Course Preparation and Tracksetting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldry in the Republic of Macedonia (1991-2019)

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 1 September 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202109.0027.v1 Article Heraldry in the Republic of Macedonia (1991-2019) Jovan Jonovski1, * 1 Macedonian Heraldic Society; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +38970252989 Abstract: Every country has some specific heraldry. In this paper, we will consider heraldry in the Republic of Macedonia, understood by the multitude of coats of arms, and armorial knowledge and art. The paper covers the period from independence until the name change (1991-2019). It co- vers the state coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia especially the 2009 change. Special atten- tion is given to the development of the municipal heraldry, including the legal system covering the subject. Also personal heraldry developed in 21 century is considered. The paper covers the de- velopment of heraldry and the heraldic thought in the given period, including the role of the Macedonian Heraldic Society and its journal Macedonian Herald in development of theoretic and practical heraldry, as well as its Register of arms and the Macedonian Civic Heraldic System. Keywords: Heraldry in Macedonia; Macedonian civic heraldry; Republic of Macedonia. 1. Introduction The Republic of Macedonia became independent from the Socialist Federative Re- public of Yugoslavia with the Referendum of 8 September 1991. The Democratic Federal Macedonia was formed during the first session of the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the Na- tional Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) on 2 August 1944 (it later became the People’s Republic of Macedonia, a federal unit of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia). -

CHEVRONS Chevron (Insignia)

____________________________________________________ CHEVRONS Chevron (insignia) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chevron_%28insignia%29 Jump to: navigation, search "Argent a chevron gules" A chevron (also spelled cheveron, especially in older documents) is an inverted V-shaped pattern. The word is usually used in reference to a kind of fret in architecture, or to a badge or insignia used in military or police uniforms to indicate rank or length of service, or in heraldry and the designs of flags (see flag terminology). The symbol is also used on highway signs to guide drivers around curves. Ancient history The chevron occurs in early art including designs on pottery and rock carvings. Examples can be found approximately 1800 BC in archaeological recovery of pottery designs from the palace of Knossos on Crete in the modern day country of Greece.[1] Sparta (Lacedaemonia (Λακεδαιμονία)) used a capital lambda (Λ) on their shields. Heraldry A chevron is one of the ordinaries in heraldry, one of the simple geometrical figures which are the chief images in many arms. It can be subject to a number of modifications. When the ends are cut off in a way that looks like the splintered ends of a broken piece of wood, with an irregular zig-zag pattern, it is called éclaté.[2] When shown as a smaller size than standard, it is a diminutive called a chevronel. 1 ____________________________________________________ Chevrons appeared early in the history of heraldry, especially in Normandy. In Scandinavia the chevron is known as sparre; an early example appears in the arms of Arvid Gustavsson Sparre. -

City of Watsonville Historic Context Statement (2007)

Historic Context Statement for the City of Watsonville FINAL REPORT Watsonville, California April 2007 Prepared by One Sutter Street Suite 910 San Francisco CA 94104 415.362.7711 ph 415.391.9647 fx Acknowledgements The Historic Context Statement for the City of Watsonville would not have been possible without the coordinated efforts of the City of Watsonville Associate Planner Suzi Aratin, and local historians and volunteers Ann Jenkins and Jane Borg whose vast knowledge and appreciation of Watsonville is paramount. Their work was tireless and dependable, and their company more than pleasant. In addition to hours of research, fact checking and editing their joint effort has become a model for other communities developing a historic context statement. We would like to thank the City of Watsonville Council members and Planning Commission members for supporting the Historic Context Statement project. It is a testimony to their appreciation and protection of local history. Thanks to all of you. Table of Contents Chapter Page 1.0 Background and Objectives 1 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Location and Boundaries of Study 1.3 Context Statement Objective 2.0 Methodology 5 2.1 Context Statement Methodology 2.2 Summary of Resources 3.0 Introduction to Historic Contexts 7 3.1 Summary of Historic Contexts 3.2 Summary of Regional History Before Incorporation 3.3 Summary of regional history from 1868 – 1960 4.0 Historic Context 1 - Municipal Development 17 4.1 Overview 4.2 History 4.2.1 Schools 4.2.2 Civic Institutions 4.2.3 Infrastructure: Water 4.2.4 Infrastructure: -

