Christoph Bode, Rainer Dietrich Future Narratives Narrating Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart-Shaped Box Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HEART-SHAPED BOX PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joe Hill | 416 pages | 01 May 2008 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575081864 | English | London, United Kingdom Heart-shaped Box PDF Book It seemed like Hill just wanted to quickly wrap it up, no matter how many questions it either raised or left unanswered. A good old fashioned ghost story. View all 13 comments. He told biographer Michael Azerrad , "Anytime I think about it, it makes me sadder than anything I can think of. US Alternative Songs Billboard [2] [3]. October 16, Just hate our MC and pray that Georgia makes it out with the rest of us. Official Charts Company. The characters are unlika I had pretty big expectations for this novel, since it was somewhat of a happening in the horror genre and was praised by writers such as Harlan Coben and Neil Gaiman. The ghost in this story is Liam Neeson of Ghosts. I'm going to keep this spoiler free, but if you enjoyed NOS4A2, you will probably like this one as well. Thanks for telling us about the problem. New York City: Time, Inc. Unf Imagine a ghost! Aging rock star Judas Coyne spends his retirement collecting morbid memorabilia, including a witch's confession, a real snuff film and, after being sent an email directly about the item online, a dead man's funeral suit. Joe Hill surprised me with his clever plot and seemingly unlovable characters, I was turning the pages like there was no tomorrow for the last pages and didn't guess the ending. We sing together. Read more This book sucks. -

Program Book

Thank you to our sponsors: Presenting Sponsor: Supporting Sponsors: Additional support from Struck Catering. Thank you to our sponsors: Presenting Sponsor: mechanics hall worcester, ma Supporting Sponsors: Additional support from Struck Catering. NEFA’S IDEA SWAP You put creativity fi rst. Idea Swap is NEFA’s annual event contents that provides opportunities for New 2 England-based nonprofit presenting schedule organizations to network and share 4 project ideas that may qualify for project presentations: funding from NEFA’s Expeditions part 1 grant program. 7 project presentations: Expeditions grants are made to part 2 nonprofit organizations in New 9 England and support the tour more project ideas planning or touring of high quality and innovative performing arts projects. This booklet includes projects submitted as of October 20, 2014, #NEFAIdeaSwap which have the potential to tour New We put you fi rst. England. These and other projects submitted after press time can be contact Eastern Bank is proud to support the found on nefa.org. Presentation New England Foundation for the Arts. at the Idea Swap or inclusion in adrienne petrillo this booklet does not guarantee program manager Expeditions funding support. 617.951.0010 x527 [email protected] For more information about NEFA’s daniela jacobson Expeditions program or the Idea program coordinator Swap, please visit www.nefa.org or 617.951.0010 x528 call 617.951.0010 x527. [email protected] Member FDIC hereyourefi rst.com 1 schwanze-beast schedule Sara Coffey | Vermont Performance Lab 9:30am–10:00am -

View Our Annual Review 2017

Annual Review 2017 1 We are one of Britain’s leading building conservation charities. With the help of supporters and grant- In 2017: making bodies we save historic buildings in danger of being lost forever. We carefully restore such 68,055 ‘Landmarks’ and offer them a new future by making guests stayed them available for self-catering holidays. The lettings in Landmarks income from the 200 extraordinary buildings in our care supports their maintenance and survival in our landscape, culture and society. 44 charities benefited from free breaks 15,087 visitors came along on open days 4,651 people donated to support our work PATRON TRUSTEES HRH The Prince of Wales Neil Mendoza, Chairman Dame Elizabeth Forgan Dr Doug Gurr DIRECTOR John Hastings-Bass At Tangy Mill in Kintyre Dr Anna Keay Charles McVeigh III Landmarkers live amongst Pete Smith the carefully preserved Martin Stancliffe FSA Dip Arch RIBA original hoisting and Sarah Staniforth CBE grinding machinery. 3 Our restoration of Purton Green, Within touching distance of the past Suffolk, in 1970-71 rescued it from the brink of ruination. A nation’s heritage not only illuminates its past but has the power to shape its future. That this charity has saved some 200 often crumbling structures has only been possible because Landmark’s supporters believe in a building’s potential. Most recently the Heritage Lottery Fund granted half of the £4.2m needed to save Llwyn Celyn, our medieval house in the Black Mountains. We are also grateful to specialist insurer, Ecclesiastical, who donated £200,000 to revive Cobham Dairy. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

