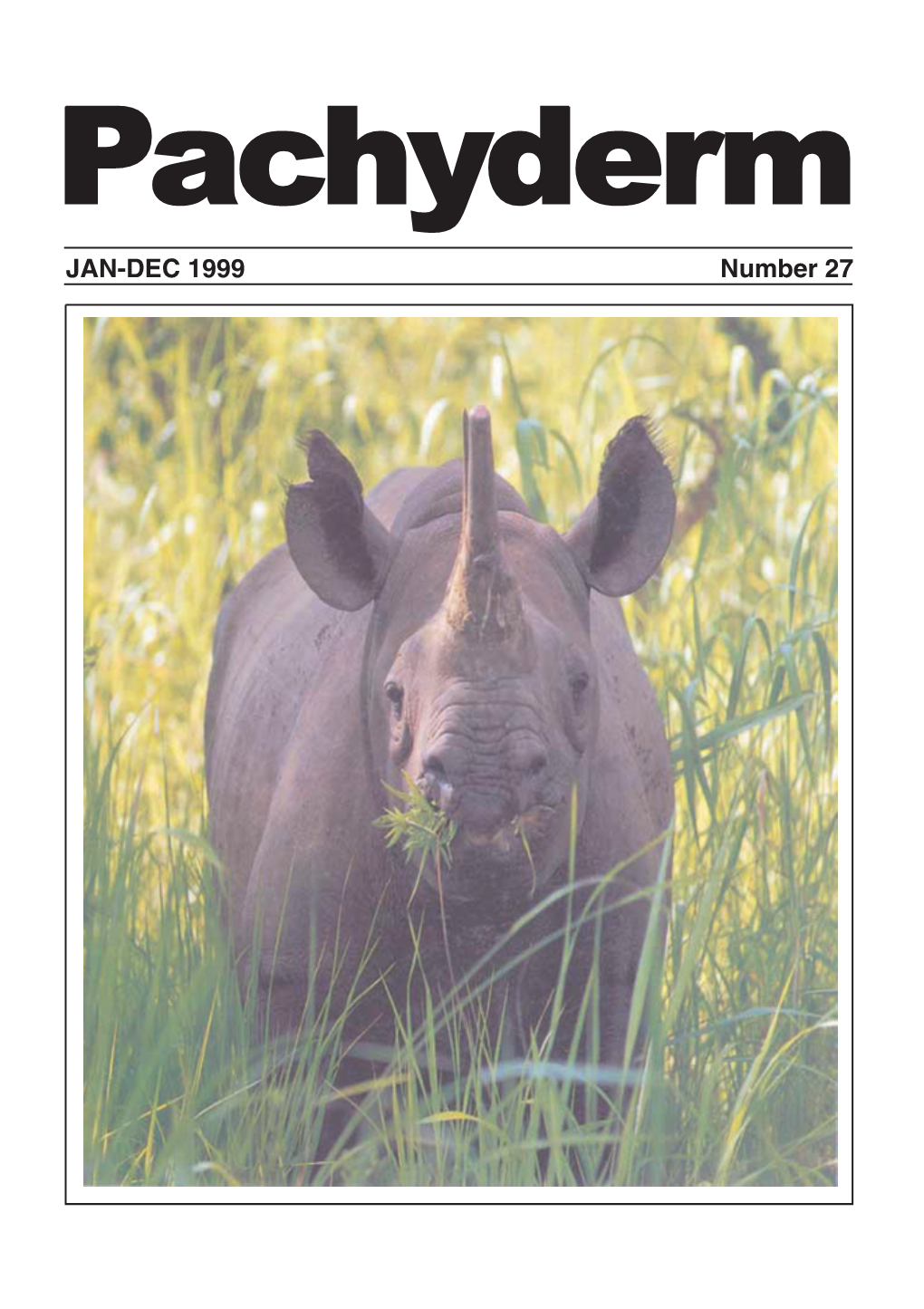

JAN-DEC 1999 Number 27 Editorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equipment Designs

