Dreadful Fashionable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Studying Craft: Trends in Craft Education and Training Participation in Contemporary Craft Education and Training

Studying craft: trends in craft education and training Participation in contemporary craft education and training Cover Photography Credits: Clockwise from the top: Glassmaker Michael Ruh in his studio, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian Head of Art Andrew Pearson teaches pupils at Christ the King Catholic Maths and Computing College, Preston Cluster, Firing Up, Year One. © University of Central Lancashire. Silversmith Ndidi Ekubia in her studio at Cockpit Arts, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian ii ii Participation in contemporary craft education and training Contents 1. GLOSSARY 3 2. FOREWORD 4 3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 3.1 INTRODUCTION 5 3.2 THE OFFER AND TAKE-UP 5 3.3 GENDER 10 3.4 KEY ISSUES 10 3.5 NEXT STEPS 11 4. INTRODUCTION 12 4.1 SCOPE 13 4.2 DEFINITIONS 13 4.3 APPROACH 14 5. POLICY TIMELINE 16 6. CRAFT EDUCATION AND TRAINING: PROVISION AND PARTICIPATION 17 6.1 14–16 YEARS: KEY STAGE 4 17 6.2 16–18 YEARS: KEY STAGE 5 / FE 22 6.3 ADULTS: GENERAL FE 30 6.4 ADULTS: EMPLOYER-RELATED FE 35 6.5 APPRENTICESHIPS 37 6.6 HIGHER EDUCATION 39 6.7 COMMUNITY LEARNING 52 7. CONCLUDING REMARKS 56 8. APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY 57 9. NOTES 61 1 Participation in contemporary craft education and training The Crafts Council is the national development agency for contemporary craft. Our goal is to make the UK the best place to make, see, collect and learn about contemporary craft. www.craftscouncil.org.uk TBR is an economic development and research consultancy with niche skills in understanding the dynamics of local, regional and national economies, sectors, clusters and markets. -

Recipes Your Best Pies 39 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Swings 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Taking in Tyler by Melissa Gaskill

LOCAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE EDITION APRIL 2016 Helping Local Libraries Gettysburg Casualty Best Pies. Yum! HATSON! Texas hatmakers have you covered We’re e on a mission to set the neighborhood standard. With the most dependable equipment, we create spectacular spaces. We thrive on the fresh air, the challenge and the results of our efforts. We set the bar high to create a space we’re proud to call our own. kubota.com © Kubota Tractorr Corpporation, 2016 Since 1944 April 2016 FAVORITES 5 Letters 6 Currents 20 Local Co-op News Get the latest information plus energy and safety tips from your cooperative. 33 Texas History Gettysburg’s Last Casualty By E.R. Bills 35 Recipes Your Best Pies 39 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Swings 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Taking in Tyler By Melissa Gaskill Jeff Biggars applies steam ONLINE as he shapes a hat. TexasCoopPower.com Find these stories online if they don’t FEATURES appear in your edition of the magazine. Observations Cowboy Hatters Texas artisans crown your cranium in Tough Kid, Tough Breaks 8 a grand and storied tradition By Clay Coppedge Story by Gene Fowler | Photos by Tadd Myers Texas USA The Erudite Ranger Community Anchors Enlivening libraries establishes By Lonn Taylor 12 an environment for learning, sharing and loving literacy By Dan Oko NEXT MONTH New Directions in Farming A younger generation seeks alternatives to keep the family business thriving. 33 39 35 42 BIGGARS: TADD MYERS. PLANT: CANDY1812 | DOLLAR PHOTO CLUB ON THE COVER J.W. Brooks handcrafts hats for cowboys and cowgirls at his shop in Lipan. -

