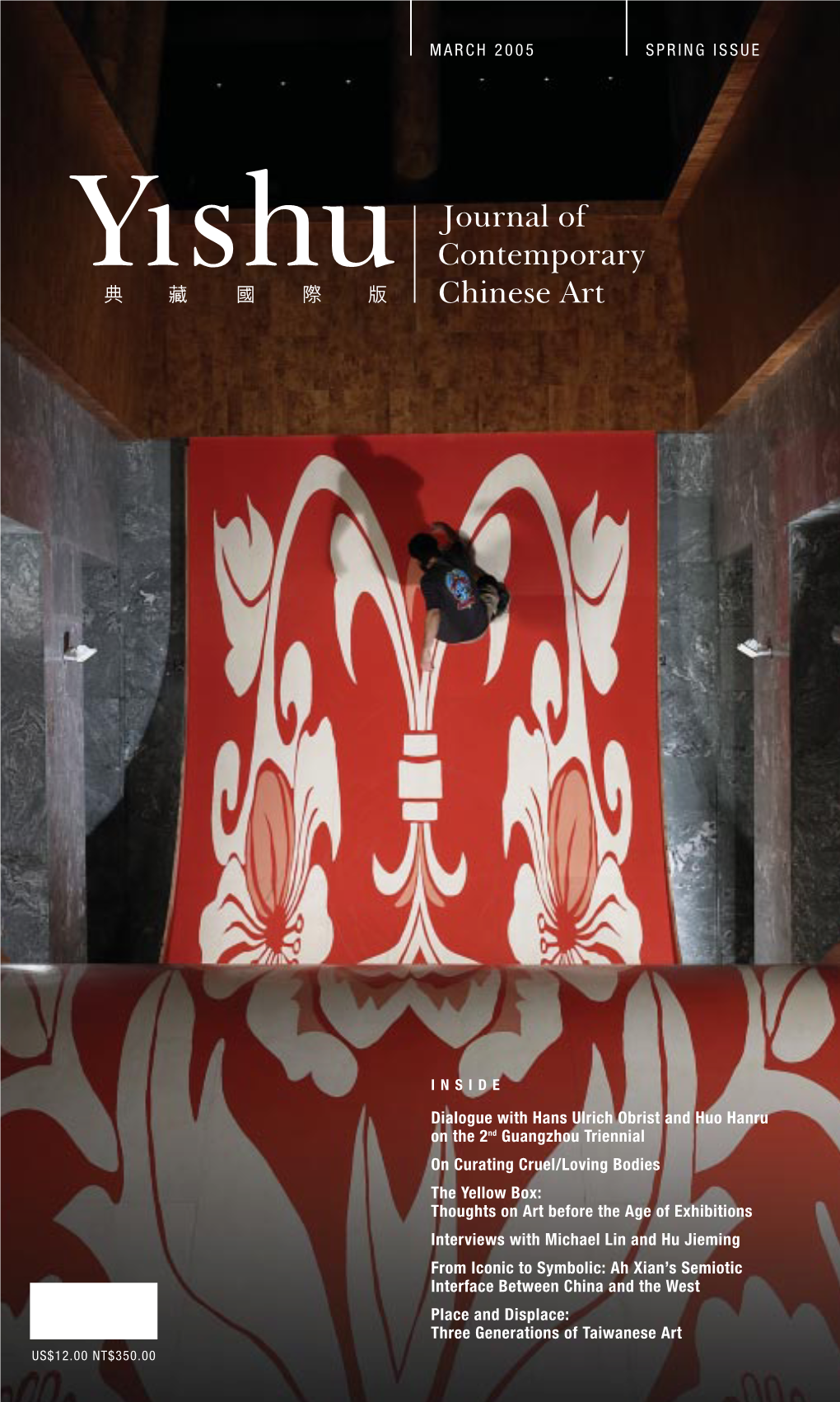

MARCH 2005 SPRING ISSUE Dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conversation with Hou Hanru

