H Geography / / 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

7112712551213Eokjhjustificati

Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre- Final Alignment construction services in respect of 2 laning of Pallel-Chandel Option Study Report Section of NH- 102C on Engineering, Procurement and Construction mode in the state of Manipur. ALIGNMENT OPTION STUDY 1.1 Prologue National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) is a fully owned company of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H), Government of India. The company promotes, surveys, establishes, design, build, operate, maintain and upgrade National Highways and Strategic Roads including interconnecting roads in parts of the country which share international boundaries with neighboring countrie. The regional connectivity so enhanced would promote cross border trade and commerce and help safeguard India’s international borders. This would lead to the formation of a more integrated and economically consolidated South and South East Asia. In addition, there would be overall economic benefits for the local population and help integrate the peripheral areas with the mainstream in a more robust manner. As a part of the above mentioned endeavor, National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has been entrusted with the assignment of Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning with paved of Pallel-Chandel Section of NH-102C in the state of Manipur. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. is the employer and executing agency for the consultancy services and the standards of output required from the appointed consultants are of international level both in terms of quality and adherence to the agreed time schedule. -

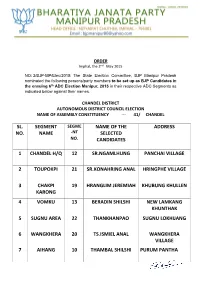

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

Combating Illegal Trade of Scaly Giants Through Community Participation In

Combating illegal trade of scaly giants through community participation in Manipur, India Final report submitted To Rufford Small Grant Foundation By Principal Investigator Dr Janmejay Sethy Co-Investigator Dr. C. Murali Krishna Combating illegal trade of scaly giants through community participation in Manipur, India Final report submitted to Rufford Small Grant Foundation By Principal Investigator Dr Janmejay Sethy Co-Investigator Dr. C. Murali Krishna Researcher (s) Mr. Prazual Gurung Mr. Khamchuckm Ronald Combating illegal trade of scaly giants through community participation in Manipur. Sethy et al 2018 Contents Page No. Acknowledgements-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------ii Summary----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------iii 1. Introduction--------------------------------------------------------------------------------1-7 2. Study Area--------------------------------------------------------------------------------8-10 3. Objectives------------------------------------------------------------------------------------10 4. Methodology-----------------------------------------------------------------------------10-11 5. Results------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13-49 6. Discussion--------------------------------------------------------------------------------50-51 7. Conclusion-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------52 8. References-------------------------------------------------------------------------------52-57 -

MANIPUR a Joint Initiative of Government of India and Government of Manipur

24 X 7 POWER FOR ALL - MANIPUR A Joint Initiative of Government of India and Government of Manipur Piyush Goyal Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Government of India Power, Coal, New & Renewable Energy Foreword Electricity consumption is one of the most important indicator that decides the development level of a nation. The Government of India is committed to improving the quality of life of its citizens through higher electricity consumption. Our aim is to provide each household access to electricity, round the clock. The ‘Power for All’ programme is a major step in this direction. This joint initiative of Government of India and Government of Manipur aims to further enhance the satisfaction levels of the consumers and improve the quality of life of people through 24x7- power supply. This would lead to rapid economic development of the state in primary, secondary & tertiary sectors resulting in inclusive development. I compliment the Government of Manipur and wish them all the best for implementation of this programme. The Government of India will complement the efforts of Government of Manipur in bringing uninterrupted quality power to each household, industry, commercial business, small & medium enterprise and establishment, any other public needs and adequate power to agriculture consumer as per the state policy. Government of Okram Ibobi Singh Manipur Chief Minister of Manipur Foreword Electricity is critical to livelihoods and essential to well-being. Dependable electricity is the lifeline of industrial and commercial businesses, as well as a necessity for the productivity and comfort of residential customers. The implementation of 24x7 “Power For All” programme is therefore a welcome initiative. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District 2014

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 2014 DISTRICT STATISTICAL OFFICE, UKHRUL DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR PREFACE The present issue of ‘Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District, 2014’ is the 8th series of the publication earlier entitled „Statistical Abstract of Ukhrul District, 2007‟. It presents the latest available numerical information pertaining to various socio-economic aspects of Ukhrul District. Most of the data presented in this issue are collected from various Government Department/ Offices/Local bodies. The generous co-operation extended by different Departments/Offices/ Statutory bodies in furnishing the required data is gratefully acknowledged. The sincere efforts put in by Shri N. Hongva Shimray, District Statistical Officer and staffs who are directly and indirectly responsible in bringing out the publications are also acknowledged. Suggestions for improvement in the quality and coverage in its future issues of the publication are most welcome. Dated, Imphal Peijonna Kamei The 4th June, 2015 Director of Economics & Statistics Manipur. C O N T E N T S Table Page Item No. No. 1. GENERAL PARTICULARS OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 1 2. AREA AND POPULATION 2.1 Area and Density of Population of Manipur by Districts, 2011 Census. 1 2.2 Population of Manipur by Sector, Sex and Districts according to 2011 2 Census 2.3 District wise Sex Ratio of Manipur according to Population Censuses 2 2.4 Sub-Division-wise Population and Decadal Growth rate of Ukhrul 3 District 2.5 Population of Ukhrul District by Sex 3 2.6 Sub-Division-wise Population in the age group 0-6 of Ukhrul District by sex according to 2011 census 4 2.7 Number of Literates and Literacy Rate by Sex in Ukhrul District 4 2.8 Workers and Non-workers of Ukhrul District by sex, 2001 and 2011 5 censuses 3. -