The Milliner Cross Stitch Pattern by Perrette Samouiloff

The Milliner cross stitch pattern by Perrette Samouiloff Manufacturer: Perrette Samouiloff Reference:PER239 Price: $11.99 Options: download pdf file : English Description: The Milliner CROSS STITCH PATTERN READY TO DOWNLOAD, DESIGNED BY Perrette Samouiloff This design is part of a series of cross stitch charts related to needlecrafts. After the Lacemaker, here is a tribute to the fine art of hatmaking. The milliner's trade, which has almost disappeared today, is the art of designing, making, decorating and personalizing hats, fashion accessories par excellence. In this cross stitch pattern, the milliner is at work, needle in hand, in her hat shop, while her customers try various hats on. The hats come in a wide variety of styles and very feminine shapes: wide brim and veil, cloche hats from the thirties, floppy brimmed hats, round caps, straw hats, together with a whole collection of exquisite small hat pins. The title of the embroidery "The Milliner" is embroidered in pretty cursive letters. The design is an adaptation from the French "La Modiste". If you would rather stitch the French version, please contact us after placing the order and we will send you the chart with the original French text (last picture). A cross stitch pattern by Perrette Samouiloff. >> see more patterns related to Fashion and Costumes by Perrette Samouiloff Chart info & Needlework supplies for the pattern: The Milliner Chart size in stitches: 138 x 160(wide x high) Needlework fabric: Aida, Linen or Evenweave, white >> View size in my choice of fabric (fabric calculator) Stitches: Cross stitch, Backstitch, 3/4 cross stitch Chart: Black & White, color detail Threads: DMC Number of colors:1 Themes: hat making workshop, hat shop, fashion, ornamental hat pins >> see all patterns related to Clothes and Fashion accessories (all designers) All patterns on Creative Poppy's website are printable and available for instant download. -

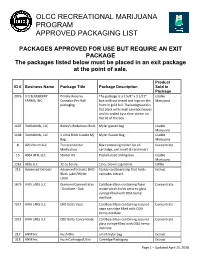

Olcc Recreational Marijuana Program Approved Packaging List

OLCC RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA PROGRAM APPROVED PACKAGING LIST PACKAGES APPROVED FOR USE BUT REQUIRE AN EXIT PACKAGE The packages listed below must be placed in an exit package at the point of sale. Product ID # Business Name Package Title Package Description Sold in Package 2076 3 D BLUEBERRY Private Reserve The package is a 2 5/8" x 3 1/12" Usable FARMS, INC. Cannabis Pre-Roll box with our brand and logo on the Marijuana packaging front in gold foil. The background is flat black with small cannabis leaves and its sealed by a clear sticker on the lid of the box. 1107 3Littlebirds, LLC Bobby's Bodacious Buds Mylar gusset bag Usable Marijuana 1108 3Littlebirds, LLC 3 Little Birds Usable Mj Mylar Gusset Bag Usable Bag Marijuana 8 420 Pharm LLC Transcendental Box containing holder for oil Concentrate Medication cartridge, cart inself & card insert 15 4964 BFH, LLC Starter Kit Pocket-sized sliding box. Usable Marijuana 1262 Ablis LLC 12 oz bottle 12 oz crown cap bottle Edible 213 Advanced Extracts Advanced Extracts BHO Sturdy cardboard slip that holds Extract Black Label/White cannabis extract. Label. 1679 AIRA LABS LLC Diamond Concentrates Cardboard box containing foam Concentrate - Distillate - Dab matte which holds secured glass syringe filled with ODA hemp distillate 1921 AIRA LABS LLC CBD Delta Vape Cardboard box containing secured Concentrate vape cartridge filled with ODA hemp distillate 1922 AIRA LABS LLC CBD Delta Concentrate Cardboard box containing secured Concentrate glass syringe filled with ODA hemp distillate 217 ANM Inc. Hush Bho small mylar bag Extract 218 ANM Inc. -

Vital Signs the Intersection of Health & Community Development

Vital Signs The Intersection of Health & Community Development Tweet @phillycdcs Join the Movement Towards An Equitable Philadelphia PACDC Community Development Leadership Institute’s 2019 FORWARD EQUITABLE DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE Wednesday, June 26th & Thursday June 27th, 2019 KEYNOTE SPEAKER Liz Ogbu A designer, urbanist, and social innovator, Liz is an expert on social and spatial innovation in challenged urban environments Philadelphia globally. Through her multidisciplinary design and innovation consultancy, Studio O, she collaborates with/in communities in need does Better to leverage the power of design to catalyze sustained social impact. Among her honors, when we ALL she is a TED speaker, one of Public Interest Design’s Top 100, and a former Aspen Ideas do Better Scholar. “What if gentrification was about healing communities instead of displacing them?” —Liz Ogbu PHOTO CREDIT: RYAN LASH PHOTOGRAPHY Join 300 community developers, small business entrepreneurs, health practitioners, researchers, artists, educators, and activists committed to working toward a more equitable Philadelphia. Conference attendees will explore innovative pathways to ensuring all Philadelphia’s residents and businesses prosper, network with others striving to undertake equitable development, and be uplifted and energized through moving stories of success and lessons learned. Keynote and workshops on Wednesday, June 26th, and in-depth learning seminars on Thursday, June 27th. CONFERENCE SPONSOR PARTNERS: Jefferson Center for Urban Health/Jefferson Health Systems, -