Spokane Flag Redesign Official Voters Guide

Spokane Flag Redesign Official Voters Guide Welcome! The vote you are about to participate in reflects the culmination of almost two years’ work by ordinary Spokane citizens, City officials, and dozens of artists from around the country. Spokane’s current flag (show on the next page) has been a subject of mockery in vexillological (that’s a fancy word for the study of flags!) circles for years. However, it wasn’t until Spokane resident and now Flag Commission member Max Nesbitt presented a proposal to redesign the flag in early 2019 that the ball officially got rolling and gears began to turn. Spokane Councilmember Kate Burke took up Max’s call and proposed a resolution to form this Commission which passed that summer, and the Commission was formed that fall. Comprising voices of a multitude of perspectives, the Commission represents a cross section of Spokane –artists, students, politicians, civil servants and more. We considered an initial 400 designs and a public poll held in December 2020 narrowed it down to 100 semi-finalists. The Commission has selected these 12 finalists because we feel they reflect a diversity of styles and inspirations while falling within the guidelines we set out in our opening meetings. Happy voting! Spokane Flag Commission Joshua Hiler, Chair – Council Appointee, District 3 Max Nesbitt – Council Appointee, District 2 Corey Marcoux – Council Appointee, District 1 John Mujica – Council Appointee, At Large Matthew Budke – Mayoral Appointee Glenn Ford – Spokane Tribe Jeff Ferguson – Spokane Tribe Andrew Whitver – Spokane Arts Commission Scyla Dowd – Youth Appointee Kate Burke – City Council Betsy Wilkerson – City Council The Current Spokane Flag Adopted in 1975, this flag has seen little to no use since then. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

ICV20 Lupant.Pub

Emblems of the State of Katanga (1960-1963) Michel Lupant On June 30 1960 the Belgian Congo became the Republic of Congo. At that time Ka- tanga had 1,654,000 inhabitants, i.e. 12.5% of the population of the Congo. On July 4 the Congolese Public Force (in fact the Army) rebelled first in Lower-Congo, then in Leopoldville. On July 8 the mutiny reached Katanga and some Europeans were killed. The leaders of the rebels were strong supporters of Patrice Lumumba. Faced with that situation on July 11 1960 at 2130 (GMT), Mr. Tschombe, Ka- tanga’s President, delivered a speech on a local radio station. He reproached the Cen- tral government with its policies, specially the recruitment of executives from commu- nist countries. Because of the threats of Katanga submitting to the reign of the arbitrary and the communist sympathies of the central government, the Katangese Government decided to proclaim the independence of Katanga.1 At that time there was no Katan- gese flag. On July 13 President Kasa Vubu and Prime Minister Lumumba tried to land at Elisabethville airport but they were refused permission to do so. Consequently, they asked United Nations to put an end to the Belgian agression. On July 14 the Security Council of the United Nations adopted a resolution asking the Belgian troops to leave the Congo, and therefore Katanga. Mr. Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General, considered the United Nations forces had to enter Katanga. Mr. Tschombe opposed that interpreta- tion and affirmed that his decision would be executed by force it need be. -

Heraldry in Ireland

Heraldry in Ireland Celebrating 75 years of the Office of the Chief Herald at the NLI Sir John Ainsworth Shield Vert, a chevron between three battle-axes argent Crest A falcon rising proper, beaked, legged and belled gules Motto Surgo et resurgam Did you know? Sir John Ainsworth was the NLI's Surveyor of Records in Private Keeping in the 1940s and 1950s. Roderick More OFerrall Shield Quarterly: 1st, Vert, a lion rampant or (for O Ferrall); 2nd, Vert a lion rampant in chief three estoiles or (for O More); 3rd, Argent, upon a mount vert two lions rampant combatant gules supporting the trunk of an oak tree entwined with a serpent descending proper, (for O Reilly); 4th, Azure, a bend cotised or between six escallops argent (for Cruise) Crest On a ducal coronet or a greyhound springing sable; A dexter hand lying fess-ways proper cuffed or holding a sword in pale hilted of the second pierced through three gory heads of the first Motto Cú re bu; Spes mea Deus Did you know? This four designs on the shield represent four families. Heiress Leticia More of Balyna, county Kildare married Richard Ferrall in 1751. Their grandson Charles Edward More O'Ferrall married Susan O'Reilly in 1849. Susan was the daughter of Dominic O'Reilly of Kildangan Castle, county Kildare who had married heiress Susanna Cruise in 1818. Dublin Stock Exchange Shield Quarterly: 1st, Sable, a tower or; 2nd, Vert, three swords points upwards two and one proper pommelled and hilted or; 3rd, Vert, three anchors erect two and one argent; 4th, Chequy, sable and argent, on a chief argent an escroll proper, inscribed thereon the words Geo. -