EQUIPMENT DESIGNS Equipment designs and manufacturing drawings are offered for a range of sugar processing equipment as detailed below: x Shredders / Cane Knives – Heavy Duty x Diffusers (Cane and Bagasse) x Juice Heaters x Vapour Heaters (Direct Contact type) x Evaporators x Kestner type x Robert type x Entrainment Separators (Vertical Chevron – Internal & External) x Condensers for Evaporators & Pans (Internal & External) x Batch Vacuum Pans & Stirrers x Continuous Vacuum Pans x Vertical Crystallisers x Massecuite Reheaters x Remelters x Sugar Driers x Sugar Refining Equipment x Direct White Sugar process x Rotary Distribution System x Fluegas Scrubbers x Miscellaneous Equipment Tongaat Hulett Sugar Equipment Designs Shredders / Cane Knives (Heavy Duty) The Tongaat Hulett heavy duty shredder is a robust swing hammer pulveriser. The design incorporates high operating efficiency, low maintenance costs and resistance to damage in service. The patented rotor design gives overlapping coverage of the full shredder width with reversible swing hammers. The shredders have been installed worldwide for the last 25 years and are reliable and proven. The rupturing of the cane cells by the shredder leads to high extractions being obtained in both milling trains and diffusers. Cane & Bagasse Diffusers The Tongaat Hulett Diffuser is a variant of the moving bed diffuser. The basic design is a counter current contactor where juice is pumped (with a high percentage of recycle) onto a moving bed of prepared cane between 1.5 and 1.8 meters deep contained in a vessel approximately 60 meters long and divided into 10 to 14 stages. Typically the diffuser would have a working width between 6 and 12 meters. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Gary Gygax's World Builder

FOR a “GYGAXIAN” FANTASY WORLD THE ESSENTIAL TOOL fOR FANTASY WORLD CREATION! by Gary Gygax & Dan Cross GYGAXIAN FANTASY WORLDS , Vol. II Acknowledgements Authors: Gary Gygax & Dan Cross Cover Artist: Matt Milberger Contributing Authors: Carrie Cross, Michael Leeke, Title Logo: Matt Milberger Jamis Buck, Tommy Rutledge, Josh Hubbell, Stephen Vogel, Luke Johnson & Malcolm Bowers Production: Todd Gray, Stephen Chenault Artists: Dave Zenz, Andy Hopp, & & Davis Chenault Mark Allen Dan Cross: Special thanks to my lovely wife Carrie Cross for the Complete Herbalist lists, John Troy for his valuable suggestions and additions to the D20 material, and to Randall & Debbie Petras for their contributions to the “human descriptors” lists. And a very special thanks to Richard Cross for teaching his son how to write. Troll Lord Games, L.L.C. Or on the Web at PO Box 251171 http://www.trolllord.com Little Rock, AR 72225 [email protected] This book is published and distributed by Troll Lord Games, L.LC. All text in this book, other than this title page and page 180 concerning the Open Game License, is Copyright © 2004 Trigee Enterprises Company. All other artwork, illustration, maps, and trade dress is Copyright © 2004 Troll Lord Games, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. Lejendary Adventure, the Lejendary Adventure logo, and Gary Gygax’s World Builder are Trademarks of Trigee Enterprises Company. All Rights Reserved. Troll Lord Games and the Troll Lord Games logo are Trademarks of Troll Lord Games, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. ‘D20 System’ and the ‘D20 System’ logo are Trademarks owned by Wizards of the Coast and are used according to the terms of the D20 System License version 3.0. -

