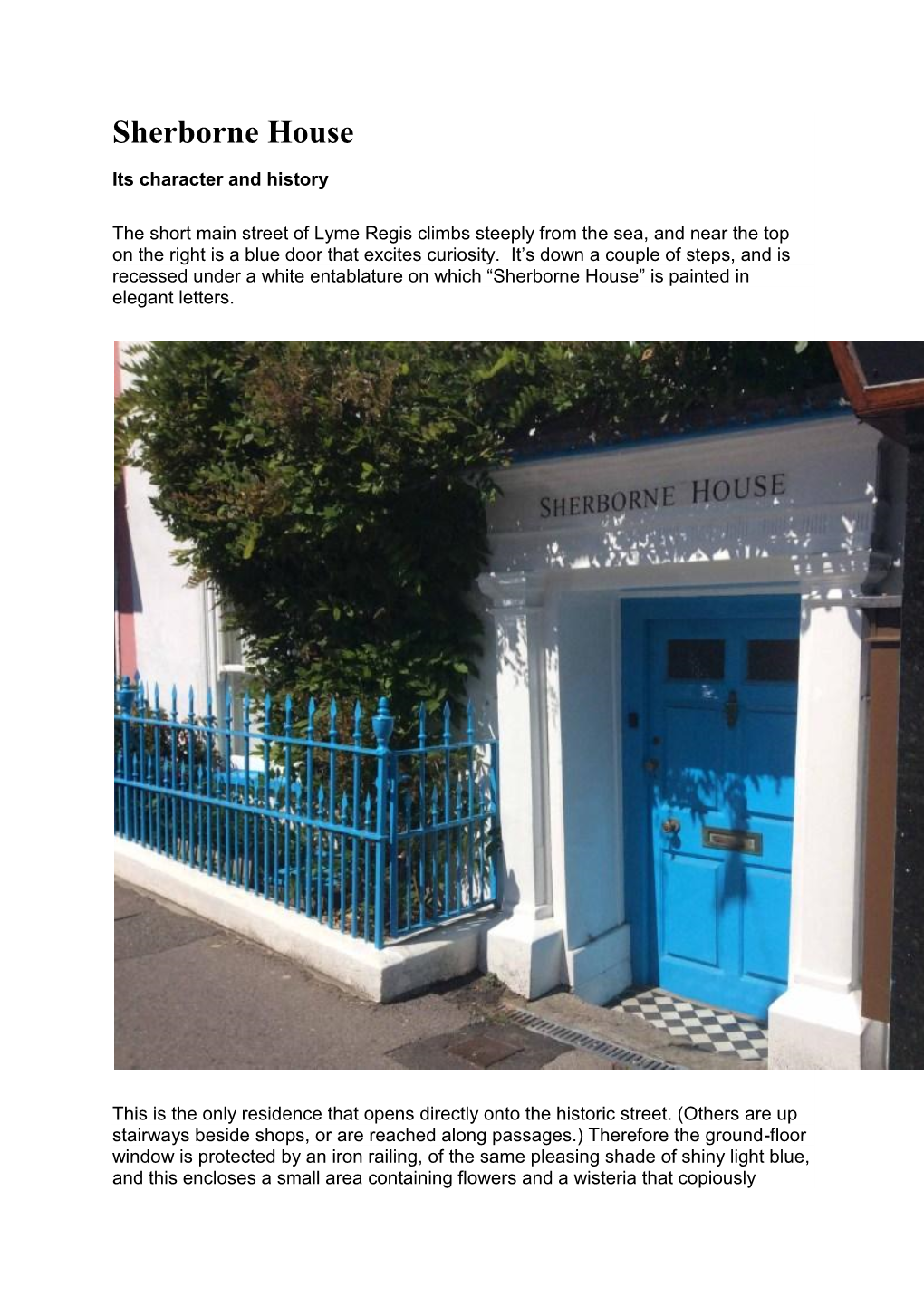

Sherborne House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

+44 (0)1844 277188 +44 (0) 20 7394 2100 +44 (0)20 7394 8061 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected]

