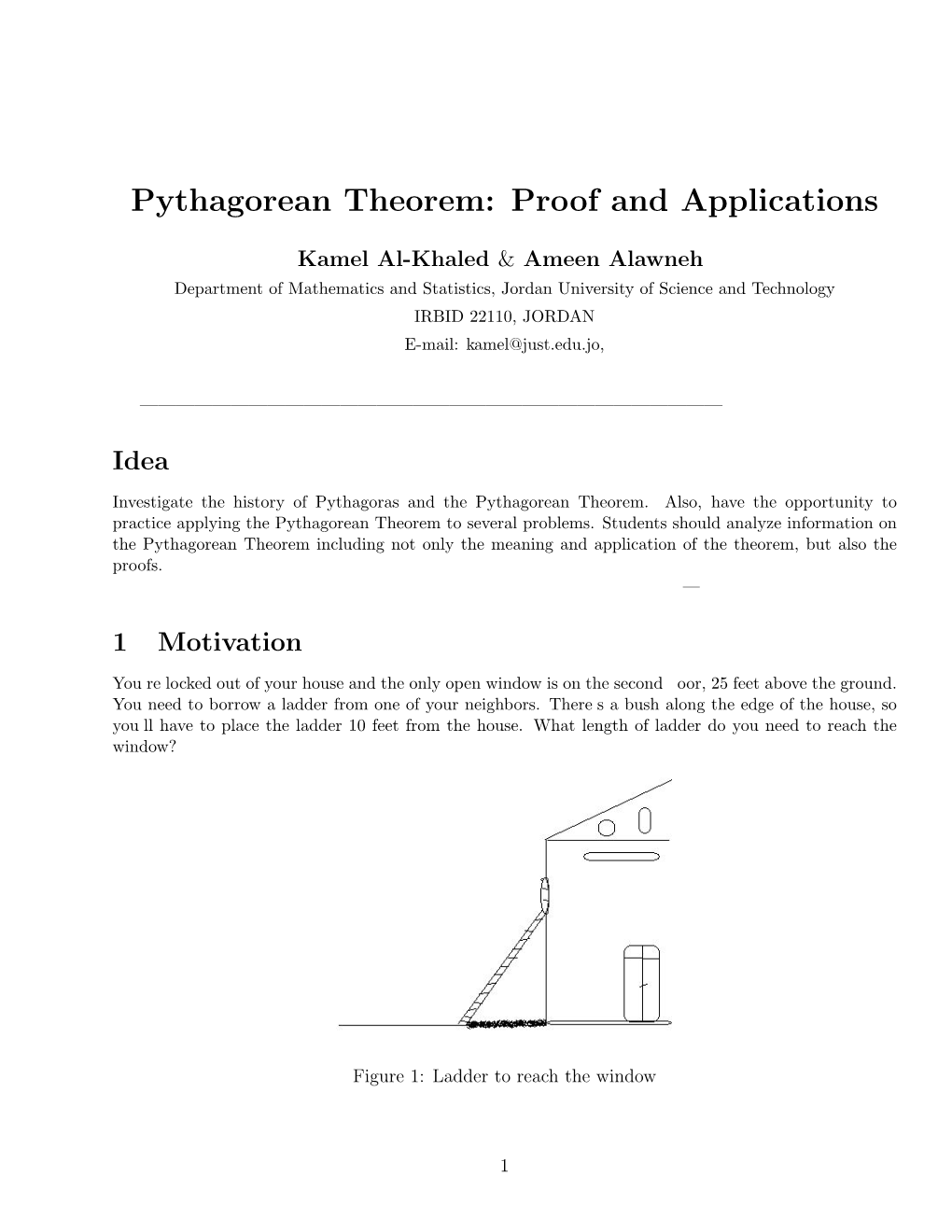

Pythagorean Theorem: Proof and Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometry Course Outline

GEOMETRY COURSE OUTLINE Content Area Formative Assessment # of Lessons Days G0 INTRO AND CONSTRUCTION 12 G-CO Congruence 12, 13 G1 BASIC DEFINITIONS AND RIGID MOTION Representing and 20 G-CO Congruence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Combining Transformations Analyzing Congruency Proofs G2 GEOMETRIC RELATIONSHIPS AND PROPERTIES Evaluating Statements 15 G-CO Congruence 9, 10, 11 About Length and Area G-C Circles 3 Inscribing and Circumscribing Right Triangles G3 SIMILARITY Geometry Problems: 20 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 1, 2, 3, Circles and Triangles 4, 5 Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem M1 GEOMETRIC MODELING 1 Solving Geometry 7 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 Problems: Floodlights G4 COORDINATE GEOMETRY Finding Equations of 15 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 4, 5, Parallel and 6, 7 Perpendicular Lines G5 CIRCLES AND CONICS Equations of Circles 1 15 G-C Circles 1, 2, 5 Equations of Circles 2 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 1, 2 Sectors of Circles G6 GEOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS AND DIMENSIONS Evaluating Statements 15 G-GMD 1, 3, 4 About Enlargements (2D & 3D) 2D Representations of 3D Objects G7 TRIONOMETRIC RATIOS Calculating Volumes of 15 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 6, 7, 8 Compound Objects M2 GEOMETRIC MODELING 2 Modeling: Rolling Cups 10 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 TOTAL: 144 HIGH SCHOOL OVERVIEW Algebra 1 Geometry Algebra 2 A0 Introduction G0 Introduction and A0 Introduction Construction A1 Modeling With Functions G1 Basic Definitions and Rigid -

Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics

chapter 8 Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics F. Javier Campos-Daroca 1 Socrates vs. Epicurus: Ancients and Moderns According to an ancient genre of philosophical historiography, Epicurus and Socrates belonged to distinct traditions or “successions” (diadochai) of philosophers. Diogenes Laertius schematizes this arrangement in the following way: Socrates is placed in the middle of the Ionian tradition, which starts with Thales and Anaximander and subsequently branches out into different schools of thought. The “Italian succession” initiated by Pherecydes and Pythagoras comes to an end with Epicurus.1 Modern views, on the other hand, stress the contrast between Socrates and Epicurus as one between two opposing “ideal types” of philosopher, especially in their ways of teaching and claims about the good life.2 Both ancients and moderns appear to agree on the convenience of keeping Socrates and Epicurus apart, this difference being considered a fundamental lineament of ancient philosophy. As for the ancients, however, we know that other arrangements of philosophical traditions, ones that allowed certain connections between Epicureanism and Socratism, circulated in Hellenistic times.3 Modern outlooks on the issue are also becoming more nuanced. 1 DL 1.13 (Dorandi 2013). An overview of ancient genres of philosophical history can be seen in Mansfeld 1999, 16–25. On Diogenes’ scheme of successions and other late antique versions of it, see Kienle 1961, 3–39. 2 According to Riley 1980, 56, “there was a fundamental difference of opinion concerning the role of the philosopher and his behavior towards his students.” In Riley’s view, “Epicurean criticism was concerned mainly with philosophical style,” not with doctrines (which would explain why Plato was not as heavily attacked as Socrates). -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes. -

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

Lecture 4. Pythagoras' Theorem and the Pythagoreans

Lecture 4. Pythagoras' Theorem and the Pythagoreans Figure 4.1 Pythagoras was born on the Island of Samos Pythagoras Pythagoras (born between 580 and 572 B.C., died about 497 B.C.) was born on the island of Samos, just off the coast of Asia Minor1. He was the earliest important philosopher who made important contributions in mathematics, astronomy, and the theory of music. Pythagoras is credited with introduction the words \philosophy," meaning love of wis- dom, and \mathematics" - the learned disciplines.2 Pythagoras is famous for establishing the theorem under his name: Pythagoras' theorem, which is well known to every educated per- son. Pythagoras' theorem was known to the Babylonians 1000 years earlier but Pythagoras may have been the first to prove it. Pythagoras did spend some time with Thales in Miletus. Probably by the suggestion of Thales, Pythagoras traveled to other places, including Egypt and Babylon, where he may have learned some mathematics. He eventually settled in Groton, a Greek settlement in southern Italy. In fact, he spent most of his life in the Greek colonies in Sicily and 1Asia Minor is a region of Western Asia, comprising most of the modern Republic of Turkey. 2Is God a mathematician ? Mario Livio, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, New York-London-Toronto- Sydney, 2010, p. 15. 23 southern Italy. In Groton, he founded a religious, scientific, and philosophical organization. It was a formal school, in some sense a brotherhood, and in some sense a monastery. In that organization, membership was limited and very secretive; members learned from leaders and received education in religion. -

Pythagorean Theorem Word Problems Ws #1 Name ______

Pythagorean Theorem word problems ws #1 Name __________________________ Solve each of the following. Please draw a picture and use the Pythagorean Theorem to solve. Be sure to label all answers and leave answers in exact simplified form. 1. The bottom of a ladder must be placed 3 feet from a wall. The ladder is 12 feet long. How far above the ground does the ladder touch the wall? 2. A soccer field is a rectangle 90 meters wide and 120 meters long. The coach asks players to run from one corner to the corner diagonally across the field. How far do the players run? 3. How far from the base of the house do you need to place a 15’ ladder so that it exactly reaches the top of a 12’ wall? 4. What is the length of the diagonal of a 10 cm by 15 cm rectangle? 5. The diagonal of a rectangle is 25 in. The width is 15 in. What is the area of the rectangle? 6. Two sides of a right triangle are 8” and 12”. A. Find the the area of the triangle if 8 and 12 are legs. B. Find the area of the triangle if 8 and 12 are a leg and hypotenuse. 7. The area of a square is 81 cm2. Find the perimeter of the square. 8. An isosceles triangle has congruent sides of 20 cm. The base is 10 cm. What is the area of the triangle? 9. A baseball diamond is a square that is 90’ on each side. -

