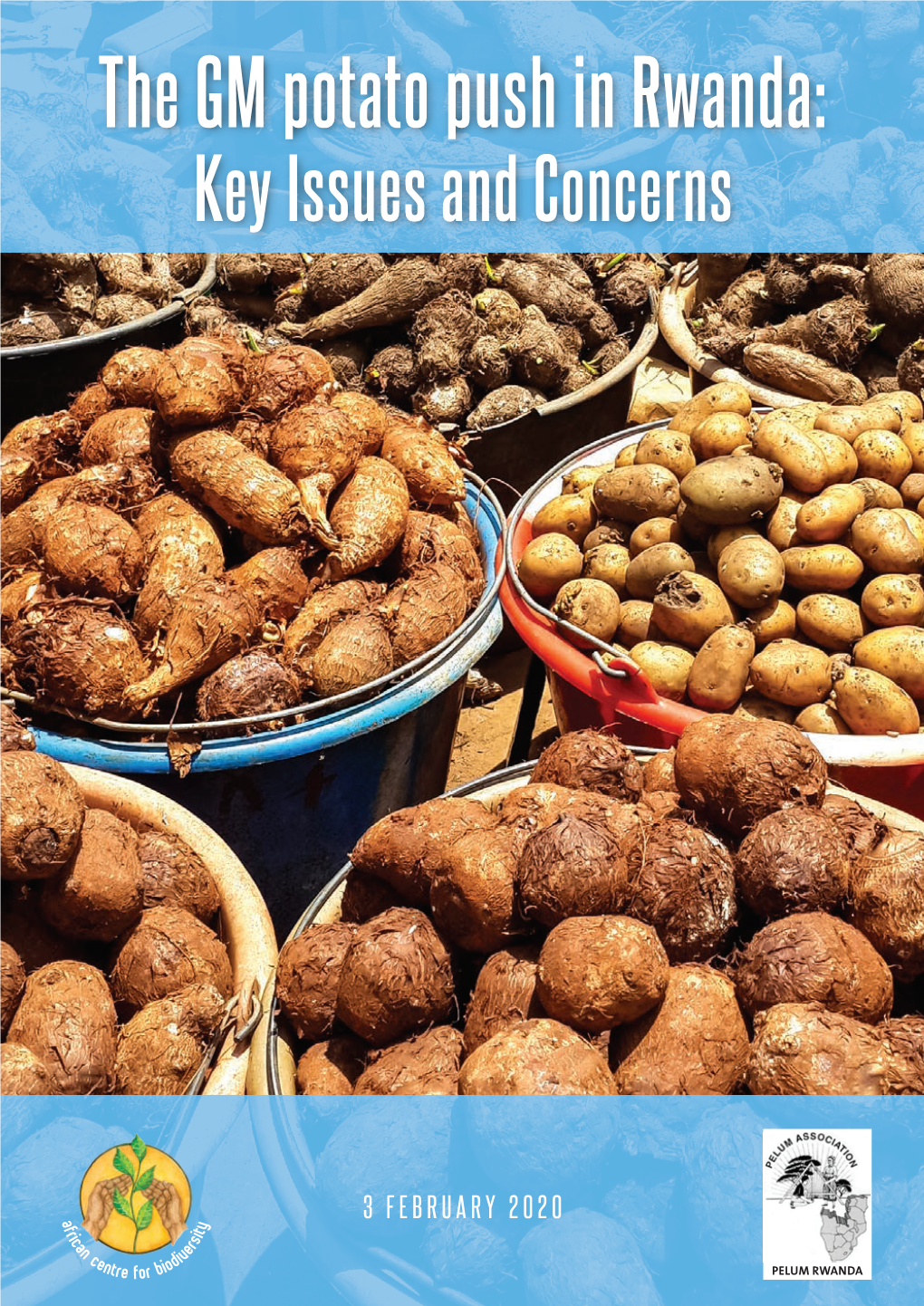

The GM Potato Push in Rwanda: Key Issues and Concerns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTER-ANNUAL TEMPERATURE VARIABILITY and PROJECTIONS on ITS IRISH POTATOES PRODUCTION in RWANDA (Case Study: MUSANZE and NYABIHU

