Signature Redacted Signature of Author Center for R4ste January 12Phy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harlem Transportation Study

3.0 LAND USE AND ZONING Zoning The city is divided into three basic zoning districts: residential (R), commercial (C), and manufacturing (M). The three basic categories are further subdivided into lower, medium, and higher density residential, commercial and manufacturing districts. Development within these districts is regulated by use, building size, and parking regulations. Here is a brief description of the three basic zoning districts according to the Zoning Handbook: Residential District (R) In New York City, there are ten standard residential districts, R1 through R10. The numbers refer to the permitted density (R1 having the lowest density and R10 the highest) and other controls such as required parking. A second letter or number signifies additional controls are required in certain districts. R1 and R2 districts allow only detached single-family residences and certain community facilities. The R3-2 through R10 districts accept all types of dwelling units and community facilities and are distinguished by differing bulk and density, height and setback, parking, and lot coverage or open space requirements. Commercial District (C) The commercial districts reflect the full range of commercial activity in the city from local retail and service establishmentsDRAFT to high density, shopping, entertainment and office uses. There are eight basic commercial districts where two (C1 and C2 districts) are designed to serve local needs, one district (C4) is for shopping centers outside the central business district, two (C5 and C6 districts) are for the central business districts which embrace the office, retail, and commercial functions that serve the city and region, and three (C3, C7, and C8 districts) are designed for special purposes (waterfront activity, large commercial amusement parks and heavy repair services). -

The Retail Pulse Updates & Trends

May 2013 The Retail Pulse Updates & Trends Real estate investment services May 2013 New York City’s Strong Investor Demand Defi es Property Sales Volatility Tourists from around the world are not the only ones interested in New York City’s retail offerings, real estate investors have been scouring the City to BUY retail properties boosting sales volume at the end of 2012. Yet despite the numerous anecdotal stories confi rming how New York’s economy is thriving, the retail property sales sta- tistics were disappointing in the fi rst quarter of 2013. Volume fell signifi cantly, but this was expected given the rush at the end of 2012 to close deals before the capital gains tax increased as it did at the 11th hour. As per Chairman and CEO, Peter Hauspurg, “To no one’s surprise, sales volume fell in the fi rst quarter but investor inter- est has been strong. Because prices are climbing every day, more sellers are bringing properties to the market. While we will not see the same fourth quarter 2012 volume in the next quarter or two, the statistics will start to refl ect the high demand we are seeing in the market.” This issue of Eastern Consolidated’s Retail Pulse report will review every statistic pertaining to the retail industry in New York City. The fi ndings are compelling and show why New York City has retained its title of “Retail Capital of the World:” — Retail property sales volume declined in early 2013, but this was expected given the surge at the end of 2012. -

Stephen Ison and Jon Shaw

PARKING ISSUES AND POLICIES TRANSPORT AND SUSTAINABILITY Series Editors: Stephen Ison and Jon Shaw Recent Volumes: Volume 1: Cycling and Sustainability Volume 2: Transport and Climate Change Volume 3: Sustainable Transport for Chinese Cities Volume 4: Sustainable Aviation Futures TRANSPORT AND SUSTAINABILITY VOLUME 5 PARKING ISSUES AND POLICIES EDITED BY STEPHEN ISON Transport Studies Group, Loughborough University, UK CORINNE MULLEY Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, The University of Sydney Business School, Sydney, Australia United Kingdom À North America À Japan India À Malaysia À China Emerald Group Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2014 Copyright r 2014 Emerald Group Publishing Limited Reprints and permission service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters’ suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-78350-919-5 ISSN: 2044-9941 (Series) ISOQAR certified Management System, awarded to Emerald for adherence to Environmental standard ISO 14001:2004. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

East Harlem, Manhattan (September 2016)

