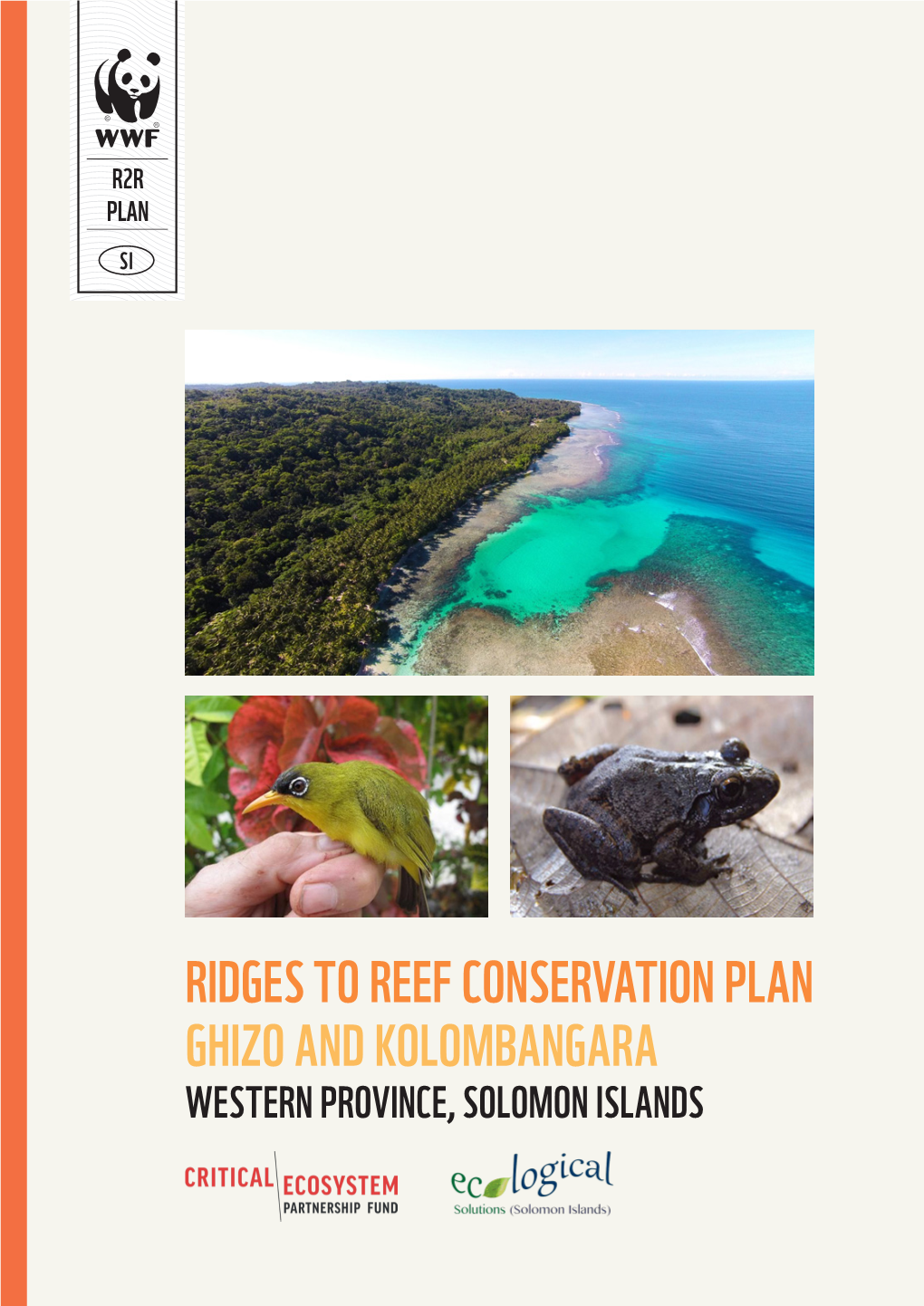

Ridges to Reef Conservation Plan Ghizo and Kolombangara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENSURING SUSTAINABLE COASTAL COMMUNITIES a CASE STUDY on SOLOMON ISLANDS Front Cover: Western Province

