Water Sharing Schemes: Insights from Canterbury and Otago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEN33 CSI Fish & Game Opihi River Flyer

ACCESS ETIQUETTE • No dogs • No guns Opihi River • No camping • Leave gates as you find them • Stay within the river margins • Do not litter • Respect private property • Avoid disturbing stock or damaging crops • Do not park vehicles in gateways • Be courteous to local landowners and others Remember the reputation of ALL anglers is reflected by your actions FISHING ETIQUETTE • Respect other anglers already on the water • Enquire politely about their fishing plans • Start your angling in the opposite direction • Refer to your current Sports Fishing Guide for fishing regulations and bag limits A successful angler on the Opihi River Pamphlet published in 2005 Central South Island Region Cover Photo: Lower Opihi River upstream of 32 Richard Pearse Drive, PO Box 150, Temuka, New Zealand State Highway 1 Bridge Telephone (03) 615 8400, Facsimile (03) 615 8401 Photography: by G. McClintock Corporate Print, Timaru Central South Island Region THE OPIHI RIVER Chinook salmon migrate into the Opihi River ANGLING INFORMATION usually in February and at this time the fishing pressure in the lower river increases significantly. FISHERY The Opihi River supports good populations of As a result of warm nor-west rain and snow melt both chinook salmon and brown trout. In the The Opihi River rises in a small modified wetland waters from the mouth to about the State of approximately 2 hectares at Burkes Pass and the larger Rakaia and Rangitata Rivers often flood and during these times the spring fed Opihi Highway 1 bridge there is a remnant population flows in an easterly direction for about 80 km to of rainbow trout, survivors of Acclimatisation enter the Pacific Ocean 10 km east of Temuka. -

Ecosystem Services Review of Water Storage Projects in Canterbury: the Opihi River Case

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln University Research Archive Ecosystem Services Review of Water Storage Projects in Canterbury: The Opihi River Case By Dr Edward J. S. Hearnshaw1, Prof Ross Cullen1 and Prof Ken F. D. Hughey2 1Faculty of Commerce and 2Faculty of Environment, Society and Design Lincoln University, New Zealand 2 Contents Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 6 2.0 Ecosystem Services 9 3.0 The Opihi River and the Opuha Dam 12 4.0 Ecosystem Services Hypotheses 17 4.1 Hypotheses of Provisioning Ecosystem Services 17 4.2 Hypotheses of Regulating Ecosystem Services 19 4.3 Hypotheses of Cultural Ecosystem Services 20 5.0 Ecosystem Services Indicators 25 5.1 Indicators of Provisioning Ecosystem Services 27 5.2 Indicators of Regulating Ecosystem Services 36 5.3 Indicators of Cultural Ecosystem Services 44 6.0 Discussion 49 6.1 Ecosystem Services Index Construction 51 6.2 Future Water Storage Projects 56 7.0 Acknowledgements 58 8.0 References 59 3 4 Ecosystem Services Review of Water Storage Projects in Canterbury: The Opihi River Case By Dr Edward J. S. Hearnshaw1, Prof Ross Cullen1 and Prof Ken F. D. Hughey2 1Commerce Faculty and 2Environment, Society and Design Faculty, Lincoln University, New Zealand When the well runs dry we know the true value of water Benjamin Franklin Executive Summary There is an ever‐increasing demand for freshwater that is being used for the purposes of irrigation and land use intensification in Canterbury. But the impact of this demand has lead to unacceptable minimum river flows. -

