Species Concepts James Mallet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

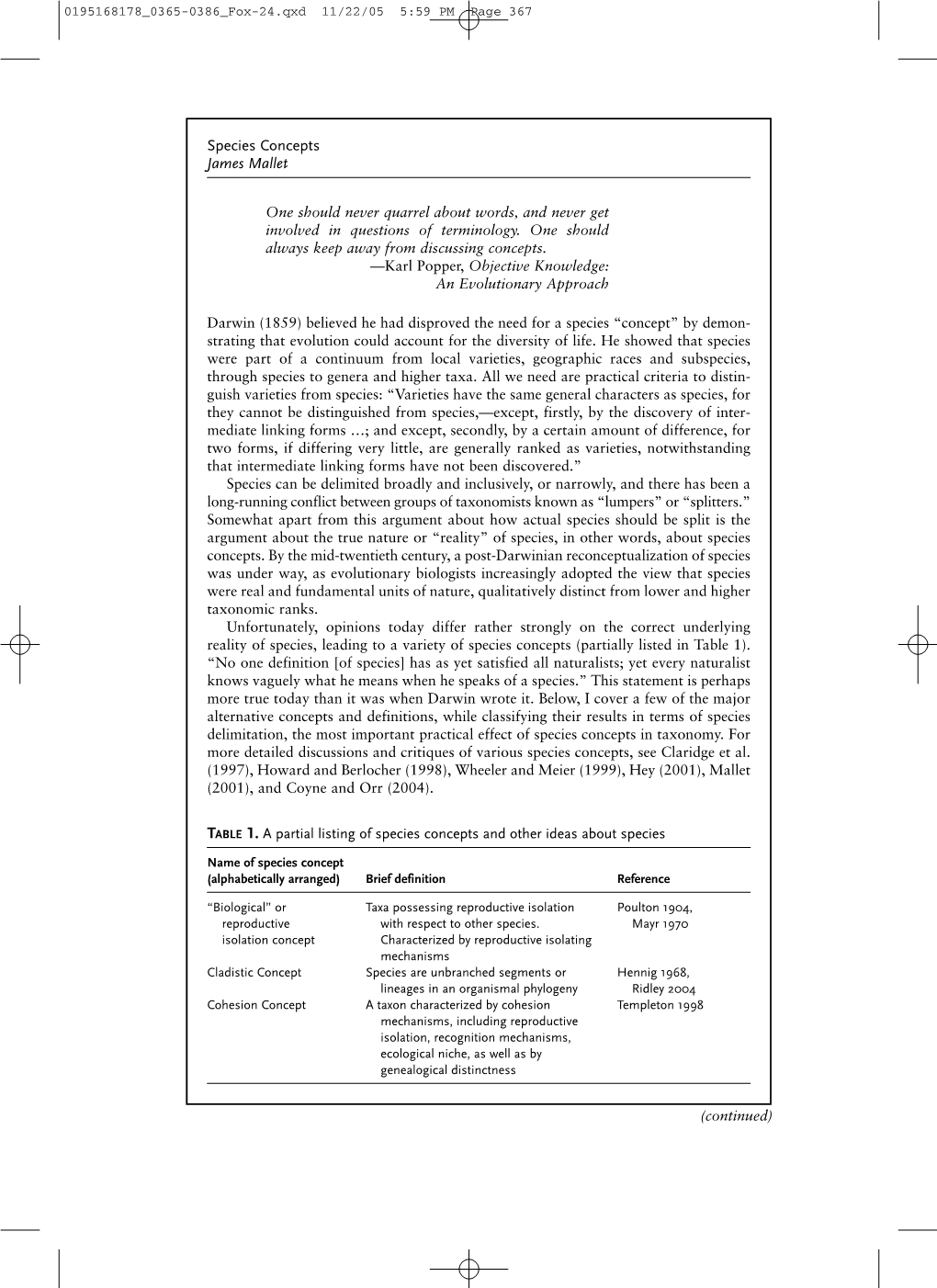

Recommended publications

-

The Taxonomy of Primates in the Laboratory Context

P0800261_01 7/14/05 8:00 AM Page 3 C HAPTER 1 The Taxonomy of Primates T HE T in the Laboratory Context AXONOMY OF P Colin Groves RIMATES School of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 3 What are species? D Taxonomy: EFINITION OF THE The biological Organizing nature species concept Taxonomy means classifying organisms. It is nowadays commonly used as a synonym for systematics, though Disagreement as to what precisely constitutes a species P strictly speaking systematics is a much broader sphere is to be expected, given that the concept serves so many RIMATE of interest – interrelationships, and biodiversity. At the functions (Vane-Wright, 1992). We may be interested basis of taxonomy lies that much-debated concept, the in classification as such, or in the evolutionary implica- species. tions of species; in the theory of species, or in simply M ODEL Because there is so much misunderstanding about how to recognize them; or in their reproductive, phys- what a species is, it is necessary to give some space to iological, or husbandry status. discussion of the concept. The importance of what we Most non-specialists probably have some vague mean by the word “species” goes way beyond taxonomy idea that species are defined by not interbreeding with as such: it affects such diverse fields as genetics, biogeog- each other; usually, that hybrids between different species raphy, population biology, ecology, ethology, and bio- are sterile, or that they are incapable of hybridizing at diversity; in an era in which threats to the natural all. Such an impression ultimately derives from the def- world and its biodiversity are accelerating, it affects inition by Mayr (1940), whereby species are “groups of conservation strategies (Rojas, 1992). -

Species Concepts and the Evolutionary Paradigm in Modern Nematology

JOURNAL OF NEMATOLOGY VOLUME 30 MARCH 1998 NUMBER 1 Journal of Nematology 30 (1) :1-21. 1998. © The Society of Nematologists 1998. Species Concepts and the Evolutionary Paradigm in Modern Nematology BYRON J. ADAMS 1 Abstract: Given the task of recovering and representing evolutionary history, nematode taxonomists can choose from among several species concepts. All species concepts have theoretical and (or) opera- tional inconsistencies that can result in failure to accurately recover and represent species. This failure not only obfuscates nematode taxonomy but hinders other research programs in hematology that are dependent upon a phylogenetically correct taxonomy, such as biodiversity, biogeography, cospeciation, coevolution, and adaptation. Three types of systematic errors inherent in different species concepts and their potential effects on these research programs are presented. These errors include overestimating and underestimating the number of species (type I and