ENSURING SUSTAINABLE COASTAL COMMUNITIES A CASE STUDY ON SOLOMON ISLANDS Front cover: Western Province. A healthy island ecosystem. © DAVID POWER Our Vision: The people of Solomon Islands managing their natural resources for food security, livelihoods and a sustainable environment. “Olketa pipol lo Solomon Islands lukaotim gud olketa samting lo land an sea fo kaikai, wokim seleni, an gudfala place fo stap.” Published by: WWF-Pacifc (Solomon Islands) P.O.Box 1373, Honiara Hotel SOLOMON ISLANDS TEL: +677 28023 EMAIL: [email protected] March 2017 Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. All rights reserved. WRITTEN BY Nicole Lowrey DESIGN BY Alana McCrossin PHOTOS @ Nicole Lowrey / David Power / Andrew Smith SPECIAL THANKS TO WWF staf Shannon Seeto, Salome Topo, Jackie Thomas, Andrew Smith, Minnie Rafe, Zeldalyn Hilly, Richard Makini and Nicoline Poulsen for providing information for the report and facilitating feld trips. FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, or if you would like to donate, please send an email to Shannon Seeto at WWF-Pacifc (Solomon Islands): [email protected] The WWF-Pacifc (Solomon Islands) Sustainable Coastal Communities Programme is supported by the Australian Government, John West Australia, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF), USAID REO, private Australian donors and WWF supporters in Australia and the Netherlands. This publication is made possible by support from the Coral Triangle Program. CONTENTS 3 A unique -

Social Assessment

Social Assessment Project Title: Western Province Ridges to Reef: Planning to Enhance the Conservation of Biodiversity Conservation Plan Applicant: World Wide Fund for Nature, Solomon Islands Because the project will implement activities in areas with Indigenous Peoples, a Social Assessment has been prepared, to demonstrate how the project will comply with CEPF’s Safeguard Policy on Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples in the project area A total of 18 indigenous tribes are known within the proposed project area of Kolombangara Island. However, the below list will be confirmed during consultation meetings with KIBCA (Kolombangara Island Biodiversity and Conservation Association), communities, other local partners, and stakeholders within the project site. Therefore, the list below may increase or decrease after the consultation meetings. KIBCA reports that approximately 6,000 people currently reside on Kolombangara Island 1. Koloma 2. Ngava 3. Vumba 4. Qoza 5. Kona 6. Sarelata 7. Paleka 8. Kumbongava 9. Bantongo 10. Jito 11. Siporae 12. Sikipozo 13. Padezaka 14. Matakale 15. Vasiluku 16. Sirebe 17. Vuri 18. Leanabako If funds permit, some awareness activities may also be carried out on Ghizo Island. Over the years, people from other islands/countries have either settled on or have been relocated to Ghizo Island for a host of reasons. Identifying indigenous peoples within the project area is thus a rather complicated task. Eleven major rural/semi-rural communities exist on Ghizo Island, excluding the town of Gizo itself. Saeraghi, Vorivori and Bibolo are descendants of the original settlers and owners of Ghizo Island. Paeloge and Suvania/Simboro settlers are immigrants from Simbo Island. -

Land and Maritime Connectivity Project: Road Component Initial

Land and Maritime Connectivity Project (RRP SOL 53421-001) Initial Environmental Examination Project No. 53421-001 Status: Draft Date: August 2020 Solomon Islands: Land and Maritime Connectivity Project – Multitranche Financing Facility Road Component Prepared by Ministry of Infrastructure Development This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to any particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Solomon Islands: Land and Maritime Connectivity Project Road Component – Initial Environmental Examination Table of Contents Abbreviations iv Executive Summary v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to the Project 1 1.2 Scope of the Environmental Assessment 5 2 Legal and Institutional Framework 6 2.1 Legal and Planning Framework 6 2.1.1 Country safeguard system 6 2.1.2 Other legislation supporting the CSS 7 2.1.3 Procedures for implementing the CSS 9 2.2 National Strategy and Plans 10 2.3 Safeguard Policy Statement 11 3 Description of the Subprojects 12 3.1 Location and Existing Conditions – SP-R1 12 3.1.1 Existing alignment 12 3.1.2 Identified issues and constraints 14 3.2 Location and Existing Conditions – SP-R5 15 3.2.1 Location -