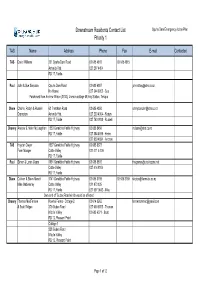

140828 Tas Update TRM.Xlsx

Downstream Residents Contact List Opuha Dam Emergency Action Plan Priority 1 TAS Name Address Phone Fax E-mail Contacted TAS David Williams 231 Opuha Dam Road 03 685 4818 03 685 4815 Ashwick Flat 027 297 4454 RD 17, Fairlie Paul John & Sue Simpson Opuha Dam Road 03 680 6897 [email protected] No House 027 344 8902 - Sue Purchased from Andrew Wilson (2013), Lives in cottage Mt Hay Station, Tekapo Diane Charlie, Robyn & Russell 62 Trentham Road 03 685 4858 [email protected] Crampton Ashwick Flat 027 233 4364 - Robyn RD 17, Fairlie 027 740 9988 - Russell Chonny Andrew & Helen McLaughlan 1283 Geraldine Fairlie Highway 03 685 8456 [email protected] RD 17, Fairlie 027 354 4698 - Helen 027 950 4894 - Andrew TAS Hayden Dwyer 1537 Geraldine Fairlie Highway 03 685 8673 Farm Maager Cattle Valley 027 471 5 736 RD 17, Fairlie Paul Simon & Loren Geary 1891 Geraldine Fairlie Highway 03 685 8815 [email protected] Cattle Valley 027 414 8104 RD 17, Fairlie Diane Colleen & Steve Marett 1741 Geraldine Fairlie Highway 03 685 8789 03 685 8789 [email protected] Mike Mabwinney Cattle Valley 021 873 835 RD 17, Fairlie 027 507 9642 - Mike Own land off Gudex Road which would be affected Chonny Thomas MacFarlane Kowhai Farms - Cottage 2 03 614 8262 [email protected] & Scott Ridgen 379 Gudex Road 027 600 8555 - Thomas Middle Valley 03 685 6071 - Scott RD 12, Pleasant Point Cottage 1 238 Gudex Road Middle Valley RD 12, Pleasant Point Page 1 of 12 Downstream Residents Contact List Opuha Dam Emergency Action Plan Priority 1 TAS Name Address -

Washdyke Lagoon WILDLIFE REFUGE

Phar Lap RaceRacewaway TO CHRISTCHURCH 1 Washdyke Industrial Area Washdyke Lagoon WILDLIFE REFUGE Y LE GOD BEAUMONT E ELLESMER GRANTLEA L Dashing RockRockss OCH ALPI NE E R 1 N AINVIEW Walkway MOUNT EV ERS L EY VILLAGE C GLAM L Gleniti YD STIRLIN E I C S MOOR AR G R LINCOL E D E BALMORAL IN B N U E BRAEMA CLIMI R G H A R R G Y L E SHORT R B CEDA E LL B IR D Highfield Aorangi PaParkrk Ashbury Park Blackett’s O RI Golf Course E Southern TrTrusust Lighthouse L SDALE PARK VIEW T ELM O I H N NU S U Events Centre RAI EY XL UK R L OXBUR W E GH O Y L WAI L O JONAS WI N ON R O M CH TH CA AW A H M TE PB WA A HA E IP U LL O HILLSDE R RT I ST JOHN’S C N W O L OO PrimePort LIN LYSAGHT D ANSCOMBE G BR KARAKA BA Centennial Y HILL Park Westend PAIGNTON THE TERRA H U CE G PaParkrk GUTHRIE H THOMAS Lough PaParkrk C H i SHERRATT A P gy E Alpine Ener L DE T A STUAR L W E L L I N G T SchoolSc O hool Park N W Sacred Heart A TLINT L BasilicaBasilica IN R G U S HectorHectorss T S O E N L O’NEILO’N L L VINNELVINNELL M Coastal E BABBING E I M LL ORIAO R I T A L alklkway E WWa S ERSR A M V SOSO E M A RK Botanic ET Gardens TAY LOR K K E E R PPaatitititi I I I CH T T CAMPBELL H H A R D CBay PPooolol S CemeteCemetery Point Caroline Bay COOPERS 1 Saltwater S I MMO RedruthRedruth PaParrkk H Penguin NS AR Boardwalkalkss Creek Walkway T Viewing Skateboard Park Mini Golf Area BEVERLEY HILL Aviary Disc Golf Soundshell PrimePort BA Y HILLPIAZZA Otipua Wetlands Tuhawaiki JackJacks Point BA TO DUNEDIN YVIEW Supermarket Pharmacy Bus Station Hospital CBay Pool Dog Park BusBu -

