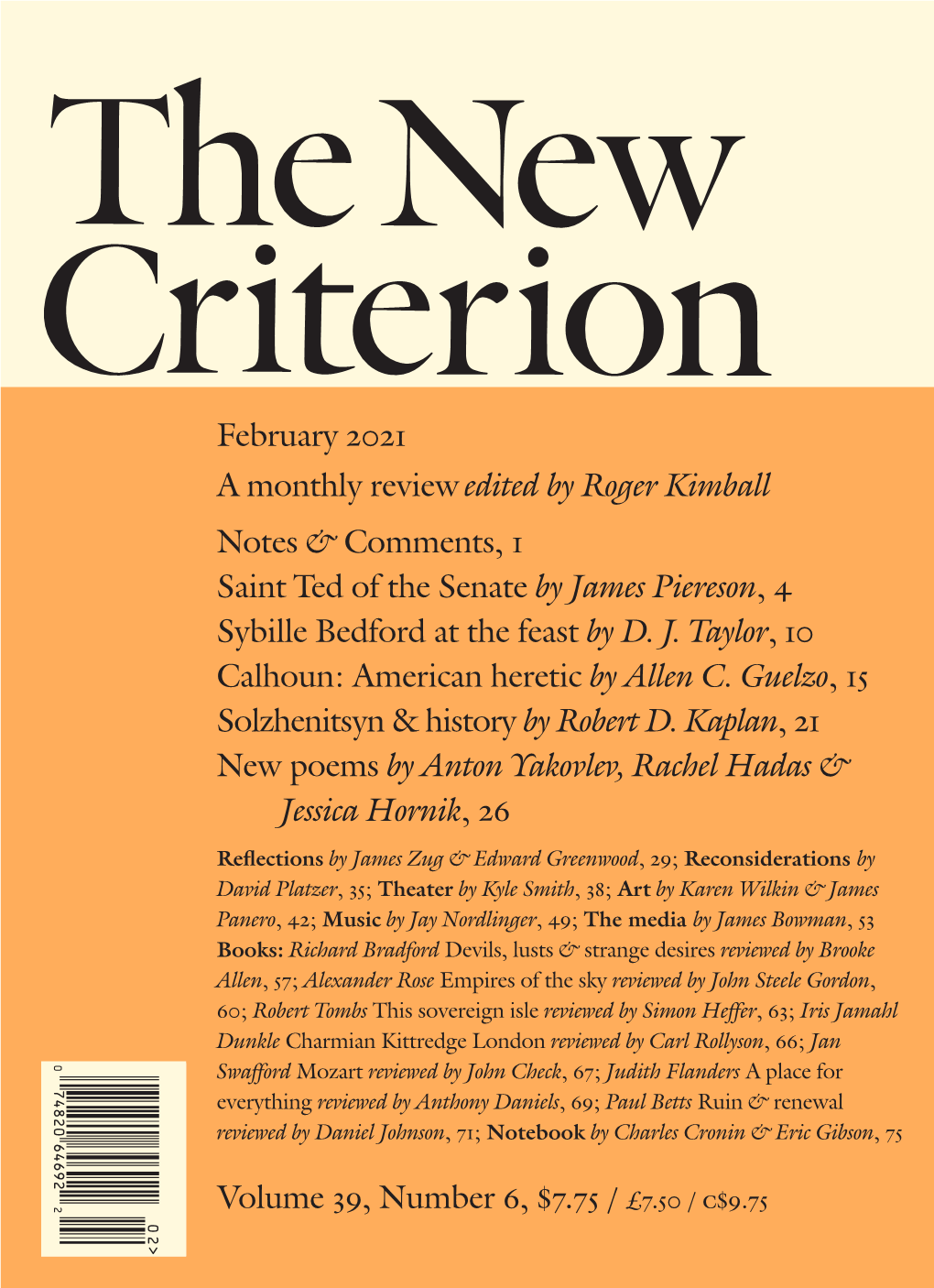

The New Criterion – February 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Liberty Actions Taken by Trump Administration 2017 on May

