TIP 61 Behavioral Health Services for American Indian and Alask Natives Part 3: Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kickapoo Tribe by Jacob

Kickapoo Tribe by Jacob Questions and answers: Where did the tribe live? Where do the people live now? The Kickapoo Indian people are from Michigan and in the area of Great Lakes Regions. Most Kickapoo people still live in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. What did they eat? The Kickapoo men hunted large animals like deer. They also eat com, cornbread call "'pugna" and planted squash and beans. What did they wear? The women wore wrap around skirts. Men wore breechcloths with leggings. What special ceremonies did they have? The Kickapoo people were very spiritual and connected with animals and they had special ceremonies when it came to hunting. A display of lighting and thunder, usually in early February signifies the beginning of the New Year and hence the cycle of the ceremonies. Some of the ceremonies would be hand drum, dancing and singing. What kind of homes did they build? The Kickapoo people made homes called wickiups and Indian brush shelters. 5 Interesting Facts of the Kickapoo People: 1. Story telling is very important to the Kickapoo Indian culture. 2. Kickapoo hunters & warriors used spears, clubs, bows and arrows to hunt for food. 3. Ho (pronounced like the English word Hoe) is a friendly greeting. 4. Kepilhcihi (pronounced Kehpeeehihhih) means "thank you." 5. The Kickapoo children are just like us. They go to school, like to play and help around the house.. -

NARF Annual Report 2018(A)

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Director’s Report .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chairman’s Message ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Board of Directors and National Support Committee ........................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Preserving Tribal Existence .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Protecting Tribal Natural Resources .................................................................................................................................... 9 Promoting Human Rights .................................................................................................................................................... 17 Holding Governments Accountable .................................................................................................................................... 24 Developing Indian Law ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover cover next page > title: American Indian Holocaust and Survival : A Population History Since 1492 Civilization of the American Indian Series ; V. 186 author: Thornton, Russell. publisher: University of Oklahoma Press isbn10 | asin: 080612220X print isbn13: 9780806122205 ebook isbn13: 9780806170213 language: English subject Indians of North America--Population, America-- Population. publication date: 1987 lcc: E59.P75T48 1987eb ddc: 304.6/08997073 subject: Indians of North America--Population, America-- Population. cover next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/cover.html[1/17/2011 5:09:37 PM] page_i < previous page page_i next page > Page i The Civilization of the American Indian Series < previous page page_i next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/page_i.html[1/17/2011 5:09:38 PM] page_v < previous page page_v next page > Page v American Indian Holocaust and Survival A Population History Since 1492 by Russell Thornton University of Oklahoma Press : Norman and London < previous page page_v next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/page_v.html[1/17/2011 5:09:38 PM] page_vi < previous page page_vi next page > Page vi BY RUSSELL THORNTON Sociology of American Indians: A Critical Bibliography (With Mary K. Grasmick) (Bloomington, Ind., 1980) The Urbanization of American Indians: A Critical Bibliography (with Gary D. Sandefur and Harold G. Grasmick) (Bloomington, Ind., 1982) We Shall Live Again: The 1870 and 1890 Ghost Dance Movements as Demographic Repitalization (New York, 1986) American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman, 1987) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thornton, Russell, 1942 American Indian holocaust and survival. -

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments by Thomas J. Sloan, Ph.D. Kansas State Representative Contents Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments ....................................... 1 The Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas ..................... ................................................................................................................... 11 Prairie Band of Potawatomi ........................... .................................................................................................................. 15 Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska .............................................................................................................................. 17 Appendix: Constitution and By-Laws of the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas ..................................... .................. ............................................................................................... 19 iii Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments Overview of American Indian Law cal "trust" relationships. At the time of this writing, and Tribal/Federal Relations tribes from across the United States are engaged in a lawsuit against the Department of the Interior for At its simplest, a tribe is a collective of American In- mismanaging funds held in trust for the tribes. A fed- dians (most historic U.S. documents refer to "Indi- eral court is deciding whether to hold current and -

Great Falls Genealogy Library Current Collection October, 2019 Page 1 GFGS # Title Subtitle Author Co-Author Copyright Date