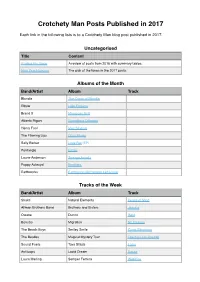

Crotchety Man Posts Published in 2017

Crotchety Man Posts Published in 2017 Each link in the following lists is to a Crotchety Man blog post published in 2017. Uncategorised Title Content Finding His Voice A review of posts from 2016 with summary tables. New Year Honours The pick of the tunes in the 2017 posts. Albums of the Month Band/Artist Album Track Blondie The Curse of Blondie Elbow Little Fictions Brand X Moroccan Roll Alberto Rigoni Something Different Henry Fool Men Singing The Flaming Lips Ozcy Mlody Sally Barker Love Rat (EP) Pentangle Finale Laurie Anderson Strange Angels Poppy Ackroyd Feathers Earthworks Earthworks/All Heaven Let Loose Tracks of the Week Band/Artist Album Track Shakti Natural Elements Peace of Mind Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters Jessica Owane Dunno Rekt Bonobo Migration No Reason The Beach Boys Smiley Smile Good Vibrations The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour The Fool On The Hill Sound Poets Tavs Stāsts Laiks Antiloops Lucid Dream Sasse Laura Marling Semper Femina Wild Fire Tracks of the Week Band/Artist Album Track Shirley Bassey Shirley/Let’s Face the Music What Now My Love? Penguin Café The Imperfect Sea Cantorum Depeche Mode Spirit Where’s the Revolution? Lana Del Rey Lust for Life Love Colin Hodgkinson The Bottom Line Thight Lines and Screaming Reels Paul Weller Jawbone Bottle Bob Marley Uprising Redemption Song Pretenders Pretenders Brass In Pocket Rick Wakeman Piano Portraits Summertime Yazz Wanted Fine Time London Grammar Truth Is A Beautiful Thing Oh Woman, Oh Man Bruce Springsteen Magic Magic Fairport Convention Unhalfbricking Autopsy Marsha Hunt - Walk On Gilded Splinters Murray Gold Doctor Who (Original Television Doctor Who Soundtrack) The Script #3 Hall of Fame Radiohead OK Computer OKNOTOK 1997 2017 I Promise Avi Avital, Omer Avital, et al Avital Meets Avital Zamzama The Verve Urban Hymns Weeping Willow XTC Drums and Wires Making Plans for Nigel Wishbone Ash Argus Blowin’ Free King Crimson Islands Sailor’s Tale Turin Brakes Ether Song Pain Killer (Summer Rain) Future Islands The Far Field Cave The Byrds Mr. -

