Practica[ Less~Rbs :C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

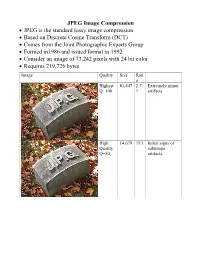

JPEG Image Compression

JPEG Image Compression JPEG is the standard lossy image compression Based on Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) Comes from the Joint Photographic Experts Group Formed in1986 and issued format in 1992 Consider an image of 73,242 pixels with 24 bit color Requires 219,726 bytes Image Quality Size Rati o Highest 81,447 2.7: Extremely minor Q=100 1 artifacts High 14,679 15:1 Initial signs of Quality subimage Q=50 artifacts Medium 9,407 23:1 Stronger Q artifacts; loss of high frequency information Low 4,787 46:1 Severe high frequency loss leads to obvious artifacts on subimage boundaries ("macroblocking ") Lowest 1,523 144: Extreme loss of 1 color and detail; the leaves are nearly unrecognizable JPEG How it works Begin with a color translation RGB goes to Y′CBCR Luma and two Chroma colors Y is brightness CB is B-Y CR is R-Y Downsample or Chroma Subsampling Chroma data resolutions reduced by 2 or 3 Eye is less sensitive to fine color details than to brightness Block splitting Each channel broken into 8x8 blocks no subsampling Or 16x8 most common at medium compression Or 16x16 Must fill in remaining areas of incomplete blocks This gives the values DCT - centering Center the data about 0 Range is now -128 to 127 Middle is zero Discrete cosine transform formula Apply as 2D DCT using the formula Creates a new matrix Top left (largest) is the DC coefficient constant component Gives basic hue for the block Remaining 63 are AC coefficients Discrete cosine transform The DCT transforms an 8×8 block of input values to a linear combination of these 64 patterns. -

COLOR SPACE MODELS for VIDEO and CHROMA SUBSAMPLING

COLOR SPACE MODELS for VIDEO and CHROMA SUBSAMPLING Color space A color model is an abstract mathematical model describing the way colors can be represented as tuples of numbers, typically as three or four values or color components (e.g. RGB and CMYK are color models). However, a color model with no associated mapping function to an absolute color space is a more or less arbitrary color system with little connection to the requirements of any given application. Adding a certain mapping function between the color model and a certain reference color space results in a definite "footprint" within the reference color space. This "footprint" is known as a gamut, and, in combination with the color model, defines a new color space. For example, Adobe RGB and sRGB are two different absolute color spaces, both based on the RGB model. In the most generic sense of the definition above, color spaces can be defined without the use of a color model. These spaces, such as Pantone, are in effect a given set of names or numbers which are defined by the existence of a corresponding set of physical color swatches. This article focuses on the mathematical model concept. Understanding the concept Most people have heard that a wide range of colors can be created by the primary colors red, blue, and yellow, if working with paints. Those colors then define a color space. We can specify the amount of red color as the X axis, the amount of blue as the Y axis, and the amount of yellow as the Z axis, giving us a three-dimensional space, wherein every possible color has a unique position. -

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

The Video Codecs Behind Modern Remote Display Protocols Rody Kossen

The video codecs behind modern remote display protocols Rody Kossen 1 Rody Kossen - Consultant [email protected] @r_kossen rody-kossen-186b4b40 www.rodykossen.com 2 Agenda The basics H264 – The magician Other codecs Hardware support (NVIDIA) The basics 4 Let’s start with some terms YCbCr RGB Bit Depth YUV 5 Colors 6 7 8 9 Visible colors 10 Color Bit-Depth = Amount of different colors Used in 2 ways: > The number of bits used to indicate the color of a single pixel, for example 24 bit > Number of bits used for each color component of a single pixel (Red Green Blue), for example 8 bit Can be combined with Alpha, which describes transparency Most commonly used: > High Color – 16 bit = 5 bits per color + 1 unused bit = 32.768 colors = 2^15 > True Color – 24 bit Color + 8 bit Alpha = 8 bits per color = 16.777.216 colors > Deep color – 30 bit Color + 10 bit Alpha = 10 bits per color = 1.073 billion colors 11 Color Bit-Depth 12 Color Gamut Describes the subset of colors which can be displayed in relation to the human eye Standardized gamut: > Rec.709 (Blu-ray) > Rec.2020 (Ultra HD Blu-ray) > Adobe RGB > sRBG 13 Compression Lossy > Irreversible compression > Used to reduce data size > Examples: MP3, JPEG, MPEG-4 Lossless > Reversable compression > Examples: ZIP, PNG, FLAC or Dolby TrueHD Visually Lossless > Irreversible compression > Difference can’t be seen by the Human Eye 14 YCbCr Encoding RGB uses Red Green Blue values to describe a color YCbCr is a different way of storing color: > Y = Luma or Brightness of the Color > Cr = Chroma difference -