Great Falls Genealogy Library Current Collection October, 2019 GFGS # Title Subtitle Author Co-Author Copyright Date 1st Description 4859 Ancestral Lineages Seattle Perkins, Estelle Ruth 1956 WA 10748 ??Why?? Pray, Montana Doris Whithorn 1997 MT Historical & Genealogical Soc. of 3681 'Mongst the Hills of Somerset c.1980 PA Somerset Co.,Inc 5892 "Big Dreams in a Small Town" Big Sandy Homecoming 1995 1995 Homecoming Committee 1995 MT 7621 "Come, Blackrobe" De Smet and the Indian Tragedy Killoren, John J., S.J. 2003 Indians 10896 "Enlightened Selfishness": Montana's Sun River Proj Judith Kay Fabry 1993 MT 10312 "I Will Be Meat Fo My Salish"… Bon I. Whealdon Edited by Robert Bigart 2001 INDIANS 7320 "Keystone Kuzzins" Index Volume 1 - 8 Erie Society PA 10491 "Moments to Remember" 1950-1959 Decade Reunion University of Montana The Alumni Center 1960 MT 8817 "Our Crowd" The Great Jewish Families of New York Stephen Birmingham 1967 NEW YORK 8437 "Paper Talk" Charlie Russell's American West Dippie, Brian W. Editor 1979 MT 9837 "Railroads To Rockets" 1887-1962 Diamond Jubilee Phillips County, Montana Historical Book Committee 1962 MT 296 "Second Census" of Kentucky - 1800 Clift, G. Glenn c.1954 KY "The Coming Man From Canton": Chinese Exper. In 10869 Christopher W. Merritt 2010 MT MT 1862-1943 9258 "The Golden Triangle" Homesteaading In Montana Ephretta J. Risley 1975 MT 8723 "The Whole Country was…'One Robe'" The Little Shell Tribe's America Nicholas C. P. Vrooman 2012 Indians 7461 "To Protect and Serve" Memories of a Police Officer Klemencic, Richard "Klem" 2001 MT 10471 "Yellowstone Kelly" The Memoirs of Luther S. -

Cultural Implications of Being a Cross-Border Nation

The Kickapoo of Coahuila/Texas Cultural Implications Of Being a Cross-border Nation Elisabeth A. Mager Hois* Elisabeth Mager George White Water, war chief, in front of his summer house in El Nacimiento, Coahuila. rossborder indigenous nations like the O’odham Never theless, the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas (K ttt ) (Pápagos), Cucapá, and the Kickapoo of Coahuila/ reservation is a more powerful magnet, because they set up CTexas, living on both sides of the MexicoU.S. border a casino on that fe deral land and the U.S. federal govern and continually crossing it, are subject to severe cultural in ment awards them certain benefits as an officially recognized fluences by the U.S. Their economic future is north of the tribe. Therefore, the cultural influence on them from the border, and, in power terms, the intercultural relationship be U.S. nation is determinant. In contrast, the Kickapoo com tween Mexico and the U.S. is asymmetrical, since the United munity on the Mexican side serves mainly as a ceremonial States is a world power. In addition, certain privileges enjoyed center, although in recent years, the K ttt has invested a great by U.S.origin tribes facilitate crossborder migration and deal in the countryside in this area with the profits from the their intercultural contact with the two nationstates. Kickapoo Lucky Eagle Casino. Originally from the Great Lakes, the Kickapoo of Coa Thus, crossborder migration from Mexico to the United huil a/Texas have settlements on both sides of the border. States can be explained by the attraction of the latter’s eco n omy, which simultaneously benefits the community in Coa * Professor and researcher at the UNAM School of Higher Learning huila, particularly when the exchange rate for the U.S. -