INTER-ANNUAL TEMPERATURE VARIABILITY AND PROJECTIONS ON ITS IRISH POTATOES PRODUCTION IN RWANDA (Case study: MUSANZE and NYABIHU Districts) RUKUNDO Emmanuel (MSc) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the award of the degree of Master of Science in the School of Science and Technology of University of Rwanda Supervisor: Prof. BONFILS Safari NOVEMBER 2018 i DECLARATION I Rukundo Emmanuel declare that, this thesis is my original work and has not been Presented/submitted for a degree in any other University or any other award. Rukundo Emmanuel Department of Physics Signature................................................. Date......................................... I confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the Student under my supervision. Prof. Bonfils Safari Department of Physics University of Rwanda Signature............................................ Date......................................... ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my parents who educated and taught me that there is no other way leading to the richness except to converge to school together with obeying God. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Foremost, this thesis is a result of the contribution of many peoples to whom I express my deepest gratitude. I am forever indebted to all of you who made my master’s journey possible. To my supervisor Prof Bonfils, who has been a source of knowledge, challenge and encouragement during the course of my studies, your guidance and valuable criticism were keys for the elaboration of this thesis and for my improvement as a researcher. Your great dedication to your students is impressive. I thank you for your close attention to detail on those many drafts you read. To my lecturer including Dr Gasore Jimmy, who helped me in every step of this study and whose enthusiasm for science have made these masters a true adventure for me. -

FAO Rwanda Newsletter, December 2020

FAO Rwanda Newsletter December 2020 — Issue #2 FAO/Teopista Mutesi FAO/Teopista Sustaining food systems with rural women in agriculture potential risk in the region. There are many more interesting stories from the people we work in the field in this newsletter. We congratulate our FAO-Rwanda colleague, Jeanne d’Arc who was recognized by the FAO Director General as a committed staff to the Organization, and welcome to new staff who joined the office during the difficult times. I move my vote of thanks to the FAO-Rwanda team, FAO regional and headquarters offices, our partners, service providers and the farmers for your commtiment, together we have made it! I look forward to working with you, and FAO/Teopista Mutesi FAO/Teopista more partners in the coming year. Message from the FAO Representative I wish you a happy holiday season, and blessings in the New Year 2021! Dear Reader, Enjoy reading. We are almost at the end of 2020! For the most part of the year, the world has been battling with COVID-19 pandemic. Gualbert Gbehounou, We got familiar with the words like, build back better, FAO Representative lockdown, teleworking or ‘working from here’ and washing hands every now and then, etc. HIGHLIGHTS Empowering rural women to become entrepreneurs. It has been equally a challenging period working in the Vegetable farmers in rural Rwanda are building back field, yet, colleagues at FAO-Rwanda have been resilient better. and doubled efforts to improve the livelihoods of the Increasing organic farmers in Rwanda. farmers in Rwanda. Immediately after the COVID-19 Clarifying gender equality in the gender-based induced lockdown was lifted on the country, we distributed violence fight. -

Republic of Rwanda

i REPUBLIC OF RWANDA WESTERN PROVINCE NYABIHU DISTRICT P.O. Box 125 RUHENGERI Website: www.nyabihu.gov.rw E-mail: [email protected] DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2013-2018) Nyabihu, June 2013 i FOREWORD The second District development Plan of Nyabihu is the decentralized operational medium-term plan for Nyabihu to translate the nation Economic development and poverty reduction Vision 2020. Nyabihu DDP builds on the EDPRS 2 that is bringing emphasis of Economic transformation with rapid growth of real GDP growth of 11.5. It (DDP Nyabihu) covers the period of the EDPRS 2 ranging 2013/14-2017/18. The EDPRS 2 whose overarching goal to “Accelerating progress to middle income status and better quality of life for all Rwandans” has got four key thematic areas: economic transformation, Rural development, Youth and employment, and Accountable governance. However, DDP plan is consultatively developed with many expectations to transform our district whereby predominantly its population is farmers with limited ha portion over the five years starting from 2013 up to 2018. Indeed inside it consist of district priorities aimed at enabling economic transformation. For the next five years emphasis will be on economic transformation with key priorities namely: developing Mukamira Industrial Economic Zone to increase high potential for tourism; ensure efficient and effective & affordable infrastructure ( water, energy and IT), accelerated human settlement habitat (IMIDUGUDU); Increase agricultural product (Inga no, Urutoki, and Irish Potatoes) and livestock productivity, Empowering youth in professional, technical competences and job creation (Off farming activities), develop and increase formal private sector. In addition some cross cuttings will be mainstreamed such as Gender & Family, Capacity Building, Environment, Climate change and Disaster Management. -