Recent Dispersal Events Among Solomon Island Bird Species Reveal Differing Potential Routes of Island Colonization

Recent dispersal events among Solomon Island bird species reveal differing potential routes of island colonization By Jason M. Sardell Abstract Species assemblages on islands are products of colonization and extinction events, with traditional models of island biogeography emphasizing build-up of biodiversity on small islands via colonizations from continents or other large landmasses. However, recent phylogenetic studies suggest that islands can also act as sources of biodiversity, but few such “upstream” colonizations have been directly observed. In this paper, I report four putative examples of recent range expansions among the avifauna of Makira and its satellite islands in the Solomon Islands, a region that has recently been subject to extensive anthropogenic habitat disturbance. They include three separate examples of inter-island dispersal, involving Geoffroyus heteroclitus, Cinnyris jugularis, and Rhipidura rufifrons, which together represent three distinct possible patterns of colonization, and one example of probable downslope altitudinal range expansion in Petroica multicolor. Because each of these species is easily detected when present, and because associated localities were visited by several previous expeditions, these records likely represent recent dispersal events rather than previously-overlooked rare taxa. As such, these observations demonstrate that both large landmasses and small islands can act as sources of island biodiversity, while also providing insights into the potential for habitat alteration to facilitate colonizations and range expansions in island systems. Author E-mail: [email protected] Pacific Science, vol. 70, no. 2 December 16, 2015 (Early view) Introduction The hypothesis that species assemblages on islands are dynamic, with inter-island dispersal playing an important role in determining local community composition, is fundamental to the theory of island biogeography (MacArthur and Wilson 1967, Losos and Ricklefs 2009). -

The Naturalist and His 'Beautiful Islands'

The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lawrence, David (David Russell), author. Title: The naturalist and his ‘beautiful islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific / David Russell Lawrence. ISBN: 9781925022032 (paperback) 9781925022025 (ebook) Subjects: Woodford, C. M., 1852-1927. Great Britain. Colonial Office--Officials and employees--Biography. Ethnology--Solomon Islands. Natural history--Solomon Islands. Colonial administrators--Solomon Islands--Biography. Solomon Islands--Description and travel. Dewey Number: 577.099593 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: Woodford and men at Aola on return from Natalava (PMBPhoto56-021; Woodford 1890: 144). Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgments . xi Note on the text . xiii Introduction . 1 1 . Charles Morris Woodford: Early life and education . 9 2. Pacific journeys . 25 3 . Commerce, trade and labour . 35 4 . A naturalist in the Solomon Islands . 63 5 . Liberalism, Imperialism and colonial expansion . 139 6 . The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital . 169 7 . Expansion of the Protectorate 1898–1900 . -

Pacific Islands Herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 11 Article 1 Number 3 – Number 4 12-29-1951 Pacific slI ands herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A check list of species Vasco M. Tanner Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Vasco M. (1951) "Pacific slI ands herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A check list of species," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 11 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol11/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. U8fW Ul 22 195; The Gregft fiasib IfJaturalist Published by the Department of Zoology and Entomology Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Volume XI DECEMBER 29, 1951 Nos. III-IV PACIFIC ISLANDS HERPETOLOGY, NO. V GUADALCANAL, SOLOMON ISLANDS: l A CHECK LIST OF SPECIES ( ) VASCO M. TANNER Professor of Zoology and Entomology Brigham Young University Provo, Utah INTRODUCTION This paper, the fifth in the series, deals with the amphibians and reptiles, collected by United States Military personnel while they were stationed on several of the Solomon Islands. These islands, which were under the British Protectorate at the out-break of the Japanese War in 1941, extend for about 800 miles in a southeast direction from the Bismarck Archipelago. They lie south of the equator, between 5° 24' and 10° 10' south longitude and 154° 38' and 161° 20' east longitude, which is well within the tropical zone. -

