Why Speak Quechua? : a Study of Language Attitudes Among Native Quechua Speakers In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

Language Classification in the Ethnologue and Its Consequences (Paper)

Sarah E. Cornwell The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada Language Classification in The Ethnologue and its Consequences (Paper) Abstract: The Ethnologue is a widely used classificatory standard for the world’s 7000+ natural languages. However, the motives and processes used by The Ethnologue’s governing body, SIL International, have come under criticism by linguists. This paper investigates how The Ethnologue answers the question “What is a language?” through the theoretical lens presented by Bowker and Star in Sorting Things Out (1999) and presents some consequences of those classificatory decisions. 1. Introduction Language is central to human culture and experience. It is the central core of our communicative capacity, running through all media of communication. Due to this essential role, there is a need to classify and count languages and their speakers1. Governments need to communicate with citizens, libraries need to catalogue books by language, and search engines need to return webpages in the appropriate language for each searcher. For these reasons among others, there is a strong institutional need for a standardized classification structure and labelling system for languages. The most widespread current classificatory infrastructure for languages is based on The Ethnologue. This essay will critically evaluate The Ethnologue using the Foucauldian theory developed for investigating classification structures by Bowker and Star (1999) in Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences. 2. The Ethnologue The Ethnologue is a catalogue of all the world’s languages. First compiled in 1951, The Ethnologue is currently in its 20th edition and contains descriptions of 7099 living languages (2017). Since 1997, The Ethnologue has been available freely online and widely accessible (Simons & Fennig, 2017). -

Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras Twentieth Edition Data

Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras Twentieth edition data Gary F. Simons and Charles D. Fennig, Editors Based on information from the Ethnologue, 20th edition: Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2017. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twentieth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online: http://www.ethnologue.com. For personal use only Permission to distribute or reuse this work (in whole or in part) may be obtained through the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com. SIL International, 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road, Dallas, Texas 75236-5699 USA Web: www.sil.org, Phone: +1 972 708 7404, Email: [email protected] Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras 2 Contents List of Abbreviations 3 How to Use This Digest 4 Country Overview 6 Language Status Profile 7 Statistical Summaries 8 Alphabetical Listing of Languages 11 Language Map 14 Languages by Population 15 Languages by Status 16 Languages by Department 18 Languages by Family 19 Language Code Index 20 Language Name Index 21 Bibliography 22 Copyright © 2017 by SIL International All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, redistributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of SIL International, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews. Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras 3 List of Abbreviations A Agent in constituent word order alt. alternate name for alt. dial. alternate dialect name for C Consonant in canonical syllable patterns CDE Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960) Class Language classification CPPDCE Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) CSICH Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) dial. -

Contact Languages Around the World and Their Levels of Endangerment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Vol. 12 (2018), pp. 53–79 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24764 Revised Version Received: 23 Jan 2017 Contact languages around the world and their levels of endangerment Nala H. Lee National University of Singapore This paper provides an up-to-date report on the vitality or endangerment status of contact languages around the world, including pidgins, creoles, and mixed lan- guages. By utilizing information featured in the Endangered Languages Project and the Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Languages online portals, 96 contact languages are assessed on the Language Endangerment Index, a method of assessment that is based on four factors including intergenerational transmission, absolute num- ber of speakers, speaker number trends, and domains of use. Results show that the contact languages are most at risk with respect to intergenerational transmis- sion and domains of use. This is explained by the social and historical nature of contact languages. Overall results further raise the concern that the proportion of pidgins, creoles and mixed languages at some level of risk is extremely high. Rea- sons are provided for why linguists should be concerned about the endangerment of these languages. 1. Introduction1 While the language endangerment problem has been generally well- highlighted in linguistics, the endangerment of contact languages has not received the same level of attention. Krauss (1992) postulates that at least half and possibly as much as 90% of the world’s languages will no longer be spoken by the end of the present century, while a more recent empirical study estimates a slightly less catas- trophic rate of loss, at one language every three months (Campbell et al. -

Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College M.Ed. In TESL Program Language Group Specific Informational Reports Produced by Graduate Students in the M.Ed. In TESL Program In the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development Language Group: Quechua Author: Laura E. Faria Program Contact Person: Nancy Cloud ([email protected]) Language Report: Quechua Laura E. Faria TESL 539 Spring 2012 Snapshot of Quechua: Where is it spoken? • Quechua is the language & Quichua are the people • The Quichua are one of the largest indigenous populations in the world. (UNHCR, 2012) • 8+ million Quechua speakers in South America (Rosenfelder) • Quechua is a family of 40+ related languages based around the Andes Mountains (SIL International, 2012) quechuas.net www.witiger.com Snapshot of Quechua: Who Speaks It? • Quechua is spoken by the indigenous populations of Ecuador, Peru & Bolivia • The Quichua are a colorful, rugged, mountain people. • Quechua is a family of 40+ related languages o A family of languages (not dialects nor varieties) o Not all Quechua languages are similar - some differ immensely Quechua family living in the mountains (Quilotoa, Ecuador). (Heggarty, 2006) Dancing in typical, brightly colored clothing during the "Mama Negra" Quichua celebration & parade (Latacunga, Ecuador). Photos taken by author. Snapshot of Quechua: History • Quechua's origins began +/- 2000 years ago in Ancash, Peru (1000 years before The Incas) (Heggarty, 2006) Over the centuries, Quechua changed & evolved: Geographic expansion - • The Andes Mountains • north to Ecuador & south east to Bolivia Today, Quechua in Ecuador and Bolivia differ so greatly that indigenous from the 2 countries would struggle to communicate. (Heggarty, 2006) www.oxfordreference.com Shapshot of Quechua: History • Eventually, Quechua migrated south through Bolivia to northern Argentina. -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

ISO 639-3 New Code Element Request 2009-080 Cmd

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for New Language Code Element in ISO 639-3 This form is to be used in conjunction with a “Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code” form Date: 2009-7-28 Name of Primary Requester: Chuck Fennig E-mail address: editor_ethnologue at sil dot org Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: Associated Change request number : 2009-080 (completed by Registration Authority) Tentative assignment of new identifier : cmd (completed by Registration Authority) PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set. Use Shift-Enter to insert a new line in a form field (where allowed). 1. NAMES and IDENTIFICATION a) Preferred name of language for code element denotation: Moundadan Chetty b) Autonym (self-name) for this language: c) Common alternate names and spellings of language, and any established abbreviations: Moundan Chetty, Mandadan Chetty, Mamundadan Chetty. The name Moundadan Chetty was reported as coined by the British and a "corrupted" form of Mountain Chetty. d) Reason for preferred name: Most popular name in published sources (Government listings, Anthropological researches etc). e) Name and approximate population of ethnic group or community who use this language (complete individual language currently in use): Only one community use this language. Same name for both language and people group. Population is about 5,400 (report from community leader). Generall, the whole population is poor and only 10 people were reported as university graduates. f) Preferred three letter identifier, if available: Your suggestion will be taken into account, but the Registration Authority will determine the identifier to be proposed. -

The Arabic Language: a Latin of Modernity? Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics Volume 11 Issue 2 DOI 10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006 The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity? Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews Abstract Standard Arabic is directly derived from the language of the Quran. The Ara- bic language of the holy book of Islam is seen as the prescriptive benchmark of correctness for the use and standardization of Arabic. As such, this standard language is removed from the vernaculars over a millennium years, which Arabic-speakers employ nowadays in everyday life. Furthermore, standard Arabic is used for written purposes but very rarely spoken, which implies that there are no native speakers of this language. As a result, no speech com- munity of standard Arabic exists. Depending on the region or state, Arabs (understood here as Arabic speakers) belong to over 20 different vernacular speech communities centered around Arabic dialects. This feature is unique among the so-called “large languages” of the modern world. However, from a historical perspective, it can be likened to the functioning of Latin as the sole (written) language in Western Europe until the Reformation and in Central Europe until the mid-19th century. After the seventh to ninth century, there was no Latin-speaking community, while in day-to-day life, people who em- ployed Latin for written use spoke vernaculars. Afterward these vernaculars replaced Latin in written use also, so that now each recognized European lan- guage corresponds to a speech community. -

