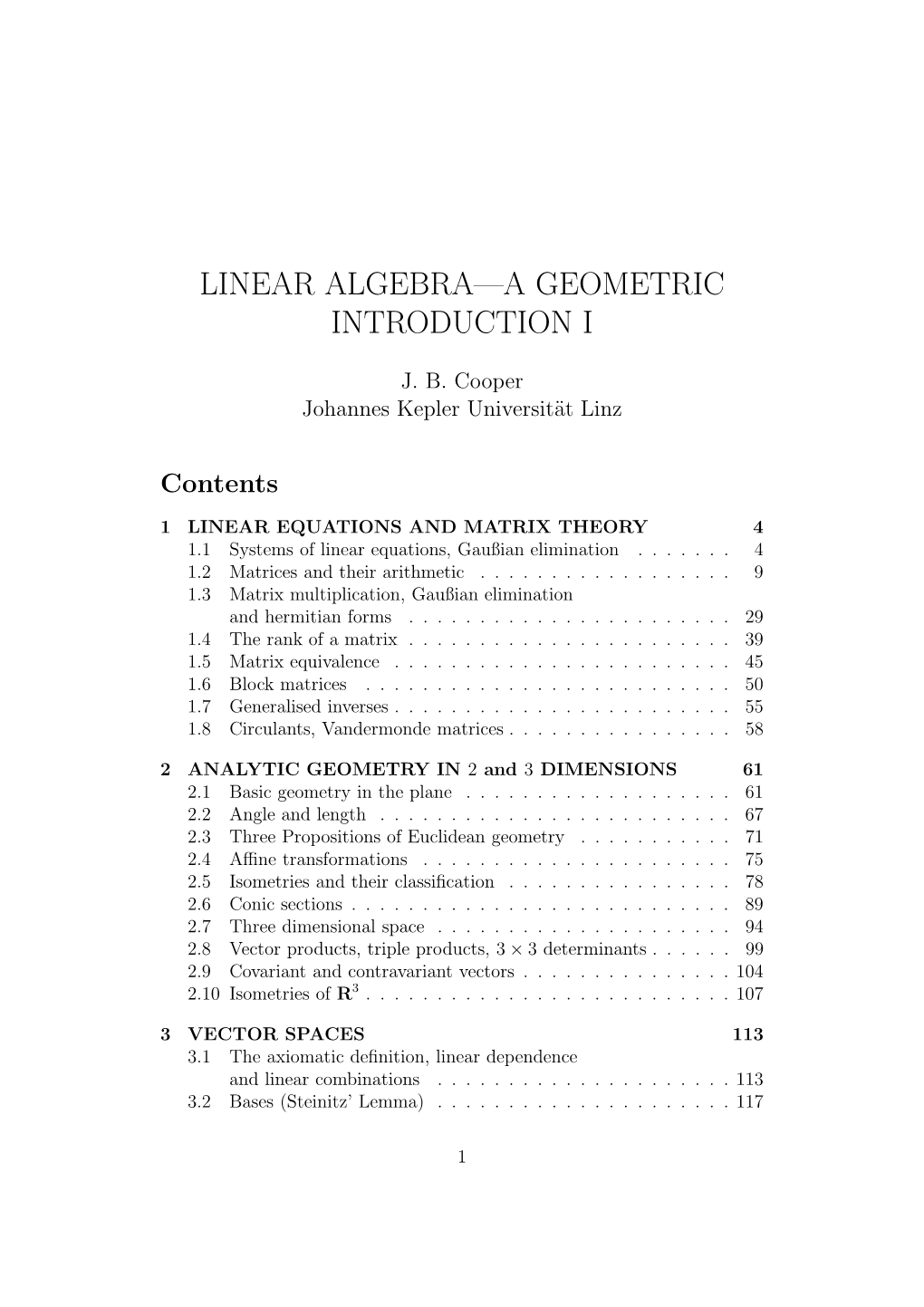

Linear Algebra—A Geometric Introduction I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things You Need to Know About Linear Algebra Math 131 Multivariate