Stratified Random Sampling - Manipur (Code -21)

Download The Result Stratified Random Sampling - Manipur (Code -21) Species Selected for Stratification = Cattle + Buffalo Number of Villages Having 100 + (Cattle + Buffalo) = 728 Design Level Prevalence = 0.2 Cluster Level Prevalence = 0.03 Sensitivity of the test used = 0.9 Total No of Villages (Clusters) Selected = 110 Total No of Animals to be Sampled = 1430 Back to Calculation Number Cattle of units Buffalo Cattle DISTRICT_NAME BLOCK_CODE BLOCK_NAME VILLAGE_NAME Buffaloes Cattle + all to Proportion Proportion Buffalo sample Nambol (M Cl) Bishnupur 29 Nambol 0 288 288 288 13 0 13 (Part) - Ward No.5 Ningthoukhong Bishnupur 31 Ningthoukhong 0 310 310 310 13 0 13 (NP) - Ward No.14 Nambol (M Cl) Bishnupur 29 Nambol 0 452 452 458 13 0 13 (Part) - Ward No.16 Bishnupur 27 Moirang Thamnapokpi 0 737 737 737 13 0 13 Chandel 24 Machi T.Hlangnom 19 95 114 148 13 2 11 Chrang Ching Chandel 4 Chandel 53 63 116 116 13 6 7 Khullen Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Minou 5 113 118 118 13 1 12 Chandel 4 Chandel Khudei Khunou 14 114 128 145 13 1 12 Chandel 24 Machi Phunchong 2 151 153 175 13 0 13 Chandel 24 Machi Salemram 0 159 159 177 13 0 13 Chandel 24 Machi Maringphai 2 165 167 187 13 0 13 Chandel 24 Machi Lamlong Khullen 0 168 168 168 13 0 13 Chandel 4 Chandel Kakching Mantak 27 174 201 271 13 2 11 Chandel 3 Chakpikarong Sajik Tampak 124 84 208 246 13 8 5 Chandel 24 Machi Heinoukhong 0 249 249 249 13 0 13 Chandel 4 Chandel Phunansambum 22 272 294 369 13 1 12 Laiching Chandel 24 Machi 0 308 308 414 13 0 13 Kangshang Chandel 24 Machi Kangoi Khullen 52 287 339 454 13 2 11 Chandel 24 Machi Thamlai 0 355 355 355 13 0 13 Churachandpur 5 Churachandpur L.Semol 0 102 102 102 13 0 13 Churachandpur 5 Churachandpur Lanva 0 123 123 123 13 0 13 Churachandpur 5 Churachandpur T. -

MSME) MANIPUR ( EM Part-II Filed As on 2013-2014

DIRECTORY OF MICRO, SMALL & MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (MSME) MANIPUR ( EM Part-II filed as on 2013-2014 ) VOLUME-I Department of Commerce & Industries Government of Manipur Govvindas Konthoujam Minister Commerce & Industries Veterinary & An imal Husban dry and Sericulture Manipur MESSAGE I am happy to learn that the Directorate of Commerce & Industries, Manipur, is publishing a Directory of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The importance of a Directory is needless to mention as all the vital information of an enterprise can be known from this Directory easily. The tireless efforts and endeavours rendered by S/Shri M. Lyanchinpao (Statistical Supervisor), N. Rupachandra Singh (Statistical Supervisor), Ch. Khogendra Singh (Statistical Supervisor) and M. Kunjeshwar Meetei (Extension Officer) and RV. John, OSD (Nucleus Cell) under the guidance of Shri B. John Tlangtinkhuma, IAS, Director of Commerce & Industries, Manipur for printing of the Directory is highly appreciated. It may not be out of place to mention that the valuable contribution made by Shri S. Birendra Singh, former Functional Manager (KVI), OSD Handicrafts/Nucleus Cell who took the initial role to publish this Directory, deserves special appreciation from all the hearts involved in the production of such an important Directory. I hope that this Directory will be useful for the Entrepreneurs, Econoomists and Scholars for various purposes as growth of MSMEs, its employment, production, etc. are included in this Directory with graphical presentation and tabulation. I wish the publication all success. (Govindas Konthoujam) Lungmuana Lakher IAS Prrincipal Secretary(C&I) FOREWORD It gives me immense pleasure to learn that the Directorate of Commerce & Industries, Manipur, is bringing out a Directory of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) for the years 2007-08 to 2013-14. -