1924Filipinostrike 22.Pdf

• • • • BIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY: JUNZO KOJIRI, retired truck driver Junzo Kojiri, Japanese, was born on May 15, 1901 in Hiroshima, Japan, one of two children of Ryokichi and Iku Kojiri. He grew up in Japan, and immigrated to Hawaii in 1915 to join his father ~ and brother who were already working in Hawaii. When his father returned • to Japan a few years later, Koj:tfi · -decided to st~y _ on Kauai. He was a fi eTCd worker at Makaweli Plantation from 1915-1918,, surveyor rs ~ helper in 1918, and a track layer in Mana from 1919-1921. In 1921 he became a car and taxi driver for Waimea Stable and later continued as a truck driver for Kauai Commercial until his retirement in 1966 . • He transported a carload of police officers to the site of the Hanapepe incident in 1924 and observed the events from his car parked a distance away. 1 6 1 \ ': ,, ~;a~: rf~~i ~gS~~~~~~n~t'\"' ~~di 1S ~~ a~ t ;~;Y m~~~.~i ~~ ~~~ ~~~~~.~ • · HonpaHongwanji church. The KojiriS live in Waimea . • • • • 540 • Tapes No. 5-7-1-78 and 5-8-1-78 ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW • with Mr. Junzo Koj iri (JK) August 17, 1978 • Waimea, Kaua i BY: Chad Taniguchi (CT) • CT: This is an interview with Mr. Junzo Kojiri, in Waimea, and today is August 17. I just wanted to get some information first. You were born in Hiroshima in 1901. What was the date? • JK: What you mean? My birthday? May 15, 1901. CT: Did you have sisters or brothers? JK: I get one brother over here, Kaumakani. -

Weapons Policy

Tulsa City-County Library Policies Weapons Policy This policy is applicable to any customer or guest of TCCL and all regular full-time, probationary, and part- time/temporary TCCL employees. Dangerous weapons, including but not limited to firearms, are a threat to the safety of the customers and employees of TCCL. In addition, possession of dangerous weapons, or replicas or facsimiles of dangerous weapons, disrupts the normal operation of TCCL. Library Buildings and Bookmobiles (updated April, 2019) No person shall carry into a Library building, bookmobile, or any other TCCL property, any dangerous weapon, replicas or facsimiles of dangerous weapons, weapon accessories or ammunition. Additionally, use of any item or instrument by a customer or employee while on any TCCL property (including vehicle parking areas) to harm or threaten to harm to any person is prohibited. A dangerous weapon includes, BUT IS NOT LIMITED TO, a pistol, revolver, shotgun or rifle whether loaded or unloaded or any dagger, bowie knife, dirk knife, switchblade knife, spring-type knife, sword cane, knife having a blade which opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring, or other device in the handle of the knife, blackjack, loaded cane, billy, hand chain, metal knuckles, or any other offensive weapon, whether such weapon be concealed or unconcealed. The use of items not normally considered weapons or dangerous instruments, such as pocket knives or tools, for intimidation or threat of bodily harm shall also be included, as a weapon, in violation of this policy. THE FOREGOING LIST OF "DANGEROUS WEAPONS" IS DESCRIPTIVE AND BY WAY OF EXAMPLE ONLY AND IS NOT TO BE CONSIDERED AN EXCLUSIVE OR LIMITING LIST OF DANGEROUS WEAPONS. -

History of the Philippine Islands Vols 1 and 2 by Antonio De Morga

History of the Philippine Islands Vols 1 and 2 by Antonio de Morga History of the Philippine Islands Vols 1 and 2 by Antonio de Morga This eBook was produced by Jeroen Hellingman MORGA'S PHILIPPINE ISLANDS VOLUME I Of this work five hundred copies are issued separately from "The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898," in fifty-five volumes. HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS From their discovery by Magellan in 1521 to the beginning of the XVII Century; with descriptions of Japan, China and adjacent countries, by Dr. ANTONIO DE MORGA page 1 / 538 and Counsel for the Holy Office of the Inquisition Completely translated into English, edited and annotated by E. H. BLAIR and J. A. ROBERTSON With Facsimiles [Separate publication from "The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898" in which series this appears as volumes 15 and 16.] VOLUME I Cleveland, Ohio The Arthur H. Clark Company 1907 COPYRIGHT 1907 THE ARTUR H. CLARK COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENTS OF VOLUME I [xv of series] Preface page 2 / 538 Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas. Dr. Antonio de Morga; Mexico, 1609 Bibliographical Data Appendix A: Expedition of Thomas Candish Appendix B: Early years of the Dutch in the East Indies ILLUSTRATIONS View of city of Manila; photographic facsimile of engraving in Mallet's Description de l'univers (Paris, 1683), ii, p. 127, from copy in Library of Congress. Title-page of Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, by Dr. Antonio de Morga (Mexico, 1609); photographic facsimile from copy in Lenox Library. Map showing first landing-place of Legazpi in the Philippines; photographic facsimile of original MS. -

