Clinical Manifestations of Aural Fullness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definitions and Background

1 Definitions and Background Tinnitus is a surprisingly complex subject. Numer- ears.” And, in fact, the word “tinnitus” is derived ous books would be required to adequately cover the from the Latin word tinniere, which means “to current body of knowledge. The present handbook ring.” Patients report many different sounds—not focuses on describing procedures for providing just ringing—when describing the sound of their clinical services for tinnitus using the methodology tinnitus, as we discuss later in this chapter. of progressive tinnitus management (PTM). In this opening chapter we establish common ground with respect to terminology and contextual Transient Ear Noise information. Relevant definitions are provided, many of which are operational due to lack of consensus It seems that almost everyone experiences “tran- in the field. Additional background information sient ear noise,” which typically is described as a includes brief descriptions of epidemiologic data, sudden whistling sound accompanied by the per- patient data, and conditions related to reduced tol- ception of hearing loss (Kiang, Moxon, & Levine, erance (hypersensitivity) to sound. 1970). No systematic studies have been published to date describing the prevalence and properties of transient ear noise; thus, anything known about Basic Concepts and Terminology this phenomenon is anecdotal. The transient auditory event is unilateral and seems to occur completely at random without any- Tinnitus is the experience of perceiving sound that thing precipitating the sudden onset of symptoms. is not produced by a source outside of the body. The Often the ear feels blocked during the episode. The “phantom” auditory perception is generated some- symptoms generally dissipate within a period of where in the auditory pathways or in the head or about a minute. -

153 Alcohol Intake, 47, 48 Aminoglycoside Antibiotics, 5

Index A Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), 41–42 Tinnitus Problem Checklist, 44–45 Alcohol intake, 47, 48 Audiology, 24 Aminoglycoside antibiotics, 5 Individualized Support protocol, 77–79 Amitryptiline, 48 patient education, 26 Amphetamine abuse, 47 triage to, 37 Antidepressants, 48 Auditory imagery, 4 Anxiety, 47, 48, 69 Anxiolitics, 48 B Appendixes. See Forms Aspirin, 5, 48 Bipolar disorder, 47 Assessment. See also Audiologic Evaluation; Interdisciplinary Evaluation C mental health, 67–70 psychoacoustic, 72–73 Caffeine intake, 5, 48 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 47 Case studies/patient examples Attention Scale, 61, 129–130 bilateral intermittent tinnitus, 32–33 Audiologic Evaluation bothersome tinnitus, 33 auditory function assessment, 42–43 CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy), 81 and candidacy for Group Education, 40 hearing loss/tinnitus, 32 Ear-Level Instrument Assessment/Fitting Individualized Support, 81 Flowchart, 45, 113 phonophobia, 33 hearing aid evaluation, 45–47 (See also Hearing PTSD, 33 aids main entry) sensorineural hearing loss, 41 Hearing Aid Special Considerations, 46, 115 CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy) Hearing Handicap Inventory, 42 case study, 81 and hyperacusis, 40, 41 clues for tinnitus management, 3 LDLs, 53 extended support option, 81–82 and mental health referral, 47 Group Education, 63–66 (See also Group Education objectives overview, 39, 99 main entry) otolaryngology exam need assessment, 43 Individualized Support, 80–81, 82 otoscopy, 42 and individualized support level, 30 overview, 27, 49 and patient education, 25, 31 patient example: sensorineural hearing loss, 41 in PTM foundational research, 17, 18–19 procedures overview, 39, 99 and STEM, 29, 55 pure-tone threshold evaluation, 42–43 telephone-based, 18 sleep disorder referral assessment, 47–48 CD/DVD: Managing Your Tinnitus, 151–152 somatosounds assessment, 43–44 Changing Thoughts and Feelings Worksheet, 64 suprathreshold audiometric testing, 43 Chemotherapy, 5, 48 THI (Tinnitus Handicap Inventory), 41–42, 105– Chronic tinnitus, 2. -