Color Front Cover

COLOR FRONT COVER COLOR CGOTH IS I COLOR CGOTH IS II COLOR CONCERT SERIES Welcome to our 18th Season! In this catalog you will find a year's worth of activities that will enrich your life. Common Ground on the Hill is a traditional, roots-based music and arts organization founded in 1994, offering quality learning experiences with master musicians, artists, dancers, writers, filmmakers and educators while exploring cultural diversity in search of a common ground among ethnic, gender, age, and racial groups. The Baltimore Sun has compared Common Ground on the Hill to the Chautauqua and Lyceum movements, precursors to this exciting program. Our world is one of immense diversity. As we explore and celebrate this diversity, we find that what we have in common with one another far outweighs our differences. Our common ground is our humanity, often best expressed by artistic traditions that have enriched human experience through the ages. We invite you to join us in searching for common ground as we assemble around the belief that we can improve ourselves and our world by searching for the common ground in one another, through our artistic traditions. In a world filled with divisive, negative news, we seek to discover, create and celebrate good news. How we have grown! Common Ground on the Hill is a multifaceted year-round program, including two separate Traditions Weeks of summer classes, concerts and activities, held on the campus of McDaniel College, two separate Music and Arts festivals held at the Carroll County Farm Museum, two seven-event Monthly Concert Series held in Westminster and Baltimore, and a new program this summer at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Common Ground on Seminary Ridge. -

Tela Ecólogica Textile Traditions + Eco-Tourism in Yucatán --- 2017 International Textile + Apparel Association Study Tour

Tela Ecólogica Textile Traditions + Eco-Tourism in Yucatán --- 2017 International Textile + Apparel Association Study Tour --- Date December 9-20, 2017 Duration 12 days Cost $2,500 USD per person OVERVIEW Tela Ecólogica is a textile-focused cultural and creative immersion experience into the world of Mexican artisanship, craft processes and design. This study opportunity offers exposure to new cultural environments and insight into the world of artisan production as it applies to the Yucatán region and its people. It will foster a deeper understanding of the impacts of globalization on Mayan culture, and the significance of environmental stewardship and social justice through the lens of cultural textiles and craft. Yucatán is wonderfully rich with the cultural context of language, food, and visual aesthetics. Participants will experience travel in the region from a range of different vantage points- from tourist resorts, historic boutique hotels to thatched roof huts. We will stay in haciendas, swim in cenotes, and visit ancient Maya ruins. We will tour the popular cities of Cancun, Tulum and Playa del Carmen, and visit the lesser-travelled cities of Merida and Valladolid, and experience many charming pueblos along the way. Participants will get a rarely-seen glimpse of authentic textile design and craft making throughout the the Yucatán peninsula region, experiencing the beauty of Mexican culture as we tour marketplaces, textile factories, ateliers, boutiques, artist studios, designer workshops, artisan homes and museums. We will learn regional handcraft skills from indigenous Mayan artisans and designers- exploring henequen fiber processing, back-strap loom weaving, hand and machine embroidery, cross-stitch, crochet and natural dyeing, completing our own sample works along the way. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

Friesian Division Must Be Members of IFSHA Or Pay to IFSHA a Non Member Fee for Each Competition in Which Competing