PLACE-BASED COMMUNITY BROWNFIELD PLANNING FOUNDATION REPORT ON EXISTING CONDITIONS EAST HARLEM, MANHATTAN FINAL SEPTEMBER 2016 BILL deBLASIO MAYOR DANIEL C. WALSH, Ph.D. DIRECTOR Mayor’s Office of Environmental Remediation This document was prepared by the New York City Department of City Planning for the New York City Mayor’s Office of Environmental Remediation and the New York State Department of State with state funds provided through the Brownfield Opportunity Areas Program. CONTENTS PURPOSE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 PART ONE Geography and Land Use 10 Demographic and Economic Profile 28 Recent Public Initiatives and Private Investments 35 PART TWO Environmental Conditions 41 Potential Strategic Sites 43 KEY FINDINGS AND NEXT STEPS 57 APPENDIX 58 PURPOSE This existing conditions foundation report was commissioned by the New York City Mayor’s Office of Environmental Remediation (OER) to help community members and community-based organizations (CBO’s) conduct place-based planning for revitalization of vacant and underutilized brownfield properties. Place- based planning by community groups is supported by OER under the NYC Place-Based Community Brownfield Planning Program and by the New York State Department of State in the Brownfield Opportunity Area Program. To advance implementation of plans, OER provides financial and technical assistance to CBO’s for cleanup and redevelopment of brownfield properties and seeks to help people foster greater health and well-being in their neighborhoods. Brownfields are vacant or underutilized properties where environmental pollution has deterred investment and redevelopment. Pollution introduces many risks to land development and often causes community and private developers to pass over these properties, especially in low-income neighborhoods where land values may be depressed and insufficient to cover added cleanup costs. -

Chapter 16: Traffic and Parking A. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 16: Traffic and Parking A. INTRODUCTION The Bronx Terminal Market parcel is located along River Avenue and Exterior Street, in close proximity to Yankee Stadium and alongside (as well as beneath) the Major Deegan Expressway. The site borders the Harlem River north of the 145th Street Bridge and is within the Bronx’s grid street network of north-south avenues and east-west cross-streets. Although the Major Deegan Expressway is frequently congested in the northbound direction during peak traffic hours due to delays further north at the Cross Bronx Expressway exit, many sections of the local street network that serve the site have substantial amounts of unused capacity, particularly Exterior Street, which bisects the site. Some sections of the local street network—most notably the approach and departure routes to/from the 145th Street and Macombs Dam Bridges, the Major Deegan Expressway, and River Avenue before and after Yankee games—carry substantial traffic volumes, which at times are congested. This chapter addresses the potential traffic and parking impacts of the Proposed Project. The approach routes to the site traverse intersections along 138th, 149th, and 161st Streets, Exterior Street, River Avenue, the Grand Concourse, the 145th Street and Macombs Dam Bridges, and the Major Deegan Expressway exits immediately north and south of the Bronx Terminal Market. Therefore, the traffic and parking analyses cover a large study area encompassing 15 existing intersections plus new intersections created for access to and from the project’s parking garages. Key segments of the Major Deegan Expressway have also been studied (see Figures 16-1 and 16-2). -

Winnovative HTML to PDF Converter for .NET

Reproduced with permission from Real Estate Law & Industry Report, 4 REAL 275 (Apr. 19, 2011). Copyright ©2011 by The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033), http://www.bna.com Multi-Family Housing East Harlem Multi-Family Rises in Value; Experts See ‘Tremendous Strength’ in Area Although the median sales price for apartments and condominiums in East Harlem, N.Y., is just less than half the median price in New York City itself, recently constructed or renovated apartment buildings are bringing in rents above $9,000 per month. Real estate professionals say they are confident land and property values in the area will continue to rise. Flanked to the east and north by the Harlem River and Fifth Avenue to the west, East Harlem’s southern border is 96th Street, where the Upper East Side ends. Once known as Spanish Harlem, synonymous with street crime and Latin music, East Harlem has been improving its image and its housing stock for more than a decade. Gentrification started around 96th Street, but new rental and condo development quickly crept up to the higher streets, and the population has become genuinely mixed, according to published reports. The median sales price for homes in East Harlem from Jan. 11 to March 11 was $546,140, a decline of 3.8 percent over the last quarter, but an increase of 23.3 percent year-over-year. The median sales price in East Harlem is 47.33 percent lower than the median sales price for the rest of New York City. The average price per square foot for residences in East Harlem was $603 in the most recent quarter, which is 54.07 percent lower than the average price per square foot for residences in other parts of Manhattan, according to published real estate data. -