List of Phobias: Beaten by a Rod Or Instrument of Punishment, Or of # Being Severely Criticized — Rhabdophobia

Beards — Pogonophobia. List of Phobias: Beaten by a rod or instrument of punishment, or of # being severely criticized — Rhabdophobia. Beautiful women — Caligynephobia. 13, number — Triskadekaphobia. Beds or going to bed — Clinophobia. 8, number — Octophobia. Bees — Apiphobia or Melissophobia. Bicycles — Cyclophobia. A Birds — Ornithophobia. Abuse, sexual — Contreltophobia. Black — Melanophobia. Accidents — Dystychiphobia. Blindness in a visual field — Scotomaphobia. Air — Anemophobia. Blood — Hemophobia, Hemaphobia or Air swallowing — Aerophobia. Hematophobia. Airborne noxious substances — Aerophobia. Blushing or the color red — Erythrophobia, Airsickness — Aeronausiphobia. Erytophobia or Ereuthophobia. Alcohol — Methyphobia or Potophobia. Body odors — Osmophobia or Osphresiophobia. Alone, being — Autophobia or Monophobia. Body, things to the left side of the body — Alone, being or solitude — Isolophobia. Levophobia. Amnesia — Amnesiphobia. Body, things to the right side of the body — Anger — Angrophobia or Cholerophobia. Dextrophobia. Angina — Anginophobia. Bogeyman or bogies — Bogyphobia. Animals — Zoophobia. Bolsheviks — Bolshephobia. Animals, skins of or fur — Doraphobia. Books — Bibliophobia. Animals, wild — Agrizoophobia. Bound or tied up — Merinthophobia. Ants — Myrmecophobia. Bowel movements, painful — Defecaloesiophobia. Anything new — Neophobia. Brain disease — Meningitophobia. Asymmetrical things — Asymmetriphobia Bridges or of crossing them — Gephyrophobia. Atomic Explosions — Atomosophobia. Buildings, being close to high -

Tinnitus: Ringing in the SYMPTOMS Ears

Tinnitus: Ringing in the SYMPTOMS Ears By Vestibular Disorders Association TINNITUS WHAT IS TINNITUS? An abnormal noise perceived in one or both Tinnitus is abnormal noise perceived in one or both ears or in the head. ears or in the head. It Tinnitus (pronounced either “TIN-uh-tus” or “tin-NY-tus”) may be can be experienced as a intermittent, or it might appear as a constant or continuous sound. It can ringing, hissing, whistling, be experienced as a ringing, hissing, whistling, buzzing, or clicking sound buzzing, or clicking sound and can vary in pitch from a low roar to a high squeal. and can vary in pitch. Tinnitus is very common. Most studies indicate the prevalence in adults as falling within the range of 10% to 15%, with a greater prevalence at higher ages, through the sixth or seventh decade of life. 1 Gender distinctions ARTICLE are not consistently reported across studies, but tinnitus prevalence is significantly higher in pregnant than non-pregnant women. 2 The most common form of tinnitus is subjective tinnitus, which is noise that other people cannot hear. Objective tinnitus can be heard by an examiner positioned close to the ear. This is a rare form of tinnitus, 068 occurring in less than 1% of cases. 3 Chronic tinnitus can be annoying, intrusive, and in some cases devastating to a person’s life. Up to 25% of those with chronic tinnitus find it severe DID THIS ARTICLE enough to seek treatment. 4 It can interfere with a person’s ability to hear, HELP YOU? work, and perform daily activities. -