Published in the Journal Record October 28, 2015

(Published in the Journal Record October 28, 2015 ) ORDINANCE NO. 25,269 ORDINANCE RELATING TO MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS AND OFFENSES: AMENDING SECTION 30-302, CARRYING WEAPONS GENERALLY; EXCEPTIONS; AMENDING SECTION 30-303, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GATHERINGS; AMENDING SECTION 30-304, CARRYING CONCEALED WEAPONS; AND REPEALING SECTION 30-307, SALE OF SWITCHBLADE KNIFE OR KNIFE WITH LONG BLADE, DECLARING AN EMERGENCY AND PROVIDING AN EFFECTIVE DATE. EMERGENCY ORDINANCE BE IT ORDAINED BY THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF OKLAHOMA CITY: SECTION 1. That Chapter 30, Article X, Sections 30-302, 30-303, 30-304 and 30-305 of the Oklahoma City Municipal Code, 2010, are hereby amended to read as follows: CHAPTER 30 MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS AND OFFENSES * * * ARTICLE X. FIREARMS AND WEAPONS * * * § 30-302. Carrying weapons generally; exceptions. It shall be unlawful for any person to carry upon or about his person, or in his portfolio or purse, any stun gun, dagger, Bowie knife, dirk knife, switchblade knife, spring-type knife, sword cane, knife having a blade which opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring, or other device in the handle of the knife, blackjack, loaded cane, billy, hand chain, metal knuckles, or any other offensive weapon, except as in this article provided. Provided this Article does not regulate the possession of knives and/or guns, except to the extent the City may regulate the illegal discharge of firearms within the City and the illegal transportation of a loaded pistol in a motor vehicle. All other knife and gun matters are regulated by State law. Provided further, that this section shall not prohibit the proper use of guns and knives for hunting, fishing or recreational purposes, nor shall this section be construed to prohibit any use of weapons in a manner otherwise permitted by municipal ordinance or by State law. -

