Variation and Opacity Abstract

Total Page:16

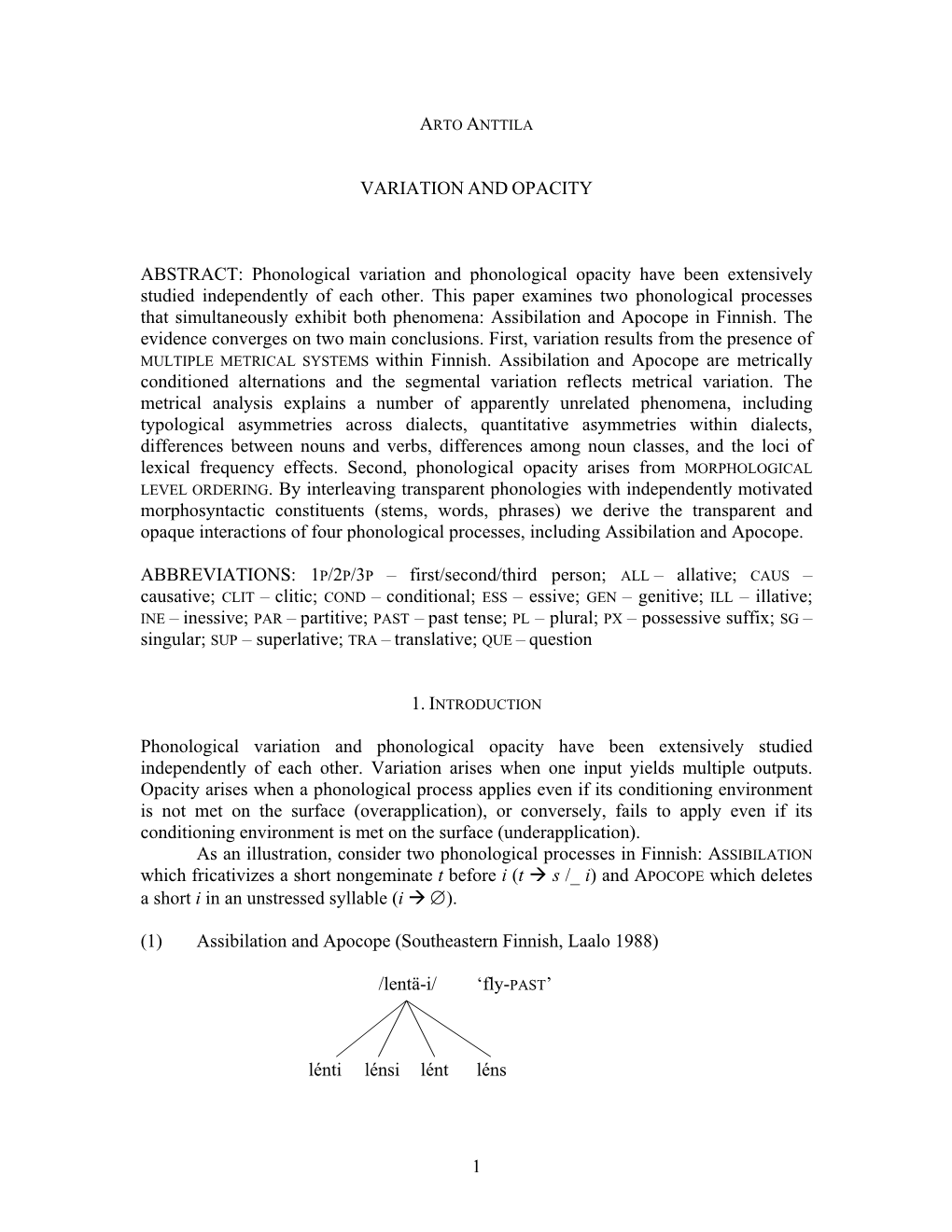

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opacity and Cyclicity

Opacity and Cyclicity Paul Kiparsky Stanford University Phonological opacity and paradigmatic effects (“synchronic analogy”) have long been of interest in relation to change, naturalness, and the phonology/morphology interface. Their investigation has now acquired a new urgency, because they call into question OT’s postulate that constraints are evaluated in parallel. Conceptu- ally, parallelism is one of the basic and most interesting tenets of OT, and so there are good methodological reasons to try hard to save it in the face of such recal- citrant data. The price to be paid for it is the introduction of otherwise unneeded powerful new types of Faithfulness constraints, such as Output/Output (O/O) con- straints, Paradigm Uniformity constraints, and Sympathy constraints, which have turned out to compromise the OT program very severely. The alternative to this approach is to abandon full parallelism in favor of strat- ified constraint systems. This has the compensating advantage of maintaining a restrictive and well-defined constraint inventory, as originally envisaged in OT. More importantly, it achieves some genuine explanations by relating the strat- ification motivated by opacity and cyclicity to the intrinsic morphological and prosodic constituency of words and phrases, as characterized by the Stem, Word, and Postlexical levels of Lexical Phonology and Morphology (Booij 1996; 1997; Orgun 1996; Bermudez-Otero 1999). I shall refer to this approach as LPM-OT, and outline how it offers a superior account of the benchmark data that Kager 1999 discusses in Ch. 6 of his book.1 LPM-OT’s goal is to reduce cyclicity to I/O faithfulness, and opacity to inter- level constraint masking. -

Transparency in Language a Typological Study

Transparency in language A typological study Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration © 2011: Sanne Leufkens – image from the performance ‘Celebration’ ISBN: 978-94-6093-162-8 NUR 616 Copyright © 2015: Sterre Leufkens. All rights reserved. Transparency in language A typological study ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op vrijdag 23 januari 2015, te 10.00 uur door Sterre Cécile Leufkens geboren te Delft Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Hengeveld Copromotor: Dr. N.S.H. Smith Overige leden: Prof. dr. E.O. Aboh Dr. J. Audring Prof. dr. Ö. Dahl Prof. dr. M.E. Keizer