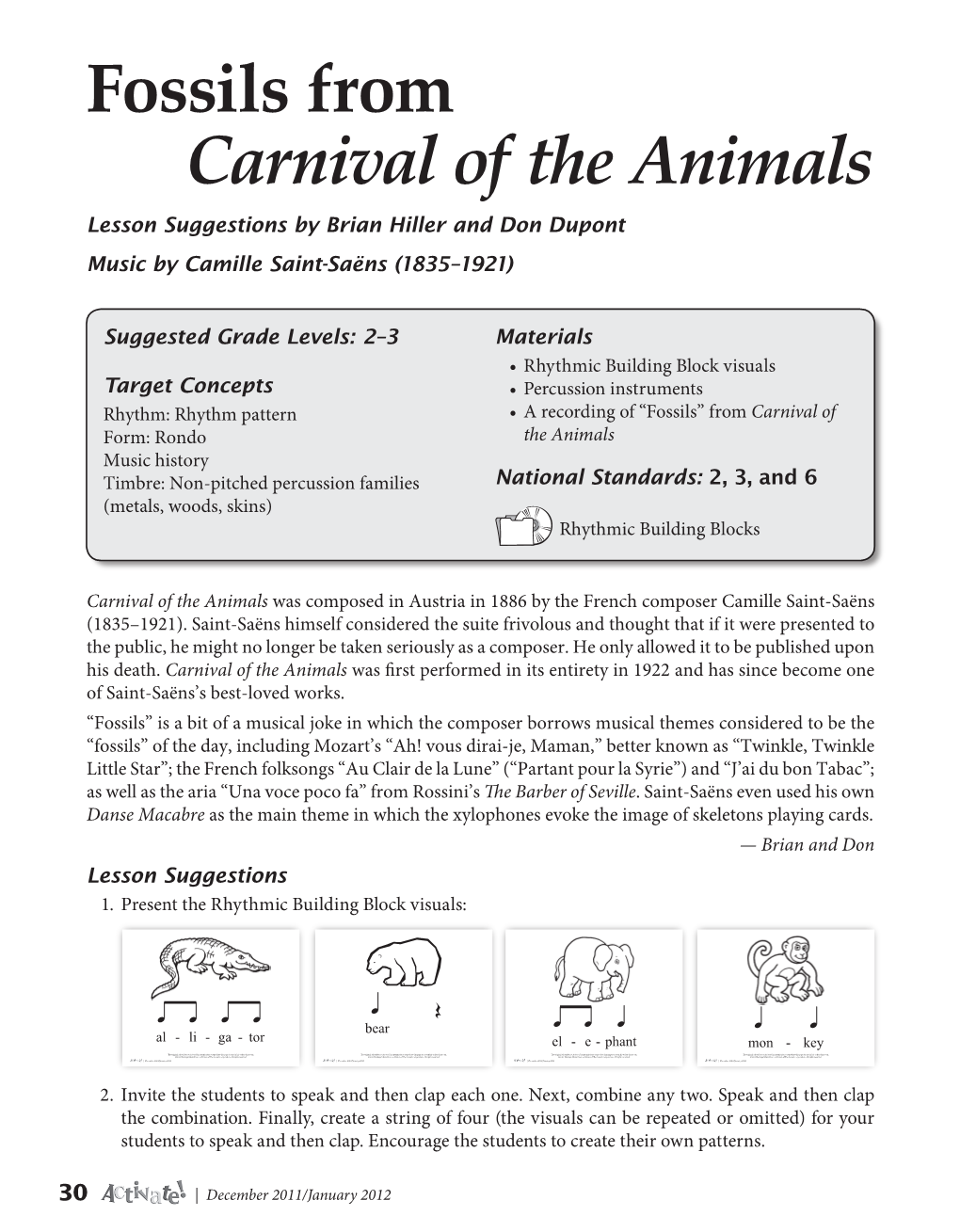

Fossils from Carnival of the Animals Lesson Suggestions by Brian Hiller and Don Dupont Music by Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lehrplan MAR 1998

Gymnasien des Kantons St.Gallen Lehrplan 2008/10 Allgemeiner Teil Seite 1 Lehrplan für das Gymnasium im Kanton St.Gallen Vom Erziehungsrat erlassen am 21. Juni 20061 Von der Regierung genehmigt am 4. Juli 20062 In Vollzug ab 1. August 20063 Allgemeiner Teil Funktionen des Lehrplans ................................................................................................................ 2 Bildungsziele und rechtliche Grundlagen ........................................................................................ 3 Rahmenlehrplan für die Maturitätsschulen ...................................................................................... 4 Struktur und Begriffe ....................................................................................................................... 6 Unterrichtsformen ............................................................................................................................ 7 Fachübergreifender Unterricht ......................................................................................................... 9 Stundentafel ................................................................................................................................... 10 Fachlehrpläne Grundlagenfächer / obligatorische Fächer GF 1 Deutsch .......................................................................................................................................... 12 GF 2 Zweite Landessprache ................................................................................................................... -