the standard (x; y; z) coordinate three-space. Nota- tions for vectors. Geometric interpretation as vec- tors as displacements as well as vectors as points. Vector addition, the zero vector 0, vector subtrac- Things you need to know about tion, scalar multiplication, their properties, and linear algebra their geometric interpretation. Math 131 Multivariate Calculus We start using these concepts right away. In D Joyce, Spring 2014 chapter 2, we'll begin our study of vector-valued functions, and we'll use the coordinates, vector no- The relation between linear algebra and mul- tation, and the rest of the topics reviewed in this tivariate calculus. We'll spend the first few section. meetings reviewing linear algebra. We'll look at just about everything in chapter 1. Section 1.2. Vectors and equations in R3. Stan- Linear algebra is the study of linear trans- dard basis vectors i; j; k in R3. Parametric equa- formations (also called linear functions) from n- tions for lines. Symmetric form equations for a line dimensional space to m-dimensional space, where in R3. Parametric equations for curves x : R ! R2 m is usually equal to n, and that's often 2 or 3. in the plane, where x(t) = (x(t); y(t)). A linear transformation f : Rn ! Rm is one that We'll use standard basis vectors throughout the preserves addition and scalar multiplication, that course, beginning with chapter 2. We'll study tan- is, f(a + b) = f(a) + f(b), and f(ca) = cf(a). We'll gent lines of curves and tangent planes of surfaces generally use bold face for vectors and for vector- in that chapter and throughout the course. -

Schaum's Outline of Linear Algebra (4Th Edition)

SCHAUM’S SCHAUM’S outlines outlines Linear Algebra Fourth Edition Seymour Lipschutz, Ph.D. Temple University Marc Lars Lipson, Ph.D. University of Virginia Schaum’s Outline Series New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009, 2001, 1991, 1968 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior writ- ten permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-154353-8 MHID: 0-07-154353-8 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-154352-1, MHID: 0-07-154352-X. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please e-mail us at [email protected]. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. -

Determinants Math 122 Calculus III D Joyce, Fall 2012

Determinants Math 122 Calculus III D Joyce, Fall 2012 What they are. A determinant is a value associated to a square array of numbers, that square array being called a square matrix. For example, here are determinants of a general 2 × 2 matrix and a general 3 × 3 matrix. a b = ad − bc: c d a b c d e f = aei + bfg + cdh − ceg − afh − bdi: g h i The determinant of a matrix A is usually denoted jAj or det (A). You can think of the rows of the determinant as being vectors. For the 3×3 matrix above, the vectors are u = (a; b; c), v = (d; e; f), and w = (g; h; i). Then the determinant is a value associated to n vectors in Rn. There's a general definition for n×n determinants. It's a particular signed sum of products of n entries in the matrix where each product is of one entry in each row and column. The two ways you can choose one entry in each row and column of the 2 × 2 matrix give you the two products ad and bc. There are six ways of chosing one entry in each row and column in a 3 × 3 matrix, and generally, there are n! ways in an n × n matrix. Thus, the determinant of a 4 × 4 matrix is the signed sum of 24, which is 4!, terms. In this general definition, half the terms are taken positively and half negatively. In class, we briefly saw how the signs are determined by permutations. -

Span, Linear Independence and Basis Rank and Nullity

Remarks for Exam 2 in Linear Algebra Span, linear independence and basis The span of a set of vectors is the set of all linear combinations of the vectors. A set of vectors is linearly independent if the only solution to c1v1 + ::: + ckvk = 0 is ci = 0 for all i. Given a set of vectors, you can determine if they are linearly independent by writing the vectors as the columns of the matrix A, and solving Ax = 0. If there are any non-zero solutions, then the vectors are linearly dependent. If the only solution is x = 0, then they are linearly independent. A basis for a subspace S of Rn is a set of vectors that spans S and is linearly independent. There are many bases, but every basis must have exactly k = dim(S) vectors. A spanning set in S must contain at least k vectors, and a linearly independent set in S can contain at most k vectors. A spanning set in S with exactly k vectors is a basis. A linearly independent set in S with exactly k vectors is a basis. Rank and nullity The span of the rows of matrix A is the row space of A. The span of the columns of A is the column space C(A). The row and column spaces always have the same dimension, called the rank of A. Let r = rank(A). Then r is the maximal number of linearly independent row vectors, and the maximal number of linearly independent column vectors. So if r < n then the columns are linearly dependent; if r < m then the rows are linearly dependent. -