Another New Member of the Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) Indicus Group (Sauria, Varanidae): an Undescribed Species from Rennen Island, Solomon Islands

Another new member of the Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) indicus group (Sauria, Varanidae): an undescribed species from Rennen Island, Solomon Islands WOLFGANG BöHME, KAI PHILIPP & THOMAS ZIEGLER Abstract A new species ofbig-growing monitor lizard is described from Rennell Island, Solomon Islands. lt is a member of the Varanus indicus group within the subgenus Euprepiosaurus FITZINGER and is distinguished from all other representatives ofthis group by the combination of several scalation characters, colour pattern, and hemipenial characters. Above all, the new species is characterized by a weakly compressed tail being roundish in its proximal third where it lacks a double-crested mediankeel. Key words: Sauria: Varanidae: Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) indicus group; new species; Solomon Islands: Rennell Island. Zusammenfassung Ein weiteres neues Mitglied der Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) indicus-Gruppe ( Sauria: Varanidae ): Eine unbeschriebene Art von der Insel Rennell, Salomonen . ' Wir beschreiben eine neue, großwüchsige Waranart von der zu den Salomonen gehörenden, weit abseits im südöstlichen Pazifik liegenden Rennell-Insel, deren Belegexemplare aus dem Zoologi schen Museum der Universität Kopenhagen bereits 1962 während der Noona-Dan-Schiffs expedition gesammelt worden waren. Die neue Art gehört - innerhalb der Untergattung Eupre piosaurus FnZTNGER - zur Varanus indicus-Gruppe und unterscheidet sich von allen neun bisher bekannten Arten dieser Gruppe (V. caerulivirens, V. cerambonensis, V. doreanus, V. finschi, V. indicus, V. jobiensis, V. melinus, V. spinulosus und V. yuwonoi) durch die Kombination folgender Merkmale: Fehlende Blaufärbung; Schwanz ungebändert; kein Schläfen band; helle, ungezeichnete Kehlregion; retikulierte bis ozellierte Bauchzeichnung beim Jungtier; helle, nur im Vorderbereich undeutlich pigmentierte Zunge; Hemipenis mit nur an einer Seite ausgebildeten, sich zum äußeren der beiden apikalen Loben erstreckenden Paryphasmata. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

RUSI of NSW Paper

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article USI Vol63 No2 Jun12:USI Vol55 No4/2005 8/06/12 10:01 AM Page 25 INSTITUTE PROCEEDINGS JFK in the Pacific: PT-109 a presentation to the Institute on 30 January 2011 by Lieutenant Colonel Owen OʼBrien (Retʼd) John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States, served in the United States Naval Reserve in the Pacific in World War II. A motor torpedo patrol boat he commanded, PT-109, collided with a Japanese destroyer and sank in the Solomon Islands. Here, Owen OʼBrien describes these events, drawing on recently-released documents from the United States archives. Key words: John F. Kennedy; PT-109; World War II; Pacific Theatre; Solomon Islands; patrol boats; PT boats. Despite being an infantryman, I wish to tell you furniture, and car, and Major-General Sutherland’s about brave sailors, famous men, political spin, and Cadillac, and gold from the Philippines President, he giant egos – the stuff of legend! Tales of John Fitzgerald had to fly to Alice Springs in the centre of Australia, and Kennedy (JFK – or ‘Jack’ as he was known to family and then get a train to Adelaide in the south. -