Global Storage Resource Assessment – 2019 Update 10365GLOB-Rep-01-01 June 2020

9 Global Storage Resource Assessment – 2019 Update 10365GLOB-Rep-01-01 June 2020 www.pale-blu.com Support by: 2020 Global Storage Resource Assessment – 2019 Update Contents Contents Document Summary Client Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) Project Title 10365GLOB Title: Global Storage Resource Assessment – 2019 Update Distribution: Classification: Client Confidential Date of Issue: 22nd June 2020 Prepared by: Shelagh Baines, Elle Lashko Approved by: Alan James Amendment Record Rev Date Description Issued By Checked By Approved By V00 30-04-20 Draft S Baines / E Lashko R Gilbert A James Amended to include V01 22-06-20 S Baines / E Lashko R Gilbert A James comments from OGCI SWG Disclaimer: While the information contained in this document is believed to be accurate at the time of printing, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by Pale Blue Dot Energy Limited (“PBD”) or any of its respective affiliates or any of PBD’s or it’s respective affiliate’s directors, officers or employees or any other person whatsoever on the completeness, accuracy or fairness of the information contained in this document, nor is any responsibility accepted for any errors, misstatements in, or omissions from, this document or any direct or consequential loss howsoever arising from any use of, or reliance on, this document or otherwise in connection with it. No responsibility or liability is accepted for any loss, cost or damage suffered or incurred as a result of reliance on any such information, opinions or beliefs. Where third-party information has been used in this document, PBD has not independently verified such information and PBD does not represent or warrant that this information is accurate. -

Storm Report-Irma-PM-FL GA.XLS

Brand Name Site Name Street Address City State Zip Phone# EXXONMOB BOB'S FUEL 16091 NW US HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 32615 (386) 462-5590 BP BP 8997157 15980 NW HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 326150000 (386) 462-0539 CHVRNWF CHEVRON 0042065 15000 NW US HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 326155666 (000) 000-0000 SHELL CIRCLE K STORE 27239 16070 NW US HIGHWAY ALACHUA FL 326154890 (000) 000-0000 EXXONMOB CK 2721202 14411 N.W. US HIGHWA ALACHUA FL 32615 (386) 462-2880 RACEWAY RACEWAY 6953 16171 NW US HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 32616 (770) 431-7600 SUNOCO SUNOCO SRVC STATION11921 NW US HWY ALACHUA FL 326530000 (386) 462-1301 RACETRAC RACETRAC 629 484 SOUTH & SR434 ALTAMONTE SP FL 32714 (407) 862-2242 SHELL CIRCLE K STORES INC 91 W STATE ROUTE 436 ALTAMONTE SPG FL 327144206 (407) 788-8186 SUNOCO SUNOCO SRVC STATION1395 E. ALTAMONT ALTAMONTE SPG FL 329010000 (407) 834-1018 WAWA WAWA 5179 919 WEST SR 436 ALTAMONTE SPRING FL 327142931 (610) 358-8000 7-ELEVEN 7-ELEVEN 10060 401 WEST HWY 436 ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32714 (407) 862-5671 7-ELEVEN 7-ELEVEN 23348 340 DOUGLAS AVE ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32714 (407) 788-1947 7-ELEVEN 7-ELEVEN 30059 898 SR 434 NORTH ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32714 (407) 869-1291 EXXONMOB 7-ELEVEN 34767 901 W HWY #436 ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 327142901 (407) 682-5912 EXXONMOB 7-ELEVEN 34780 501 E ALTAMONTE DR ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 327014702 (407) 331-4366 BP BP 9493347 109 E ALTAMONTE DR ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 327014310 (407) 260-0144 UNBRANDED CASSELBERRY 66 FOOD1681 S RONALD REAGANALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32701 (407) 831-5844 CHVRNWF CHEVRON 0301815 201 W. -