RWANDA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions June 2012

RWANDA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions June 2012 MAP OF REVISED LIVELIHOOD ZONES IN RWANDA FEWS NET Washington FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. The content of this report does not [email protected] necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for International www.fews.net Development or the United States Government. RWANDA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Revised Livelihood Zones in Rwanda............................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Rural Livelihood Zones in Rwanda ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Lake Kivu Coffee & Food Crops (Zone 1) ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Zone 1: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................................................. -

Introduction Generale

The 5th ICEED, KIGALI-RWANDA-UNILAK AUGUST, 2018 EAJST Special Vol.8 Issue2, 2018 by Maniriho A. et al P28-45 Effects of Fertilizer use on Potato Production in Western Rwanda Authors:Aristide Maniriho*1 ,Cyprien Habyarimana2 *Corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] 1School of Economics, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda 2School of Economics, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda Abstract This study analysed the effects of fertilizer use on potato production in Kabatwa Sector, Nyabihu District, in Western Rwanda. Data were collected among 100 potato growers randomly selected in Kabatwa sector for the season 2014B. A well structured questionnaire was distributed in August 2014, and required information about the respondent’s identification, fertilizer use, potato production and related constraints. The paired-samples T-test was used for data analysis. The results show that fertilizers have positive effects on potato output. The results from the paired-samples t-test show that the difference between the average crop production after and the average crop production before the adoption of fertilizers in the study area (1,155 kgs) is statistically different from zero following that the corresponding p-value (labelled Sig. 2-tailed) is smaller than 0.05. Accordingly, there has been a statistically significant difference between the potato output level comparing before and after fertilizer use in the study area. It was recommended that the Government should enhance fertilizer accessibility through credit facility to farmers, facilitate access to proximity extension services and encourage farmers to group into cooperatives. Key words: fertilizer use, potato production, paired-samples T-test, Rwanda JEL Classification Codes: D60; O13; O18; Q13; R20 28 The 5th ICEED, KIGALI-RWANDA-UNILAK AUGUST, 2018 EAJST Special Vol.8 Issue2, 2018 by Maniriho A. -

The Impact of Land Degradation on Agricultural Productivity in Nyabihu District-Rwanda, a Case Study of Rugera Sector Mr

International Journal of Environmental & Agriculture Research (IJOEAR) ISSN:[2454-1850] [Vol-6, Issue-7, July- 2020] The Impact of Land Degradation on Agricultural Productivity in Nyabihu District-Rwanda, A Case Study of Rugera Sector Mr. Emmanuel Rushema1, Dr. Abias Maniragaba2, Mr. Levy Ndihokubwayo3, Mr Luc Cimusa Kulimushi4 Department of environmental economics and natural resource management; faculty of environmental studies; University of Lay Adventists of Kigali, P. O. Box: 6392 Kigali- Rwanda Abstract— This study looked at the impact of land degradation on agricultural productivity in Nyabihu district. Specific objectives were to assess the factors influencing land degradation in Nyabihu district, Rugera sector, the vulnerability level of land degradation and propose suitable land management conservation strategies. Geographical Information system (GIS) and Remote sensing data were used for the assessment of factors influencing land degradation, where Land cover (classified) maps were produced based on data extracted from google earth and cultivated slope was computed based on the Digital elevation model (DEM) of 2018 downloaded from earthexplorer.usgs.gov. GIS vulnerability assessment and classification method was used to assess level of vulnerability to soil degradation and land slide. To propose suitable land management conservation strategies practical Tools on Soil and Water Conservation measures alongside with W4GR matrix of soil and water conservation measures documents were consulted. The data collected were analyzed using ArcGIS 10.4software, and Excel; the results were presented using maps, bar graphs and tables. Based on two main factors (slope and soil depth) a conservation map and matrix were developed with proposed options of restoration and conservation of land degraded. -