Wwf Raw May 18 1998

Wwf raw may 18 1998 click here to download Jan 12, WWF: Raw is War May 18, Nashville, TN Nashville Arena The current WWF champs are as follows: WWF Champion: Steve Austin. Apr 22, -A video package recaps how Vince McMahon has stacked the deck against WWF Champion Steve Austin at Over the Edge and the end of last. Monday Night RAW Promotion WWF Date May 18, Venue Nashville Arena City Nashville, Tennessee Previous episode May 11, Next episode May. Apr 9, WWF Monday Night RAW 5/18/ Hot off the heels of some damn good shows I feel that it will continue. Nitro is preempted again and RAW. May 19, Craig Wilson & Jamie Lithgow 'Monday Night Wars' continues with the episodes of Raw and Nitro from 18 May Nitro is just an hour long. May 21, Monday Night Raw: May 18th, Last week, Dude Love was reinvented as a suit-wearing suit (nice one, eh?) and named the number one. Monday Night Raw May 18 Val Venis vs. 2 Cold Scorpio Terry Funk vs. Marc Mero Disciples of Apocalypse vs. LOD Dude Love vs. Dustin Runnells. Jan 5, May 18, – RAW: Val Venis b Too Cold Scorpio, Terry Funk b Marc Mero, The Disciples of Apocalypse b LOD (Hawk & Animal), Dude. Dec 22, Publicly, Vince has ignored the challenge, but WWF as a whole didn't. On Raw, Jim Ross talked shit about WCW for the whole show. X-Pac and. On the April 13, episode of Raw Is War, Dude Love interfered in a WWF World On the May 18 episode of Raw Is War, Vader attacked Kane during a tag . -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Image Compression GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) LZW (Lempel

GIF (Graphics Interchange Image Compression Format) • GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) • Introduced by Compuserve in 1987 (GIF87a), multiple-image in one file/application specific • PNG (Portable Network Graphics)/MNG metadata support added in 1989 (GIF89a) (Multiple-image Network Graphics) • LZW (Lempel-Ziv-Welch) compression replaced • JPEG (Joint Pictures Experts Group) earlier RLE (Run Length Encoding) B&W version – Patented by Compuserve/Unisys (has run out in US, will run out in June 2004 in Europe) • Maximum of 256 colours (from a palette) including a “transparent” colour • Optional interlacing feature • http://www.w3.org/Graphics/GIF/spec-gif89a.txt LZW (Lempel-Ziv-Welch) LZW Algorithm • Most of this method was invented and published • Dictionary initially contains all possible one byte codes by Lempel and Ziv in 1978 (LZ78 algorithm) (256 entries) • Input is taken one byte at a time to find the longest initial • A few details and improvements were later given string present in the dictionary by Welch in 1984 (variable increasing index sizes, • The code for that string is output, then the string is efficient dictionary data structure) extended with one more input byte, b • Achieves approx. 50% compression on large • A new entry is added to the table mapping the extended English texts string to the next unused code • superseded by DEFLATE and Burrows-Wheeler • The process repeats, starting from byte b transform methods • The number of bits in an output code, and hence the maximum number of entries in the table is fixed • once -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Edge of Life by Joe Hart Martha Hart on Vince Mcmahon Not Stopping "Over the Edge" PPV Following Owen’S Death