United States Flag Privately-Owned Merchant Fleet

U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime Administration ‐ Office of Policy and Plans 02/04/2019 United States Flag Privately‐Owned Merchant Fleet Oceangoing, Self‐Propelled, Vessels of 1,000 Gross Tons and Above that Carry Cargo from Port to Port Summary of Changes from 2016 Onward e r e g e g n t r e l n a i p o e e a me u t s mb y T g P A a a A Ch T B U n u T S S A r T Ch W I f N G r J l a N i p V o l i D a M V e pe e O h e M Ch p e s O t S Y y s a M T I e D V IN Jan‐16 9680853 PERLA DEL CARIBE Container ship 36912 45000 2016 Totem Ocean Trailer Express N N N Y Y Vessel flagged into U.S. Flag Fleet IN Jan‐16 9448334 SLNC GOODWILL Tanker 30241 50326 2009 Nord Goodwill LLC NNNNY Vessel flagged into U.S. Flag Fleet Vessel Operator changed from Handytankers K/S OPERATOR Jan‐16 9255244 MAERSK MICHIGAN Tanker 28517 47047 2003 Maersk Line A/S NNY NY to Maersk Line A/S OUT Feb‐16 8919922 COURAGE Ro‐Ro 52288 29213 1991 American Roll‐On Roll‐Off Y Y N N Y Vessel flagged out of U.S. Flag Fleet IN Feb‐16 9782493 COASTAL STANDARD General Cargo 2451 2565 2016 Coastal Transportation Inc. N N N Y Y Vessel flagged into U.S. -

Oil and Water Don't

Oil and Water Don’t Mix – Keeping Canada’s West Coast Oil-Free – By Stuart Hertzog March 2003 Table of Contents Preface..........................................................................................................................4 Overview.......................................................................................................................6 1 The West Coast Marine Ecosystem......................................................................9 2 Four Phases of Exploitation................................................................................15 Exploration .............................................................................................................15 Development ..........................................................................................................18 Production ..............................................................................................................19 Decommissioning...................................................................................................22 3 Potential Disasters...............................................................................................23 Blowouts and Spills ................................................................................................23 Wind and Waves ....................................................................................................30 Earthquakes and Tsunamis ...................................................................................32 Ongoing Pollution...................................................................................................35 -

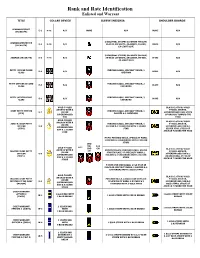

Rank and Rate Identification Enlisted and Warrant

Rank and Rate Identification Enlisted and Warrant TITLE COLLAR DEVICE SLEEVE INSIGNIA SHOULDER BOARDS SEAMAN RECRUIT E-1 NONE N/A NONE N/A NONE N/A (SR/AR/FR) 2 DIAGONAL STRIPES SA-WHITE ON BLUE, SEAMAN APPRENTICE E-2 NONE N/A SA-BLUE ON WHITE, AA-GREEN, FA-RED, NONE N/A (SA/AA/FA) CA-LIGHT BLUE 3 DIAGONAL STRIPES SN-WHITE ON BLUE, SEAMAN (SN/AN/FN) E-3 NONE N/A SN-BLUE ON WHITE, AN-GREEN, FN-RED, NONE N/A CN-LIGHT BLUE PETTY OFFICER THIRD PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 E-4 N/A NONE N/A CLASS CHEVRON PETTY OFFICER SECOND PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 2 E-5 N/A NONE N/A CLASS CHEVRONS PETTY OFFICER FIRST PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 3 E-6 N/A NONE N/A CLASS CHEVRONS GOLD FOULED BLACK CLOTH W/ GOLD ANCHOR WITH A FOULED ANCHOR, CHIEF PETTY OFFICER PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 E-7 SILVER SUPERIMPOSED USN, STOCK (CPO) ROCKER & 3 CHEVRONS SUPERIMPOSED OF ANCHOR TOWARD THE USN HEAD GOLD FOULED BLACK CLOTH W/ GOLD ANCHOR WITH A SENIOR CHIEF PETTY PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 FOULED ANCHOR, SILVER OFFICER E-8 ROCKER & 3 CHEVRONS WITH 1 SILVER SUPERIMPOSED USN & 1 SUPERIMPOSED (SCPO) STAR SILVER STAR, STOCK OF USN & 1 SILVER ANCHOR TOWARD THE HEAD STAR MCPO: PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 ROCKER & 3 CHEVERONS WITH 2 SILVER STARS CMD CM/ FOR GOLD FOULED MCPO CNO CM BLACK CLOTH W/ GOLD ANCHOR WITH A CMDCM/CNOCM: PERCHED EAGLE, SILVER MASTER CHIEF PETTY CM FOULED ANCHOR, SILVER STAR IN PLACE OF SPECIALTY MARK, 1 OFFICER E-9 SUPERIMPOSED USN & 2 SUPERIMPOSED ROCKER & 3 CHEVERONS WITH 2 SILVER (MCPO) SILVER STARS, STOCK OF USN & 2 SILVER