Grand Solo Op.14 & Rondo Op2. N3

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2017 Grand Solo Op.14 & Rondo Op2. N3: The Sonority of the Classical Era Hugo Maia Nogueira University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the History Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Maia Nogueira, Hugo, "Grand Solo Op.14 & Rondo Op2. N3: The Sonority of the Classical Era" (2017). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3007. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10986009 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRAND SOLO OP.14 & RONDO OP2. N3: THE SONORITY OF THE CLASSICAL ERA by Hugo Maia Nogueira Bachelor of Music Faculdade de Artes Alcântara Machado 2007 Teaching Licensure Centro Universitário Belas Artes 2010 Master of Music Azusa Pacific University 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2017 Copyright 2017 Hugo Maia Nogueira All Rights Reserved Doctoral Project Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas April 6, 2017 This doctoral project prepared by Hugo Maia Nogueira entitled Grand Solo Op.14 & Rondo Op2. -

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Clarinet Concerto in a Major, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 Mozart composed this concerto between the end of September and mid-November 1791, and it apparently was performed in Vienna shortly afterwards. The orchestra consists of two flutes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-nine minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was given at the Ravinia Festival on July 25, 1957, with Reginald Kell as soloist and Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra’s first subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on May 2, 1963, with Clark Brody as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on October 11 and 12, 1991, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra most recently performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 2001, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Andrew Davis conducting. This concerto is the last important work Mozart finished before his death. He recorded it in his personal catalog without a date, right after The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. The only later entry is the little Masonic Cantata, dated November 15, 1791. The Requiem, as we know, didn’t make it into the list. For decades the history of the Requiem was full of ambiguity, while that of the Clarinet Concerto seemed quite clear. But in recent years, as we learned more about the unfinished Requiem, questions about the concerto began to emerge. -

A BIOGRAPHY of JOSEPH MAURICE RAVEL by Matthew Dechirico

A BIOGRAPHY OF JOSEPH MAURICE RAVEL by Matthew DeChirico Joseph Maurice Ravel, who lived from March 1875 to December 1937 was a French composer born in the Basque region of France His mother of Basque-Spanish heritage from Madrid Spain had a strong influence on his life and his music. His father was a Swiss inventor and industrialist from France. Both parents provided a happy and stimulating life for Joseph and his younger brother. His parents encouraged his musical pursuits and sent him at age 14 to the Conservatoire de Paris first as a preparatory student and eventually as a piano major. Although intellectually bright and well read, he was not successful academically even as his musicianship matured. Considered “very gifted” he nevertheless was called “somewhat heedless” in his studies. He failed to meet the requirements of earning a competitive medal and was expelled. He returned three years later studying with Gabriel Faure focusing on composition rather than piano. He was again dismissed for having won neither the fugue nor the composition prize. He remained an auditor with Faure until he left the Conservatoire in 1903. During his years at the Conservatoire, Ravel tried numerous times to win the prestigious Prix de Rome but to no avail: he was probably considered too radical by the conservatives. Ravel’s “String Quartet in F” is now a standard work of chamber music, though at the time it was criticized and found lacking academically. His first significant work, “Habanera” for two pianos was later transcribed into the third movement of his “Rapsodie Espagnole”. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Binary & Ternary Forms

Binary & Ternary Forms Formal Element Review • Motive: A motive is the smallest recognizable musical idea. o labeled with lowercase letters starting at the end of the alphabet • Phrase: a relatively independent musical idea that moves towards a cadence as its goal; a complete musical thought o labeled with lowercase letters starting at the beginning of the alphabet o subphrase: a musical unit smaller than a phrase but still a coherent gesture o sentence: a particular type of phrase or phrase group with an internal structure of 1+1+2 • Period: a pair of phrases that specifically work together in an antecedent-consequent relationship o First phrase (antecedent) will have an inconclusive cadence (half cadence or IAC) o Second phrase (consequent) will have a conclusive cadence (usually a PAC) Formal Structures • Formal structures are larger sections of music made up of these formal elements (phrases, periods, etc.) o typically labeled with uppercase letters starting at the beginning of the alphabet • Each standard formal structures contains a specific pattern of these larger sections (with minor variations) Factors to Consider in Formal Analysis • Key areas: in which key a phrase or section starts and/or ends o closed vs. open sections a closed section is self-contained - ends in the same key in which it begins with a conclusive cadence an open section is not self-contained - ends in a different key or with an inconclusive cadence - often features a half-cadence, modulation to the dominant, or modulation to the relative major • Motivic use: similar or contrasting motivic use within phrases or sections • Formal elements: phrases, cadences, periods, etc. -