ROPEWALK THREE PIGEONS BRUNSWICK HOUSE Arch 52, London Road, 30 Wandsworth Road, Maltby Street, Milton Common, Vauxhall, Bermondsey, Oxfordshire OX9 2JN London SW8 2LG London SE1 3PA www.lassco.co.uk +44 (0)1844 277188 +44 (0) 20 7394 2100 +44 (0)20 7394 8061 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SIR WILLIAM CHAMBERS' DOORCASE An important carved Portland Stone doorcase c.1769, by Chambers (1723-1796) for his own house in Berners Street Westminster the triangular pediment with dentil mouldings above the rusticated cushion moulded frieze centred by a keystone in Coade Stone modelled in relief with a female mask, the jambs constructed with alternating rusticated quoins, DIMENSIONS: 432cm (170") High, 244cm (96") Wide, 198 (78.5) wide at jambs, Aperture = 315 x 152cm (124 x 59.75 STOCK CODE: 43528 HISTORY Sir William Chambers (1723-96) is one of the most revered of Georgian neo-classical architects. In his early career he was appointed architectural tutor to the Prince of Wales, later George III. In 1766, he became Architect to the King, (this being an unofficial title, rather than an actual salaried post with the Office of Works). He worked for Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales building exotic garden buildings at Kew (the pagoda is his), and in 1757 he published a book of Chinese designs which had a significant influence on contemporary taste. He developed his Chinese interests further with his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772), a fanciful elaboration of contemporary English ideas about the naturalistic style of gardening in China. -

The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels

Marjan Sterckx The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008) Citation: Marjan Sterckx, “The Invisible ‘Sculpteuse’: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth- century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn08/90-the-invisible- sculpteuse-sculptures-by-women-in-the-nineteenth-century-urban-public-spacelondon-paris- brussels. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2008 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Sterckx: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Space–London, Paris, Brussels Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008) The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels[1] by Marjan Sterckx Introduction The Dictionary of Employment Open to Women, published by the London Women’s Institute in 1898, identified the kinds of commissions that women artists opting for a career as sculptor might expect. They included light fittings, forks and spoons, racing cups, presentation plates, medals and jewelry, as well as “monumental work” and the stone decoration of domestic facades, which was said to be “nice work, but poorly paid,” and “difficult to obtain without -

Issue 07 April 2016 Click Here

JARDINIQUE Garden Antiques ______________________________________________________________________________________________ What’s New at Jardinique this Spring? Come and See for Yourselves – A Warm Welcome Awaits! Our Coade Stone Collection Over the past 21 years we have come across many delightful pieces of garden antiques, but have been particularly pleased to find a number of Coade Stone pieces on our travels. As a result we now have two fine examples of a lion and figure of Venus on display for sale, the details of which are shown here and on our website. Coade Stone stems from the mid 18th century, and is a manufactured stone or stoneware resembling limestone. It comprises a mixture of ground glass, flint, sand, clay and petrified clay, a combination that often turned out to be more durable than the stone it was imitating. Poured into moulds, dried, fired at high temperatures in kilns and finished by hand, the process produced some wonderful, and at times quite complex, sculptures. Eleanor Coade’s artificial stone manufactory was established in 1769 at Lambeth - now the site of the Royal Festival Hall, manufacturing Coade Stone decorative sculpture and ornaments. Eleanor (1708-1796) and her daughter, also Eleanor (1733-1821), were both part of a handful of independent and enterprising 18th century women who established their own businesses. The Coade business flourished, and grew under its lead designer the neoclassical sculptor John Bacon who held the role until his death in 1799. In 1796 following the death of her mother, the younger Eleanor Coade went into partnership with John Sealy and subsequently her cousin William Croggan until her death in 1821. -

