEVIN W

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults NAMIRAH JAMSHED, MD; ZONE-EN LEE, MD; and KEVIN W. OLDEN, MD Washington Hospital Center, Washington, District of Columbia Constipation is traditionally defined as three or fewer bowel movements per week. Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age, inactivity, low caloric intake, low-fiber diet, low income, low educational level, and taking a large number of medications. Chronic constipa- tion is classified as functional (primary) or secondary. Functional constipation can be divided into normal transit, slow transit, or outlet constipation. Possible causes of secondary chronic constipation include medication use, as well as medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism or irritable bowel syndrome. Frail older patients may present with nonspecific symptoms of constipation, such as delirium, anorexia, and functional decline. The evaluation of constipa- tion includes a history and physical examination to rule out alarm signs and symptoms. These include evidence of bleeding, unintended weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, acute onset constipation in older patients, and rectal prolapse. Patients with one or more alarm signs or symptoms require prompt evaluation. Referral to a subspecialist for additional evaluation and diagnostic testing may be warranted. (Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):299-306. Copyright © 2011 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ▲ Patient information: onstipation is one of the most of 1,028 young adults, 52 percent defined A patient education common chronic gastrointes- constipation as straining, 44 percent as hard handout on constipation is 1,2 available at http://family tinal disorders in adults. In a stools, 32 percent as infrequent stools, and doctor.org/037.xml. -

Today's Topic: Bloating

Issue 1; August 2017 Dr. Rajiv Sharma attended medical school at Daya- nand Medical College, Punjab, India. He received his Undernourished, intelligence Internal Medicine training from Loma Linda Univer- sity, Loma Linda, California and received his Gastro- becomes like the bloated belly enterology Fellowship training from University of Rochester, Rochester, New York. Dr. Sharma trained of a starving child: swollen, under the mentorship of Dr. Richard G. Farmer, who is world renowned for his work on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. filled with nothing the body Rajiv Sharma, MD Dr. Sharma’s special interests include GERD, NERD, can use.” Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Crohn’s & Ulcerative Colitis), IBS, Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis, Gastro- intestinal Malignancies and Familial Cancer Syn- - Andrea Dworkin dromes. In an effort to share his extensive knowledge with the public, Dr. Sharma re- leased his first book, Pursuit of Gut Happiness: A Guide for Using Probiotics to Inside this issue Achieve Optimal Health, in 2014. In Dr. Sharma’s free time, he enjoys medical writing, watching movies, exercis- Differential Diagnosis 2 ing and spending time with his family. He believes in “whole person care” and the effect of mind, body and spirit on “wellness”. He has a special interest in nu- trition, exercise and healthy eating. He prides himself on being a “fact doctor” as Signs of a More Serious 2 he backs his opinions and works with solid scientific research while aiming to deliver a simple and clear message. Problem Lab Workup 2 Non-Pathological Bloating 2 Today’s Topic: Bloating Bloating may seem an odd topic to choose for our first newsletter. -

An Osteopathic Approach to Reduction of Readmissions for Neonatal Jaundice

Osteopathic Family Physician (2013) 5, 17–23 REVIEW ARTICLE An osteopathic approach to reduction of readmissions for neonatal jaundice Rachel Click, DO,a Julie Dahl-Smith, DO,a Lindsay Fowler, DO,a Jacqueline DuBose, MD,a Margi Deneau-Saxton, RN, CCCE, CIMI, CLC, CPD,b Jennifer Herbert, MDc From aGeorgia Health Sciences University, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Family Medicine, GA; bGeorgia Health System, OB Labor and Delivery, GA; and cUniversity Primary Care, Evans, GA. KEYWORDS: Jaundice is a potentially life-threatening condition that continues to affect at-risk newborns, accounting Breastfeeding; for continued hospital readmissions. As family physicians, we should be cognizant of neonates who may Jaundice; be at risk for jaundice, including those with pathologic jaundice as well as newborns of breastfeeding Prevention; mothers, and ensure sufficient intervention is taken to help prevent further elevations in bilirubin levels. Hyperbilirubinemia; Interventions are likely to include evaluation for sepsis, education regarding feeding frequencies for both Neonatal massage breast- and bottle-fed neonates, reviewing maternal and hematologic risk factors for neonatal jaundice, and considering inborn errors of metabolism. An additional measure family physicians may consider is that of neonatal massage for those with elevated bilirubin levels. Neonatal massage, though not widely used, has been proven to promote excess bilirubin excretion, thus decreasing length of hospital stay; all the while, providing an intervention that allows parents to take an active role. r 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction morbidity rate with bilirubin 4 20 mg/dL. “It has been estimated that the risk of kernicterus in infants with total Jaundice is a product of excess bilirubin (a product of serum bilirubin (TSB) greater than 30 mg/dL is about 1 in broken down red blood cells), which manifests as a 7 infants”.1 Less serious complications of hyperbilirubine- yellowing of the skin and eyes. -