List of Phobias and Simple Cures.Pdf

Phobia This article is about the clinical psychology. For other uses, see Phobia (disambiguation). A phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, Phóbos, meaning "fear" or "morbid fear") is, when used in the context of clinical psychology, a type of anxiety disorder, usually defined as a persistent fear of an object or situation in which the sufferer commits to great lengths in avoiding, typically disproportional to the actual danger posed, often being recognized as irrational. In the event the phobia cannot be avoided entirely the sufferer will endure the situation or object with marked distress and significant interference in social or occupational activities.[1] The terms distress and impairment as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) should also take into account the context of the sufferer's environment if attempting a diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR states that if a phobic stimulus, whether it be an object or a social situation, is absent entirely in an environment - a diagnosis cannot be made. An example of this situation would be an individual who has a fear of mice (Suriphobia) but lives in an area devoid of mice. Even though the concept of mice causes marked distress and impairment within the individual, because the individual does not encounter mice in the environment no actual distress or impairment is ever experienced. Proximity and the degree to which escape from the phobic stimulus should also be considered. As the sufferer approaches a phobic stimulus, anxiety levels increase (e.g. as one gets closer to a snake, fear increases in ophidiophobia), and the degree to which escape of the phobic stimulus is limited and has the effect of varying the intensity of fear in instances such as riding an elevator (e.g. -

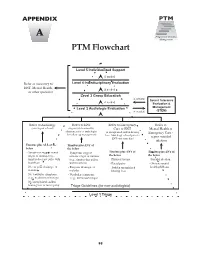

PTM Flowchart

APPENDIX A PTM Flowchart Level 5 Individualized Support if needed Refer as necessary to Level 4 Interdisciplinary Evaluation ENT, Mental Health, if needed or other specialist Level 3 Group Education if needed Sound Tolerance if needed Evaluation & Level 2 Audiologic Evaluation Management if needed (STEM) Refer to Audiology Refer to ENT Refer to Emergency Refer to (non-urgent referral) (urgency determined by Care or ENT Mental Health or clinician; refer to audiologist (if unexplained sudden hearing Emergency Care - for follow-up management) loss: Audiology referral prior to report suicidal ENT visit same day) ideation Tinnitus plus ALL of the Tinnitus plus ANY of below the below - Symptoms suggest neural - Symptoms suggest Tinnitus plus ANY of Tinnitus plus ANY of origin of tinnitus (e.g., somatic origin of tinnitus the below the below tinnitus does not pulse with (e.g., tinnitus that pulses - Physical trauma - Suicidal ideation heartbeat) with heartbeat) - Facial palsy - Obvious mental - No ear pain, drainage, or - Ear pain, drainage, or - Sudden unexplained health problems malodor malodor hearing loss - No vestibular symptoms - Vestibular symptoms (e.g., no dizziness/vertigo) (e.g., dizziness/vertigo) - No unexplained sudden hearing loss or facial palsy Triage Guidelines (for non-audiologists) Level 1 Triage 95 APPENDIX B Tinnitus Triage Guidelines (My Patient Complains About Tinnitus— What Should I Do?) Tinnitus (“ringing in the ears”) is experienced by lines for triaging the patient who complains about 10 to 15% of the adult population. Of those, about tinnitus. Note that many symptoms that might be one out of every five requires some degree of reported by patients are not included. -

Tinnitus Ringing in the Ears

PO BOX 13305 · PORTLAND, OR 97213 · FAX: (503) 229-8064 · (800) 837-8428 · [email protected] · WWW.VESTIBULAR.ORG Tinnitus: Ringing in the Ears An Overview By the Vestibular Disorders Association What is tinnitus? to seek treatment.4 It can interfere with a Tinnitus is abnormal noise perceived in person’s ability to hear, work, and one or both ears or in the head. Tinnitus perform daily activities. One study (pronounced either “TIN-uh-tus” or “tin- showed that 33% of persons being NY-tus”) may be intermittent, or it might treated for tinnitus reported that it appear as a constant or continuous disrupted their sleep, with a greater sound. It can be experienced as a ringing, degree of disruption directly related to hissing, whistling, buzzing, or clicking the perceived loudness or severity of the sound and can vary in pitch from a low tinnitus.5,6 roar to a high squeal. Causes and related factors Tinnitus is very common. Most studies Most tinnitus is associated with damage indicate the prevalence in adults as falling to the auditory (hearing) system, within the range of 10% to 15%, with a although it can also be associated with greater prevalence at higher ages, other events or factors: jaw, head, or through the sixth or seventh decade of neck injury; exposure to certain drugs; life.1 Gender distinctions are not nerve damage; or vascular (blood-flow) consistently reported across studies, but problems. With severe tinnitus in adults, tinnitus prevalence is significantly higher coexisting factors may include hearing in pregnant than non-pregnant women.2 loss, dizziness, head injury, sinus and middle-ear infections, or mastoiditis The most common form of tinnitus is (infection of the spaces within the subjective tinnitus, which is noise that mastoid bone). -