2019 Quality Handles & Tools

Quality Handles & Tools Replacement Handles Family Owned & Complete Tools Operated Specialty Turning Since 1967 2019 Bowman Handles, Inc. P.O. Box 3297 • Batesville, AR 72503 1743 Batesville Blvd. • Batesville, AR 72501 Ph: 1-800-736-0390 • Fax: 870-251-2803 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bowmanhandlesinc.com 2019-1 Website DESCRIPTION PAGE NO DESCRIPTION PAGE NO ACID BRUSH 24 CORN KNIFE 60 ADJUSTABLE WRENCHES 58 COTTON HOE HANDLE 8 ALUMINUM SCOOPS 50 COTTON SEED FORK 43 ASPHALT RAKES 52 COUNTER DUSTER 24 ASSEMBLY WEDGES 17 COUNTER DUSTER 24 AXE EYE MAULS 34 CROSS PEIN HAMMERS 35 AXE SHEATH 32 CRUISER AXE HANLDE 3 AXES 32 CUTTER MATTOCKS 39 BALL PEIN HAMMER HANDLES 14 DECK BRUSH 25 BALL PEIN HAMMERS 37 D-GRIPS 17 BARN SCRAPER 47 DITCH BANK BLADE HANDLES 5 BEAN HOOK 47 DITCH BANK BLADES 55 BERRY HOE HANDLE 8 DOUBLE BIT AXE 32 BERRY HOES 54 DOUBLE BIT AXE HANDLE 3 BLACKSMITH HAMMER HANDLE 14 DRAIN SPADE 48 BOLT CUTTERS 58 DRILL HAMMER HANDLE 14 BORED & CHUCKED HOE HANDLES 7 DRILL HAMMERS 35 BOW RAKE HANDLE 8 DUAL HEAD PRY BAR 57 BOW RAKES 52 DUST MOP 18 BOYS AXE HANDLE 3 ENGINEER HAMMER HANDLE 14 BRACE 31 ENSILAGE FORK 43 BRICK HAMMER HANDLE 14 EPOXY PACK 17 BRICK HAMMERS 35 EYE HOE BLADE 40 BROAD AXE HANDLE 12 EYE HOE HANDLE 8 BROOM HANDLES 18 FENDER WASH BRUSH 26 BROOMS 20 FERRULES 17 BUNGEE CORDS 62 FIBERGLASS SHOVEL HANDLE 9 BUTTER FLY HOE 40 FILE HANDLE 16 BYPASS HAND PRUNERS 56 FLOOR BRUSH / BLACK TAMPICO 27-28 FLOOR BRUSH/HORSEHAIR & PLASTIC CAMP AXE 32 BLEND 28 FLOOR BRUSH/SILVER FLAGGED TIP CAMP AXE HANDLE 4 PLASTIC -

WOODALL PUBLIC SCHOOL Student Handbook

WOODALL PUBLIC SCHOOL Student Handbook 2020 – 2021 www.woodall.k12.ok.us We are Woodall…Some wish for it, WE work for it! 1 Woodall Public Schools 14090 W 835 Road Tahlequah, OK 74464 Woodall Public Schools Telephone Number: (918) 456-1581 District Website: www.woodall.k12.ok.us Administration Ginger Knight, Superintendent Ray Pinney, Principal Jerrod Hood, Director of Operations Kim Kocsis, Counselor Billy Keys, Athletic Director Sally Stanley, Special Ed Director and 504 Compliance Coordinator Board of Education Eddie Molloy Mark Smith Gary Dotson This handbook has been prepared to help you and your parents become better acquainted with your school. It is our desire that you use this handbook to live up to the high ideas and standards of Woodall Public School. This handbook will be used as a guideline for students and staff. It is the responsibility of the student and guardians to carefully read all information and policies included in this handbook. 2 Woodall Public School Ginger Knight, Superintendent Ray Pinney, Principal 14090 West 835 Road Tahlequah, Oklahoma 74464 Telephone (918) 456-1581 Fax (918)456-5015 _____________________________________________________________________________________ August 2020 Dear Parents and Guardians: I am looking forward to the upcoming school year. Woodall is an excellent school with a dedicated faculty and staff. It is a privilege daily, to work with teachers that have great expectations and provide engaging instruction for each student, leading our students to think beyond boundaries and achieve above standards. We will do our best to ensure that our students are safe, comfortable, and challenged academically each day. I encourage you to communicate regularly with the classroom teachers that work daily with your child. -

