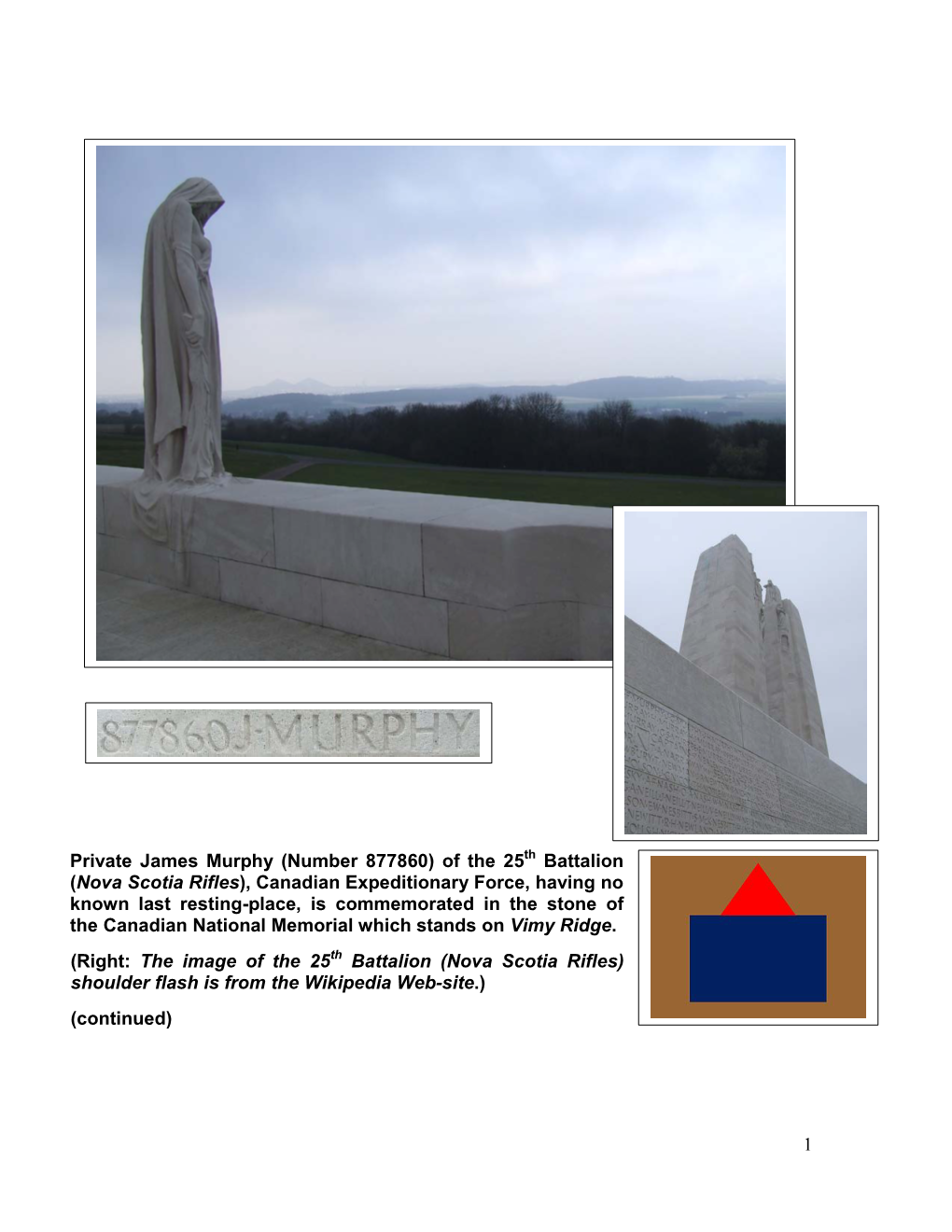

Murphy, James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholars Commons Canadian Military History Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 7 1-23-2012 Fifth aC nadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle William McAndrew Directorate of Heritage and History, Department of National Defence Recommended Citation McAndrew, William (1993) "Fifth aC nadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle," Canadian Military History: Vol. 2: Iss. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh/vol2/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McAndrew: Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle Bill McAndrew he Canadian government authorized the Equipping the division was a slow, drawn T formation of lst Canadian Armoured out process. By the end of July 1942, 5 CAB Division (CAD) early in 1941. It organized at had received only 40 per cent of its tanks, a Camp Borden in March and, redesignated 5th motley mixture of American General Lees and CAD, sailed for the United Kingdom in the fall. 1 Stuarts, along with a few Canadian-built Rams Originally its organization was based on two which were to be the formation's main battle armoured brigades (each of three regiments, a tank. Not for another year were sufficient motor battalion and a support group composed Rams available to fill the divisional of a field regiment, a Light Anti-Aircraft (LAA) establishment and, as a result, training regiment, an anti-tank regiment and an infantry suffered. -

Canadian Expeditionary Force – Formations Ledger (1970'S Typed

Canadian Expeditionary Force – Formations Ledger (1970’s typed ledger) Table Of Contents Index Table 1 1st Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 2nd Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 3rd Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 4th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 5th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 6th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 7th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 8th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 9th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 10th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 11th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 12th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 13th Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles Battalion 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles Battalion 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles Battalion 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles Battalion Canadian Mounted Rifles Depot Canadian Calvary Depot Canadian Cavalry Training Brigade - Reserve Cavalry Regiment Canadian Cavalry Troops – Royal Canadian Dragoons Depot, Toronto Lord Strathcona Horse (Royal Canadians) Depot, Winnipeg Fort Garry Horse Depot, Winnipeg Canadian Corps Cyclists Battalion 1st Canadian Division Cyclist Company 2nd Canadian Division Cyclist Company 3rd Canadian Division Cyclist Company 4th Canadian Division Cyclist Company Canadian Reserve Cyclist Company No. 1 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 2 Cyclist Depot Platoon Table 2 No. 3 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 4 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 5 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 6 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 10 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 11 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 12 Cyclist Depot Platoon No. 13 Cyclist Depot Platoon 19th Alberta Dragoons Overseas Draft 5th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards Overseas Draft 30th Regiment (British Columbia Horse) Overseas Draft Page 1 of 61 Canadian Expeditionary Force – Formations Ledger (1970’s typed ledger) Table Of Contents Index 31st Regiment (British Columbia Horse) Overseas Draft 15th Light Horse Overseas Draft 16th Light Horse Overseas Draft 1st Hussars Overseas Draft 35th Central Alberta Horse Overseas Draft Cyclist Depot, Military District No. -

Canadian Army Morale, Discipline and Surveillance in the Second World War, 1939-1945

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-09-29 Medicine and Obedience: Canadian Army Morale, Discipline and Surveillance in the Second World War, 1939-1945. Pratt, William Pratt, W. (2015). Medicine and Obedience: Canadian Army Morale, Discipline and Surveillance in the Second World War, 1939-1945. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26871 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2540 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Medicine and Obedience: Canadian Army Morale, Discipline, and Surveillance in the Second World War, 1939-1945. by William John Pratt A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2015 © William John Pratt 2015 Abstract In the Second World War Canadian Army, medicine and discipline were inherently linked in a system of morale surveillance. The Army used a wide range of tools to monitor morale on medical lines. A basic function of Canadian medical officers was to keep units and formations up to strength, not only by attending to their basic health, but also by scrutinizing ailments under suspicion of malingering. -