MATH 532: Linear Algebra Chapter 4: Vector Spaces

MATH 532: Linear Algebra Chapter 4: Vector Spaces Greg Fasshauer Department of Applied Mathematics Illinois Institute of Technology Spring 2015 [email protected] MATH 532 1 Outline 1 Spaces and Subspaces 2 Four Fundamental Subspaces 3 Linear Independence 4 Bases and Dimension 5 More About Rank 6 Classical Least Squares 7 Kriging as best linear unbiased predictor [email protected] MATH 532 2 Spaces and Subspaces Outline 1 Spaces and Subspaces 2 Four Fundamental Subspaces 3 Linear Independence 4 Bases and Dimension 5 More About Rank 6 Classical Least Squares 7 Kriging as best linear unbiased predictor [email protected] MATH 532 3 Spaces and Subspaces Spaces and Subspaces While the discussion of vector spaces can be rather dry and abstract, they are an essential tool for describing the world we work in, and to understand many practically relevant consequences. After all, linear algebra is pretty much the workhorse of modern applied mathematics. Moreover, many concepts we discuss now for traditional “vectors” apply also to vector spaces of functions, which form the foundation of functional analysis. [email protected] MATH 532 4 Spaces and Subspaces Vector Space Definition A set V of elements (vectors) is called a vector space (or linear space) over the scalar field F if (A1) x + y 2 V for any x; y 2 V (M1) αx 2 V for every α 2 F and (closed under addition), x 2 V (closed under scalar (A2) (x + y) + z = x + (y + z) for all multiplication), x; y; z 2 V, (M2) (αβ)x = α(βx) for all αβ 2 F, (A3) x + y = y + x for all x; y 2 V, x 2 V, (A4) There exists a zero vector 0 2 V (M3) α(x + y) = αx + αy for all α 2 F, such that x + 0 = x for every x; y 2 V, x 2 V, (M4) (α + β)x = αx + βx for all (A5) For every x 2 V there is a α; β 2 F, x 2 V, negative (−x) 2 V such that (M5)1 x = x for all x 2 V. -

On the History of Some Linear Algebra Concepts:From Babylon to Pre

The Online Journal of Science and Technology - January 2017 Volume 7, Issue 1 ON THE HISTORY OF SOME LINEAR ALGEBRA CONCEPTS: FROM BABYLON TO PRE-TECHNOLOGY Sinan AYDIN Kocaeli University, Kocaeli Vocational High school, Kocaeli – Turkey [email protected] Abstract: Linear algebra is a basic abstract mathematical course taught at universities with calculus. It first emerged from the study of determinants in 1693. As a textbook, linear algebra was first used in graduate level curricula in 1940’s at American universities. In the 2000s, science departments of universities all over the world give this lecture in their undergraduate programs. The study of systems of linear equations first introduced by the Babylonians around at 1800 BC. For solving of linear equations systems, Cardan constructed a simple rule for two linear equations with two unknowns around at 1550 AD. Lagrange used matrices in his work on the optimization problems of real functions around at 1750 AD. Also, determinant concept was used by Gauss at that times. Between 1800 and 1900, there was a rapid and important developments in the context of linear algebra. Some theorems for determinant, the concept of eigenvalues, diagonalisation of a matrix and similar matrix concept were added in linear algebra by Couchy. Vector concept, one of the main part of liner algebra, first used by Grassmann as vector product and vector operations. The term ‘matrix’ as a rectangular forms of scalars was first introduced by J. Sylvester. The configuration of linear transformations and its connection with the matrix addition, multiplication and scalar multiplication were studied first by A. -

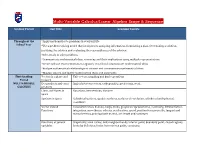

Multi-Variable Calculus/Linear Algebra Scope & Sequence

Multi-Variable Calculus/Linear Algebra Scope & Sequence Grading Period Unit Title Learning Targets Throughout the *Apply mathematics to problems in everyday life School Year *Use a problem-solving model that incorporates analyzing information, formulating a plan, determining a solution, justifying the solution and evaluating the reasonableness of the solution *Select tools to solve problems *Communicate mathematical ideas, reasoning and their implications using multiple representations *Create and use representations to organize, record and communicate mathematical ideas *Analyze mathematical relationships to connect and communicate mathematical ideas *Display, explain and justify mathematical ideas and arguments First Grading Vectors in a plane and Unit vectors, graphing and basic operations Period in space MULTIVARIABLE Dot products and cross Angles between vectors, orthogonality, projections, work CALCULUS products Lines and Planes in Equations, intersections, distance space Surfaces in Space Cylindrical surfaces, quadric surfaces, surfaces of revolution, cylindrical and spherical coordinate Vector Valued Parameterization, domain, range, limits, graphical representation, continuity, differentiation, Functions integration, smoothness, velocity, acceleration, speed, position for a projectile, tangent and normal vectors, principal unit normal, arc length and curvature. Functions of several Graphically, level curves, delta neighborhoods, interior point, boundary point, closed regions, variables limits by definition, limits from various -