Patience of Solomons

Cruising Helmsman September 2019 12 PACIFIC Patience of DESTINATION Solomons FIRST IMPRESSIONS CAN BE DIFFICULT TO COUNTER, SOMETIMES IT TAKES TIME AND EXPERIENCE. HEATHER FRANCIS I TRY not to be swayed by first impressions. A local woman called out across the path, I like to give myself a week or two before I frothy spittle and bits of masticated bark spilling really make up my mind about a place. from her mouth as she spoke in broken English. By then, the thrill of arriving has worn off and Her eyes were wide and wired, like someone who the reality of our surroundings has had a chance has had ten too many cups of coffee. Her teeth, to sink in. However, some places make more the ones she had left, were the colour of rust. of an impression than most. The small town of I could neither smile nor look away. My Lata on Ndende island, our first landfall in the camera was at my hip, but reaching for it seemed Solomon’s, was one of those places. intrusive and, maybe, a little dangerous. Approaching the beach in our dinghy I was I would discover that chewing betel nut is both a surprised to see that the high tide line was not national past time and a national health problem. a collection of plastic bags and left thongs, as It was a habit that we would see throughout our ten is the norm these days. Instead it was a wall of month stay in the Solomon Islands, although rarely crushed soft drink cans, each one sharper than quite as vivid, or disgusting, as this first contact. -

Victory in the Pacific Battle of Guadalcanal

• War in the Pacific Series • Bringing history to life Victory in the Pacific Battle of Guadalcanal Brisbane • Guadalcanal • Tulagi August 1–9, 2022 Featuring world-renowned naval historian and author James D. Hornfischer Book early and save! Visit ww2museumtours.org for details. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM I am honored to join The National WWII Museum on this tour of Guadalcanal, EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL PROGRAM the target of the first major Allied offensive of World War II. With its position in the South Pacific, Guadalcanal was an ideal location for a Japanese airfield that could threaten vital US sea lanes to Australia. Seeing the threat, the American high command resolved at once that the airfield must never become operational. On August 7, 1942, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift’s First Marine Division carried out the first American amphibious invasion of the war, with barely a shot being fired. As we will see on the tour, the anticlimax of the landings suggested none of the hell that lay ahead. Subjected to fierce counterattacks and suicidal charges by Japanese soldiers, the Marines on Guadalcanal fought tenaciously. Traversing the terrain of Bloody Ridge, standing on the banks of the Tenaru River, and investigating the jungle terrain, we will gain a renewed appreciation for what our men achieved. Meanwhile, in the narrow straits of the Slot, the US Navy began a death match against the Japanese fleet to defend the Marine lodgment. As I wrote in my book Travel to Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal, the four nighttime surface actions fought in the waters off Guadalcanal claimed the lives of three sailors for every man who died in battle ashore. -

Island NZ 16 Feb 2017

© Klaus Obermeyer Village4 islandtimeKids, Sasavele © January/FebruaryKlaus Obermeyer 2018 @ Dive Munda Media Solomon Islands Dive Festival Islandtime senior writer Scott Lee visits the Solomon Islands to experience the second annual Solomon Islands Dive Festival. Museum @ www.adambeardphotography.com January/February 2018 islandtime 5 WWII Museum @ www.adambeardphotography.com Taka @ www.adambeardphotography.com As an avid diver with years of experience diving in the tropics Scott was amazed at the plethora of adventures available in the relatively unexplored, untouched paradise. Organised to showcase the magnificent diving opportunities available in the Solomons hurry and the numerous stray dogs only moved to reposition themselves in the shade. Our western province, the festival included three days at Gizo, two days on the live-aboard dive hotel, the Gizo Hotel, was directly opposite the seawall offering an excellent vantage point to boat Taka, and a couple of days at Munda. watch the comings and goings. A comfortable three-star property, the Gizo Hotel has a large restaurant built in the traditional style overlooking the action. Complete with swimming pool Festival attendees had the opportunity to experience some of the top diving sites available and private outdoor seating area it’s the ideal base when staying in Gizo. and learn the history and culture of these magic islands. While the Solomons are famous for the Second World War ship and plane wreck dives, the pristine reefs and abundance of sea life make this a very attractive diving destination – and Dive Gizo we got to experience a bit of everything during our week. Danny and Kerrie started Dive Gizo in 1985 so they have had plenty of time to suss out the Another benefit of spending a week at the festival with a group of passionate diving best dives and there is certainly plenty to see.