South Island Fishing Regulations for 2020

Fish & Game 1 2 3 4 5 6 Check www.fishandgame.org.nz for details of regional boundaries Code of Conduct ....................................................................4 National Sports Fishing Regulations ...................................... 5 First Schedule ......................................................................... 7 1. Nelson/Marlborough .......................................................... 11 2. West Coast ........................................................................16 3. North Canterbury ............................................................. 23 4. Central South Island ......................................................... 33 5. Otago ................................................................................44 6. Southland .........................................................................54 The regulations printed in this guide booklet are subject to the Minister of Conservation’s approval. A copy of the published Anglers’ Notice in the New Zealand Gazette is available on www.fishandgame.org.nz Cover Photo: Jaymie Challis 3 Regulations CODE OF CONDUCT Please consider the rights of others and observe the anglers’ code of conduct • Always ask permission from the land occupier before crossing private property unless a Fish & Game access sign is present. • Do not park vehicles so that they obstruct gateways or cause a hazard on the road or access way. • Always use gates, stiles or other recognised access points and avoid damage to fences. • Leave everything as you found it. If a gate is open or closed leave it that way. • A farm is the owner’s livelihood and if they say no dogs, then please respect this. • When driving on riverbeds keep to marked tracks or park on the bank and walk to your fishing spot. • Never push in on a pool occupied by another angler. If you are in any doubt have a chat and work out who goes where. • However, if agreed to share the pool then always enter behind any angler already there. • Move upstream or downstream with every few casts (unless you are alone). -

Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Water Zone Management Committee

ORARI-TEMUKA-OPIHI-PAREORA WATER ZONE MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE on Monday 5 September 2016 3pm Council Chamber Timaru District Council Timaru ORARI-OPIHI-PAREORA WATER ZONE MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Notice is hereby given that an Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Water Zone Management Committee meeting will be held on Monday 5 September 2016 at 3pm in the Council Chamber, Timaru District Council, 2 King George Place, Timaru. Committee Members: John Talbot (Chairman), David Caygill, Kylee Galbraith, John Henry, Mandy Home, Ivon Hurst, Richard Lyon, Hamish McFarlane, James Pearse, Ad Sintenie, Mark Webb and Evan Williams ORARI-TEMUKA-OPIHI-PAREORA WATER ZONE MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 1 Apologies 2 Register of Interest 3 1 Confirmation of Minutes 4 Facilitator Update 5 Community Forum 6 6 Catchment Group Update 7 Washdyke Taskforce Update 8 Groundwater ecosystems: What’s living in our groundwater? 9 8 Immediate Steps Biodiversity Projects 10 18 Immediate Steps Biodiversity Fund Review 11 Level of Protection/Security of Water Supplies in OTOP Zone – TDC Water Services Operations Engineer 12 Regional Committee Update 13 Close ORARI-TEMUKA-OPIHI-PAREORA WATER ZONE MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE FOR THE MEETING OF 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 Report for Agenda Item No 3 Prepared by Joanne Brownie Secretary Confirmation of Minutes – Committee Meeting 1 August 2016 ___________________________ Minutes of the August Committee meeting. Recommendation That the minutes of the Committee meeting held on 1 August 2016, be confirmed as a true and correct record. 5 September 2016 -

Water Resource Summary: Pareora-Waihao

Pareora – Waihao River: Water Resource Summary Report No. R06/20 ISBN 1-86937-602-1 note CHAPTER 5 DRAFT - not ready Prepared by Philippa Aitchison-Earl Marc Ettema Graeme Horrell Alistair McKerchar Esther Smith August 2005 1 Report R06/20, ISBN 1-86937-602-1 58 Kilmore Street PO Box 345 Christchurch Phone (03) 365 3828 Fax (03) 365 3194 75 Church Street PO Box 550 Timaru Phone (03) 688 9069 Fax (03) 688 9067 Website: www.ecan.govt.nz Customer Services Phone 0800 324 636 2 Executive summary The water resources of the rivers and associated groundwater resources draining The Hunters Hills in South Canterbury are described and quantified. These rivers include the Pareora River in the north and the Waihao River in the south, and those between. None of the rivers is large and while they sometimes flood, their usual state is to convey very low flows. Given the population in the region, including Timaru which takes much of its water supply from the upper Pareora River, the region is arguably the most water deficient in the country. More than 100 years of record are available for several raingauges in the region. Mean annual rainfalls are less than 600 mm on the coast, increasing to about 1200 mm at higher points in The Hunters Hills. Monthly rainfalls show a slight tendency toward lower values in winter months. Typical (median) monthly totals range from about 25 mm to about 80 mm. Particularly dry periods occurred in 1914-1916, 1984-1985, 1989-1999 and 2001 to 2003. Since 1996, annual rainfalls have exceeded the mean annual values in only two or three years. -