Religious Liberty Actions Taken By Trump Administration 2017 ● On May 4, 2017, President Trump signed an executive order that ensures religious organizations are protected from discrimination. ● In October 2017, the Trump administration announced that the U.S. will provide direct assistance to persecuted Christians in the Middle East. 2018 ● On January 2, 2018, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) announced changes in federal disaster funding that would include private non-profit houses of worship. ● In January 2018, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the formation of a Conscience and Religious Freedom Division within the HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR). The purpose of the division is to "restore federal enforcement of our nation's laws that protect the fundamental and unalienable right of conscience and religious freedom." ● In January 2018, the Justice Department designated a new section in the U.S. Attorney’s Manual specifically devoted to the protection of religious liberty. The section, entitled The "Associate Attorney General’s Approval and Notice Requirements for Issues Implicating Religious Liberty" will require all U.S. Attorney Offices to set up a point of contact for any civil suit involving religious freedom or liberty. ● In May 2018, President Trump signed an executive order to establish a White House Faith and Opportunity Initiative. The Initiative would "provide recommendations on the Administration’s policy agenda affecting faith based and community programs; provide recommendations on programs and policies where faith-based and community organizations may partner and/or deliver more effective solutions to poverty; apprise the Administration of any failures of the executive branch to comply with religious liberty protections under law; and reduce the burdens on the exercise of free religion." ● On July 30, 2018, U.S. -

Restored Republic Via a GCR As of Jan

Click here if you'd like to Donate to THE NEAL SHOW - THANKS !! Click here to see PAST SHOWS or get the Newsletter ~ Please share this with friends who may be interested ~ lkjlkjlj THE NEAL SHOW ~Community, Architecture and the Individual~ *** You can email me at [email protected] if you would like to be added to the list of subscribers to this newsletter. !! THE NEAL SHOW !! For the time being, I will be pre-recording shows and mounting them on the “PAST SHOWS” menu item you will see in the upper right hand corner of the "nealshow.com" website. I hope to have shows posted for you by Saturday between 1:00 and 4:00 PM. THIS IS THE TEMPORARY LINK TO ALL SHOWS FROM THIS DATE FORWARD. {{ http://www.nealshow.com/page/past_shows }} *** “My judgment is not delayed for I sit upon my throne each day and I bless and I punish, but the fullness of my wrath shall not come until the days when darkness declares itself victor and when my harvest of mercy has been a blessing unto the inhabitants of all the earth. In my hand is a cup and this means that my punishment has already been established and prepared and it will not be stayed and it will not pass. I will pour out my wrath upon the ones who seek darkness and walk therein and my wrath shall also be unto all who support the ways of 1 darkness and those who strive against light and truth. Look unto me and trust in me and understand that those who see the rainbow must also endure the storm.” ~David Nix *** Humility is the key to finding god. -

Quicksands: a Memoir PDF Book

QUICKSANDS: A MEMOIR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sybille Bedford | 384 pages | 15 May 2009 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140279764 | English | London, United Kingdom Quicksands: A Memoir PDF Book Trivia About Quicksands: A Memoir. To ask other readers questions about Quicksands , please sign up. Now that she's settled into the magnificence of her 90s, she has written a calm, exact, lovely book out of all that jangle of memories. Yet going over familiar ground for this book, the perspectives kept changing. Quicksands is beautifully beautifully written. This memoir is fascinating for the singular position of the narrator during the unparalleled turmoil of the early-mid C20th. Buy It Now. Her writing style is an acquired taste. In Sanary she fell in love - she dearly loves many men, but falls in love with women - and her mother, unhinged by her young husband's infidelity, became a morphine addict. Bedford's portrait of France's expat literary world in the buildup to WWII was the most interesting part of the book for me, but I found her discussion of her development as a writer quite interesting as well. Bedford was their child. Paula Fox, e. Quicksands: A Memoir by Sybille Bedford. Sybille was raised in the Roman Catholic faith of her father at Schloss Feldkirch in Baden, and had a half-sister, from her father's first marriage Maximiliane Henriette von Schoenebeck. Will try and find quote. She had a German passport and Jewish blood. My second hand book is a library book?????? When her young stepfather could take it no more, Bedford was left to handle the crooked doctors and the dockside dealers. -