Waterloo County Soldier Information Cards - World War II

Waterloo County Soldier Information Cards - World War II Residence [R] or Last Name First Name Rank Regiment/Battalion Hometown [H] A H.Q. Company, Highland Light Infantry of Ableson Albert Private Canada Galt [H] Ableson Gordon L. Stoker First Class Royal Canadian Navy Galt [H] Adam Kenneth F. Pilot Officer Royal Canadian Air Force Elmira [H], Preston [R] Adamos John Private Essex Scottish Regiment Kitchener Adams G. n/a Veterans Guard of Canada Galt [R] Adams Hector J. Gunner Royal Canadian Artillery Preston Adams Hugh B. Trooper Royal Canadian Armoured Corps Norwood [H] Adams William C. n/a Highland Light Infantry of Canada Preston [H] Adams Lawrence R. Private Quebec Royal Rifles Kitchener Addis Harold Private Western Ontario Regiment Preston [H] Agnew Archie Sergeant Hastings and Price Edward Regiment Galt [R] Aigner Frank Lance Corporal Highland Light Infantry of Canada Waterloo Airdrie Douglas Private n/a Elora Aitchinson Edward Flight Lieutenant Royal Canadian Air Force Elora Aitken George M. Private Irish Regiment of Canada Galt [H] Aitken W.T. "Bill" Second Lieutenant "C" Company, Highland Light Infantry of Canada Galt South Dumfries Township Aitkin George Captain Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury Regiment [H] Aksim R.E. Captain Intelligence Corps Waterloo [R] Aksim Victor Captain Royal Canadian Corps of Signals Waterloo Albert Leo N. Private Highland Light Infantry of Canada Preston [H], Kitchener [R] Albrecht George Private Essex Scottish Regiment Milverton Alderman Frederick Corporal Highland Light Infantry of Canada Galt [R] Aldworth G. Louis Pilot Officer Royal Canadian Air Force n/a Alexander Clem Lance Corporal "D" Company, Highland Light Infantry of Canada Galt [R] Alexander Jack Paratrooper Paratroop Units Hespeler Alexander James Private Royal Canadian Infantry Corps Hespeler Alexander Thomas W. -

Title: the Canadian Army Battle Drill School at Rowlands Castle 1942

Title: The Canadian Army Battle Drill School at Rowlands Castle 1942 Author: Brian Tomkinson Date: January 2017 Summary: This report has been inspired by the “Secrets of the High Woods” Project, funded by the South Downs national Park and the National Lottery. The object of this report is to link features identified by the LIDAR survey with military activities in the Rowlands Castle/Stansted Park area and specifically to tell the story of the Canadian Army Training School while it was located in Rowlands Castle. Apart from being of interest to local residents it is also hoped that the report will assist people engaged in family history research. This article is published with the kind permission of the author. This article is the work and views of the author from research undertaken in the Record Offices by volunteers of the Secrets of the High Woods project. South Downs National Park Authority is very grateful to the volunteers for their work but these are not necessarily the views of the Authority. 1 The Canadian Army Battle Drill School at Rowlands Castle – 1942 Foreword This report has been inspired by the “Secrets of the High Woods” Project, funded by the South Downs national Park and the National Lottery. The project is based on an airborne LiDAR survey covering an area of the South Downs National Park roughly between the A3 road in the west and the river Arun in the east. The survey was carried out to reveal archaeological ground features currently hidden and protected by existing woodland. A Key element of the project was volunteer community involvement. -

Holland Brochure - English Final with Bleed 032905.Indd 1 29/03/2005 3:04:15 PM When Field Marshal Montgomery Declared, “We

The Canadians and the Liberation of the Netherlands April-May 1945 Holten Canadian War Cemetery from the air. The Canadian Battlefi elds Foundation Holland brochure - english final with bleed 032905.indd 1 29/03/2005 3:04:15 PM When Field Marshal Montgomery declared, “we have won the battle of the Rhine,” on 28 March 1945 Northern Holland Emden it was fi nally possible to begin the liberation of those 23 March to 22 April 1945 Delfzijl provinces of the Netherlands still under Nazi occupation. Leer Groningen Montgomery gave this task to First Canadian Army Leeuwarden which was to open a supply route through Arnhem before clearing “Northeast” and “West Holland.” Within Ems nd 3rd Cdn Inf Div the Canadian Army 2 Canadian Corps was responsible Küsten Canal for Northeast Holland while 1st Canadian Corps, just arrived from Italy, was to advance to the west. Britain’s 49th (West Riding) Division, which had been preparing for the river crossing at Arnhem, continued to serve with 2nd Cdn Inf Div First Canadian Army throughout April and May. Meppen If the story of Canadian operations in April 1st Pol Armd Div contains no great decisive battles, it includes a potent Ijssel mix of both triumph and tragedy. Canadian and Dutch Zwolle Ijsselmeer memories of April are usually recollections of that “sweetest of springs,” the spring of liberation. Canadian Ems Almelo soldiers found themselves engulfed by a joyous Holten population which knew, all too well, what the war had Deventer Apeldoorn Canal been fought for, and they showered their liberators with Apeldoorn Twente Canal kisses and fl owers and love. -

Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle

Canadian Military History Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 7 1993 Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle William McAndrew Directorate of Heritage and History, Department of National Defence Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation McAndrew, William "Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle." Canadian Military History 2, 2 (1993) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McAndrew: Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle Fifth Canadian Armoured Division: Introduction to Battle Bill McAndrew he Canadian government authorized the Equipping the division was a slow, drawn T formation of lst Canadian Armoured out process. By the end of July 1942, 5 CAB Division (CAD) early in 1941. It organized at had received only 40 per cent of its tanks, a Camp Borden in March and, redesignated 5th motley mixture of American General Lees and CAD, sailed for the United Kingdom in the fall. 1 Stuarts, along with a few Canadian-built Rams Originally its organization was based on two which were to be the formation's main battle armoured brigades (each of three regiments, a tank. Not for another year were sufficient motor battalion and a support group composed Rams available to fill the divisional of a field regiment, a Light Anti-Aircraft (LAA) establishment and, as a result, training regiment, an anti-tank regiment and an infantry suffered. -

Soldiers Without Photo Nova Scotia Buried at the Canadian War Cemetery in Holten, the Netherlands

Soldiers Without Photo Nova Scotia Buried at the Canadian War Cemetery in Holten, The Netherlands Date of Surname First Rank Service # Regiment Death Age Birthplace Province Armstrong Howard W. Tpr F/30344 The Fort Garry Horse - 10th Armd. Regiment 5-Sep-45 25 Lunenburg Co. Nova Scotia Brown William E. Gdsm F/79788 The Canadian Grenadier Guards - 22nd Armd. Regt.23-Apr-45 28 Upper MusquodoboitNova Scotia Colford Lorne M. Pte F/9639 The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry 14-Apr-45 22 Dartmouth Nova Scotia Farrow Douglas B. Cpl F/49848 The Algonquin Regt. 26-Apr-45 27 Armherst Nova Scotia Fougere Joseph G. Pte F/79904 The Perth Regiment 26-Apr-45 28 Poulamon Nova Scotia Hamilton Merle V. Tpr F/56567 12th Manitoba Dragoons - 18th Armd. Car Regt.19-Apr-45 26 Brookfield Nova Scotia Harvey Robert C. Tpr F/86035 The British Columbia Regt. - 28th Armd. Regt. 22-Apr-45 23 Centre Burlington Nova Scotia Johnson Gordon F. Sgt F/49854 The North Nova Scotia Highlanders 8-Apr-45 33 Truro Nova Scotia Jury Douglas Spr F/77424 Royal Canadian Engineers - 18 Field Coy. 17-Aug-45 26 Joggins Mines Nova Scotia Lucas Lawrence E.Pte F/37218 The Algonquin Regt. 23-Apr-45 19 Guysburough Nova Scotia MacKenzie Donald C. Lt MC The Royal Winnipeg Rifles 22-Apr-45 30 Springhill Nova Scotia MacLean Neil R. Pte F/35471 The Carleton and York Regiment 12-May-45 27 Lourdes Nova Scotia MacLeod Joseph T. Sgt F/45568 The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry 13-Apr-45 30 Barney's River Nova Scotia Matheson William H. -