Prof. dr. F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen i Acknowledgments When I speak about my PhD project, it appears to cover a time-span of four years, in which I performed a number of actions that resulted in this book. In fact, the limits of the project are not so clear. It started when I first heard about linguistics, and it will end when we all stop thinking about transparency, which hopefully will not be the case any time soon. Moreover, even though I might have spent most time and effort to ‘complete’ this project, it is definitely not just my work. Many people have contributed directly or indirectly, by thinking about transparency, or thinking about me. -

Observations on the Phonetic Realization of Opaque Schwa in Southern French

http://dx.doi.org/10.17959/sppm.2015.21.3.457 457 Observations on the phonetic realization of opaque * schwa in Southern French Julien Eychenne (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) Eychenne, Julien. 2015. Observations on the phonetic realization of opaque schwa in Southern French. Studies in Phonetics, Phonology and Morphology 21.3. 457-494. This paper discusses a little-known case of opacity found in some southern varieties of French, where the vowel /ə/, which is footed in the dependent syllable of a trochee, is usually realized as [ø], like the full vowel /Œ/. This case of opacity is particularly noteworthy because the opaque generalization is suprasegmental, not segmental. I show that, depending on how the phenomenon is analyzed derivationally, it simultaneously displays symptoms of counterbleeding and counterfeeding opacity. A phonetic analysis of data from one representative speaker is carried out, and it is shown that the neutralization between /ə/ and /Œ/ is complete in this idiolect. Implications for the structure of lexical representations and for models of phonology are discussed in light of these results. (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) Keywords: schwa, Southern French, opacity 1. Introduction Opacity is one of the most fundamental issues in generative phonological theory. The traditional view of opacity, due to Kiparsky (1971, 1973) and framed within the derivational framework of The Sound Pattern of English (henceforth SPE, Chomsky and Halle 1968), goes as follows: (1) Opacity (Kiparsky 1973: 79) A phonological rule P of the form A → B / C__D is opaque if there are * An early version of this work was presented at the Linguistics Colloquium of the English Linguistics Department, Graduate School at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. -