Alison Kelly, 'Eleanor Coade at Stowe', the Georgian Group Jounal

Alison Kelly, ‘Eleanor Coade at Stowe’, The Georgian Group Jounal, Vol. II, 1992, pp. 97–100 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 1992 ELEANOR CO ADE AT STOWE Alison Kelly towe is famous as the creation of many of the most eminent English architects, sculptors and garden designers, but one name rarely mentioned is that of Mrs SEleanor Coade.1 And yet Stowe had a range of Coade objects apparendy unrivalled at any other country house, stretching across nearly half a century from the 17 70s to at least 1814. Many of the Coade stone objects left Stowe at the sale of 1921, others have been overlooked thanks to Coade stone’s similarity to natural, fine-grained limestone, while the poor cataloguing of the 250,000 Stowe documents in the Huntington Library, San Marino, means that individual bills cannot be identified.2 Nevertheless, it is possible to give some impression of the range of Coade-stone objects at Stowe. In 1776 George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, later 1st Marquess of Buckingham, wrote to his uncle 2nd Earl Temple: “I have however seen a lion in artificial stone which I think will answer our purpose, and as the mold need not in this instance be destroyed I think we may have the pair for £100, perhaps this may be the cheapest way.”3 In fact the lions only came to £40 but the bill, dated 1778, does not specify the type of lion sent.4 The lions on the north portico, now in front of the school sports pavilion, were definitely Coade stone (Fig. I). -

Winchester Stone by Dr John Parker (PDF)

Winchester Stone by John Parker ©2016 Dr John Parker studied geology at Birmingham and Cambridge universities. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of London. For over 30 years he worked as an exploration geologist for Shell around the world. He has lived in Winchester since 1987. On retirement he trained to be a Cathedral guide. The Building of Winchester Cathedral – model in the Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux 1 Contents Introduction page 3 Geological background 5 Summary of the stratigraphic succession 8 Building in Winchester Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon periods 11 Early medieval period (1066-1350) 12 Later medieval period (1350-1525) 18 16th to 18th century 23 19th to 21st century 24 Principal stone types 28 Chalk, clunch and flint 29 Oolite 30 Quarr 31 Caen 33 Purbeck 34 Beer 35 Upper Greensand 36 Portland 38 Other stones 40 Weldon 40 Chilmark 41 Doulting 41 French limestones 42 Coade Stone 42 Decorative stones, paving and monuments 43 Tournai Marble 43 Ledger stones and paving 44 Alabaster 45 Jerusalem stone 45 Choice of stone 46 Quarries 47 A personal postscript 48 Bibliography and References 50 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Photographs and diagrams are by the author, unless otherwise indicated 2 Introduction Winchester lies in an area virtually devoid of building stone. The city is on the southern edge of the South Downs, a pronounced upland area extending from Salisbury Plain in the west to Beachy Head in the east (Figs. 1 & 2). The bedrock of the Downs is the Upper Cretaceous Chalk (Fig. 3), a soft friable limestone unsuited for major building work, despite forming impressive cliffs along the Sussex coast to the east of Brighton. -

Revisiting the Origins of Coade Stone’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Caroline Stanford, ‘Revisiting the origins of Coade Stone’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 95–116 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 REVISITING THE ORIGINS OF CoaDE StoNE CAROLINE STANFORD Eleanor Coade’s fired artificial stone was widely (1990), remains the most authoritative treatment used in the embellishment of architecture, and also of the subject, a near comprehensive gazetteer of achieved unique reputation in the reproduction, and surviving and lost examples. Buried within it are indeed creation, of sculpture in the late Georgian references to most extant Coade examples and period. Coade stone’s fame persists, but so too do documentary sources. However, Kelly’s material certain myths about its composition and origins. This does not lightly yield its nuggets to the reader and paper provides a distillation of current knowledge on provides little on Coade’s contemporary context. Coade’s predecessors in the manufacture of artificial Even if dispelled by Kelly, misapprehensions about stone from 1720; on the Coade stone formula, and on Coade stone continue to circulate widely – that the Coade manufactory in Lambeth. It also sets Mrs it was a single secret recipe that died with Coade Coade within her contemporary context and identifies herself; that she invented it; that it was a cast, rather the key reasons for her enduring success than ceramic stone. Kelly initiated scientific analysis of Coade stone’s composition as early as 1985, but he existence and ubiquitous use of Eleanor1 the publication of these results was obscure to the TCoade’s eponymous artificial stone is general researcher. widely known. Coade stone is a fired ceramic, a The published eighteenth-century sources about combination of raw ball clay and finely ground artificial stone and the practitioners that preceded pre-fired terracotta, silicates and glass. -