Michael Zheng Objectivity, Absurdity, and Social Critique: A Conversation with Hou Hanru January 12, 2009, on the occasion of the exhibition imPOSSIBLE! Eight Chinese Artists Engage Absurdity, San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery and MISSION 17 Left: Zhang Peili, WATER— I. Chinese Video Art in the 1980s Standard Version from the Dictionary Ci Hai, 1991, single- channel colour video, 9 mins. Michael Zheng: Shall we start with how video art began in China? There are 35 secs. Courtesy of the artist. quite a few video works in the exhibition imPOSSIBLE! In the West, video Middle: Zhang Peili, 30 x 30, 1988, single-channel was first used by artists to record performances and events. In that way, at colour video, 9 mins. 32 secs. Courtesy of the artist. least in the West, video art developed hand in hand with performance art. Is Right: Zhang Peili, Document the same true in China? on “Hygiene No. 3,” 1991, single-channel colour video, 24 mins. 45 secs. Courtesy of the artist. Hou Hanru: Yes, the case in China is really similar. In the 980s, when video was introduced to China as an artistic medium, it began to be used by lots of performance artists. They didn’t really have video—they had documentary, like photography, video documentaries, and very, very brief videotapes, because at that time such technology was not so popular. Only professionals had video cameras—mainly people working in television or with advertising companies. The equipment was very expensive, so few artists had access to it. One of the first artists to really use video both to document his performances and to make independent work was Zhang Peili. -

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

September/October 2017 Volume 16, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 5 INSI DE 57th Venice Biennale Conversations with Tang Nannan, Liang Yue, Wong Ping Artist Features: Yin Xiuzhen, Fang Tong The April Photography Society US$12.00 NT$350.00 P RINTED IN TA I WAN 6 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 C ONT ENT S 28 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 On Continuum and Radical Disruption: The Venice Gathering Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker 14 Continuum—Generation by Generation: The Continuation of Artistic Creation at the 57th Venice Biennale: A Conversation with Tang 47 Nannan Ornella De Nigris 28 What Is the Sound of Failed Aspriations? Samson Young's Songs For Disaster Relief Yeewan Koon 37 Miss Underwater: A Conversation with Liang Yue Alexandra Grimmer 47 Sex in the City: Wong Ping in Conversation Stephanie Bailey 71 65 Yin Xiuzhen’s Fluid Sites of Participation: A Communal Space of Communication and Antagonism Vivian Kuang Sheng 78 The Constructed Reality of Immigrants: Fang Tong’s Contrived Photography Dong Yue Su 86 The April Photography Society: A Re-evaluation of Origins, Artworks, and Aims 87 Adam Monohon 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Wong Ping, The Other Side (detail), 2015, 2-channel video, 8 mins., 2 secs. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue 94 Gallery, Hong Kong. We thank JNBY and Lin Li, Cc Foundation and David Chau, Yin Qing, Chen Ping, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. -

Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life

Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Cynthia A. Strickland June 2009 © 2009 Cynthia A. Strickland. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life by CYNTHIA A. STRICKLAND has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Marion Lee Assistant Professor of the Arts Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT STRICKLAND, CYNTHIA A., M.A., June 2009, Art History Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life (90 pp.) Director ofThesis: Marion Lee This thesis examines the circumstances of production and layers of meaning in the installation works of Beijing-based contemporary artist Yin Xiuzhen (b. 1963, Beijing). The approach is to analyze several groups of Yin Xiuzhen’s installations to read how the artist has chosen to map the transformations of the economy, culture, built environment, and power structures, first of her native Beijing and then concentrically outward into the global arena. The result will chronicle the journey of the artist’s successful negotiation of place, space, materials, and message: what I call mapping the fabric of life. As an academically trained oil painter, the 1989 graduate of Capitol Normal University in Beijing initially had limited opportunities to explore a new creative path in art production. During the 1990s, she emerged along with other experimental artists in China who worked to create conceptual art. This thesis focuses on the choices both taken and resisted by Yin Xiuzhen as she developed her artistic voice and located her message within homegrown installations, using as materials fragments and remnants of lives and places. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 282 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. OUR READERS Dai Min Many thanks to the travellers who used the Massive thanks to Dai Lu, Li Jianjun and Cheng Yuan last edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, for all their help and support while in Shanghai, your useful advice and interesting anecdotes: Thomas assistance was invaluable. Gratitude also to Wang Chabrieres, Diana Cioffi, Matti Laitinen, Stine Schou Ying and Ju Weihong for helping out big time and a Lassen, Cristina Marsico, Rachel Roth, Tom Wagener huge thank you to my husband for everything. -

China International Import Expo Presentation of Investment Promotion Activities in Hongkou District