MATH 304 Linear Algebra Lecture 6: Transpose of a Matrix. Determinants. Transpose of a Matrix

MATH 304 Linear Algebra Lecture 6: Transpose of a matrix. Determinants. Transpose of a matrix Definition. Given a matrix A, the transpose of A, denoted AT , is the matrix whose rows are columns of A (and whose columns are rows of A). That is, T if A = (aij ) then A = (bij ), where bij = aji . T 1 4 1 2 3 Examples. = 2 5, 4 5 6 3 6 T 7 T 4 7 4 7 8 = (7, 8, 9), = . 7 0 7 0 9 Properties of transposes: • (AT )T = A • (A + B)T = AT + BT • (rA)T = rAT • (AB)T = BT AT T T T T • (A1A2 ... Ak ) = Ak ... A2 A1 • (A−1)T = (AT )−1 Definition. A square matrix A is said to be symmetric if AT = A. For example, any diagonal matrix is symmetric. Proposition For any square matrix A the matrices B = AAT and C = A + AT are symmetric. Proof: BT = (AAT )T = (AT )T AT = AAT = B, C T = (A + AT )T = AT + (AT )T = AT + A = C. Determinants Determinant is a scalar assigned to each square matrix. Notation. The determinant of a matrix A = (aij )1≤i,j≤n is denoted det A or a11 a12 ... a1n a a ... a 21 22 2n . .. an1 an2 ... ann Principal property: det A =0 if and only if the matrix A is singular. Definition in low dimensions a b Definition. det (a) = a, = ad − bc, c d a a a 11 12 13 a21 a22 a23 = a11a22a33 + a12a23a31 + a13a21a32− a31 a32 a33 −a13a22a31 − a12a21a33 − a11a23a32. * ∗ ∗ ∗ * ∗ ∗ ∗ * +: ∗ * ∗ , ∗ ∗ * , * ∗ ∗ . ∗ ∗ * * ∗ ∗ ∗ * ∗ ∗ ∗ * ∗ * ∗ * ∗ ∗ − : ∗ * ∗ , * ∗ ∗ , ∗ ∗ * . * ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ * ∗ * ∗ Examples: 2×2 matrices 1 0 3 0 = 1, = − 12, 0 1 0 −4 −2 5 7 0 = − 6, = 14, 0 3 5 2 0 −1 0 0 = 1, = 0, 1 0 4 1 −1 3 2 1 = 0, = 0. -

MATH 423 Linear Algebra II Lecture 38: Generalized Eigenvectors. Jordan Canonical Form (Continued)

MATH 423 Linear Algebra II Lecture 38: Generalized eigenvectors. Jordan canonical form (continued). Jordan canonical form A Jordan block is a square matrix of the form λ 1 0 ··· 0 0 . 0 λ 1 .. 0 0 . 0 0 λ .. 0 0 J = . . .. .. . 0 0 0 .. λ 1 0 0 0 ··· 0 λ A square matrix B is in the Jordan canonical form if it has diagonal block structure J1 O . O O J2 . O B = . , . .. O O . Jk where each diagonal block Ji is a Jordan block. Consider an n×n Jordan block λ 1 0 ··· 0 0 . 0 λ 1 .. 0 0 . 0 0 λ .. 0 0 J = . . .. .. . 0 0 0 .. λ 1 0 0 0 ··· 0 λ Multiplication by J − λI acts on the standard basis by a chain rule: 0 e1 e2 en−1 en ◦ ←− • ←− •←−··· ←− • ←− • 2 1 0000 0 2 0000 0 0 3 0 0 0 Consider a matrix B = . 0 0 0 3 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 This matrix is in Jordan canonical form. Vectors from the standard basis are organized in several chains. Multiplication by B − 2I : 0 e1 e2 ◦ ←− • ←− • Multiplication by B − 3I : 0 e3 ◦ ←− • 0 e4 e5 e6 ◦ ←− • ←− • ←− • Generalized eigenvectors Let L : V → V be a linear operator on a vector space V . Definition. A nonzero vector v is called a generalized eigenvector of L associated with an eigenvalue λ if (L − λI)k (v)= 0 for some integer k ≥ 1 (here I denotes the identity map on V ). The set of all generalized eigenvectors for a particular λ along with the zero vector is called the generalized eigenspace and denoted Kλ. -