5Th CANADIAN DIVISION

5th CANADIAN DIVISION A proposal from Sir Sam Hughes for the formation of 5th and 6th Canadian Divisions from infantry battalions in England was made as early as the summer of 1916. By autumn of that year a number of infantry battalions had been selected for inclusion but no further action was taken until October 27th when the Chief of the Imperial General Staff asked if it would be possible to mobilize a 5th Division. (The idea of a 6th Division was dropped at this time.) However the requirements for reinforcing a 5th Division saw Canadian authorities demure and after a further request was made on January 1st 1917 a conference was held January 12th in which it was decided that a 5th Division would be raised in England but not proceed to France. The Division was formed February 13th 1917 at Witley under command of Major-General Garnet B. Hughes, who was promoted from command of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade on the Continent. On February 9th 1918 eleven of the remaining infantry battalions, the 199th battalion previously having been depleted for reinforcements., were ordered to provide an additional 100 men to each of the battalions serving on the Western Front and the 5th Division was disbanded. The field artillery and machine gun batteries however did proceed to France. No regimental numbers block numbers are listed for either Divisional or Brigade Headquarters of the 5th Division the personnel being drawn from troops already overseas. The 5th Canadian Division concentrated at Witley in Surry in February 1917 with the following infantry Brigades the 13th, 14th 15th, Lines of Communications troops, three Brigade Machine Gun Companies and the 5th Divisional Artillery. -

Canadian Army, 3 September 1939

Canadian Army 3 September 1939 Military District 1: HQ London, Ontario (SW Ontario-Canadian Service Numbers - MD 1 A) A. Permanent Force RHQ, C Company, The Royal Canadian Regiment: London No. 1 Detachment, The Royal Canadian Engineers: London No. 1 Detachment, The Royal Canadian Corps of Signals: London B. Non-Permanent Active Militia 1st Infantry Brigade: HQ London The Elgin Regiment: St. Thomas D Company: Aylmer The Essex Scottish: Windsor The Middlesex and Huron Regiment: Strathroy B Company: London C Company: Goderich D Company: Seaforth The Kent Regiment M-G: Chatham The Canadian Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) Machine Gun: London (Attached) The Essex Regiment (Tank): Windsor (Attached) 2nd Infantry Brigade: HQ Kitchener The Highland Light Infantry of Canada: Galt D Company: Preston The Oxford Rifles: Woodstock D Company: Ingersoll The Scots Fusiliers of Canada: Kitchener The Perth Regiment M-G: Stratford D Company: St. Mary's 1st Hussars: London 7th Field Brigade, RCA: London 12th (London), 55th Batteries: London 26th (Lambton) Battery: Sarnia 48th Battery (Howitzer): Watford 11th Field Brigade RCA: Guelph 16th, 29th (How), 43rd, 63rd Batteries: Guelph 21st Field Brigade, RCA: Listowel 97th (Bruce) Battery (How): Walkerton 98th (Bruce) Battery: Port Elgin 99th Battery: Wingham 100th Battery: Listowel HQ District Engineers 1: London 7th Field Company, RCE: London 11th (Lambton) Fie1d Company, RCE: Sarnia 1st (Lambton) Field Park Company, RCE: Sarnia 1 1st Army Troops Company, RCE: London No. 1 District Signals: London No. 1 Tank Battalion Signal Section: Windsor University of Western Ontario Contingent, Canadian 0fficers Training Corps: London Ontario Agricultural College Contingent, COTC: London Military District 2: HQ Toronto, Ontario (Central Ontario-Canadian Service Numbers - MD 2 B) A. -

A Cape Bretoner at War: Letters from the Front 1914-1919

Canadian Military History Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 4 2002 A Cape Bretoner at War: Letters from the Front 1914-1919 Brian Tennyson Cape Breton University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Recommended Citation Tennyson, Brian "A Cape Bretoner at War: Letters from the Front 1914-1919." Canadian Military History 11, 1 (2002) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tennyson: A Cape Bretoner at War A Cape Bretoner At War Letters From the Front 1914-1919 Brian Douglas Tennyson Introduction England, emigrated to Canada, and settled on the island, albeit at an early age. This fact, he production of books, journal and however, made him very typical of many Cape Tmagazine articles and films on the First Bretoners, particularly those living in the Sydney World War has become a veritable industry in area at the time of the war. Until the end of the recent years, reflecting society's belated nineteenth century, the Sydney area, like much realization that it marked a profoundly of Maritime Canada, was essentially a rural important milestone if not turning point in the community which earned its livelihood from history of the modern world. Prominent among farming, fishing, shipbuilding and the carrying the books that began to appear as early as the trade. What distinguished it from other areas 1920s and are still being published today are was the presence of vast coal deposits which had the memoirs, diaries and letters of men who been worked since the middle of the eighteenth served in the war.