Tinnitus in a Time of Chaos Calming the Mind

TINNITUSTODAY To Promote Relief, Help Prevent, and Find Cures for Tinnitus Vol. 45, No. 1, Spring 2020 Tinnitus in a Time of Chaos Calming the Mind Finding Mental Health Support Tinnitus Treatment Online Creating a Caring Community Apps for Managing Stress and Anxiety A publication of the Visit & Learn More About Tinnitus at ATA.org TinnitusToday Spring2020 09.indd 1 4/1/20 3:13 PM ATA thrives through the dedication of a vast number of people, all of whom make a difference. Join the Jack Vernon Legacy Society Jack Vernon co-founded ATA in 1971 to lead the way in researching a cure, developing effective treatments, and creating broad-based support and awareness of tinnitus. ATA invites individuals and organizations to join our journey. How can you contribute? Monthly or annual financial Gifts of stock contributions Gifts of real estate Name ATA in your trust or estate Deferred gift annuities Ask ATA to create a Tribute Page in Donations to ATA in lieu of flowers in memory of a loved one memory of a loved one Convert stock and/or real estate into a unitrust We hope you’ll be a part of the legacy of securing silence for those with tinnitus through a variety of treatments, as well as finding a cure for the millions who endure incessant noise and anxiety. For more information about adding ATA as a beneficiary or ways to reduce your taxes through charitable contributions, please contact Torryn Brazell, ATA’s Executive Director, via email at: [email protected] Table of Contents Vol. 45, No. -

Auditory Disabilities

DESCRIPTION OF AUDITORY DISABILITIES OVERVIEW For humans the primary, though not the only, use of the sense of hearing is in social communications.For this reason we focus primarily on the impact of hearing difficulties on language acquisition and development and social communications. Although a delay in language acquisition does not necessarily lead to grave consequences, age-appropriate verbal communications with adults and peers also promotes the development of general cognitive and social skills, so any language delays can impair other skills too, even those not directly linked to hearing. In addition, problems with language acquisition can be indicative of more serious developmental issues such specific language impairment, dyslexia or autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, early diagnosis of hearing impairment is important and has given rise in many countries to neonate hearing screening programmes. In considering auditory disabilities we distinguish between afferent problems that relate primarily to mechanistic audibility; i.e. whether and to what extent the acoustic signal is received and processed within the cochlea and correctly transmitted to the rest of the auditory system via the auditory nerve, and integrative problems that apply to the perception of complex sounds in general. In the next section problems relating specifically to language impairment will be discussed. The auditory system is rather different to the visual system in that a great deal more processing occurs before the signal reaches the cortex. In addition, there are no good animal models of auditory cortical processing due to the huge expansion of communication sounds in humans. Consequently rather less is understood about the cortical processing and representation of sounds than visual images. -