Travelers' Diarrhea

Travelers’ Diarrhea What is it and who gets it? Travelers’ diarrhea (TD) is the most common illness affecting travelers. Each year between 20%-50% of international travelers, an estimated 10 million persons, develop diarrhea. The onset of TD usually occurs within the first week of travel but may occur at any time while traveling and even after returning home. The primary source of infection is ingestion of fecally contaminated food or water. You can get TD whenever you travel from countries with a high level of hygiene to countries that have a low level of hygiene. Poor sanitation, the presence of stool in the environment, and the absence of safe restaurant practices lead to widespread risk of diarrhea from eating a wide variety of foods in restaurants, and elsewhere. Your destination is the most important determinant of risk. Developing countries in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia are considered high risk. Most countries in Southern Europe and a few Caribbean islands are deemed intermediate risk. Low risk areas include the United States, Canada, Northern Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and several of the Caribbean islands. Anyone can get TD, but persons at particular high-risk include young adults , immunosuppressed persons, persons with inflammatory-bowel disease or diabetes, and persons taking H-2 blockers or antacids. Attack rates are similar for men and women. TD is caused by bacteria, protozoa or viruses that are ingested by eating contaminated food or beverages. For short-term travelers in most areas, bacteria are the cause of the majority of diarrhea episodes. What are common symptoms of travelers’ diarrhea? Most TD cases begin abruptly. -

INFORMED CARING JAUNDICE Neonatal Jaundice BILIARY

1 INFORMED CARING Situations with Adults and Children with Gallbladder, Liver and Pancreatic Disorders 2 JAUNDICE ä Does NOT mean hepatitis ä Increased breakdown of RBCs ä Altered bilirubin breakdown ä Impeded flow through liver or bile duct ä First seen in sclera, then skin 3 Neonatal Jaundice ä Not liver failure ä RBC breakdown ä Phototherapy 4 BILIARY ATRESIA ä Jaundice 2-3 weeks after birth ä Easy bruising ä Stools putty like ä Tea colored urine ä Abdominal/organ distension 5 4 F’s of Gallbladder ä Fair ä Fat X size of person X amount in diet ä Fertile X BCP X Multiparity ä Forty 6 Cholelithiasis ä Calculi within the duct or gallbladder ä Severe colicky, cramp-like pain X radiates to shoulder blade X Murphy's sign ä Cholecystitis: inflammation X Can be caused by trauma, fasting, TPN or abdominal surgery 7 Diagnostic Studies ä Ultrasound of abdomen 1 X not for the obese ä HIDA scan X nuclear medicine ä Cholangiograms X endoscopic X transvenous X intraoperative 8 Post-op Care ä High abdominal incision X respiratory compromise ä T-tube X patients need to know how to empty it X may clamp it prior to removal X caution not dislodged with movements ä NO Morphine X spasms of sphincter of Oddi 9 Post-op Nutrition ä Limited fat in diet X can have rapid transit times ä Potential fat soluble vitamin deficit X A, D, E and K ä Weight loss diet 10 LIVER FAILURE ä Cirrhosis ä Drug toxicity X acetaminophen, anesthetics, HCTZ, chemotherapy ä Infection ä Cancer ä ETOH is single most linked cause 11 LIVER FAILURE S/S ä Don’t show up until 80-90% failed -

Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21

20 Osteopathic Family Physician (2019) 20 - 25 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 11, No. 2 | March/April, 2019 Gennaro, Larsen Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21 Review ARTICLE to escape. This mechanism prevents the stomach from becoming IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS) Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating damaged by excessive dilation.2 IBS is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered with OMT Treatment Options Many patients with GERD report increased belching. Transient bowel habits. It is the most commonly diagnosed GI disorder lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation is the major and accounts for about 30% of all GI referrals.7 Criteria for IBS is recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the Carly Gennaro, DO1; Helaine Larsen, DO1 mechanism for both belching and GERD. Recent studies have shown that the number of belches is related to the number of last three months associated with at least two of the following: times someone swallows air. These studies have concluded that 1) association with defecation, 2) change in stool frequency, 1 Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, West Islip, NY patients with GERD swallow more air in response to heartburn and 3) change in stool form. Diagnosis should be made using these therefore belch more frequently.3 There is no specific treatment clinical criteria and limited testing. Common symptoms are for belching in GERD patients, so for now, physicians continue to abdominal pain, bloating, alternating diarrhea and constipation, treat GERD with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2 and pain relief after defecation. Pain can be present anywhere receptor antagonists with the goal of suppressing heartburn and in the abdomen, but the lower abdomen is the most common KEYWORDS: ABSTRACT: Intestinal gas production is a normal physiologic progress. -

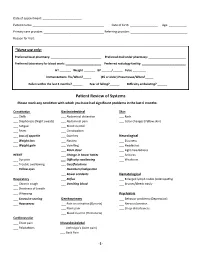

Patient Review of Systems Please Mark Any Condition with Which You Have Had Significant Problems in the Last 6 Months

Date of appointment: ________________________ Patient name: ____________________________________________ Date of birth: _________________ Age: ___________ Primary care provider: _____________________________________ Referring provider: ___________________________________ Reason for Visit: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ *Nurse use only: Preferred local pharmacy: _______________________________ Preferred mail order pharmacy: _______________________ Preferred laboratory for blood work: ______________________ Preferred radiology facility: ___________________________ HT _______ Weight _______ BP ______/______ Pulse ________ Immunizations: Flu/When?_____ (65 or older) Pneumovax/When?_____ Fallen within the last 3 months? ______ Fear of falling?______ Difficulty ambulating? ______ Patient Review of Systems Please mark any condition with which you have had significant problems in the last 6 months: Constitution Gastrointestinal Skin ___ Chills ___ Abdominal distention ___ Rash ___ Diaphoresis (Night sweats) ___ Abdominal pain ___ Color changes (Yellow skin) ___ Fatigue ___ Blood in stool ___ Fever ___ Constipation ___ Loss of appetite ___ Diarrhea Neurological ___ Weight loss ___ Nausea ___ Dizziness ___ Weight gain ___ Vomiting ___ Headaches ___ Black stool ___ Light-headedness HEENT ___ Change in bowel habits ___ Seizures ___ Eye pain ___ Difficulty swallowing ___ Weakness ___ Trouble swallowing ___ Gas/flatulence ___ Yellow eyes ___ Heartburn/indigestion ___ Bowel accidents Hematological -

Traveller's Diarrhoea (TD) Is the Commonest Health

Diarrhoea • THEME Traveller's diarrhoea BACKGROUND There has been little if any Traveller's diarrhoea (TD) is the commonest health change in the incidence of traveller's diarrhoea problem facing travellers to less developed countries over the past 20 years. of the world. It is costly to both the traveller (time lost) and the host country (eg. cancelled activities). OBJECTIVE This article aims to provide a basic understanding on why travellers are more likely to Definition experience diarrhoea during travel. Classic TD is described as three or more loose bowel DISCUSSION In a 20 minute pretravel actions with at least one of the following accompanying consultation time is precious, and providing symptoms: nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps or information on traveller's diarrhoea often has pain, fever or blood in the stools. Lesser degrees a low priority over prescribing the necessary vaccinations and discussing antimalarials. (moderate or mild) of TD are also described. Severity is Bob Kass, Travellers do not follow the rules of eating and usually defined by the number of bowel actions per 24 drinking safely, and diarrhoea is common. 'What hour period (severe >6). According to the World Health MBBS, MRCP (UK), MScMCH, Organisation, symptoms lasting less than 14 days may to do in the event of illness' is an important DCH, FAFPHM, consideration. Presumptive treatment should be defined as 'acute diarrhoea', and those lasting more is a consultant, be offered to all travellers whose itinerary and than 14 days 'persistent diarrhoea'.1 International Public activities put them at risk. Between 30 and 50% of travellers will be affected Health Medicine, Rede-Health in a 2 week overseas stay, with approximately 12% International. -