CBD Fifth National Report

REPUBLIC OF RWANDA FIFTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY March, 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The preparation of the Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is one of the key obligations of the Parties to the Convention. It is an important communication tool for biodiversity planning, providing the analysis and monitoring necessary to inform decisions on the implementation of the convention. This report is structured in three major parts: i. An update of biodiversity status, trends, and threats and implications for human well-being; ii. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP), its implementation and the mainstreaming of biodiversity in different sectors; and iii. An analysis on how national actions are contributing to 2020 CBD Aichi Targets, and to the relevant 2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). PART 1: AN UPDATE OF BIODIVERSITY STATUS, TRENDS, AND THREATS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN WELL-BEING This section comprises four main sub-sections including statements on the importance of biodiversity for the country; the main threats to biodiversity both in natural and agro-ecosystems; the major changes that have taken place in the status and trends of biodiversity; and the impacts of the changes in biodiversity for ecosystem services and the socio-economic and cultural implications of these impacts. Importance of biodiversity for the country’s economy: it has been demonstrated that the country’s economic prosperity depends on how natural capital is maintained. Now, in Rwanda, there is a good understanding of linkages between biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being, though the value of biodiversity is not yet reflected in country broader policies and incentive structures. -

Aciar 'Trees for Food Security'

ACIAR ‘TREES FOR FOOD SECURITY’ PROJECT THE EXTENSION SYSTEM IN RWANDA: A FOCUS ON BUGESERA, RUBAVU AND NYABIHU DISTRICTS Evelyne Kiptot, Ruth Kinuthia and Amini Mutaganda DECEMBER 2013 CONTRIBUTORS Evelyne Kiptot World Agroforestry Centre P.0 Box 30677-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Ruth Kinuthia World Agroforestry Centre P.0 Box 30677-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Amini Mutaganda Rwanda Agriculture Board P. O Box 5016 Kigali-Rwanda ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As part of the baseline survey for the ACIAR Trees for Food Security Project, a literature review and key informants interviews were undertaken in June 2013 to understand the status of the extension system in Rwanda. Visits were made to RAB in Kigali, Eastern provincial headquarters, districts, sectors and cells whereby key informant interviews were undertaken to understand the extension systems in Rwanda. In addition, various NGOs and extension service providers were also visited. The major areas of focus were: Extension technologies disseminated to farmers Community engagement Capacity and efficiency Linkage with other institutions Commercialization and marketing Local innovation Extension in Rwanda is under two ministries: MINAGRI (Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock) which sets policies and guidelines and MINALOC (Ministry of Local Government) which implements the policies. RAB (Rwanda Agriculture Board) is an institution under MINAGRI whose mission is to develop agriculture and animal husbandry through the use of modern methods in crop and animal production, research, agricultural extension, education and training of farmers in new technologies. At RAB there is the Deputy Director General who is in charge of extension, and works with officers in other fields, agronomy, livestock and forestry. The lowest level of extension is at the village (Umudugudu) level, here there are farmer promoters who coordinate extension activities. -

Organic Law No 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 Determining The