Making Education Relevant for Contemporary Indian Youth: A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 353 090 RC 018 439 AUTHOR Chisholm, Anita; And Others TITLE Making Education Relevantfor Contemporary Indian Youth: A Handbook for CulturalCurriculum Developers Focusing on American Indian Tribesand Canadian First Nations. 1991 Edition. INSTITUTION Oklahoma Univ., Norman. AmericanIndian Inst. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 126p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052)-- Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Education;American Indians; *Canada Natives; *Cultural Education;*Curriculum Development; Educational Resources;Elementary Secondary Education; InstructionalMaterial Evaluation; Instructional Materials;*Multicultural Education; *Relevance (Education) ABSTRACT This guide was developedto assist American Indian and Canadian Native educators in developing culturalcurriculum materials for use in theclassroom. The purpose of developing authentic cultural materials is to enhance the educationalexperience of Indian students and White students. The guidecovers the following topics: (1) cultural curriculum development including goals of multicultural education andcultural learning;(2) format for cultural curriculum development; (3)writing specific and clear objectives for classroom instruction; (4) sample unitoutlines for curriculum development; (5) rules for effective, clearwriting; (6) interviewing techniques and example of a lesson preparedfrom an interview;(7) setting up curriculum teams; (8) scope andsequence of curriculum; (9) documenting cultural curriculumresources -

The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Written by Shirley E

THE EMIGRANT MÉTIS OF KANSAS: RETHINKING THE PIONEER NARRATIVE by SHIRLEY E. KASPER B.A., Marshall University, 1971 M.S., University of Kansas, 1984 M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1998 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2012 This dissertation entitled: The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative written by Shirley E. Kasper has been approved for the Department of History _______________________________________ Dr. Ralph Mann _______________________________________ Dr. Virginia DeJohn Anderson Date: April 13, 2012 The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Kasper, Shirley E. (Ph.D., History) The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Ralph Mann Under the U.S. government’s nineteenth century Indian removal policies, more than ten thousand Eastern Indians, mostly Algonquians from the Great Lakes region, relocated in the 1830s and 1840s beyond the western border of Missouri to what today is the state of Kansas. With them went a number of mixed-race people – the métis, who were born of the fur trade and the interracial unions that it spawned. This dissertation focuses on métis among one emigrant group, the Potawatomi, who removed to a reservation in Kansas that sat directly in the path of the great overland migration to Oregon and California. -

American Indians in Oklahoma OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT

American Indians in Oklahoma OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Nawa! That means hello in the Pawnee language. In Oklahoma, thirty-eight federally recognized tribes represent about 8 percent of the population. Most of these tribes came from places around the country but were removed from their homelands to Oklahoma in the nineteenth century. Their diverse cultures and rich heritage make Oklahoma (which combines the Choctaw words “okla” and “huma,” or “territory of the red people”) a special state. American Indians have impacted Oklahoma’s growth from territory to statehood and have made it into the great state it is today. This site allows you to learn more about American Indian tribes in Oklahoma. First, read the background pages for more information, then go through the biographies of influential American Indians to learn more about him or her. The activities section has coloring sheets, games, and other activities, which can be done as part of a group or on your own. Map of Indian Territory prior to 1889 (ITMAP.0035, Oklahoma Historical Society Map Collection, OHS). American Indians │2016 │1 Before European Contact The first people living on the prairie were the ancestors of various American Indian tribes. Through archaeology, we know that the plains have been inhabited for centuries by groups of people who lived in semi-permanent villages and depended on planting crops and hunting animals. Many of the ideas we associate with American Indians, such as the travois, various ceremonies, tipis, earth lodges, and controlled bison hunts, come from these first prairie people. Through archaeology, we know that the ancestors of the Wichita and Caddo tribes have been in present-day Oklahoma for more than two thousand years. -

NARF Annual Report 2019

The Native American Rights Fund Statement on Environmental Sustainability “It is clear that our natural world is undergoing severe, unsustainable and catastrophic climate change that adversely impacts the lives of people and ecosystems worldwide. Native Americans are especially vulnerable and are experiencing disproportionate negative impacts on their cultures, health and food systems. In response, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) is committed to environmental sustainability through its mission, work and organizational values. Native Americans and other indigenous peoples have a long tradition of living sustainably with the natural world by understanding the importance of preserving natural resources and respecting the interdependence of all living things. NARF embraces this tradition through its work and by instituting sustainable office practices that reduce our negative impact on our climate and environment. NARF is engaged in environmental work and has established a Green Office Committee whose responsibility is to lead and coordinate staff participa- tion in establishing and implementing policies and procedures to mini- mize waste, reduce energy consumption and pollution and create a health- ful work environment.” Tax Status: The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) is a nonprofit, char- itable organization incorporated in 1971 under the laws of the District of Columbia. NARF is exempt from federal income tax under the provisions of Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue code. Contributions to NARF are tax deductible. The Internal Revenue Service has ruled that NARF is not a "private foundation" as defined in Section 509(a) of the Internal Revenue Code. NARF was founded in 1970 and incorporated in 1971 in Washington, D.C. -