Appendix Q: References

Appendix Q: References 125th Street Business Improvement District. Website. www.125thstreetbid.com. Accessed April 3, 2002. Able, K.W., J.P. Manderson, and A.L. Studholme. “Habitat Quality for Shallow Water Fishes in an Urban Estuary: The Effects of Man-Made Structures on Growth.” Marine Ecology Progress Series 187(1999): 227-235. Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Guidelines. November 25, 1980. Allee King Rosen & Fleming, Inc. (now AKRF, Inc.) Historic Resource Inventory Forms. 2002. ———. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Rezoning Final Environmental Impact Statement. 2001. ———. New Research Building at the Rockefeller University Environmental Assessment Statement. 2001. ———. New York University School of Medicine East River Science Park Final Environmental Impact Statement. 2001. Allee King Rosen & Fleming, Inc. (now AKRF, Inc.) et al. Proposed Sale of Con Edison Properties to FSM—Draft Generic Environmental Impact Statement. 2002. ———. East Side Access Final Environmental Impact Statement. 2001. ———. Final Environmental Impact Statement for New York City’s Adult Mosquito Control Programs. 2001. ———. Metropolitan Transportation Authority/New York City Transit Manhattan East Side Transit Alternatives Major Investment Study Draft Environmental Impact Statement. 1999. ———. Hudson River Park Final Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix B, Natural Resources. 1998. ———. Cooper Square Preliminary Draft Environmental Impact Statement. 1991. Alliance for Downtown New York website. www.downtownny.com. Accessed on April 3, 2002. Anderson, H.R. “Air Pollution and Trends in Asthma.” The Rising Trends in Asthma. Ciba Foundation Symposium 206: 90-207. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY. 1997. Bauer, Matthew. Director of the Madison Avenue Business Improvement District. Telephone interview. April 10, 2002. Benarie, M.M. Urban Air Pollution Modeling. -