Worldcharts TOP 200 + Album TOP 20 Vom 27.02.2017

CHARTSSERVICE – WORLDCHARTS – TOP 200 SINGLES NO. 897 – 27.02.2017 PL VW WO PK ARTIST SONG 1 1 8 1 ED SHEERAN shape of you 2 2 6 2 CHAINSMOKERS paris 3 3 12 2 ZAYN & TAYLOR SWIFT i don't wanna live forever (fifty shades darker) 4 26 3 4 KATY PERRY ft. SKIP MARLEY chained to the rhythm 5 4 18 1 CLEAN BANDIT ft. SEAN PAUL & ANNE-MARIE rockabye 6 5 14 2 WEEKND ft. DAFT PUNK i feel it coming 7 7 5 7 MARTIN GARRIX & DUA LIPA scared to be lonely 8 6 8 5 ED SHEERAN castle on the hill 9 8 23 1 WEEKND ft. DAFT PUNK starboy 10 9 28 9 RAG'N'BONE MAN human 11 10 20 1 BRUNO MARS 24k magic 12 89 2 12 KYGO & SELENA GOMEZ it ain't me 13 15 6 13 LUIS FONSI ft. DADDY YANKEE despacito 14 25 8 14 JAX JONES & RAYE you don't know me 15 11 19 2 MAROON 5 ft. KENDRICK LAMAR don't wanna know 16 13 4 13 MAJOR LAZER ft. PARTYNEXTDOOR & NICKI MINAJ run up 17 12 11 7 STEVE AOKI & LOUIS TOMLINSON just hold on 18 14 15 14 MACHINE GUN KELLY x CAMILA CABELLO bad things 19 29 3 19 IMAGINE DRAGONS believer 20 16 14 16 SEAN PAUL ft. DUA LIPA no lie 21 17 30 1 CHAINSMOKERS ft. HALSEY closer 22 20 16 19 SHAKIRA ft. MALUMA chantaje 23 18 13 12 ROBIN SCHULZ & DAVID GUETTA ft. CHEAT CODES shed a light 24 21 24 11 JAMES ARTHUR say you won't let go 25 22 17 22 STARLEY call on me 26 19 12 16 ALAN WALKER alone 27 23 23 3 CALVIN HARRIS my way 28 32 5 28 JULIA MICHAELS issues 29 24 30 2 DJ SNAKE ft. -

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2Pac Thug Life

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2pac Thug Life - Vol 1 12" 25th Anniverary 20.99 2pac Me Against The World 12" - 2020 Reissue 24.99 3108 3108 12" 9.99 65daysofstatic Replicr 2019 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest We Got It From Here Thank You 4 Your Service 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm 12" Reissue 26.99 Abba Live At Wembley Arena 12" - Half Speed Master 3 Lp 32.99 Abba Gold 12" 22.99 Abba Abba - The Album 12" 12.99 AC/DC Highway To Hell 12" 20.99 Ace Frehley Spaceman - 12" 29.99 Acid Mothers Temple Minstrel In The Galaxy 12" 21.99 Adele 25 12" 16.99 Adele 21 12" 16.99 Adele 19- 12" 16.99 Agnes Obel Myopia 12" 21.99 Ags Connolly How About Now 12" 9.99 Air Moon Safari 12" 15.99 Alan Marks Erik Satie - Vexations 12" 19.99 Aldous Harding Party 12" 16.99 Alec Cheer Night Kaleidoscope Ost 12" 14.99 Alex Banks Beneath The Surface 12" 19.99 Alex Lahey The Best Of Luck Club 12" White Vinyl 19.99 Algiers There Is No Year 12" Dinked Edition 26.99 Ali Farka Toure With Ry Cooder Talking Timbuktu 12" 24.99 Alice Coltrane The Ecstatic Music Of... 12" 28.99 Alice Cooper Greatest Hits 12" 16.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" Dinked Edition 19.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" 18.99 Alloy Orchestra Man With A Movie Camera- Live At Third Man Records 12" 12.99 Alt-j An Awesome Wave 12" 16.99 Amazones D'afrique Amazones Power 12" 24.99 American Aquarium Lamentations 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Amy Winehouse Frank 12" 19.99 Amy Winehouse Back To Black - 12" 12.99 Anchorsong Cohesion 12" 12.99 Anderson Paak Malibu 12" 21.99 Andrew Bird My Finest Work 12" 22.99 Andrew Combs Worried Man 12" White Vinyl 16.99 Andrew Combs Ideal Man 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Andrew W.k I Get Wet 12" 38.99 Angel Olsen All Mirrors 12" Clear Vinyl 22.99 Angelo Badalamenti Twin Peaks - Ost 12" - Ltd Green 20.99 Ann Peebles Greatest Hits 12" 15.99 Anna Calvi Hunted 12" - Ltd Red 24.99 Anna St. -

Proquest Dissertations

Library and Archives Bibliotheque et l+M Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54229-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54229-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne sur la Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de la vie privee, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont ete enleves de thesis. -