Conservatism and Pragmatism in Law, Politics and Ethics

TOWARDS PRAGMATIC CONSERVATISM: A REVIEW OF SETH VANNATTA’S CONSERVATISM AND PRAGMATISM IN LAW, POLITICS, AND ETHICS Allen Mendenhall* At some point all writers come across a book they wish they had written. Several such books line my bookcases; the latest of which is Seth Vannatta’s Conservativism and Pragmatism in Law, Politics, and Ethics.1 The two words conservatism and pragmatism circulate widely and with apparent ease, as if their import were immediately clear and uncontroversial. But if you press strangers for concise definitions, you will likely find that the signification of these words differs from person to person.2 Maybe it’s not just that people are unwilling to update their understanding of conservatism and pragmatism—maybe it’s that they cling passionately to their understanding (or misunderstanding), fearing that their operative paradigms and working notions of 20th century history and philosophy will collapse if conservatism and pragmatism differ from some developed expectation or ingrained supposition. I began to immerse myself in pragmatism in graduate school when I discovered that its central tenets aligned rather cleanly with those of Edmund Burke, David Hume, F. A. Hayek, Michael Oakeshott, and Russell Kirk, men widely considered to be on the right end of the political spectrum even if their ideas diverge in key areas.3 In fact, I came to believe that pragmatism reconciled these thinkers, that whatever their marked intellectual differences, these men believed certain things that could be synthesized and organized in terms of pragmatism.4 I reached this conclusion from the same premise adopted by Vannatta: “Conservatism and pragmatism[] . -

2014 Catalogue

Daunt Books Publishing Spring & Summer 2014 Spring & Summer 2014 ince Daunt Books began publishing in 2010, we have Sbeen devoted to reissuing brilliant yet neglected books – the sort of titles we love to see on the shelves of our own bookshops. Over the past year we’ve also begun to discover and publish original works by talented authors from around the world. All of our books are inspired by the Daunt Books shops themselves, and the exciting atmos- phere of discovery to be found in a good bookshop. For our Spring & Summer season of 2014, we are pleased to be publishing two original titles. The first is a beguiling and hilarious debut novel – The Smoke is Rising by Mahesh Rao, set in the bustling Indian city of Mysore as it inches toward the future. Mahesh is one of the freshest new voices writing today. We are also delighted to be publishing Park Notes, a beautiful anthology exploring how London’s parks continue to inspire artists and writers, curated by award-winning painter Sarah Pickstone. And there are still plenty of classic reissues this season – including the darkly hilarious Nathanael West, a thriller set in revolutionary Iran by James Buchan, and a collec- tion of stunning travel writing from the inimitable Sybille Bedford. Happy reading! 4 5 The London Scene NOW AVAILABLE Virginia Woolf AVAILABLE NOW AVAILABLE Take a stroll through London with Virginia Woolf as your guide in this beautifully illustrated book. Introduced by Hermione Lee. From the docklands of the East End to the Houses of Parlia- ment; from the bustle of Oxford Street to peaceful moments on Hampstead Heath – Virginia Woolf explores the city’s hidden places and draws a remarkable portrait of the daily lives of £10.99 Londoners. -

DAILY FAVORITES from 2020: Note the Dates Are in Reverse Order with the Most Recent at the Top of the Page

DAILY FAVORITES from 2020: Note the dates are in reverse order with the most recent at the top of the page. [December 25-31, 2020] My Daily Favorites will restart on Jan 1, 2021. [December 24, 2020] The American Mind: 1. Professor John Eastman’s Response to the Latest Manifestation of Chapman Cancel Culture - https://americanmind.org/salvo/professor-john-eastmans-response-to-the-latest- manifestation-of-chapman-cancel-culture/ 2. In Defense of Stigma - https://americanmind.org/salvo/in-defense-of-stigma/ [December 23, 2020] Gatestone Institute: 1. Drug Trafficking: The Dirtiest Little Secret - https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/16874/mexico-border-drug-trafficking 2. The EU Needs to Stand Up for the Human Rights It Proclaims - https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/16871/eu-human-rights-china [December 22, 2020] Manhattan Contrarian: 1. Your Christmas Present: Our Political Leaders Are Killing Off New York City - https://www.manhattancontrarian.com/blog/2020-12-21-christmas-present-our-political- leaders-are-killing-off-new-york-city 2. Our Meaningless Measure of Poverty - https://www.manhattancontrarian.com/annals-of- poverty/ [December 21, 2020] George Shultz: 1. The 10 most important things I’ve learned about trust over my 100 years - https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/12/11/10-most-important-things-ive- learned-about-trust-over-my-100-years/ 2. George Shultz: A Century of Wisdom - https://www.hoover.org/research/george-shultz- century-wisdom [December 20, 2020] Gatestone Institute: 1. China: The Conquest of Hollywood - https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/16842/china- films-hollywood-censorship 2. To Europe with Love: "Diplomats" or Terrorists from Iran's Mullahs? - https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/16867/iran-diplomats-terrorists-europe [December 19, 2020] The American Prospect: 1. -