MAURICE RAVEL Miroirs (“Mirrors”) Work Composed: 1904–05 in Contrast to the Voluptuous, Sens

MAURICE RAVEL Miroirs (“Mirrors”) Work composed: 1904–05 In contrast to the voluptuous, sensuous and intentionally ambiguous music of Debussy, Ravel’s compositions are precise, clear in design and economical in scoring. Nonetheless, the music of both composers — and many strikingly similar titles — clearly shares an overlapping sensibility and sense of fantasy. Ravel presented his freshly minted piano score Miroirs (“Mirrors”) to his inner circle of artist friends known collectively as the Apaches, dedicating each movement to a specific member of the tight-knit group. The five-part suite reflects the gauzy evanescence of Debussy’s impressionism while paying homage to Liszt’s pianistic pyrotechnics. The influence of Debussy is felt immediately in the first movement, Noctuelles (“Night moths”). Schumann and other composers have rhapsodized about butterflies but Ravel, who always maintained a fascination for the outré, obviously delighted in the intentional grotesqueries evoked in the music. Not coincidentally, he dedicated this piece to Léon-Paul Fargue, who authored this phrase: “The owlet-moths fly clumsily out of the old barn to drape themselves round other beams.” Rapidly scurrying passagework vividly portrays the rapidly changing flight patterns of the winged insects. In the second piece, Oiseaux tristes (“Sad Birds”), dedicated to pianist Ricardo Viñes, Ravel sought to evoke “birds lost in the torpor of a dark forest during the hottest hours of the summer,” or so the composer explained. Even so, the textures are more crisply chiseled than one might expect from the descriptive explanation. Unlike his latter compatriot, Messiaen, Ravel does not imitate bird-song but conveys an unmistakable avian aura. -

Ravel's Sound

Ravel’s Sound: Timbre and Orchestration in His Late Works Jennifer P. Beavers NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.beavers.php KEYWORDS: Ravel, timbre, contour, magical effect, illusory instruments, timbrally marked form, sound object, auditory scene analysis, Pictures at an Exhibition, Boléro, Menuet antique, Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, Piano Concerto in G Major ABSTRACT: Ravel’s interwar compositions and transcriptions reveal a sophisticated engagement with timbre and orchestration. Of interest is the way he uses timbre to connect and conceal passages in his music. In this article, I look at the way Ravel manipulates instrumental timbre to create sonic illusions that transform expectations, mark the form, and create meaning. I examine how he uses instrumental groupings to create distinct or blended auditory events, which I relate to musical structure. Using an aurally based analytical approach, I develop these descriptions of timbre and auditory scenes to interpret ways in which different timbre-spaces function. Through techniques such as timbral transformations, magical effects, and timbre and contour fusion, I examine the ways in which Ravel conjures sound objects in his music that are imaginary, transformative, or illusory. DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.1.0 Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory 1. Introduction [1.1] Throughout his career, Ravel’s sound often defied harmonic and formal expectations. While most analytic scholarship has treated Ravel’s use of timbre as secondary to the parameters of harmony and form, particularly in early- and middle-period compositions, recent scholarship has made timbre a central concern of Ravel’s style. -

Tzigane – Rhapsody for Violin and (Luthéal) Piano (1924)

Program Notes by Chris Darwin. Please use freely for non-commercial purposes. Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Tzigane – Rhapsody for violin and (Luthéal) piano (1924) The Luthéal piano was patented in 1919 by the prolific Belgian inventor George Cloetens, but it did not catch on. An elaborate mechanism was added to a normal grand piano which allowed three additional timbres to be produced independently for high and for low notes, under the control of organ-like stops: (i) a 'harpsichord-like' sound produced by a set of pins brought close enough to touch the vibrating string; (ii) a whispery timbre like a violin harmonic produced by a set of felts that could be lowered to touch each string halfway along its length; (iii) a sound like a Hungarian Cimbalom produced by both mechanisms used together. Ravel was clearly intrigued by the Luthéal's possibilities for gypsy music and specified it for Tzigane. He also wrote a part for itin his orchestral suite L'enfant et les sortilèges. The only surviving original example of the instrument, in Brussels' Musical Instrument Museum, has been renovated; their website (www.mim.be) has a recording of Tzigane being played using it. Tzigane was commissioned from Ravel by the virtuoso violinist Jelly d'Arányi, great-niece of Joseph Joachim. Ravel had been working on his violin sonata and she was due to give the first performance, but he was having trouble with it. So, writing a very different piece for her may have appealed to him. She gave the first performance of Tzigane in 1924 in London, with the Luthéal attachment added to the piano. -