Opuha-Water-Limited-Evidence.Pdf

BEFORE INDEPENDANT HEARING COMMISSIONERS APPOINTED BY THE MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL UNDER the Resource Management Act 1991 IN THE MATTER OF submissions by Opuha Water Limited on Proposed Plan Change 18 to the Mackenzie District Plan (Indigenous Biodiversity) STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF JULIA MARGARET CROSSMAN FOR OPUHA WATER LIMITED (SUBMITTER #14) Dated: 12 February 2021 _________________________________________________________________ GRESSON DORMAN & CO Solicitors PO Box 244, Timaru 7940 Telephone 03 687 8004 Facsimile 03 684 4584 Solicitor acting: G C Hamilton / N A Hornsey [email protected] / [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 My name is Julia Margaret Crossman. I am the Environmental Manager of Opuha Water Limited (OWL), a position I have held since January 2014. 1.2 I hold a Bachelor of Applied Science, majoring in Environmental Management (First Class Honours) from Otago University, and a Master of Resource and Environment Planning (First Class Honours) from Massey University. I also hold a Certificate of Completion (Intermediate) in Sustainable Nutrient Management in New Zealand Agriculture from Massey University. 1.3 My current role involves consent management for OWL, including the management of new consent applications and compliance monitoring. Prior to my work at OWL, I held various roles at ECan for a period of nine years, including Resource Care Co-ordinator (Land Management section), Community Facilitator for the Planning Section where I was involved in the Orari and Selwyn-Waihora Sub-Regional Planning Processes, and Project Manager and Lead Planner for the Waitaki Sub-Regional Planning Process. 1.4 OWLimited made a submission and further submissions on Plan Change 18 to the Mackenzie District Plan (PC18). -

Dear Tavisha We Act for Opuha Water Limited (OWL), Submitter No. PC7

From: Georgina Hamilton To: Plan Hearings Cc: Glenire Farm; "Andrew Mockford"; Julia Crossman; Greg Ryder; Richard Measures; Keri Johnston; Tim Ensor Subject: Plan Change 7: Opuha Water Limited - Evidence Date: Friday, 17 July 2020 5:22:45 pm Attachments: Evidence in chief of Ryan O"Sullivan (OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Evidence in Chief of Andrew Mockford (OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Evidence in Chief of Julia Crossman (OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Quick reference guide (Annexure A to Evidence in Chief of Julia Crossman (OWL)).pdf Evidence in Chief of Richard Measures (OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Evidence in Chief of Keri Johnston (OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Evidence in Chief of Dr Gregory Ryder (AMWG & OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Evidence in Chief of Tim Ensor (OWL) 17.7.20.pdf Dear Tavisha We act for Opuha Water Limited (OWL), submitter no. PC7-381. We attach for filing, in relation to the above matter, statements of evidence in chief of the following witnesses on behalf of OWL: 1. Ryan O’Sullivan (OWL Board Chair) 2. Andrew Mockford (OWL CEO) 3. Julia Crossman (OWL Environmental Manager) 4. Dr Greg Ryder (Lake Opuha - water quality) – note this statement of evidence addresses matters also pertaining to the submissions of the Adaptive Management Working Group (AMWG) and has also been filed with other AMWG evidence today. 5. Richard Measures (water quality) 6. Keri Johnston (hydrology/allocation) 7. Tim Ensor (planning) We note that: Annexure A to the evidence of Ms Crossman comprises a “Quick Reference Guide” providing a location map and key information regarding the Opuha Scheme. -