II error, respectively) and misrepresenting their phylogenetic relationships (type III error). For research programs in hematology that utilize recovered evolutionary history, type II and III errors are the most serious. Linnean, biological, evolutionary, and phylogenefic species concepts are evaluated based on their sensitivity to systematic error. Linnean and biologica[ species concepts are more prone to serious systematic error than evolutionary or phylogenetic concepts. As an alternative to the current paradigm, an amalgamation of evolutionary and phylogenetic species concepts is advocated, along with a set of discovery operations designed to minimize the risk of making systematic errors. Examples of these operations are applied to species and isolates of Heterorhab- ditis. Key words: adaptation, biodiversity, biogeography, coevolufion, comparative method, cospeciation, evolution, nematode, philosophy, species concepts, systematics, taxonomy. -

Reproductive Isolation of Two Sympatric Louseworts, Pedicularis

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4066© 2006 The Linnean Society of London? 2006 90? 3748 Original Article REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION IN SYMPATRIC LOUSEWORTS C.-F. YANG ET AL . Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 90, 37–48. With 4 figures Reproductive isolation of two sympatric louseworts, Pedicularis rhinanthoides and Pedicularis longiflora (Orobanchaceae): how does the same pollinator type avoid interspecific pollen transfer? CHUN-FENG YANG, ROBERT W. GITURU† and YOU-HAO GUO* College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, People’s Republic of China Received 11 April 2005; accepted for publication 1 March 2006 To study the isolation mechanism of two commonly intermingled louseworts, Pedicularis rhinanthoides and Pedic- ularis longiflora, pollination biology in three mixed populations with the two species was investigated during a 3- year project. The results indicated that higher flowering density could help to enhance pollinator activity, and thus increase reproductive output. Bumblebees are the exclusive pollinator for the two louseworts and are essential for their reproductive success. Reproductive isolation between the two species is achieved by a combination of pre- and postzygotic isolation mechanisms. Although both species are pollinated by bumblebees, the present study indicates they successfully avoid interspecific pollen transfer due to floral isolation. Mechanical isolation is achieved by the stigma in the two species picking up pollen from different parts of the pollinator’s body, whereas ethological isolation occurs due to flower constancy. Additionally, strong postzygotic isolation was demonstrated by non seed set after arti- ficial cross-pollination even with successful pollen tube growth. We describe the hitherto unreported role of variation in the tightness and direction of the twist of the corolla beak in maintaining mechanical isolation between Pedicu- laris species. -