Cracking the Mysteries of Coade

However broadly true this is, there is still the f you have a piece of Coade occasional find in a humbler listed dwelling, stone inside or outside of particularly if the house dates from the your house – treasure it. In Georgian period. I always speculate that there Cracking the 50 years of enthusiastic study must be a large number of as yet undiscovered of traditional English house styles, Coade stone pieces in garden settings. I have yet to meet a person with I I continue to be amazed not only by many any Coade stone item in his or her house. Perhaps this is because aspects of this extraordinary material, but mysteries of Coade of my lack of connections; you also that relatively few listed property will generally only find a piece of owners seem to be aware of how fascinating it is. Coade stone is a remarkably hard and Coade stone in grander houses weatherproof artificial stone made from 1769 and public buildings. until 1836 in the factory of Mrs Eleanor Coade by Clive Fewins (1733-1821) and her successors at Lambeth. Using designs by neo-classical architects and sculptors, the factory turned out cast pieces of exceptional durability. They were designed for doorways and porches, gate piers, pediments, keystones, reliefs to set in walls, chimneypieces, church memorials, churchyard table tombs and even fonts. The factory also produced countless statues of nymphs and river gods, garden urns and vases. Continued >> The Gosford Swan: Philip Thomason made three in Coade Stone (see later pages) to replace missing ones at a mansion near Edinburgh -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

Coade, Blashfield Or Doulton? the In-Situ Identification of Ceramic Garden Statuary and Ornament from Three Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Manufacturers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository Coade, Blashfield or Doulton? The in-situ identification of ceramic garden statuary and ornament from three eighteenth and nineteenth century manufacturers. Laura E. Karran Visiting Researcher School of Chemistry University of Lincoln Brayford Pool Lincoln LN6 7TS, UK T: +44 1223 313380 E: [email protected] Belinda J Colston* Professor of Analytical Chemistry and Cultural Heritage School of Chemistry, University of Lincoln, Brayford Pool, Lincoln LN6 7TS, UK T: +44 1522 837448 E: [email protected] Corresponding author Abstract In the eighteenth century, the emergence of a neo-classical style in architecture created a growing demand for a range of classically-inspired products - not only for architectural decoration but also for ornamentation of the garden. Producing individual items in stone, however, was time-consuming and expensive, so cheaper clay-based alternatives were adopted, most notably from manufacturers such as Coade (1769-1830), Blashfield (1840s-1875) and Doulton (1854-1890s). The artefacts of these manufacturers are now considered of high historic value and significance and their identification is important, not only for the historical record, but also for provision of the evidence necessary to carry out informed conservation. As the sale and copy of moulds was common practice during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, stylistic considerations do not provide reliable identification. Through the analysis of 24 historic objects of garden statuary and ornamentation, this research evaluates the use of portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (pXRF), and more specifically element profiles, in identifying, and differentiating between the products of Coade, Blashfield and Doulton. -