CHAPTER FR FRIESIAN AND PART BRED FRIESIAN SUBCHAPTER FR1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS FR101 Eligibility to Compete FR102 Falls FR103 Shoeing and Hoof Specifications FR104 Conformation for all horses SUBCHAPTER FR-2 IN-HAND FR105 Purebred Friesian FR106 Part Bred Friesian FR107 General FR108 Tack FR109 Attire FR110 Judging Criteria for In-Hand and Specialty In-Hand Classes FR111 Class Specifications for In-Hand and Specialty In-Hand classes FR112 Presentation for In-Hand Classes FR113 Get of Sire and Produce of Dam (Specialty In-Hand Classes) FR114 Friesian Baroque In-Hand FR115 Dressage and Sport Horse In-Hand FR116 Judging Criteria FR117 Class Specifications FR118 Championships SUBCHAPTER FR-3 PARK HORSE FR119 General FR120 Qualifying Gaits FR121 Tack FR122 Attire FR123 Judging Criteria SUBCHAPTER FR-4 ENGLISH PLEASURE SADDLE SEAT FR124 General FR125 Qualifying Gaits FR126 Tack FR127 Attire FR128 Judging Criteria SUBCHAPTER FR-5 COUNTRY ENGLISH PLEASURE- SADDLE SEAT FR129 General FR130 Tack FR131 Attire © USEF 2021 FR - 1 FR132 Qualifying Gaits FR133 Friesian Country English Pleasure Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER FR-6 ENGLISH PLEASURE—HUNT SEAT FR134 General FR135 Tack FR136 Attire FR137 Qualifying Gaits FR138 English Pleasure - Hunt Seat Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER FR-7 DRESSAGE FR139 General SUBCHAPTER FR-8 DRESSAGE HACK FR140 General FR141 Tack FR142 Attire FR143 Qualifying Gaits and Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER FR-9 DRESSAGE SUITABILITY FR144 General FR145 Tack FR146 Attire FR147 Qualifying Gaits and Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER -

Text &Textile Text & Textile

1 TextText && TextileTextile 2 1 Text & Textile Kathryn James Curator of Early Modern Books & Manuscripts and the Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Melina Moe Research Affiliate, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Katie Trumpener Emily Sanford Professor of Comparative Literature and English, Yale University 3 May–12 August 2018 Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Yale University 4 Contents 7 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction Kathryn James 13 Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs, & the Finest Thread Melina Moe 31 Threads of Life: Textile Rituals & Independent Embroidery Katie Trumpener 51 A Thin Thread Kathryn James 63 Notes 67 Exhibition Checklist Fig. 1. Fabric sample (detail) from Die Indigosole auf dem Gebiete der Zeugdruckerei (Germany: IG Farben, between 1930 and 1939[?]). 2017 +304 6 Acknowledgments Then Pelle went to his other grandmother and said, Our thanks go to our colleagues in Yale “Granny dear, could you please spin this wool into University Library’s Special Collections yarn for me?” Conservation Department, who bring such Elsa Beskow, Pelle’s New Suit (1912) expertise and care to their work and from whom we learn so much. Particular thanks Like Pelle’s new suit, this exhibition is the work are due to Marie-France Lemay, Frances of many people. We would like to acknowl- Osugi, and Paula Zyats. We would like to edge the contributions of the many institu- thank the staff of the Beinecke’s Access tions and individuals who made Text and Textile Services Department and Digital Services possible. The Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Unit, and in particular Bob Halloran, Rebecca Center for British Art, and Manuscripts and Hirsch, and John Monahan, who so graciously Archives Department of the Yale University undertook the tremendous amount of work Library generously allowed us to borrow from that this exhibition required. -

(A) Machinery, Plant, Vehicles ; (B) Construction of Buildings ; Basic Data on the Essential Characteristics of Industry Were Co

Official Journal of the European Communities 201 13.8.64 OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES 2193/64 COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 30 July 1964 concerning co-ordinated annual surveys of investment in industry ( 64/475/EEC ) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC Article 2 COMMUNITY, For the purposes of this Directive, an industry shall Having regard to the Treaty establishing the Euro be defined by reference to the 'Nomenclature of Indus pean Economic Community, and in particular Article tries in the European Communities' ( NICE). 1 In the 213 thereof ; case of small undertakings the survey may be carried out by random sampling. Having regard to the draft submitted by the Com Article 3 Whereas in order to carry out the tasks entrusted to it under the Treaty the Commission must have at its The figures to be recorded shall be those in respect disposal annual statistics on the trend of investment of annual investment expenditure ( including plant in the industries of the Community ; constructed by the undertakings themselves), broken Whereas in the industrial survey for 1962 comparable down as follows : basic data on the essential characteristics of industry ( a ) Machinery, plant, vehicles ; were collected for the first time ; whereas such a ( b) Construction of buildings ; census cannot be carried out frequently ; whereas annual statistics concerning certain basic matters ( c) Purchase of existing buildings and of land . cannot however be dispensed with for the intervening Investments of a social nature shall , where possible, be years