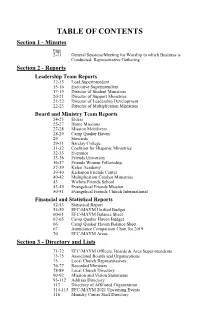

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 - Minutes Page 2-11 General Sessions/Meeting for Worship in which Business is Conducted: Representative Gathering Section 2 - Reports Leadership Team Reports 12-15 Lead Superintendent 15-16 Executive Superintendent 17-19 Director of Student Ministries 20-21 Director of Support Ministries 21-22 Director of Leadership Development 22-23 Director of Multiplication Ministries Board and Ministry Team Reports 24-25 Elders 25-27 Home Missions 27-28 Mission Mobilizers 28-29 Camp Quaker Haven 29 Stewards 29-31 Barclay College 31-32 Coalition for Hispanic Ministries 32-33 Everence 33-36 Friends University 36-37 Friends Women Fellowship 37-39 Kaleo Academy 39-40 Kickapoo Friends Center 40-42 Multiplication Catalyst Ministries 43 Wichita Friends School 43-49 Evangelical Friends Mission 50-51 Evangelical Friends Church Intermational Financial and Statistical Reports 52-53 Statistical Report 54-59 EFC-MAYM Unified Budget 60-61 EFC-MAYM Balance Sheet 62-65 Camp Quaker Haven Budget 66 Camp Quaker Haven Balance Sheet 67 Attendance Comparison Chart for 2019 70 EFC-MAYM Areas Section 3 - Directory and Lists 71-72 EFC-MAYM Officers, Boards & Area Superintendents 73-75 Associated Boards and Organizations 75 Local Church Representatives 76-77 Recorded Ministers 78-89 Local Church Directory 90-92 Mission and Vision Statements 93-112 Address Directory 113 Directory of Affiliated Organization 114-115 EFC-MAYM 2021 Upcoming Events 116 Ministry Center Staff Directory Minutes General Sessions EFC-MAYM Ministry Team Leader Gathering Via Zoom Friday, July 24, 2020 5:30 p.m. PRESENT: David Bailey, Robyn Burns, David Byrne, David Crisp, Manny Garcia, Diana Hoover, Dave Kingrey, Julie Kinser, Jeff Linville, Randy Little- field, Dennis McDowell, Mike Neifert, Jesse Penna, John Penrose, Diana Roe, Jenna Schmidt, Thayne Thompson, Jared Warner, Wanda Warner, David Wil- liams, Brad Wood, Lois Carr – Recording Clerk. -

NARF Legal Review Vol41no.2

NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND Land into Trust Litigation Ends Historic Victory for Alaska Tribes On August 15, 2016, Alaska Attorney General Jahna Lindemuth announced that the State of Alaska will not pursue further litigation in Alaska Native Community v. U.S. Secretary of the Interior. That case affirmed the ability of the Secretary of Interior to take land into trust on behalf of Alaska tribes and Alaska Natives, and also acknowledged the rights of Alaska tribes to be treated the same as all other federally recognized Tribes. The State’s decision to not seek Supreme Court review ends years of protracted litigation and ushers in a new era for Alaska tribes. “Trust land” refers to land held by the United States in trust for the benefit and use of an Indian tribe or individual. It contrasts with “fee land” or land held in “fee simple” which is the most common type of land ownership. Fee Land into Trust Litigation Ends land is property in which owners have complete Historic Victory for Alaska Tribes .......... page 1 ownership of the land and the home. Owners of “fee land” can sell or mortgage their land but NARF stands with remain subject to state taxation and debt obliga- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe...................... page 4 tions on their mortgage. Unlike fee land, trust Case Updates ............................................page 8 land is not subject to state taxation or debt fore- closure, and is considered “Indian Country” for National Indian Law Library ................ page 13 jurisdictional purposes. Indian Country includes all land within the limits of any Indian reservation Calling Tribes to Action! .....................