Modeling the Acquisition of Phonological Interactions: Biases and Generalization

Modeling the Acquisition of Phonological Interactions: Biases and Generalization Brandon Prickett and Gaja Jarosz1 University of Massachusetts Amherst 1 Introduction Phonological processes in a language have the potential to interact with one another in numerous ways (Kiparsky 1968, 1971). Two relatively common interaction types are bleeding and feeding interactions, with (1) showing hypothetical examples of both (for a similar hypothetical example, see Baković 2011). (1) Example of Bleeding and Feeding Interactions Bleeding Feeding Underlying Representation (UR) /esi/ /ise/ [-Low] → [αHigh] / [αHigh]C_ (Vowel Harmony) ese isi [s] → [ʃ] / _[+High] (Palatalization) - iʃi Surface Representation (SR) [ese] [iʃi] In the bleeding interaction above, the underlying form /esi/ undergoes harmony, since the /e/ and /i/ have different values for the feature [High]. Since the harmony is progressive, the /i/ assimilates to the /e/ and can no longer trigger the palatalization process (which occurs after harmony), resulting in a surface form of [ese]. The feeding interaction has the opposite effect, with an underlying /e/ becoming a high vowel due to harmony and then triggering the palatalization process to create the SR [iʃi]. The crucial difference between the two interaction types in this example is whether the UR undergoes lowering or raising due to the harmony process. Two other interactions can be produced using these same URs by applying the two rules in the opposite order. These are called Counterbleeding and Counterfeeding interactions and are shown in (2). (2) Example of Counterbleeding and Counterfeeding Interactions Counterbleeding Counterfeeding UR /esi/ /ise/ Palatalization eʃi - Vowel Harmony eʃe isi SR [eʃe] [isi] In the counterbleeding interaction, both palatalization and harmony are able to change the underlying representation, but the motivation for palatalizing (i.e. -

Phonological Abstractness in the Mental Lexicon

Phonological Abstractness in the Mental Lexicon Eric Bakovi´c,Jeffrey Heinz, Jonathan Rawski To Appear in The Oxford Handbook of the Mental Lexicon 1 Talking and Listening When we try to understand how we speak, and how we listen, an unavoidable fact is that we use the same vocabulary items again and again. So, not only are these stored in memory, but they are learned on a language-specific basis. In this way, we directly confront the issue of mental representations of speech; that is, something about how we store, retrieve and remember units of speech. What are these units? What are these mental representations? These questions are central to generative phonology, a fact reflected in the title of a collection of important papers by Morris Halle, a founder of the field: From Memory to Speech and Back Again (Halle, 2003). In this chapter we review some of the most basic | and most fascinating | conclusions and open questions in phonology regarding how abstract these mental representations of speech are. In an era of big data, and data mining, the prevailing attitude in science and scientific observation seems to be to store every last detail, to never assume any detail is irrelevant, no matter how small, because you never know when it may in fact make a difference somewhere. This attitude is also present in the psychology of language, where it has been shown that people are sensitive to astounding details of aspects of speech reflecting people's age, gender, social status, neighborhood, and health (Coleman, 2002; Pierrehumbert, 2002; Johnson, 2006). -

Speakers Treat Transparent and Opaque Alternation Patterns Differently — Evidence from Chinese Tone Sandhi*

This is a printout of the final PDF file and has been approved by me, the author. Any mistakes in this printout will not be fixed by the publisher. Here is my signature and the date 06/10/2018 Speakers Treat Transparent and Opaque Alternation Patterns Differently — Evidence from Chinese Tone Sandhi* Jie Zhang 1. Introduction 1.1 Opacity The study of opacity has had a long tradition in generative phonology. Kiparsky (1973: p.79) defined two types of opacity for a phonological rule, as in (1). The first type is also known as underapplication opacity, and the opaque rule is non-surface-true; the second type is also known as overapplication opacity, and the opaque rule is non-surface-apparent (e.g., Bakovic 2007). (1) Opacity: A phonological rule P of the form A → B / C __ D is opaque if there are surface structures with any of the following characteristics: (a) Instance of A in the environment C __ D; (b) Instance of B derived by P in environments other than C __ D. In the rule-based framework, opacity can generally be derived by ordering the opaque rule before another rule that could either set up or destroy the application of the opaque rule (but see Bakovic 2007, 2011, who advocates the decoupling of opacity and rule ordering). In a surface-oriented theory like Optimality Theory (OT; Prince and Smolensky 1993/2004), however, opacity poses significant challenges. Without modification to the theory, neither underapplication nor overapplication opacity can be straightforwardly derived. A number of general solutions for opacity have been proposed within OT, including the Sympathy Theory (McCarthy 1999), Stratal OT (Kiparsky 2000, Nazarov and Pater 2017), OT with Candidate Chains (OT-CC; McCarthy 2007), and Serial Markedness Reduction (Jarosz 2014, 2016). -