Page 1 of 32 Marjan Sterckx on Sculptures by Women in The

Marjan Sterckx on Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Spa... Page 1 of 32 | Print | The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels1 by Marjan Sterckx Introduction The Dictionary of Employment Open to Women, published by the London Women’s Institute in 1898, identified the kinds of commissions that women artists opting for a career as sculptor might expect. They included light fittings, forks and spoons, racing cups, presentation plates, medals and jewelry, as well as “monumental work” and the stone decoration of domestic facades, which was said to be “nice work, but poorly paid,” and “difficult to obtain without personal acquaintance with architects.”2 The Dictionary confirms that, despite the nineteenth-century ideology of “separate spheres,” according to which public and private spaces were the domains of men and women, respectively, female artists were not entirely confined in their production to small-scale and small-time art for the home, such as spoons, embroidery, quilts, ceramics, watercolor or porcelain painting, but were sometimes asked to create more public art forms, such as large history paintings and monumental sculptures. Notwithstanding the many obstacles they faced because of their sex, many women did practice the “male” profession of sculpture, and several of them were working on public sculptures, even in the major nineteenth-century metropolises. In line with recent historical research focusing on the experiences of middle-class women in the urban public space3—research that often qualifies or even refutes strict gender partition—a case study of sculptures by women artists suggests as well that the public-private divide was not so clear-cut. -

Revisiting the Origins of Coade Stone

REVISITING THE ORIGINS OF CoaDE StoNE CAROLINE STANFORD Eleanor Coade’s fired artificial stone was widely (1990), remains the most authoritative treatment used in the embellishment of architecture, and also of the subject, a near comprehensive gazetteer of achieved unique reputation in the reproduction, and surviving and lost examples. Buried within it are indeed creation, of sculpture in the late Georgian references to most extant Coade examples and period. Coade stone’s fame persists, but so too do documentary sources. However, Kelly’s material certain myths about its composition and origins. This does not lightly yield its nuggets to the reader and paper provides a distillation of current knowledge on provides little on Coade’s contemporary context. Coade’s predecessors in the manufacture of artificial Even if dispelled by Kelly, misapprehensions about stone from 1720; on the Coade stone formula, and on Coade stone continue to circulate widely – that the Coade manufactory in Lambeth. It also sets Mrs it was a single secret recipe that died with Coade Coade within her contemporary context and identifies herself; that she invented it; that it was a cast, rather the key reasons for her enduring success than ceramic stone. Kelly initiated scientific analysis of Coade stone’s composition as early as 1985, but The existence and ubiquitous use of Eleanor1 the publication of these results was obscure to the Coade’s eponymous artificial stone is widely known. general researcher. Coade stone is a fired ceramic, a combination of The published eighteenth-century sources about raw ball clay and finely ground pre-fired terracotta, artificial stone and the practitioners that preceded silicates and glass. -

The William Shipley Group for Rsa History

THE WILLIAM SHIPLEY GROUP FOR RSA HISTORY Newsletter 47 December 2015 FORTHCOMING EVENTS Tuesday 2 February 2016 at 6.30pm. Sir John Hawkshaw and the Severn Tunnel. The Victorian Society Lecture will take place at the Art Workers’ Guild, 6 Queen Square, London WC1. Tickets £11 on door. Sir John Hawkshaw (1811-1891), an active member of the civil engineering projects, to provide a direct link from England toSociety South of Wales Arts, with designed the construction one of the mostof the difficult Severn Tunnel,19th century which remained the longest tunnel in Britain until 2007. For booking Sir John Hawkshaw inspecting the Severn information see http://www.victoriansociety.org.uk/events/lec- Tunnel during construction ture-sir-john-hawkshaw-and-the-severn-tunnel/ Wednesday 16 March 2016 at 2.45pm. The William Shipley Group 12th Annual General Meeting and Annual Address (details to follow) Wednesday 17 March 2016 from 10.00am. Animating the Georgian London Town House. A conference organised by the Paul Mellon Centre, the National Gallery and Birkbeck College will be held in the Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre, National Gallery, London, WC2N 5DN. Tickets: £55 /£48 senior citizens/£45 National Gallery Members/£28 students Expert speakers will discuss both famed and little-remembered London houses, and discuss how these residences were designed, these properties for owners and their families and the experience offurnished guests andand visitors ornamented. will also The be considered.significance Seeand http://www. function of - gian-london-town-house-conf-prog.pdf for full programme. paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/media/_file/events/animating-geor Spencer House Saturday 7 May 2016.