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Edge of Life by Joe Hart Martha Hart On Vince McMahon Not Stopping "Over The Edge" PPV Following Owen’s Death. Martha Hart recently spoke with CBS Sports to promote Tuesday’s “Dark Side of the Ring” episode on the death of her husband, former WWE Superstar Owen Hart. Owen passed away on May 23, 1999 at the WWE Over The Edge pay-per-view after a stunt for his entrance went wrong. Martha holds WWE directly responsible for Owen falling almost 80 feet to his death and says WWE took cost-cutting shortcuts on performing the stunt, hiring unqualified personnel and setting off a domino effect of catastrophic choices. Martha named Bobby Talbert as the “hacker” hired after experienced rigger Joe Branam had refused to do the stunt. Branam had done rigging work for The Rolling Stones and Elton John, among others. “First of all, the stunt itself was so negligent,” Hart said. “They hired hackers they knew would do anything they wanted when they knew that proper riggers they had hired in the past had told them, ‘We won’t do this kind of stunt, it’s not safe.’ Everything about that stunt was done wrong. The entire set-up was wrong. The equipment was wrong — the harness, for example, was meant for dragging people behind a car. It was a stunt harness, but it wasn’t meant to suspend someone 80 feet above the ground. “What was happening to Owen when he was sitting in that harness is, his circulation was getting cut off and he couldn’t breathe. -

Basics of Video

Analog and Digital Video Basics Nimrod Peleg Update: May. 2006 1 Video Compression: list of topics • Analog and Digital Video Concepts • Block-Based Motion Estimation • Resolution Conversion • H.261: A Standard for VideoConferencing • MPEG-1: A Standard for CD-ROM Based App. • MPEG-2 and HDTV: All Digital TV • H.263: A Standard for VideoPhone • MPEG-4: Content-Based Description 2 1 Analog Video Signal: Raster Scan 3 Odd and Even Scan Lines 4 2 Analog Video Signal: Image line 5 Analog Video Standards • All video standards are in • Almost any color can be reproduced by mixing the 3 additive primaries: R (red) , G (green) , B (blue) • 3 main different representations: – Composite – Component or S-Video (Y/C) 6 3 Composite Video 7 Component Analog Video • Each primary is considered as a separate monochromatic video signal • Basic presentation: R G B • Other RGB based: – YIQ – YCrCb – YUV – HSI To Color Spaces Demo 8 4 Composite Video Signal Encoding the Chrominance over Luminance into one signal (saving bandwidth): – NTSC (National TV System Committee) North America, Japan – PAL (Phased Alternation Line) Europe (Including Israel) – SECAM (Systeme Electronique Color Avec Memoire) France, Russia and more 9 Analog Standards Comparison NTSC PAL/SECAM Defined 1952 1960 Scan Lines/Field 525/262.5 625/312.5 Active horiz. lines 480 576 Subcarrier Freq. 3.58MHz 4.43MHz Interlacing 2:1 2:1 Aspect ratio 4:3 4:3 Horiz. Resol.(pel/line) 720 720 Frames/Sec 29.97 25 Component Color TUV YCbCr 10 5 Analog Video Equipment • Cameras – Vidicon, Film, CCD) • Video Tapes (magnetic): – Betacam, VHS, SVHS, U-matic, 8mm ... -

Chroma Subsampling Influence on the Perceived Video Quality for Compressed Sequences in High Resolutions

DIGITAL IMAGE PROCESSING AND COMPUTER GRAPHICS VOLUME: 15 j NUMBER: 4 j 2017 j SPECIAL ISSUE Chroma Subsampling Influence on the Perceived Video Quality for Compressed Sequences in High Resolutions Miroslav UHRINA, Juraj BIENIK, Tomas MIZDOS Department of Multimedia and Information-Communication Technologies, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Zilina, Univerzitna 1, 01026, Zilina, Slovak Republic [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] DOI: 10.15598/aeee.v15i4.2414 Abstract. This paper deals with the influence of 2. State of the Art chroma subsampling on perceived video quality mea- sured by subjective metrics. The evaluation was Although many research activities focus on objective done for two most used video codecs H.264/AVC and and subjective video quality assessment, only a few of H.265/HEVC. Eight types of video sequences with Full them analyze the quality affected by chroma subsam- HD and Ultra HD resolutions depending on content pling. In the paper [1], the efficiency of the chroma were tested. The experimental results showed that ob- subsampling for sequences with HDR content using servers did not see the difference between unsubsampled only objective metrics is assessed. The paper [2] and subsampled sequences, so using subsampled videos presents a novel chroma subsampling strategy for com- is preferable even 50 % of the amount of data can be pressing mosaic videos with arbitrary RGB-CFA struc- saved. Also, the minimum bitrates to achieve the good tures in H.264/AVC and High Efficiency Video Coding and fair quality by each codec and resolution were de- (HEVC). -