The Acquisition of Phonological Opacity

The acquisition of phonological opacity Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero University of Newcastle upon Tyne Abstract. This paper argues that Stratal OT is explanatorily superior to alternative OT treatments of phonological opacity (notably, Sympathy Theory). It shows that Stratal OT supports a learning model that accounts for the acquisition of opaque grammars with a minimum of machinery. The model is illustrated with a case study of the classical counterbleeding interaction between Diphthong Raising and Flapping in Canadian English. 1. Phonological opacity: Stratal OT vs Sympathy Theory Following the appearance of Prince & Smolensky (1993), phonologists were quick to realize that, in its original version, Optimality Theory (OT) was unable to describe a large set of phonological phenomena previously modelled by means of opaque rules. Ten years later, opacity remains the severest challenge confronting OT phonology. The problem is crucial because opacity effects constitute one of the clearest instances of Plato’s Problem (Chomsky 1986) in phonology: learners face the task of acquiring generalizations that are not true on the surface. The ability to explain the acquisition of opaque grammars should accordingly be regarded as one of the main criteria by which generative theories of phonology are to be judged. Among the variants of OT phonology currently on offer, two claim to provide a comprehensive solution to the problem of opacity: Sympathy Theory (McCarthy 1999, 2003) and Stratal OT (Bermúdez-Otero 1999b; Kiparsky 2000, forthcoming). In this paper, I compare the strategies whereby these two phonological models seek to achieve —and indeed transcend— explanatory adequacy: • I shall first consider the formal restrictions that each theory imposes on the complexity of opaque effects (§2). -

Role of Phonological Opacity and Morphological Knowledge in Predicting Reading

Role of Phonological Opacity and Morphological Knowledge in Predicting Reading Skills in School-Age Children A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Health Sciences and Professions of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Gayatri Ram December 2013 © 2013 Gayatri Ram. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Role of Phonological Opacity and Morphological Knowledge in Predicting Reading Skills in School-Age Children by GAYATRI RAM has been approved for the School of Rehabilitation and Communication Sciences and the College of Health Sciences and Professions by Sally A. Marinellie Associate Professor of Health Sciences and Professions Randy Leite Dean, College of Health Sciences and Professions 3 Abstract RAM, GAYATRI, Ph.D., December 2013, Speech-Language Science Role of Phonological Opacity and Morphological Knowledge in Predicting Reading Skills in School-Age Children Director of Dissertation: Sally A. Marinellie The aim of the present study was to investigate different aspects of morphological knowledge for phonologically transparent and opaque derived words in young school-age children. We were also interested in identifying morphological predictors of decoding and reading comprehension in school-age children. A total of 53 typically developing children in grade 3 participated in the project. All children completed three experimental tasks measuring different aspects of morphological knowledge for both kinds of derived words as well as standardized measures for decoding, passage comprehension and phonological awareness. Results indicated that children performed better on phonologically transparent derived words as compared to opaque derived words on all three morphological knowledge tasks. Further, results of hierarchical regression analyses revealed that both phonological awareness and morphological knowledge accounted for unique variance in reading skills in children. -

Handouts for Advanced Phonology: a Course Packet Steve Parker GIAL

Handouts for Advanced Phonology: A Course Packet Steve Parker GIAL and SIL International Dallas, 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Steve Parker and other contributors Page 1 of 304 Preface This set of materials is designed to be used as handouts accompanying an advanced course in phonology, particularly at the graduate level. It is specifically intended to be used in conjunction with two textbooks: Phonology in generative grammar (Kenstowicz 1994), and Optimality theory (Kager 1999). However, this course packet could potentially also be adapted for use with other phonology textbooks. The materials included here have been developed by myself and others over many years, in conjunction with courses in phonology taught at SIL programs in North Dakota, Oregon, Dallas, and Norman, OK. Most recently I have used them at GIAL. Many of the special phonetic characters appearing in these materials use IPA fonts available as freeware from the SIL International website. Unless indicated to the contrary on specific individual handouts, all materials used in this packet are the copyright of Steve Parker. These documents are intended primarily for educational use. You may make copies of these works for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. However, republication or commercial use of these materials is expressly prohibited without my prior written consent. Steve Parker Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics Dallas, 2016 Page 2 of 304 1 Table of contents: list of handouts included in this packet Day 1: Distinctive features — their definitions and uses -Pike’s premises for phonological analysis ......................................................................... 7 -Phonemics analysis flow chart .......................................................................................... -