Behavioural Mechanisms of Reproductive Isolation Between Two Hybridizing Dung Fly Species

Animal Behaviour 132 (2017) 155e166 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Behavioural mechanisms of reproductive isolation between two hybridizing dung fly species * Athene Giesen , Wolf U. Blanckenhorn, Martin A. Schafer€ Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland article info Characterization of the phenotypic differentiation and genetic basis of traits that can contribute to Article history: reproductive isolation is an important avenue to understand the mechanisms of speciation. We quan- Received 29 November 2016 tified the degree of prezygotic isolation and geographical variation in mating behaviour among four Initial acceptance 26 January 2017 populations of Sepsis neocynipsea that occur in allopatry, parapatry or sympatry with four populations of Final acceptance 21 June 2017 its sister species Sepsis cynipsea. To obtain insights into the quantitative genetic basis and the role of selection against hybrid phenotypes we also investigated mating behaviour of F1 hybrid offspring and MS. number: 16-01039R corresponding backcrosses with the parental populations. Our study documents successful hybridization under laboratory conditions, with low copulation frequencies in heterospecific pairings but higher fre- Keywords: quencies in pairings of F1 hybrids signifying hybrid vigour. Analyses of F1 offspring and their parental biogeography backcrosses provided little evidence for sexual selection against hybrids. -

10 What Is a Species? Investigation • 3–4 C L a S S S E S S I O N S

10 What Is a Species? investigation • 3–4 c l a s s s e s s i o n s OVERVIEW MatERIals and adVanCE PREPaRatIOn In this activity students learn about the biological species For the teacher concept in defining species and how it provides information transparency of Scoring Guide: GROUP INTERACTION (GI) about where new species are in the process of separation transparency of Scoring Guide: UNDERSTANDING from closely related species. Students then investigate the CONCEPTS (UC) factors that lead to reproductive isolation of species. For each group of four students set of 14 Species Pairs Cards KEy COntEnt set of 8 Reproductive Barrier Cards 1. Species evolve over time. The millions of species that live chart paper* (optional) on the earth today are related by descent from common markers* (optional) ancestors. For each student 2. Taxa are classified in a hierarchy of groups and sub- Student Sheet 10.1, “Supporting a Scientific Argument” groups based on genealogical relationships. (optional) 3. The broad patterns of behavior exhibited by animals Scoring Guide: GROUP INTERACTION (GI) (optional) have evolved by natural selection as a result of reproduc- Scoring Guide: UNDERSTANDING CONCEPTS (UC) tive success. (optional) 4. Scientists have found that the original definition of spe- *Not supplied in kit cies as groups of organisms with similar morphology Decide in advance if you will hand out Student Sheet does not reflect underlying evolutionary processes. 10.1,“Supporting a Scientific Argument,” or have students 5. The biological species concept defines a species as a pop- record this information in their science notebooks. -

Speciation in Geographical Setting

Speciation Speciation 2019 2019 The degree of reproductive isolation Substantial variation exists in among geographical sets of species - anagenesis populations within an actively 1859 1859 evolving species complex is often Achillea - yarrow tested by crossing experiments — as in the tidy tips of California 100K bp 100K bp back in time back in time back Rubus parviforus K = 4 mean population assignment 2 mya 2 mya ID CO WI_Door 5 mya BC_Hixton BC_MtRob WI_BruleS 5 mya BC_McLeod CA_Klamath MI_Windigo WA_Cascade WA_BridgeCr SD_BlackHills OR_Willamette MI_Drummond Speciation Speciation 2019 Reproductive isolation will ultimately stop all Although simple in concept, the recognition of species and thus the definition genetic connections among sets of populations of what are species have been controversial — more than likely due to the – cladogenesis or speciation continuum nature of the pattern resulting from the process of speciation 1859 Example: mechanical isolation via floral shape changes and pollinators between two parapatric species of California Salvia (sage) 100K bp back in time back 2 mya S. mellifera 5 mya Salvia apiana 1 Speciation Speciation Although simple in concept, the recognition of species and thus the definition Animal examples of speciation often show of what are species have been controversial — more than likely due to the clear reproductive barriers - hence zoologists continuum nature of the pattern resulting from the process of speciation preference (as opposed to botanists) for the Reproductive isolating Biological -