China International Import Expo Presentation of Investment Promotion Activities in Hongkou District Shanghai Hongkou District Comm ission of Commerce (Economy) October 1 0, 2018 SHANGHAI HONGKOU Hongkou district is one of the earliest open areas in China, with a deep cultural background and excellent geographical location. On the south side of Hongkou district lies the Huangpu River and the Wusong River. The North Bund of Hongkou district, the old Bund of Huangpu district and the Lujiazui of Pudong New Area form a golden triangle, separated by the Huangpu River. Hongkou district has a total area of 23.48 k㎡, with a resident population of 800,000. 虹 口 上 海 23.4 k㎡ 6340 k㎡ 中 国 9,634,057 k㎡ SHANGHAI HONGKOU Development Planning of Hongkou District Target for 2020 The Northern Science and Technology Innovation Industry Gathering Area mainly includes the Dabaishu Science and Technology Innovation Center, 1.Establish the Shanghai international Fu Dan-Caida Innovation Area, Tongji Innovation Area, etc. We will focus financial center and international shipping on the renewal and utilization of stock plots, industrial plants and industrial parks. center as import ant functional area 2. Establish an influential creative The Central Commercial and Tourist Sports Development Area is mainly including the area of Hongkou football field area, Sichuan entrepreneurial zone North Road Park-Music Valley, and the area of Ruihong Tiandi. The 3. Establish an accessible and diversified key projects include Financial Street Hailun Center etc. Shanghai cultural heritage development zone. Double Loading Area for Financial and Shipping 4. Establish a high quality urban areas that Industry in the North Bund includes the North Bund are suitable for living, working and Business and Cultural District, Zhoushan Road Historical Creative Block ect. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Copyright by Naoko Kato 2013

Copyright by Naoko Kato 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Naoko Kato Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Through the Kaleidoscope: Uchiyama Bookstore and Sino-Japanese Visionaries in War and Peace Committee: Mark Metzler, Supervisor Nancy Stalker Madeline Hsu Huaiyin Li Robert Oppenheim Through the Kaleidoscope: Uchiyama Bookstore and Sino-Japanese Visionaries in War and Peace by Naoko Kato, B.A., M.A., M.S.I.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Emiko and Haruichi Kato. Through the Kaleidoscope: Uchiyama Bookstore and Sino-Japanese Visionaries in War and Peace Naoko Kato, PhD The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisor: Mark Metzler The Republican period in Chinese history (1911-1949) is generally seen as a series of anti-imperialist and anti-foreign movements that coincide with the development of Chinese nationalism. The continual ties between Chinese nationalists and Japanese intellectuals are often overlooked. In the midst of the Sino-Japanese war, Uchiyama Kanzō, a Christian pacifist who was the owner of the bookstore, acted as a cultural liaison between May Fourth Chinese revolutionaries who were returned students from Japan, and Japanese left-wing activists working for the Communist cause, or visiting Japanese writers eager to meet their Chinese counterparts. I explore the relationship between Japanese and Chinese cultural literati in Shanghai, using Uchiyama Bookstore as the focal point. -

{PDF} Shanghai Architecture Ebook, Epub

SHANGHAI ARCHITECTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne Warr | 340 pages | 01 Feb 2008 | Watermark Press | 9780949284761 | English | Balmain, NSW, Australia Shanghai architecture: the old and the new | Insight Guides Blog Retrieved 16 July Government of Shanghai. Archived from the original on 5 March Retrieved 10 November Archived from the original on 27 January Archived from the original on 26 May Retrieved 5 August Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal People's Government. Archived from the original on 3 October Retrieved 19 July Demographia World Urban Areas. Louis: Demographia. Archived PDF from the original on 3 May Retrieved 15 June Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau. Archived from the original on 24 March Retrieved 24 March Archived from the original on 9 December Retrieved 8 December Global Data Lab China. Retrieved 9 April Retrieved 27 September Long Finance. Retrieved 8 October Top Universities. Retrieved 29 September Archived from the original on 29 September Archived from the original on 16 April Retrieved 11 January Xinmin Evening News in Chinese. Archived from the original on 5 September Retrieved 12 January Archived from the original on 2 October Retrieved 2 October Topographies of Japanese Modernism. Columbia University Press. Daily Press. Archived from the original on 28 September Retrieved 29 July Archived from the original on 30 August Retrieved 4 July Retrieved 24 November Archived from the original on 16 June Retrieved 26 April Archived from the original on 1 October Retrieved 1 October Archived from the original on 11 September Volume 1. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 6 May Retrieved 2 May Office of Shanghai Chronicles. -