Council Meeting Held on 12/11/2018

Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Zone Implementation Programme Addendum Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Zone Implementation Programme Addendum 1 Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Zone Implementation Programme Addendum This page is intentionally left blank 2 Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Zone Implementation Programme Addendum Contents 1.0 Purpose 8 2.0 Background 10 2.1 Zone Description 10 2.2 Zone Implementation Programme 10 2.3 Collaboration 12 2.4 Drivers for Change 12 2.5 Pathways for Change 18 3.0 Current State of the OTOP Zone 20 3.1 Key Questions 23 4.0 Zone-Wide Recommendations 26 4.1 Catchment Groups 26 4.2 Drinking Water Supplies 26 4.3 Recognition and Protection of Culturally Significant Sites 29 4.5 Protection and Enhancement of Biodiversity 33 4.6 Forestry and Water Yield 39 4.7 Protection of Upper Catchments 41 4.8 Water Quality and Ecosystem Health 42 4.9 Water Quantity 52 5.0 FMU Specific Recommendations 58 5.1 Orari Freshwater Management Unit 58 5.2 Temuka Freshwater Management Unit 62 5.3 Opihi Freshwater Management Unit 68 5.4 Timaru Freshwater Management Unit 84 5.5 Pareora Freshwater Management Unit 89 3 Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Zone Implementation Programme Addendum List of Figures Figure 1: Outline of NPS-FM National Objectives Framework ............................................. 15 List of Maps Map 1: Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Healthy Catchments Project Area .............................. 11 Map 2: Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Freshwater Management Units .................................. 13 Map 3: Opihi and Waitarakao Mātaitai Reserves ................................................................. 16 Map 4: Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Groundwater Allocation Zones .................................. 21 Map 5: Limestone in the Orari-Temuka-Opihi-Pareora Zone .............................................. -

Jet Boating on Canterbury Rivers – 2015

5 October 2015 Jet Boating on Canterbury Rivers – 2015 Environment Canterbury Rob Greenaway Rob Gerard Ken Hughey 2 Jet Boating on Canterbury Rivers – 2015 Prepared for Environment Canterbury by Rob Greenaway – Rob Greenaway & Associates Rob Gerard – Jet Boating New Zealand Ken Hughey – Lincoln University 5 October 2015 Version status: Final Cover photo: Waiau River family boating. Rob Greenaway Environment Canterbury – Jet Boating on Canterbury Rivers 3 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 4 2 History ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 The boats ....................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Participation ................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Commercial jet boating ................................................................................................ 10 2.4 Jet Boating New Zealand ............................................................................................. 12 2.5 Jet boat events ............................................................................................................. 13 2.6 Jet boating -

Arowhenua Contaminants Report-Data-Final

Contaminants in kai – Arowhenua rohe Part 1: Data Report NIWA Client Report: HAM2010-105 October 2010 NIWA Project: HRC08201 Contaminants in Kai – Arowhenua rohe Part 1: Data Report Michael Stewart Greg Olsen Ngaire Phillips Chris Hickey NIWA contact/Corresponding author Michael Stewart Prepared for Te Runanga o Arowhenua & Health Research Council of New Zealand NIWA Client Report: HAM2010-105 October 2010 NIWA Project: HRC08201 National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd Gate 10, Silverdale Road, Hamilton P O Box 11115, Hamilton, New Zealand Phone +64-7-856 7026, Fax +64-7-856 0151 www.niwa.co.nz All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the client. Such permission is to be given only in accordance with the terms of the client's contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Contents Executive Summary iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Methods 3 2.1 Survey design 3 2.2 Kai consumption survey 3 2.3 Sampling Design 4 2.3.1 Site and kai information 4 2.3.2 Contaminants of concern 7 2.3.3 Proposed sites of collection and types of kai 10 2.4 Sample preparation 12 2.5 Analysis of contaminants in kai and sediment 12 2.6 Analysis of mercury in hair 13 2.7 Arowhenua consumption data 14 3. Results and discussion 15 3.1 Sampling 15 3.2 Arowhenua consumption data 17 3.3 Mercury in hair 18 3.4 Arowhenua contamination data 20 3.4.1 Organochlorine pesticides 20 3.4.2 PCBs 22 3.4.3 Heavy metals 26 3.5 Site contamination comparisons 33 4.