THE IMPACT of POLYPLOIDY on GENETIC STRUCTURE and REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION in the GENUS LEUCANTHEMUM Mill. (COMPOSITAE, ANTHEMIDEAE)

THE IMPACT OF POLYPLOIDY ON GENETIC STRUCTURE AND REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION IN THE GENUS LEUCANTHEMUM Mill. (COMPOSITAE, ANTHEMIDEAE) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Fakultät für Biologie und vorklinische Medizin der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Roland Greiner aus Regensburg im Dezember 2011 Das Promotionsgesuch wurde eingereicht am: Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: Prof. Dr. Christoph Oberprieler Unterschrift: Evolution is a change from an indefinite, incoherent, homogeneity to a definite, coherent, heterogeneity, through continuous differentiations and integrations. Herbert Spencer Evolution is a change from a no-howish, untalkaboutable, all-alikeness by continous sticktogetheration and somethingelsification. William James Table of Contents Table of Contents..........................................................................................................I List of Tables...............................................................................................................III Table of Figures...........................................................................................................V Abstract.......................................................................................................................1 General Introduction...................................................................................................2 Types of Polyploidy..................................................................................................3 -

Allopatric Speciation

Lecture 21 Speciation “These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species — that mystery of mysteries”. C. Darwin – The Origin What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. • these barriers may act to prevent fertilization – this is prezygotic isolation. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. • these barriers may act to prevent fertilization – this is prezygotic isolation. • may involve changes in location or timing of breeding, or courtship. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. • these barriers may act to prevent fertilization – this is prezygotic isolation. • may involve changes in location or timing of breeding, or courtship. • barriers also occur if hybrids are inviable or sterile – this is postzygotic isolation. Modes of Speciation Modes of Speciation 1. Allopatric speciation 2. Peripatric speciation 3. Parapatric speciation 4. Sympatric speciation Modes of Speciation 1. Allopatric speciation 2. Peripatric speciation 3. Parapatric speciation 4. Sympatric speciation Modes of Speciation 1. Allopatric speciation Allopatric Speciation ‘‘The phenomenon of disjunction, or complete geographic isolation, is of considerable interest because it is almost universally believed to be a fundamental requirement for speciation.’’ Endler (1977) Modes of Speciation 1. -

Is the Biological Species Concept Showing Its Age? Mohamed A.F

Research Update TRENDS in Ecology & Evolution Vol.17 No.4 April 2002 153 Research News Is the biological species concept showing its age? Mohamed A.F. Noor A recent paper by Chung-I Wu in the Journal not been attained. Hence, such a strict and whether Wu’s proposed revision has of Evolutionary Biology questions the value definition would not match the intuition any advantages. Most of those who of the popular biological species concept of most biologists. Second, speciation responded on these issues were not (BSC) and offers an alternative ‘genic’ is usually driven by natural or sexual favorable to Wu’s proposal. concept based on possessing ‘loci of selection causing functional divergence. Wu presents examples in which the differential adaptation.’ Wu suggests that However, the BSC does not delineate the BSC delineates taxa as species that would recent empirical results from genetic studies evolutionary forces that cause divergence. not attain this designation under his genic of speciation necessitate this revision. As such, the BSC considers reproductively definition. For example, he notes that Several prominent evolutionary biologists isolated units to be species, even if taxa infected with different strains of responded in the same issue, many noting differential adaptation is not apparent. Wolbachia (hence preventing gene excitement over the recent empirical results, Wu proposes what he calls a ‘genic view exchange through cytoplasmic few agreeing with an abandonment of the of the process of speciation’. He suggests incompatibility) would be defined as BSC, and none wholeheartedly embracing that the point in divergence at which species by the BSC. Is this species the new genic concept. -

Sexual Selection, Speciation and Constraints on Geographical Range Overlap in Birds Christopher Cooney