Dizziness: a Diagnostic Approach ROBERT E

Dizziness: A Diagnostic Approach ROBERT E. POST, MD, Virtua Family Medicine Residency, Voorhees, New Jersey LORI M. DICKERSON, PharmD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina Dizziness accounts for an estimated 5 percent of primary care clinic visits. The patient history can generally classify dizziness into one of four categories: vertigo, disequilibrium, presyncope, or lightheadedness. The main causes of ver- tigo are benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Meniere disease, vestibular neuritis, and labyrinthitis. Many medica- tions can cause presyncope, and regimens should be assessed in patients with this type of dizziness. Parkinson disease and diabetic neuropathy should be considered with the diagnosis of disequilibrium. Psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and hyperventilation syndrome, can cause vague lightheadedness. The differential diagnosis of dizziness can be nar- rowed with easy-to-perform physical examination tests, including evaluation for nystagmus, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, and ortho- static blood pressure testing. Laboratory testing and radiography play little role in diagnosis. A final diagnosis is not obtained in about 20 percent of cases. Treatment of vertigo includes the Epley maneu- ver (canalith repositioning) and vestibular rehabilitation for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, intratympanic dexamethasone or gentamicin for Meniere disease, and steroids for vestibular neuritis. Orthostatic hypotension that causes presyncope can be treated with alpha agonists, mineralocorticoids, -

Hyperacusis: Clinical Studies and Effect of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 934 Hyperacusis Clinical Studies and Effect of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy LinDA JÜRis ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 UPPSALA ISBN 978-91-554-8756-0 2013 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-207577 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Universitetshuset, room IX, Biskopsgatan 3, Uppsala, Thursday, October 31, 2013 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine). The examination will be conducted in Swedish. Abstract Jüris, L. 2013. Hyperacusis: Clinical Studies and Effect of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 934. 64 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-8756-0. Hyperacusis is a type of decreased sound tolerance where the individual has decreased loudness discomfort levels (LDL), normal hearing thresholds and is sensitive to ordinary environmental sounds. Persons with hyperacusis frequently seek help at audiological departments as they are often affected by other audiological problems. Regrettably, there is neither a consensus-based diagnostic procedure nor an evidence-based treatment for hyperacusis. The principal aim of this thesis was to gain knowledge about the clinical condition hyperacusis. The specific aim of Paper I was to compare hyperacusis measurement tools in order to determine the most valid measures for assessing hyperacusis. Items from a constructed clinical interview were compared with the LDL test, the Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). LDLs were significantly correlated with the anxiety subscale of the HADS. A third of the 62 investigated patients scored below the previously recommended cut-off for the HQ. -

A Study of Cochlear and Auditory Pathways in Patients with Tension-Type Headache Hang Shen1, Wenyang Hao2, Libo Li1, Daofeng Ni2, Liying Cui1 and Yingying Shang2*

Shen et al. The Journal of Headache and Pain (2015) 16:76 DOI 10.1186/s10194-015-0557-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access A study of cochlear and auditory pathways in patients with tension-type headache Hang Shen1, Wenyang Hao2, Libo Li1, Daofeng Ni2, Liying Cui1 and Yingying Shang2* Abstract Background: The purpose of this study was to systematically evaluate the function of cochlear and auditory pathways in patients suffering from tension-type headache (TTH) using various audiological methods. Methods: Twenty-three TTH patients (46 ears) and 26 healthy controls (52 ears) were included, and routine diagnostic audiometry, extended high-frequency audiometry, acoustic reflex (ASR), transient evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs), distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) and suppression TEOAEs were tested. Results: The TTH group showed higher thresholds (P < 0.05) for both pure tone and extended high-frequency audiometry at all frequencies except for 9, 14 and 16 kHz. All ASR thresholds were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the TTH group compared with the controls, except for the ipsilateral reflex at 1 kHz, but the threshold differences between the ASR and the corresponding pure tone audiometry did not differ (P>0.05). For the DPOAEs, the detected rates were lower (P < 0.05) in the TTH group compared with the controls at 4 and 6 kHz, and the amplitudes and signal to noise ratio (S/N) were not significantly different between groups. No differences in the TEOAEs (P >0.05) were observed for the detected rates, amplitudes, S/Ns or contralateral suppression, except for the S/Ns of the 0.5-1 kHz TEOAE responses, which were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the TTH group.