BABY DRIVER One of the Year’S Best Movies

PACKED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE FULL LIST OF 2500+ CHANNELS Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the Digital Widescreen | October 2017 13th consecutive year! Cut to the chase in BABY DRIVER one of the year’s best movies © 2017 MARVEL NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCOct17EX2.indd 51 12/09/2017 16:51 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_60_OCTOBER17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 525 © 2017 Disney/Pixar© 2017 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel WATCH LIVE TV number into your handset, or use 2 3 Live news and sport the onscreen channel entry pad channels are 1 3 available on Swipe left and Search for Move around most fl ights. right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games Find out Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad more on onscreen to and system on your handset page 9. -

FLANNERY O'connor and JAMES BALDWIN in GEORGIA Carole K. Harris in a Letter Often Quote

Carole K. Harris ON FLYING MULES AND THE SOUTHERN CABALA: FLANNERY O'CONNOR AND JAMES BALDWIN IN GEORGIA I believe that the truth of any subject only comes when all sides of the story are put together, and all their different readings make one new one. Each writer writes the missing parts of the other writer’s story. And the whole story is what I’m after. –Alice Walker, “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor”1 N a letter often quoted by scholars, Flannery O’Connor responds to her friend Maryat Lee, a social activist and playwright living in New York, Iwho wants to set up a meeting between O’Connor and James Baldwin: No I can’t see James Baldwin in Georgia. It would cause the great- est trouble and disturbance and disunion. In New York it would be nice to meet him; here it would not. I observe the traditions of the society I feed on — it’s only fair. Might as well expect a mule to fly as me to see James Baldwin in Georgia. (April 25, 1959, CW 1094-95) Although in 1959 Flannery O’Connor refused to meet James Baldwin in Georgia, her keen moral observations of southern manners, especially as they play out in relationships of power based on race, gender, and class, are oddly similar to his. By declining Lee’s invitation, O’Connor shows herself to be bound to the manners of her cultural environment at a par- ticular moment in history. O’Connor and Baldwin produced much of their major work in the years after Brown vs. -

Publishing Fellowship Report

PUBLISHING FELLOWSHIP REPORT Bronwyn Mehan Email: [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ______________________________________________ 4 Overview ______________________________________________________ 5 Scope of the Publishing Fellowship Research _________________________ 6 My Development As A Publisher/Producer ____________________________ 7 Developing Networking Skills________________________________________________ 7 Looking For Multi-platform Storytelling in New York _____________________________ 10 Looking for Literary Fiction Podcasts _________________________________________ 11 Explore Showcasing Opportunities _________________________________ 13 Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 13 Little Fictions @ QED _____________________________________________________ 13 Interview with Kambri Crew, Q.E.D, Astoria ___________________________________ 14 Funding Model and Loyalty System __________________________________________ 14 Local and Diverse _______________________________________________________ 15 Q.E.D – a model for commercially-run or cost-recovery creative centres _____________ 16 Take-away # 1. Multi-platform producers need multi-purpose venues _______________ 17 Short Film Festivals ______________________________________________________ 18 Investigating Multi-Platform Publishing In New York ____________________ 20 About Newtown Literary Alliance ____________________________________________ 20 Funding Model __________________________________________________________ -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 3-1-2005 SFRA ewN sletter 271 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 271 " (2005). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 86. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/86 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #1TI IM./FeII.'lflJfth 1H§ Nonfiction Reriews: Ed McHnliaht Science Fiction Research fiction Reriews: Association Phlillip Snyder The SFRAReview (ISSN III 7HIS ISSUE: 1068-395X) is published four times a year by the Science Fiction Researc:hAs SFRA Business sociation (SFRA) and distributed to Editor's Message 2 SFRA members. Individual issues are not President's Message 2 for sale; however, starting with issue #256, all issues will be published to Minutes of the Executive Conference SFRA's website no less than 10 weeks after paper publication. For information Approaches to Teachini ... about the SFRA and its benefits, see the description at the back of this issue. For Le Guln's The Lathe of Heaven & a membership application, contact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or get one from Non Fiction Reviews the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. SFRA would like to thank the Univer A Sense of Wonder I I sity of Wisconsin-Eau Claire for its as Gernsback Days 12 sistance in producing the Review.