Fusion, Exponence, and Flexivity in Hindukush Languages

Fusion, exponence, and flexivity in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Hanna Rönnqvist Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Master 30 HE credits General Linguistics Spring term 2015 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examiner: Henrik Liljegren Fusion, exponence, and flexivity in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Hanna Rönnqvist Abstract Surrounding the Hindukush mountain chain is a stretch of land where as many as 50 distinct languages varieties of several language meet, in the present study referred to as “The Greater Hindukush” (GHK). In this area a large number of languages of at least six genera are spoken in a multi-linguistic setting. As the region is in part characterised by both contact between languages as well as isolation, it constitutes an interesting field of study of similarities and diversity, contact phenomena and possible genealogical connections. The present study takes in the region as a whole and attempts to characterise the morphology of the many languages spoken in it, by studying three parameters: phonological fusion, exponence, and flexivity in view of grammatical markers for Tense-Mood-Aspect, person marking, case marking, and plural marking on verbs and nouns. The study was performed with the perspective of areal typology, employed grammatical descriptions, and was in part inspired by three studies presented in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS). It was found that the region is one of high linguistic diversity, even if there are common traits, especially between languages of closer contact, such as the Iranian and the Indo-Aryan languages along the Pakistani-Afghan border where purely concatenative formatives are more common. -

Cultural and Linguistic Guidelines for Language Evaluation of Arab-American

Cultural and linguistic guidelines for language evaluation of Arab-American children using the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF) Reference this material as: Khamis-Dakwar,R., Al-Askary,H., Benmamoun,A., Ouali,H., Green,H., Leung,T., & Al-Asbahi,K. (2012, September 30). Cultural and linguistic guidelines for language evaluation of Arab-American children using the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF).Available from doi:xxxxx Copyright © 2012 Reem Khamis-Dakwar. All rights reserved Part I: The Cultural and Linguistic Background of Arab-Americans Introduction Based on the 2000 census, Arab Americans comprise 0.42% of the population in the United States (U.S.). The Arab-American population in the United States has been showing a steady increase since the 1980s (US. Bureau of the Census, 2005)1. Similar to other minority populations in the U.S., there has been a corresponding increase in the number of children referred for language assessment from this specific cultural and linguistic background. It is one of the top ten languages among English Language Learners (LLEs) in the U.S. (Batalova & Margie, 2010). Arab-Americans, as part of the diverse Arab population, compose a heterogeneous group; they come to the U.S. from countries in the North African region (such as Morocco), the Mediterranean region (such as Jordan), or the Arab Gulf region (such as Qatar) (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005) and may belong to a variety of religious faiths such as Islam, Christianity, Druze or Judaism. Despite these differences, Arab- Americans share historical memories, cultural values, cultural practices and Arabic as a native language 2(Khamis-Dakwar & Froud, 2012). -

Linguistic Repertoire and Sociolinguistic Contexts for Acquisition of Burushaski and Other Languages by Burushos of Kashmir

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2014): 5.611 Linguistic Repertoire and Sociolinguistic Contexts for Acquisition of Burushaski and Other Languages by Burushos of Kashmir Sabba Mushtaq University of Kashmir, Dept of Linguistics, Hazratbal, Srinagar, Kashmir, India Abstract: Burushaski, Pashto, Dardi and Gojri are regarded as minority languages as their speakers are demographically lower in number in Jammu and Kashmir and the natives of these languages use Kashmiri or Urdu in formal domains. Burushaski, also known by the names of Boorishki, Brugaski, Kanjut, Werchikwar and Mishaski is a language isolate spoken by some 87,000 Burusho people in Hunza, Nagar and Yasin area of Northern Pakistan. Linguistically, Burushaski has been termed as a language isolate because it does not characterize the genetic relationship with the surrounding language families like Indic, Sino-Tibetan, Dardic etc. Ethnologue (2005) mentions Burushaski speakers in India but does not provide about the specific information about the number of speakers and their exact location. According to the members of this speech community 300-350 Burushos live in Srinagar. Burushaski speakers of Jammu and Kashmir are settled in and around a small locality by the foothills of Hariparbat in Srinagar, the capital of Jammu and Kashmir. The locality is known as Mohalla Azur Khan, named after Raja Azur Khan. Jammu and Kashmir Burushos are also reported to live in Tral (Pulwama), Batamaloo, and Dandusa in Bemina area of Srinagar. The present paper aims to study the sociolinguistic context for acquisition of Burushaski and other languages known to Burushos of Kashmir. -

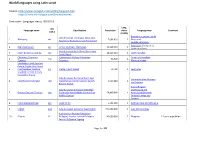

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11.