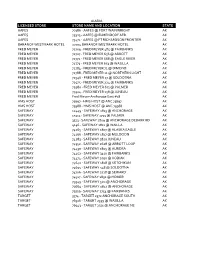

Licensed Store Store Name and Location State

ALASKA LICENSED STORE STORE NAME AND LOCATION STATE AAFES 70386 - AAFES @ FORT WAINWRIGHT AK AAFES 75323 - AAFES @ ELMENDORF AFB AK AAFES 75471 - AAFES @ FT RICHARDSON FRONTIER AK BARANOF WESTMARK HOTEL 22704 BARANOF WESTMARK HOTEL AK FRED MEYER 72709 - FRED MEYER 485 @ FAIRBANKS AK FRED MEYER 72727 - FRED MEYER 656 @ ABBOTT AK FRED MEYER 72772 - FRED MEYER 668 @ EAGLE RIVER AK FRED MEYER 72773 - FRED MEYER 653 @ WASILLA AK FRED MEYER 72784 - FRED MEYER 71 @ DIMOND AK FRED MEYER 72788 - FRED MEYER 11 @ NORTHERN LIGHT AK FRED MEYER 72946 - FRED MEYER 17 @ SOLDOTNA AK FRED MEYER 72975 - FRED MEYER 224 @ FAIRBANKS AK FRED MEYER 72980 - FRED MEYER 671 @ PALMER AK FRED MEYER 79324 - FRED MEYER 158 @ JUNEAU AK FRED MEYER Fred Meyer-Anchorage East #18 AK HMS HOST 75697 - HMS HOST @ ANC 75697 AK HMS HOST 75988 - HMS HOST @ ANC 75988 AK SAFEWAY 12449 - SAFEWAY 1813 @ ANCHORAGE AK SAFEWAY 15313 - SAFEWAY 1739 @ PALMER AK SAFEWAY 3513 - SAFEWAY 1809 @ ANCHORAGE DEBARR RD AK SAFEWAY 4146 - SAFEWAY 1811 @ WAILLA AK SAFEWAY 74265 - SAFEWAY 1807 @ ALASKA EAGLE AK SAFEWAY 74266 - SAFEWAY 1817 @ MULDOON AK SAFEWAY 74283 - SAFEWAY 1820 JUNEAU AK SAFEWAY 74352 - SAFEWAY 2628 @ ABBOTT LOOP AK SAFEWAY 74430 - SAFEWAY 1805 @ AURORA AK SAFEWAY 74452 - SAFEWAY 3410 @ FAIRBANKS AK SAFEWAY 74474 - SAFEWAY 1090 @ KODIAK AK SAFEWAY 74640 - SAFEWAY 1818 @ KETCHIKAN AK SAFEWAY 74695 - SAFEWAY 548 @ SOLDOTNA AK SAFEWAY 74706 - SAFEWAY 2728 @ SEWARD AK SAFEWAY 74917 - SAFEWAY 1832 @ HOMER AK SAFEWAY 79549 - SAFEWAY 520 @ ANCHORAGE AK SAFEWAY 79664 - SAFEWAY 1812 @ ANCHORAGE -

Report: Brownfield Credit Report

BROWNFIELD REDEVELOPMENT TAX CREDIT On-site Groundwater DEC Site Preparation Component Tangible Property Component Remediation Component Taxpayer Name Project Site Name Region County Municipality En-Zone Costs Credit Costs Credit Costs Credit Total Costs Total Credit 2009 Tax Year CONSOLIDATED EDISON, INC. C231047 Astor Substation 2 New York Manhattan No 15,444,976 2,162,297 76,422,001 10,699,080 - 91,866,977 - 12,861,377 2010 Tax Year EMPIRE GEN HOLDINGS, INC.1 C442035 BASF Corporation South 40 Site 4 Rensselaer Rensselaer No 44,326,383 5,319,166 679,606,248 81,552,750 - 723,932,631 - 86,871,916 LOWE'S HOME CENTERS, INC. C734103 Midler City Industrial Park 7 Onondaga Syracuse No - - 19,081 2,289 - - 19,081 2,289 THE WIRE MILL, LLC C360065 Former Hudson Wire Co. 3 Westchester Ossining Yes - - 213,593 38,447 - - 213,593 38,447 2011 Tax Year COLLINS YONKERS II, LLC C360071 Yonkers Parcels B and C 3 Westchester Yonkers Yes - - 154,783 27,861 - - 154,783 27,861 REHC 5, LLC C907029 Former Ames / Hills Plaza 9 Chautauqua Jamestown Yes - - 3,413 614 - - 3,413 614 GERMANOW-SIMON CORPORATION C828117 Ward Street Site 8 Monroe Rochester Yes - - 266,441 53,288 - - 266,441 53,288 HYDRO-AIR COMPONENTS INC. C915204 Steelfields Area IV 9 Erie Buffalo No - - 324,687 38,962 - - 324,687 38,962 NORAMPAC INDUSTRIES INC. C915200 Former NL Industries Foundry 9 Erie Cheektowaga No 49,915 5,990 - - - - 49,915 5,990 FLUSHING TOWN CENTER, LP C241078, C241051, C241079 Flushing Industrial Park 2 Queens Queens No - - 52,430,905 5,243,091 - 52,430,905 - 5,243,091 RELATED RETAIL, LP2 C203015 Gateway Center at Bronx Terminal Market, Eastern 2 Bronx Bronx No - - N/A 22,443 - - - 22,443 NIAGARA TRANSFORMER CORP. -