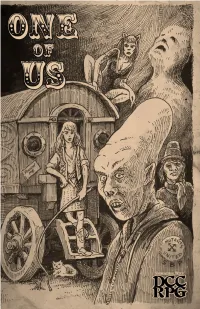

Check out a Preview of One Of

One of us — issue no. 1 — Welcome to the Dustbowl You are no hero... You are a carnie indentured to the mysterious being known as The Madame. In exchange for wondrous powers and “a more perfect self,” The Madame calls upon you to procure magnificent artifacts as you crisscross the dusty and dangerous remains of a once robust and proud land. Cannibal hobos, shadowy cults, and uncouth hecklers will do everything in their power to prevent your caravan from carrying out its mission. Grab your barbells and bullwhips and hop on the caravan to adventure. We accept you! We accept you! One of us! Dungeon Crawl Classics and DCC RPG are trademarks of Goodman Games. For additional information, visit www.goodman-games.com or contact [email protected]. 1 THE BIG MISTAKE It happened a couple of generations ago, and those who were around to see it sure aren’t around anymore. Something to do with big men fighting about big things which led to an explosion way out in the desert. Some- thing evil leaked into the sky and people got sick and the world we knew was gone. Since then, we have been trying to pick up the pieces. These are tough times and we have become simpler people. The luxuries and machines that kept the sweat off our backs lie shattered and rusted under a choking blanket of dust and fallout. That old-time religion sure hasn’t lost its fervor, though. The house of worship that have sprung up are those of vengeful gods. Some of them have become powerful enough to become the law of the rebuilt territo- ries. -

Guidelines for the in Situ Re-Introduction and Translocation of African and Asian Rhinoceros Edited by Richard H Emslie, Rajan Amin & Richard Kock

Guidelines for the in situ Re-introduction and Translocation of African and Asian Rhinoceros Edited by Richard H Emslie, Rajan Amin & Richard Kock First Edition, 2009 Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 39 IUCN Founded in 1948, IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of nongovernmental organizations in a unique world partnership: over 1000 members in all, spread across some 160 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. IUCN builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) The IUCN Species Survival Commission is a science-based network of close to 8,000 volunteer experts from almost every country of the world, all working together towards achieving the vision of, “A world that values and conserves present levels of biodiversity.” African Rhino Specialist Group and Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AfRSG/AsRSG) Their mission is to promote the development and long term maintenance of viable populations of the various sub-species of African and Asian rhinos in the wild. Their membership consists of official country representatives from the main range states and a number of specialist members covering a wide range of skills. Wildlife Health Specialist Group (WHSG) The IUCN Wildlife Health Specialist Group is a collaborative multidisciplinary network supporting and promoting the health of wildlife and wildlife management as core components of ecosystem and biodiversity conservation. -

Short Staff Weapons

hort Staff (Jo, Cane, Zhang, Jo Do, Aikijo, Jojutsu, Gun Quan, Hanbo, Walking Stick): Guides, Resources, Links, Bibliography, Media, Lesso Way of the Short Staff Self-Defense Arts and Fitness Exercises Using a Short Staff: Cane, Jo, Zhang, Gun, Four Foot Staff, Guai Gun, Walking Stick Whip Staff, 13 Hands Staff, Cudgel, Quarter Staff, Hanbo Martial Arts Ways: Jodo, Aikijo, Jojutsu, Gun Quan, Zhang Quan Bibliographies, Links, Resources, Guides, Media, Instructions, Forms, History Cane Aikido Jo Karate Jo Taijiquan Cane Tai Chi Staff Bo, Long Staff, Spear Techniques Quotations Other Short Staff Arts Lore, Legends, Magick My Practices Purchasing and Sizing a Staff or Cane Walking Fitness Valley Spirit Taijiquan Research by Michael P. Garofalo February 6, 2009 Page 1 hort Staff (Jo, Cane, Zhang, Jo Do, Aikijo, Jojutsu, Gun Quan, Hanbo, Walking Stick): Guides, Resources, Links, Bibliography, Media, Lesso Valley Spirit Taijiquan I began to revise and update this webpage in September, 2008. Its purpose is to record my travels along the Way of the Short Staff. I have already prepared a fairly comprehensive and popular webpage on Staff Weapons. During 2009, this webpage will be researched and expanded so as to exclusively focus on my practice and knowledge of the Way of the Short Staff. By "short staff" I mean a straight wooden staff or cane from 30" to 50" long. I welcome suggestions, comments and information from readers about good resources, links, books, pamphlets, videos, DVDs, VCDs, schools, workshops, events, techniques, forms, etc.. Please send your email to Mike Garofalo. In 2009, I will be learning by studying, practicing, and documenting three different styles of the cane.