Eigenvalues, Eigenvectors, and Eigenspaces of Linear Operators

Therefore x + cy is also a λ-eigenvector. Thus, the set of λ-eigenvectors form a subspace of F n. q.e.d. One reason these eigenvalues and eigenspaces are important is that you can determine many of the Eigenvalues, eigenvectors, and properties of the transformation from them, and eigenspaces of linear operators that those properties are the most important prop- Math 130 Linear Algebra erties of the transformation. D Joyce, Fall 2015 These are matrix invariants. Note that the Eigenvalues and eigenvectors. We're looking eigenvalues, eigenvectors, and eigenspaces of a lin- at linear operators on a vector space V , that is, ear transformation were defined in terms of the linear transformations x 7! T (x) from the vector transformation, not in terms of a matrix that de- space V to itself. scribes the transformation relative to a particu- When V has finite dimension n with a specified lar basis. That means that they are invariants of basis β, then T is described by a square n×n matrix square matrices under change of basis. Recall that A = [T ]β. if A and B represent the transformation with re- We're particularly interested in the study the ge- spect to two different bases, then A and B are con- ometry of these transformations in a way that we jugate matrices, that is, B = P −1AP where P is can't when the transformation goes from one vec- the transition matrix between the two bases. The tor space to a different vector space, namely, we'll eigenvalues are numbers, and they'll be the same compare the original vector x to its image T (x). -

Generalized Eigenvector - Wikipedia

11/24/2018 Generalized eigenvector - Wikipedia Generalized eigenvector In linear algebra, a generalized eigenvector of an n × n matrix is a vector which satisfies certain criteria which are more relaxed than those for an (ordinary) eigenvector.[1] Let be an n-dimensional vector space; let be a linear map in L(V), the set of all linear maps from into itself; and let be the matrix representation of with respect to some ordered basis. There may not always exist a full set of n linearly independent eigenvectors of that form a complete basis for . That is, the matrix may not be diagonalizable.[2][3] This happens when the algebraic multiplicity of at least one eigenvalue is greater than its geometric multiplicity (the nullity of the matrix , or the dimension of its nullspace). In this case, is called a defective eigenvalue and is called a defective matrix.[4] A generalized eigenvector corresponding to , together with the matrix generate a Jordan chain of linearly independent generalized eigenvectors which form a basis for an invariant subspace of .[5][6][7] Using generalized eigenvectors, a set of linearly independent eigenvectors of can be extended, if necessary, to a complete basis for .[8] This basis can be used to determine an "almost diagonal matrix" in Jordan normal form, similar to , which is useful in computing certain matrix functions of .[9] The matrix is also useful in solving the system of linear differential equations where need not be diagonalizable.[10][11] Contents Overview and definition Examples Example 1 Example 2 Jordan chains -

Generalized Eigenvectors, Minimal Polynomials and Theorem of Cayley-Hamiltion

GENERALIZED EIGENVECTORS, MINIMAL POLYNOMIALS AND THEOREM OF CAYLEY-HAMILTION FRANZ LUEF Abstract. Our exposition is inspired by S. Axler’s approach to linear algebra and follows largely his exposition in ”Down with Determinants”, check also the book ”LinearAlgebraDoneRight” by S. Axler [1]. These are the lecture notes for the course of Prof. H.G. Feichtinger ”Lineare Algebra 2” from 15.11.2006. Before we introduce generalized eigenvectors of a linear transformation we recall some basic facts about eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a linear transformation. Let V be a n-dimensional complex vector space. Recall a complex number λ is called an eigenvalue of a linear operator T on V if T − λI is not injective, i.e. ker(T − λI) 6= {0}. The main result about eigenvalues is that every linear op- erator on a finite-dimensional complex vector space has an eigenvalue! Furthermore we call a vector v ∈ V an eigenvector of T if T v = λv for some eigenvalue λ. The central result on eigenvectors is that Non-zero eigenvectors corresponding to distinct eigenvalues of a linear transformation on V are linearly independent. Consequently the number of distinct eigenvalues of T can- not exceed thte dimension of V . Unfortunately the eigenvectors of T need not span V . For example the linear transformation on C4 whose matrix is 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 T = 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 as only the eigenvalue 0, and its eigenvectors form a one-dimensional subspace of C4. Observe that T,T 2 6= 0 but T 3 = 0.