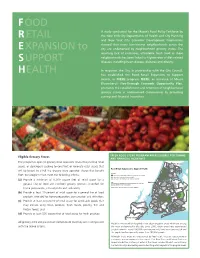

Food Retail Expansion to Support Health, Or FRESH Program

FOOD A study conducted for the Mayor’s Food Policy Taskforce by RETAIL the New York City Departments of Health and City Planning and New York City Economic Development Corporation showed that many low-income neighborhoods across the EXPANSIO N to city are underserved by neighborhood grocery stores. The resulting lack of nutritious, affordable fresh food in these neighborhoods has been linked to higher rates of diet-related SUPPORT diseases, including heart disease, diabetes and obesity. HEALTH In response, the City, in partnership with the City Council, has established the Food Retail Expansion to Support Health, or FRESH program. FRESH , an initiative of Mayor Bloomberg’s Five-Borough Economic Opportunity Plan , promotes the establishment and retention of neighborhood grocery stores in underserved communities by providing zoning and financial incentives. Eligible Grocery Stores FRESH FOOD STORE PROGRAM AREAS ELIGIBLE FOR ZONING AND FINANCIAL INCENTIVES The program is open to grocery store operators renovating existing retail The Bronx space, or developers seeking to construct or renovate retail space that Food Retail Expansion to Support Health will be leased by a full-line grocery store operator. Stores that benefit Legend from the program must meet the following criteria: Area where zoning and discretionary tax incentives are available Area where zoning incentives are available (a) Provide a minimum of 6,000 square feet of retail space for a Area where discretionary tax incentives are available Note: Manhattan Tax incentives are discretionary and will be assessed on a per case general line of food and nonfood grocery products intended for basis for eligibility in the FRESH program. -

Ownership Requests Proposals 7-11 East 115Th

7-11 EAST 115TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10029 54,496 BSF As-of-Right, 88,556 BSF w/ Community Facility, Development Site | FOR SALE PROPERTY INFORMATION Block / Lot 1621 / 7 Lot Dimensions 135' x 100.92' Lot Size 13,624 Sq. Ft. (Approx.) Zoning R7-2 FAR 4.00 FAR w/ Community Facility 6.50 Buildable Area (as-of-right) 54,496 Sq. Ft. (Approx.) Buildable Area (w/ Community Facility) 88,556 Sq. Ft. (Approx.) East 116 Assesment (19/20) $504,540 th Street Real Estate Taxes (19/20) $53,047 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS Avenue th 5 • EFFICIENT RECTANGULAR LAYOUT East 115 • SUBSTANTIAL LOT AREA OF 13,624 SQ. FT. th Street Madison Avenue • EXTENSIVE FRONTAGE OF 135’ • LARGE COMMUNITY FACILITY BONUS - 88,558 BUILDABLE SQ. FT. 54,496 88,556 135' X 100.92' EAST HARLEM Buildable SF (as-of-right) Buildable SF (w/ Community Facility) Lot Dimensions Location PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Ariel Property Advisors is pleased to present 7-11 East 115th Street, a 135’ wide The asset is located close to the border between East and Central Harlem, in the development site located on the north side of East 115th Street between Fifth heart of rapidly expanding neighborhoods, where the area has demonstrated Avenue and Madison Avenue in East Harlem. various new residential and condominium projects since the recent rezoning took place. Various completed condominium developments are achieving Zoned R7-2 (4.00 FAR – Wide Street), the site permits approximately 54,496 condo sellouts above $1,000 per square foot. Transportation options are also in buildable square feet (as-of-right) and approximately 88,556 buildable square feet abundance, providing access to lower Manhattan via the 2, 3 and 6 trains at the with community facility bonus, suitable for a large-scale residential development.