Abdominal Complaints

Abdominal Complaints EMD CE May 2016 Silver Cross EMSS Introduction to Abdominal Emergencies • Abdominopelvic pain has many causes, and can be an indication of serious underlying conditions. • Abdominal pain results from these mechanisms: – Stretching – Inflammation – Ischemia (insufficient blood supply to an organ) • Care includes managing life threats, making the patient comfortable, and transport. What’s Acute Abdomen? Acute Abdomen – Caused by irritation of the abdominal wall – May result from infection or the presence of blood in the abdominal cavity – Pain can be referred to other parts of the body. – The abdomen may feel as hard as a board. – Patients may have nausea and vomiting, fever, and diarrhea as well as pain. Some patients will vomit or pass blood because they are bleeding from the esophagus or stomach. Ask about bowel and bladder problems • Vomiting/diarrhea/constipation – Associated with many acute abdominal disorders – Can cause abdominal pain – Dehydration serious enough to cause shock may occur. Have they been eating and drinking normally? • Urination problems often accompany kidney or bladder problems. Abdominal/Pelvic Pain Considerations: Onset? What were they doing when it started? Provocation/Palliation? Anything make it worse or better? What have they done for pain relief? Quality? (Type of pain) Ache, cramping or sharp pain? Radiation/Region/Referred? Where is the pain? Does it travel anywhere? Severity? 1-10 Scale rating Time? How long has it been going on? Ever happen before? Acute Abdomen • The abdominal cavity extends from the diaphragm to the pelvis and contains organs of digestion, reproduction and excretion. • The parietal peritoneum lines the abdominal cavity, and the visceral peritoneum is in contact with the organs. -

Type 2 Diabetes SCAN Formulary Drugs

Pharmacologic Agents for Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes SCAN Formulary Drugs 2020 2021 Risk for Dosing & Drug- Drug Medication Formulary Formulary Adverse Drug Reactions Administration Interactions Tier UM Tier UM * Biguanides 500 – 850 mg Nausea/ vomiting, GI upset, metallic taste, metformin tabs 1 1 QD - TID diarrhea, flatulence, lactic acidosis (rare) metformin er Neutral 500 – 2000 mg Nausea/ vomiting, GI upset, diarrhea, flatulence, uncoated tabs 1 1 daily lactic acidosis 500 mg & 750 mg Sulfonylureas Dizziness, headache, hypoglycemia, nausea, glimepiride 1 1 1 – 8 mg daily weight gain 2.5 – 20 mg Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, diarrhea, glipizide 1 1 daily Moderate hypoglycemia, nausea, weight gain Asthenia, headache, dizziness, rash, nausea, glipizide er 1 1 5 – 20 mg daily hypoglycemia, weight gain glipizide / 2.5 / 500 mg Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, nausea, 1 1 Moderate metformin tabs BID flatulence, hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis Thiazolidinediones & Thiazolidinedione Combination Agents 15 – 45 mg Anemia, edema, weight gain, headache, myalgia, pioglitazone 1 1 daily bone fracture, heart failure 15 / 500 mg – pioglitazone / Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, nausea, 2 2 45 / 1500mg metformin Neutral flatulence, hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis daily 15 / 500 mg – pioglitazone / Anemia, edema, weight gain, headache, myalgia, 2 [QL] 2 [QL] 45 / 2550 mg glimepiride dizziness, hypoglycemia, nausea daily R. Brower and N. Nguyen rev. 11/2012; R. Brower rev. 11/2013, 9/2014, 11/2015; D. Yoon rev 8/2016, 11/2016, 8/2017; K.