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations Biology 5-16-2017 Sexual selection, speciation and constraints on geographical range overlap in birds Christopher Cooney Joseph A. Tobias Jason T. Weir Carlos A. Botero Washington University in St. Louis, [email protected] Nathalie Seddon Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bio_facpubs Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biology Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cooney, Christopher; Tobias, Joseph A.; Weir, Jason T.; Botero, Carlos A.; and Seddon, Nathalie, "Sexual selection, speciation and constraints on geographical range overlap in birds" (2017). Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations. 139. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bio_facpubs/139 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Sexual selection, speciation, and constraints on geographical 2 range overlap in birds 3 4 Christopher R. Cooney1,2*, Joseph A. Tobias1,3, Jason T. Weir4, Carlos A. Botero5 & 5 Nathalie Seddon1 6 7 1Edward Grey Institute, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, 8 Oxford OX1 3PS, UK. 9 2Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, 10 Sheffield S10 2TN, UK. 11 3Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park, Buckhurst Road, 12 Ascot, Berkshire, SL5 7PY, UK. 13 4Department Ecology and Evolution and Department of Biological Sciences, University of 14 Toronto Scarborough, Toronto, ON M1C 1A4, Canada. -

VIEW Open Access Busting Myths About “Species” Charles H Pence

Pence Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:21 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/21 BOOK REVIEW Open Access Busting myths about “species” Charles H Pence Keywords: Species; Essentialism; Aristotle; Plato; Ernst Mayr; History of biology Book details “Species” from Plato to Darwin Wilkins, John S. With regard to the development of the concept of spe- Species: A History of the Idea cies before Darwin, Wilkins rightly notes that there is an Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009. accepted, standard narrative of this history, constructed, xiv + 288 pp., index, ISBN 9780520260856. as he deftly shows, by biologists during the New Synthesis (around 1958, in fact; p. xi). The “received view” goes something like this. Taking a combination of Platonist es- Species sentialism and Aristotelian logic as a basis, the “species A History of the Idea, by John S. Wilkins. Berkeley, CA: concept” of Linnaeus and all others before Darwin holds University of California Press, 2009. Pp. xiv + 288, index. that species are permanent, eternal, fixed objects consist- H/b $31.95. ing of a set of essential or typical properties, deviations It is a claim often repeated, and reinforced by the peri- from which can at best be monstrous. This is the bogey- odic publication of hefty monographs on the subject man which Mayr labeled “typological thinking” (Mayr (Coyne and Orr 2004), that there is a “species problem” 1959), and, as the story goes, one of Darwin’sgreatestac- in evolutionary biology. Ernst Mayr, in his 1942 book, complishments was its overthrow and replacement by wrote it into the ground floor of the New Synthesis. -

Species & Speciation

Species & Speciation http://malawicichlids.com/ 1 4 “In short, we shall have to treat species in the same manner as those naturalists treat genera, who admit that genera are merely artificial combinations made for convenience. This may not be a cheering prospect; but we shall at least be free from the vain search for the undiscovered and undiscoverable essence of the term species.” Darwin 1859 2 5 Folk Concept Microevolution Macroevolution - of populations - taxonomic diversity - experimental - paleontology - anagenesis - cladogenesis • Reproductive compatibility • Discontinuity 3 6 Species = L.”kind” Reproductive Isolation prezygotic • extrinsic • mate discrimination • gametic incompatibility postzygotic hybrid - • inviability • sterility Raven Crow • breakdown 7 10 Freq. (kHz) Ph. variolosus (Fy) Time (ms) B. obliqua (Fy) P. inanis (F) Donelson et al, unpubl. 8 11 Cryptic Biological Species Concept (BSC) species Species are groups of actually, or potentially, interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups. Mayr, 1942 Chrysoperla (lace wings) 9 12 a a a Problems • Limited domain of application • Inapplicable in practice Morph R ! Molecular R = G x C Bluegill sunfish 13 16 Problems Problems • Limited domain of • Limited domain of application application • Inapplicable in practice • Breeding experiments often inconclusive Bluegill sunfish 14 17 Problems • Limited domain of application • Inapplicable in practice • Breeding experiments often inconclusive • Groups which don’t co- occur in time cannot be evaluated Allender et al, PNAS 2003 Bluegill sunfish 15 18 Biological Species Concept (BSC) Alternatives: Species are groups of Biological SC actually, or potentially, Evolutionary/ Phylogenetic SC interbreeding natural Morphological SC populations that are reproductively isolated Recognition SC from other such groups.