Commencement

COMMENCEMENT University of Wisconsin-Whitewater December 19, 2020 More than 150 years ago, on April 21, 1868, the state’s second normal school opened its doors to the first class of 48 students and nine faculty members. A progressive spirit guided the development of the institution as it evolved from a normal school, which trained teachers for one-room schools, to Whitewater State Teachers College (1927), Wisconsin State College-Whitewater (1951), Wisconsin State University-Whitewater (1964) and as a member of the 13 four-year institutions in the University of Wisconsin System (1971). Today, UW-Whitewater is a leading comprehensive university serving approximately 11,842 full- and part-time students with 50 undergraduate majors, 13 master’s degree programs, one doctoral degree and one education specialist degree in the colleges of Arts and Communication, Business and Economics, Education and Professional Studies, Integrated Studies, and Letters and Sciences. The university awards more than 2,700 degrees every year. Throughout its history, UW-Whitewater has produced graduates who have actively contributed to the growth of the state and nation. Student learning is the paramount focus of the university’s programs and services. The university takes pride in its regional leadership, national presence and global vision. Many of its academic programs are among the best in the country. 1 Student Speaker Brian Martinez For Brian Martinez, becoming a Warhawk meant finding a place to plant roots. When he visited campus as a transfer student from another Wisconsin university, UW-Whitewater felt like an inclusive family, where everyone belonged — a place that put people first. -

The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURN IN LATE 20TH CENTURY ART: A CASE STUDY OF HELEN AND NEWTON HARRISON AFTER MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN MODERN THOUGHT AND LITERATURE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LAURA CASSIDY ROGERS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Laura Cassidy Rogers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gy939rt6115 Includes supplemental files: 1. (Rogers_Circular Dendrogram.pdf) 2. (Rogers_Table_1_Primary.pdf) 3. (Rogers_Table_2_Projects.pdf) 4. (Rogers_Table_3_Places.pdf) 5. (Rogers_Table_4_People.pdf) 6. (Rogers_Table_5_Institutions.pdf) 7. (Rogers_Table_6_Media.pdf) 8. (Rogers_Table_7_Topics.pdf) 9. (Rogers_Table_8_ExhibitionsPerformances.pdf) 10. (Rogers_Table_9_Acquisitions.pdf) ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Zephyr Frank, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gail Wight I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ursula Heise Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. -

Bradley Impact Fund

FROM THE DESK OF GABE CONGER BY THE NUMBERS Dear Friends, This month, nearly 1.9 million students will graduate with a bachelor’s degree. What will they take away from their college experience? Many will earn a STEM degree or gain experience through internships. Leadership and technology skills will be enhanced. Yet, too few will have greater respect for vigorous public dialogue and diversity of viewpoints. The pressure to conform to the political correctness so pervasive on America’s college campuses is a barrier to young Americans learning and valuing the principles of free speech and freedom of thought. These principles CLASS1.9M OF 2019 were essential to the founding of our nation, and they are just as essential today. BACHELOR'S DEGREES With such extensive uniformity of opinion, the "informed citizenry" of today is not what our founding fathers pictured. Our theme for this issue is the intersection of the power of ideas, education, and informed citizens. Robert P. George, Princeton University professor and Bradley Foundation Board Member, shares his perspective as a conservative academic 10:1 engaged with young Americans at the threshold of their independence. We’re DEMOCRAT also pleased to announce the 2019 Bradley Prizes winners, whose work has PROFESSORS steadfastly advanced an informed citizenry. The Grant Recipient Spotlight will OUTNUMBER help you create your summer reading list; and in The Future is Now, we share REPUBLICAN Lincoln Network co-founder Aaron Ginn’s ideas for collaboration of like-minded technologists using their Silicon Valley skills to advance liberty and viewpoint diversity. Free thought and free speech are under fire in our society. -