Economic Survey Manipur 2018-19

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR Economic Survey Manipur 2018-19 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR LAMPHELPAT Website: desmanipur.gov.in Email: [email protected] P R E F A C E The ‘Economic Survey, Manipur, 2018-19’ presents a broad analysis of the latest economic situation of the state based on performance appraisal data collected from various sources. It is the 23rdissue of the series. The general observation and status of the various sectors of the State’s economy is briefly discussed in Part-I and supporting statistical tables are presented in Part-II. Some of the chapters/tables have been modified in the present issue on the basis of the data-base made available by the different Agencies/Departments. The district level data presented herein relates to the 9 (Nine) Districts which existed before the creation of the new 7 (Seven) Districts in December, 2016 except those for which the concerned department is able to furnish information for the 16 districts. Certain information are depicted in the form of charts. A special report on the achievement of some State Government Department of Manipur under the ‘GO TO VILLAGE MISSION’ is presented in the current publication. It is hoped that with the active co-operation of different Organisations/Departments, the Directorate will be able to make improvements in the quality and contents of the publication in its future issues. The co-operation and help extended spontaneously by different Departments of the Government, local bodies and private institutions are gratefully acknowledged. I also appreciate all the officers and staff of the Economic Analysis (EA) and Coordination and Publications (COP) Units of the Directorate for their untiring efforts put in for preparation of the current issue of the publication. -

Executive Summary

Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Project Report DETAILED PROJECT REPORT for 2 Laning of Hungpung-Longpi Kajui Road on NH 202 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 0.1 GENERAL National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has decided to take up the development of various National Highways Corridors in the North-eastern state where the intensity of traffic has increased significantly in plain areas and where there is requirement of safe and efficient movement of traffic mainly in hilly terrains. This project is a part of the above mentioned programme and the project awarded to Consultant is Consultancy Services for carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning of Yaingangpokpi-Nagaland Border in the state of Manipur. Project Stretch: Hungpung-Longpi Kajui (36.423Km). The NHIDCL has been entrusted with implementation of the development of this corridor from Ministry’s Plan Funds. In order to fulfil the above task, NHIDCL has entrusted the work of preparation of the feasibility study and Detailed Project Report for the above project to M/s S. M. Consultants., vide contract agreement dated 19th January 2017. The Letter of Acceptance was communicated vide letter No NHIDCL/DPR/IM&UJ/Manipur/2016/293. 0.2 OBJECTIVE The main objectives of the consultancy service will focus on establishing technical, financial viability of the project and prepare detailed project reports for rehabilitation/ upgradation/ construction of the existing road to two lane NH with paved shoulder configuration with the following points to be ensured. Ensure Enhanced safety of the traffic, the road users and people living close to the Highway . -

Social and General Sectors Government of Manipur

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Social and General Sectors For the year ended 31 March 2017 GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR Report No. 2 of 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph Page Preface - v Executive Summary - vii CHAPTER I SOCIAL SECTOR Introduction 1.1 1 PERFORMANCE AUDIT RELIEF AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT Performance Audit of Relief and Disaster Management 1.2 3 Department COMPLIANCE AUDIT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION (SCHOOLS) Diversion of funds 1.3 40 MEDICAL HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT Medical equipment not installed 1.4 41 MINORITIES, OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES AND SCHEDULE CASTE DEPARTMENT Blockage of fund 1.5 43 RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYATI RAJ DEPARTMENT Irregular transfer of fund to Bank Account 1.6 45 FOLLOW-UP AUDIT YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS DEPARTMENT Follow-up Audit of “Youth Affairs and Sports Department” 1.7 47 i Audit Report on Social and General Sectors for the year ended 31 March 2017 CHAPTER II GENERAL SECTOR Introduction 2.1 57 PERFORMANCE AUDIT PLANNING DEPARTMENT Performance Audit on Implementation of Border Area 2.2 59 Development Programme COMPLIANCE AUDIT PLANNING DEPARTMENT Undue benefit to contractors 2.3 79 CHAPTER III FOLLOW UP OF AUDIT OBSERVATIONS Follow up on Audit Reports 3.1 81 Action taken on the recommendations of Public Accounts 3.2 81 Committee Monitoring of Audit observations 3.3 82 Response to Audit observations and outstanding Inspection 3.4 82 Reports APPENDICES Details of funds transferred directly to Implementing Agencies 1.1 85 under Social Sector Year-wise details