5-7 the Pythagorean Theorem 5-7 the Pythagorean Theorem

55-7-7 TheThe Pythagorean Pythagorean Theorem Theorem Warm Up Lesson Presentation Lesson Quiz HoltHolt McDougal Geometry Geometry 5-7 The Pythagorean Theorem Warm Up Classify each triangle by its angle measures. 1. 2. acute right 3. Simplify 12 4. If a = 6, b = 7, and c = 12, find a2 + b2 2 and find c . Which value is greater? 2 85; 144; c Holt McDougal Geometry 5-7 The Pythagorean Theorem Objectives Use the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse to solve problems. Use Pythagorean inequalities to classify triangles. Holt McDougal Geometry 5-7 The Pythagorean Theorem Vocabulary Pythagorean triple Holt McDougal Geometry 5-7 The Pythagorean Theorem The Pythagorean Theorem is probably the most famous mathematical relationship. As you learned in Lesson 1-6, it states that in a right triangle, the sum of the squares of the lengths of the legs equals the square of the length of the hypotenuse. a2 + b2 = c2 Holt McDougal Geometry 5-7 The Pythagorean Theorem Example 1A: Using the Pythagorean Theorem Find the value of x. Give your answer in simplest radical form. a2 + b2 = c2 Pythagorean Theorem 22 + 62 = x2 Substitute 2 for a, 6 for b, and x for c. 40 = x2 Simplify. Find the positive square root. Simplify the radical. Holt McDougal Geometry 5-7 The Pythagorean Theorem Example 1B: Using the Pythagorean Theorem Find the value of x. Give your answer in simplest radical form. a2 + b2 = c2 Pythagorean Theorem (x – 2)2 + 42 = x2 Substitute x – 2 for a, 4 for b, and x for c. x2 – 4x + 4 + 16 = x2 Multiply. -

Heraclitus on Pythagoras

Leonid Zhmud Heraclitus on Pythagoras By the time of Heraclitus, criticism of one’s predecessors and contemporaries had long been an established literary tradition. It had been successfully prac ticed since Hesiod by many poets and prose writers.1 No one, however, practiced criticism in the form of persistent and methodical attacks on both previous and current intellectual traditions as effectively as Heraclitus. Indeed, his biting criti cism was a part of his philosophical method and, on an even deeper level, of his selfappraisal and selfunderstanding, since he alone pretended to know the correct way to understand the underlying reality, unattainable even for the wisest men of Greece. Of all the celebrities figuring in Heraclitus’ fragments only Bias, one of the Seven Sages, is mentioned approvingly (DK 22 B 39), while another Sage, Thales, is the only one mentioned neutrally, as an astronomer (DK 22 B 38). All the others named by Heraclitus, which is to say the three most famous poets, Homer, Hesiod and Archilochus, the philosophical poet Xenophanes, Pythago ras, widely known for his manifold wisdom, and finally, the historian and geog rapher Hecataeus – are given their share of opprobrium.2 Despite all the intensity of Heraclitus’ attacks on these famous individuals, one cannot say that there was much personal in them. He was not engaged in ordi nary polemics with his contemporaries, as for example Xenophanes, Simonides or Pindar were.3 Xenophanes and Hecataeus, who were alive when his book was written, appear only once in his fragments, and even then only in the company of two more famous people, Hesiod and Pythagoras (DK 22 B 40). -

The Pythagorean Theorem and Area: Postulates Into Theorems Paul A

Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal Issue 25 Article 13 8-1-2001 The Pythagorean Theorem and Area: Postulates into Theorems Paul A. Kennedy Texas State University Kenneth Evans Texas State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmnj Part of the Mathematics Commons, Science and Mathematics Education Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Kennedy, Paul A. and Evans, Kenneth (2001) "The Pythagorean Theorem and Area: Postulates into Theorems," Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal: Iss. 25, Article 13. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmnj/vol1/iss25/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Pythagorean Theorem and Area: Postulates into Theorems Paul A. Kennedy Contributing Author: Department of Mathematics Kenneth Evans Southwest Texas State University Department of Mathematics, Retired San Marcos, TX 78666-4616 Southwest Texas State University [email protected] San Marcos, TX 78666-4616 Considerable time is spent in high school geometry equal to the area of the square on the hypotenuse. building an axiomatic system that allows students to understand and prove interesting theorems. In tradi- tional geometry classrooms, the theorems were treated in isolation with some of -