Download This PDF File

JOURNAL OF RESEARCH ONLINE MusicA JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA ‘Jangling in symmetrical sounds’: Maurice Ravel as storyteller and poet aurice Ravel’s perception of language was defined by his métier. He thought EMILY KILPATRICK about words as a composer, understanding them in terms of their rhythms and Mresonances in the ear. He could recognise the swing of a perfectly balanced phrase, the slight changes of inflection that affect sense and emphasis, and the rhythm ■ Elder Conservatorium and melody inherent in spoken language. Ravel’s letters, his critical writings, his vocal of Music music and, most strikingly, his poetry, reveal his undeniable talent for literary expression. University of Adelaide He had a pronounced taste for onomatopoeia and seemed to delight in the dextrous South Australia 5005 juggling of rhymes and rhythms. As this paper explores, these qualities are particularly Australia apparent in the little song Noël des jouets (1905) and the choral Trois chansons pour chœur mixte sans accompagnement (1915) for which Ravel wrote his own texts, together Email: emily.kilpatrick with his collaboration with Colette on the opera L’Enfant et les sortilèges (1925). @adelaide.edu.au The common thread of fantasy and fairytale that runs through these three works suggests that through his expressive use of language Ravel was deliberately aligning his music with the traditions of storytelling, a genre defined by the sounds of the spoken word. Fairytales usually employ elegant and beautiful formal language that is direct, expressive and naturally musical, as typified in the memorable phrases‘Once upon a time…’ and ‘… happily ever after’. -

Classic Terms

Classic Terms Alberti Bass: "Broken" arpeggiated triads in a bass line, common in many types of Classic keyboard music; named after Domenico Alberti (1710-1740) who used it extensively but did not invent it. Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Bel Canto: (Italian for "beautiful singing") An Italian singing tradition primarily in opera seria and opera buffa in the late17th- to early-19th century. Characterized by seamless phrasing (legato), great breath control, flexibility, tone, and agility. Most often associated with singing done in the early-Romantic operas of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. Cadenza: An improvised or written-out ornamental virtuosic passage played by a soloist in a concerto. In Classic concertos, a cadenza occurs at a dramatic moment before the end of a movement, when the orchestra stops so the soloist can play in free time, and then after the cadenza is finished the orchestra reenters to bring the movement to its conclusion. Castrato The term for a male singer who was castrated before puberty to preserve his high soprano range (this practice in Italy lasted until the late 1800s). Today, the rendering of castrato roles is problematic because it requires either a male singing falsetto (weak) or a mezzo-soprano (strong, but woman must impersonate a man). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Empindsam: (German for "sensitive") The term used to describe a highly-expressive style of German pre- Classic/early Classic instrumental music, that was intended to intensely express true and natural feelings, featuring sudden contrasts of mood. -

Trois Chansons and World War I. (2014) Directed by Dr

JACKSON, AARON RONALD, D.M.A. Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons and World War I. (2014) Directed by Dr. Welborn E. Young. 62pp. Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) began writing Trois Chansons in November of 1914 and completed it in February of the following year. Durand Musical Editions published the composition in 1916. The Bathori-Engel Chorus, conducted by Louis Aubert, gave the premiere in October 1917. The compositional time frame coincides with Ravel’s numerous attempts to volunteer for military service at the onset of World War I (WWI) and his eventual enlistment in March of 1916. By all accounts, Trois Chansons is a unique addition to Ravel’s compositional oeuvre. Except for this work, Ravel wrote almost exclusively for instrumental genres; this composition is his only a cappella choral contribution. Additionally, the texts of each chanson are by the composer. The purpose of this document is to demonstrate that Trois Chansons represents a level of involvement in WWI through composition and contains Ravel’s both explicit and implicit commentary on WWI. This research encompasses general information about Chansons and commentary on Ravel’s attempts to enlist in the Armée de Terre. Also included are summaries of Ravel’s compositional components including text, genre, and personal dedications. Furthermore, this document outlines specific compositional devices utilized in Trois Chansons and includes representative musical analysis. Finally, through both compositional components and devices, this study suggests aspects of Ravel’s personal commentary on WWI. This document concludes with suggestions for further research on Trois Chansons. In addition to a compiled bibliography, appendices containing Ravel’s original poetry for Trois Chansons and conductor’s analysis pertaining to each chanson accompany the main body of research.