Overapplication Opacity in Phonological Acquisition

Overapplication Opacity in Phonological Acquisition Olga Urek CASTL/University of Tromsø Abstract Phonological opacity is a challenge for parallel OT, which does not allow for intermediate levels of representation. Several modifications of the theory have been proposed over the years to incorporate opacity, all of them falling short of accounting for spontaneous opacity effects in developing grammars. In this paper I demonstrate that if certain independently motivated adjustments are made to the recent OT- based theory of opacity called Optimality Theory with Candidate Chains (OT-CC, see McCarthy 2007), it can successfully deal with spontaneous opacity effects. 1. Opacity in Optimality Theory The term ‘phonological opacity’ refers to cases where a surface form of some language L appears to have exceptionally undergone (overapplication or counterbleeding opacity) or failed to undergo (underapplication or counterfeeding opacity) a certain phonological process active in language L. (1) Opacity (Kiparsky 1973) A phonological rule P of the form A → B / C_D is opaque if there are surface structures with either of the following characteristics: a. instances of A in the environment C_D. b. instances of B derived by P that occur in environments other than C_D. Serialist accounts of opacity crucially rely on the existence of some intermediate form that deviates from the input and from the actual output. According to Prince & Smolensky (1993:6), in ‘classic’ Optimality Theory (OT) the “Input à Output map has no internal structure: all possible variants are produced by Gen in one step and evaluated in parallel”. Precisely this property makes opacity a challenging issue for OT. There have been many attempts to incorporate opacity in OT, which can be roughly subdivided into two large (and partly overlapping) groups: those that rely on expanding some basic assumptions about the nature of underlying representations or the constraint component Con and those that make reference to forms distinct from the input and the actual output. -

The Routledge Handbook of Phonological Theory Current Issues

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 26 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Handbook of Phonological Theory S. J. Hannahs, Anna R. K. Bosch Current issues and directions in Optimality Theory Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315675428-3 Martin Krämer Published online on: 29 Dec 2017 How to cite :- Martin Krämer. 29 Dec 2017, Current issues and directions in Optimality Theory from: The Routledge Handbook of Phonological Theory Routledge Accessed on: 26 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315675428-3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 Current issues and directions in Optimality Theory Constraints and their interaction Martin Krämer 3.1 Introduction The first manuscripts on Optimality Theory (henceforth OT; Prince & Smolensky 1993/2004) were circulated in the early nineties, which is roughly a quarter of a century ago. -

Vowel Harmony, Opacity, and Finite-State OT

Vowel Harmony, Opacity, and Finite-State OT Samuel R. Bowman The University of Chicago July 22, 2011 Abstract: In this paper I propose cyclic and stratal extensions to Finite- State Optimality Theory as treatments for vowel harmony and for opaque phenomena more generally. I develop a model of grammar and an ac- companying set of constraints within a software model built on the open- source PyPhon toolkit—a computational implementation of OT’s Gen and EVAL algorithms. 0 Constraint-based grammars and typology Since their introduction in the early nineteen-nineties, constraint-based grammars have been widely used in generative phonology for their ability to describe complex patterns in a way that is simple, cognitively plausible, and easily generalized across languages. In any constraint-based grammar, the great bulk of the generative labor is carried out by violable constraints. In an idealized picture, these constraints are clear and principled descriptions of phenomena that are widely dispreferred across languages, like Dep: do not epenthesize segments. The job of the language user is, for every underlying form, to find a surface form that best satisfies the constraints that matter to their language, and to do so directly, without a sequential derivation. Under the associated richness of the base hypothesis (Prince and Smolensky, 1993/2004), constraint-based grammars are expected to be able to produce an ac- ceptable output for any input, even if (as in crosslinguistic borrowing) that input flagrantly violates basic structural principles of the target language. Because of this, it is quite common for analyses to focus on inputs for which no output satisfies all of the constraints.