The State of Art Criticism

Page 1 The State of Art Criticism Art criticism is spurned by universities, but widely produced and read. It is seldom theorized, and its history has hardly been investigated. The State of Art Criticism presents an international conversation among art historians and critics that considers the relation between criticism and art history, and poses the question of whether criticism may become a university subject. Participants include Dave Hickey, James Panero, Stephen Melville, Lynne Cook, Michael Newman, Whitney Davis, Irit Rogoff, Guy Brett, and Boris Groys. James Elkins is E.C. Chadbourne Chair in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His many books include Pictures and Tears, How to Use Your Eyes, and What Painting Is, all published by Routledge. Michael Newman teaches in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths College in the University of London. His publications include the books Richard Prince: Untitled (couple) and Jeff Wall, and he is co-editor with Jon Bird of Rewriting Conceptual Art. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 1 Page 2 The Art Seminar Volume 1 Art History versus Aesthetics Volume 2 Photography Theory Volume 3 Is Art History Global? Volume 4 The State of Art Criticism Volume 5 The Renaissance Volume 6 Landscape Theory Volume 7 Re-Enchantment Sponsored by the University College Cork, Ireland; the Burren College of Art, Ballyvaughan, Ireland; and the School of the Art Institute, Chicago. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 2 Page 3 The State of Art Criticism EDITED BY JAMES ELKINS AND MICHAEL NEWMAN 08:52:27:10:07 Page 3 Page 4 First published 2008 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. -

The Other Father in Barack Obama's Dreams from My Father

The Other Father in Barack Obama’s Dreams from my Father Robert Kyriakos Smith and King-Kok Cheung Much has been written about the father mentioned in the title of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father (1995), the Kenyan namesake who sired and soon abandoned the forty-fourth president of the United States. Also well noted is Stanley Ann Dunham, Obama’s White American mother who has her own biography, entitled A Singular Woman (2011). The collated material concerning this f eeting family of three lends itself to a simple math: Black father + White mother = Barack Obama; or, Africa + America = Barack Obama. But into these equations the present essay will introduce third terms: “ Asian stepfather” and “ Indonesia.” For if Barack Obama’s biography is to be in any way summed up, we must take into account both Lolo Soetoro (Obama’s Indonesian stepfather) and the nation of Lolo’s birth, a country where Obama spent a signif cant portion of his youth. Commentators’ neglect of Lolo, especially, is a missed literary-critical opportunity we take advantage of in the following essay. The fact that the title of Obama’s memoir explicitly references only one father may be seen to compound the oversight, especially since “my father” is a position that the absentee Barack Sr. for the most part, vacates. However, “my father” is also fundamentally a function that several people in Barack Jr.’s life perform. Therefore, in a sense, the Father of Obama’s title is always already multiple, pointing simultaneously to a biological father and to his surrogates. -

The Weekly Standard…Don’T Settle for Less

“THE ORACLE OF AMERICAN POLITICS” — Wolf Blitzer, CNN …don’t settle for less. POSITIONING STATEMENT The Weekly Standard…don’t settle for less. Through original reporting and prose known for its boldness and wit, The Weekly Standard and weeklystandard.com serve an audience of more than 3.2 million readers each month. First-rate writers compose timely articles and features on politics and elections, defense and foreign policy, domestic policy and the courts, books, art and culture. Readers whose primary common interests are the political developments of the day value the critical thinking, rigorous thought, challenging ideas and compelling solutions presented in The Weekly Standard print and online. …don’t settle for less. EDITORIAL: CONTENT PROFILE The Weekly Standard: an informed perspective on news and issues. 18% Defense and 24% Foreign Policy Books and Arts 30% Politics and 28% Elections Domestic Policy and the Courts The value to The Weekly Standard reader is the sum of the parts, the interesting mix of content, the variety of topics, type of writers and topics covered. There is such a breadth of content from topical pieces to cultural commentary. Bill Kristol, Editor …don’t settle for less. EDITORIAL: WRITERS Who writes matters: outstanding political writers with a compelling point of view. William Kristol, Editor Supreme Court and the White House for the Star before moving to the Baltimore Sun, where he was the national In 1995, together with Fred Barnes and political correspondent. From 1985 to 1995, he was John Podhoretz, William Kristol founded a senior editor and White House correspondent for The new magazine of politics and culture New Republic.