The Shanghai Pavilion Room (Tingzijian) in Literature, 1920-1940

THREE FACES OF A SPACE: THE SHANGHAI PAVILION ROOM (TINGZIJIAN) IN LITERATURE, 1920-1940 by Jingyi Zhang B.A., Fudan University, 2015 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May. 2017 © Jingyi Zhang, 2017 Abstract From the 1920s to the 1940s, the pavilion room, or Tingzijian—the small room above the kitchen in an alleyway house—accommodated many Shanghai sojourners. Tingzijian functioned as lodging and as a social space for young writers and artists. For many lodger-writers, the Tingzijian was a temporary residence before they left around 1941. In the interim, Tingzijian life became a burgeoning literary subject, even a recognized literary category. This study explores what meanings people ascribed to Tingzijian, and the historical and the artistic function of the space in Chinese literature of the 1920s and 1930s. Scholars have traditionally viewed “Tingzijian literature” as the province of leftist “Tingzijian literati” (wenren) who later transformed into revolutionaries; this study reveals the involvement a much greater variety of writers. We find a cross section of the literary field, from famous writers like Ba Jin 巴金 and Ding Ling 丁玲, for whom living in a Tingzijian was an important stage in their transition from the margins to the center of the literary field, to a constellation of obscure tabloid writers concerned less with revolution than with common urbanites’ -

Art and Visual Culture in Contemporary Beijing (1978-2012)

Infrastructures of Critique: Art and Visual Culture in Contemporary Beijing (1978-2012) by Elizabeth Chamberlin Parke A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Elizabeth Chamberlin Parke 2016 Infrastructures of Critique: Art and Visual Culture in Contemporary Beijing (1978-2012) Elizabeth Chamberlin Parke Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation is a story about relationships between artists, their work, and the physical infrastructure of Beijing. I argue that infrastructure’s utilitarianism has relegated it to a category of nothing to see, and that this tautology effectively shrouds other possible interpretations. My findings establish counter-narratives and critiques of Beijing, a city at once an immerging global capital city, and an urban space fraught with competing ways of seeing, those crafted by the state and those of artists. Statecraft in this dissertation is conceptualized as both the art of managing building projects that function to control Beijing’s public spaces, harnessing the thing-power of infrastructure, and the enforcement of everyday rituals that surround Beijinger’s interactions with the city’s infrastructure. From the spectacular architecture built to signify China’s neoliberal approaches to globalized urban spaces, to micro-modifications in how citizens sort their recycling depicted on neighborhood bulletin boards, the visuals of Chinese statecraft saturate the urban landscape of Beijing. I advocate for heterogeneous ways of seeing of infrastructure that releases its from being solely a function of statecraft, to a constitutive part of the artistic practices of: Song Dong (宋冬 b. -

World Bank Document

EA for Shanghai Hongkou District Liyang Road Old House Protection and Rehabilitation Project E541 V. 3 December 2002 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Assessment Report For Liyang Road Old House Protection and Rehabilitation Project Public Disclosure Authorized Hongkou district Shanghai (Certificate No.: GHPZHJZ 1810) Public Disclosure Authorized Shanghai Zhongfang Real Estates Exchange Company Ltd. Shanghai Bohong Engineering and Construction Company Ltd. SEPA-Tongji Research Institute of Environmental Protection Science &Technology Public Disclosure Authorized December, 2002 EA for Shanghai Hongkou District Liyang Road Old House Protection and Rehabilitation Project Environmental Impact Assessment Report For Liyang Road Old House Protection and Rehabilitation Project Hongkou district Shanghai Prepared by Shanghai Zhongfang Real Estates Exchange Company Ltd. Shanghai Bohong Engineering and Construction Company Ltd. SEPA-Tongj i Research Institute of Environmental Protection Science &Technology Responsible Person Shi Jian-min, Feng Cang, Dai Yi-rong Persons Involved in Preparation Shi Jian-min, Xu Cheng-zhong, Feng Cang, Dai Yi-rong, Xu Ming-de, Zhang Zhi-qiang, Lu Bin, Zhuan Yi-li Checked by Yang Hai-zhen, Xin Gong-fu December, 2002 EA for Shanghai Hongkou District Liyang Road Old House Protection and Rehabilitation Project CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 1 1.1 Assessment Origins ................................................................... 1 1.2 Assessment Basis ..................................................................