The Pythagorean Theorem

6.2 The Pythagorean Theorem How are the lengths of the sides of a right STATES triangle related? STANDARDS MA.8.G.2.4 MA.8.A.6.4 Pythagoras was a Greek mathematician and philosopher who discovered one of the most famous rules in mathematics. In mathematics, a rule is called a theorem. So, the rule that Pythagoras discovered is called the Pythagorean Theorem. Pythagoras (c. 570 B.C.–c. 490 B.C.) 1 ACTIVITY: Discovering the Pythagorean Theorem Work with a partner. a. On grid paper, draw any right triangle. Label the lengths of the two shorter sides (the legs) a and b. c2 c a a2 b. Label the length of the longest side (the hypotenuse) c. b b2 c . Draw squares along each of the three sides. Label the areas of the three squares a 2, b 2, and c 2. d. Cut out the three squares. Make eight copies of the right triangle and cut them out. a2 Arrange the fi gures to form 2 two identical larger squares. c b2 e. What does this tell you about the relationship among a 2, b 2, and c 2? 236 Chapter 6 Square Roots and the Pythagorean Theorem 2 ACTIVITY: Finding the Length of the Hypotenuse Work with a partner. Use the result of Activity 1 to fi nd the length of the hypotenuse of each right triangle. a. b. c 10 c 3 24 4 c. d. c 0.6 2 c 3 0.8 1 2 3 ACTIVITY: Finding the Length of a Leg Work with a partner. -

The Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, but Having an Important

,1(70 THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES. ftonton: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. ambriDse: DEIGHTON, BELL, AND CO. ltip>ifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS. #tto Hork: MACMILLAX AND CO. THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES WITH INTRODUCTION AND EXPLANATORY NOTES. AX ESSAY WHICH OBTAINED THE HARE PRIZE IX THE YEAR 1889. BY A. C. PEARSON, M.A. LATE SCHOLAR OF CHRIST S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. LONDON: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE. 1891 [All Rights reserved.] Cambridge : PBIXTKIi BY C. J. CLAY, M.A. AND SONS, AT THK UNIVERSITY PRKSS. PREFACE. S dissertation is published in accordance with thr conditions attached to the Hare Prize, and appears nearly in its original form. For many reasons, however, I should have desired to subject the work to a more under the searching revision than has been practicable circumstances. Indeed, error is especially difficult t<> avoid in dealing with a large body of scattered authorities, a the majority of which can only be consulted in public- library. to be for The obligations, which require acknowledged of Zeno and the present collection of the fragments former are Cleanthes, are both special and general. The Philo- soon disposed of. In the Neue Jahrbticher fur Wellmann an lofjie for 1878, p. 435 foil., published article on Zeno of Citium, which was the first serious of Zeno from that attempt to discriminate the teaching of Wellmann were of the Stoa in general. The omissions of the supplied and the first complete collection fragments of Cleanthes was made by Wachsmuth in two Gottingen I programs published in 187-i LS75 (Commentationes s et II de Zenone Citiensi et Cleaitt/ie Assio). -

The Euclidean Mousetrap

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilPapers Originally in Journal of Idealistic Studies 38(3): 209-220 (2008). Please quote from published version. THE EUCLIDEAN MOUSETRAP: SCHOPENHAUER’S CRITICISM OF THE SYNTHETIC METHOD IN GEOMETRY Jason M. Costanzo Abstract In his doctoral dissertation On the Principle of Sufficient Reason, Arthur Schopenhauer there outlines a critique of Euclidean geometry on the basis of the changing nature of mathematics, and hence of demonstration, as a result of Kantian idealism. According to Schopenhauer, Euclid treats geometry synthetically, proceeding from the simple to the complex, from the known to the unknown, “synthesizing” later proofs on the basis of earlier ones. Such a method, although proving the case logically, nevertheless fails to attain the raison d’être of the entity. In order to obtain this, a separate method is required, which Schopenhauer refers to as “analysis”, thus echoing a method already in practice among the early Greek geometers, with however some significant differences. In this essay, I here discuss Schopenhauer’s criticism of synthesis in Euclid’s Elements, and the nature and relevance of his own method of analysis. The influence of philosophy upon the development of mathematics is readily seen in the practice among mathematicians of offering a demonstration or “proof” of the many theorems and problems which they encounter. This practice finds its origin among the early Greek geometricians and arithmeticians, during a time in which philosophy and mathematics intermingled at an unprecedented level, and a period in which rationalism enjoyed preeminence.