Year 44 Special Issue of 31st December 2005 OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA Nº 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 Organic Law determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda. Annex I of Organic Law n° 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda relating to boundaries of Provinces and the City of Kigali. Annex II of Organic Law n° 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda relating to number and boundaries of Districts. Annex III of Organic Law n° 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda relating to structure of Provinces/Kigali City and Districts. 1 ORGANIC LAW Nº 29/2005 OF 31/12/2005 DETERMINING THE ADMINISTRATIVE ENTITIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA We, KAGAME Paul, President of the Republic; THE PARLIAMENT HAS ADOPTED AND WE SANCTION, PROMULGATE THE FOLLOWING ORGANIC LAW AND ORDER IT BE PUBLISHED IN THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA THE PARLIAMENT: The Chamber of Deputies, in its session of December 2, 2005; The Senate, in its session of December 20, 2005; Given the Constitution of the Republic of Rwanda of June 4, 2003, as amended to date, especially in its articles 3, 62, 88, 90, 92, 93, 95, 108, 118, 121, 167 and 201; Having reviewed law n° 47/2000 of December 19, 2000 amending law of April 15, 1963 concerning the administration of the Republic of Rwanda as amended and complemented to date; ADOPTS: CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL PROVISIONS Article one: This organic law determines the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda and establishes the number, boundaries and their structure. -

Technical Efficiency and Its Determinants on Irish Potato Farming Among Small Holder Farmers in Trans-Nzoia County-Kenya

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume III, Issue V, May 2019|ISSN 2454-6186 Technical Efficiency and Its Determinants on Irish Potato Farming among Small Holder Farmers in Trans-Nzoia County-Kenya Augustine Wafula Barasa1, Paul Okelo Odwori2, Josephine Barasa3, Steven Ochieng1 1Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, University of Eldoret, P. O. Box 1125-30100, Eldoret, Kenya, 2Department of Economics, University of Eldoret, P. O. Box 1125-30100, Eldoret, Kenya. 3Department of Soil Science, University of Eldoret, P. O. Box 1125-30100, Eldoret, Kenya. Abstract: - Increased pressure on land brought about by result of institutional failures, market constraints and limited increased population in the highlands of Western Kenya such as transfer and adoption of improved technologies by Trans Nzoia County has led to increased land fragmentation and smallholders farmers hence stalling agricultural productivity forced farmers to diversify their crops to alternative value chains and growth (Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Mareny, 2015).This that are more profitable and take less time to mature. An low productivity has resulted in stagnated rural incomes, example of an innovation being promoted is the adoption of Irish potato as an alternative to maize farming. However, in fuelling a vicious cycle of poverty and food insecurity among determining farm productivity, onlyfew studies have looked at the local communities (Valbuena, Groot, Mukalama, Gérard, the efficiency of the Irish potato production. This has prompted B., & Tittonell, 2015).Thus, farmers need to diversify and this study to determine the technical efficiencies of smallholder seek for alternative crops that require less time to mature in farmers’ Irish potato production in the study area by providing order to achieve the expected high yields. -

Quarterly Report

INZIRA NZIZA ACTIVITY Award No.: AID-696-F-17-00001 Quarterly Report Quarter 1I: 1 January -31 March 2019 Submitted by Never Again Rwanda Contact Person:Page Dr. 1 ofJoseph 45 Nkurunziza Executive Director Email:[email protected] Page 2 of 45 Contents 1. Project Description/Introduction ........................................................................................................ 4 2. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Activity implementation progress/ Accomplishments ................................................................. 7 3.1. Meet your Member of Parliament (MYMP) in Nyabihu District .............................................. 7 3.1. Radio and TV programs on youth participation in decision making processes and development ................................................................................................................................................... 9 3.2. Roundtable discussion in Gisagara District ................................................................................ 13 3.3. District exchange meetings in Nyamagabe and Nyabihu Districts ................................... 16 3.4. Joint trainings for youth and local leaders in Nyabihu and Ngororero Districts .............. 19 3.5. Public Forum Debate Competitions in Nyabihu and Ngororero Districts ......................... 32 3.7. The Face to Face Portal ................................................................................................................. -

RWANDA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions June 2012

RWANDA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions June 2012 MAP OF REVISED LIVELIHOOD ZONES IN RWANDA FEWS NET Washington FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. The content of this report does not [email protected] necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for International www.fews.net Development or the United States Government. RWANDA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Revised Livelihood Zones in Rwanda............................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Rural Livelihood Zones in Rwanda ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Lake Kivu Coffee & Food Crops (Zone 1) ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Zone 1: Seasonal calendar ..................................................................................................................................................