View Study (E19007) Luc Goethals, Nathalie Barth, Jessica Guyot, David Hupin, Thomas Celarier, Bienvenu Bongue

JMIR Aging Volume 3 (2020), Issue 1 ISSN: 2561-7605 Editor in Chief: Jing Wang, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN Contents Editorial Mitigating the Effects of a Pandemic: Facilitating Improved Nursing Home Care Delivery Through Technology (e20110) Linda Edelman, Eleanor McConnell, Susan Kennerly, Jenny Alderden, Susan Horn, Tracey Yap. 3 Short Paper Impact of Home Quarantine on Physical Activity Among Older Adults Living at Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Interview Study (e19007) Luc Goethals, Nathalie Barth, Jessica Guyot, David Hupin, Thomas Celarier, Bienvenu Bongue. 10 Original Papers Impact of the AGE-ON Tablet Training Program on Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Attitudes Toward Technology in Older Adults: Single-Group Pre-Post Study (e18398) Sarah Neil-Sztramko, Giulia Coletta, Maureen Dobbins, Sharon Marr. 15 Clinician Perspectives on the Design and Application of Wearable Cardiac Technologies for Older Adults: Qualitative Study (e17299) Caleb Ferguson, Sally Inglis, Paul Breen, Gaetano Gargiulo, Victoria Byiers, Peter Macdonald, Louise Hickman. 23 Actual Use of Multiple Health Monitors Among Older Adults With Diabetes: Pilot Study (e15995) Yaguang Zheng, Katie Weinger, Jordan Greenberg, Lora Burke, Susan Sereika, Nicole Patience, Matt Gregas, Zhuoxin Li, Chenfang Qi, Joy Yamasaki, Medha Munshi. 31 The Feasibility and Utility of a Personal Health Record for Persons With Dementia and Their Family Caregivers for Web-Based Care Coordination: Mixed Methods Study (e17769) Colleen Peterson, Jude Mikal, Hayley McCarron, Jessica Finlay, Lauren Mitchell, Joseph Gaugler. 40 Perspectives From Municipality Officials on the Adoption, Dissemination, and Implementation of Electronic Health Interventions to Support Caregivers of People With Dementia: Inductive Thematic Analysis (e17255) Hannah Christie, Mignon Schichel, Huibert Tange, Marja Veenstra, Frans Verhey, Marjolein de Vugt. -

Digital Video Video

Digital Video Video Video come from a camera, which records what it sees as a sequence of image Image frames comprise the video – Frame rate = presentation of successive frames – Minimal image changing between frames – Frequency of frames is measured in frames per second (fps) Sequence of still images creates the illusion of movement – > 16 fps is “smooth” – Standards: 29.97 fps NTSC 24 fps for movies 25 fps for PAL 60 fps for HDTV Digital Video Formats Most video signals are color signals, YCbCr, RGB, etc. The YCbCr color representation is used for most video coding standards compliance with the CCIR601, CIF, SIF formats CCIR601: International Radio Consultation Committee) – Three components, Y Cb Cr – CCIR format has two option: • One for the NTSC TV system – 525 lines/frame @30 fps – Y= 720x480 active pixels – Cb, Cr = 360x240 active pixels, (4:2:2) • Another one for the PAL system – 625 lines/fram @25 fps – Y = 720x576 active pixels – Cb, Cr = 360x288 active pixels, (4:2:0) – SIF: Source Input Format • Y = 360x240 pixel/frame @ 30 fps; Y = 360x288 pixel/frame @25 fps • Cb, Cr = y/2 = 180x120 pixel/frame – CIF: Common Intermediate Format Note on Digital Video Sup-sampling The human eye responds more precisely to brightness information than it does to color, chroma subsampling ( decimating) takes advantage of this. o In a 4:4:4 scheme, each 8×8 matrix of RGB pixels converts to three YCrCb 8×8 matrices: one for luminance (Y) and one for each of the two chrominance bands (Cr and Cb). o A 4:2:2 scheme also creates one 8×8 luminance matrix but decimates every two horizontal pixels to create each chrominance-matrix entry.