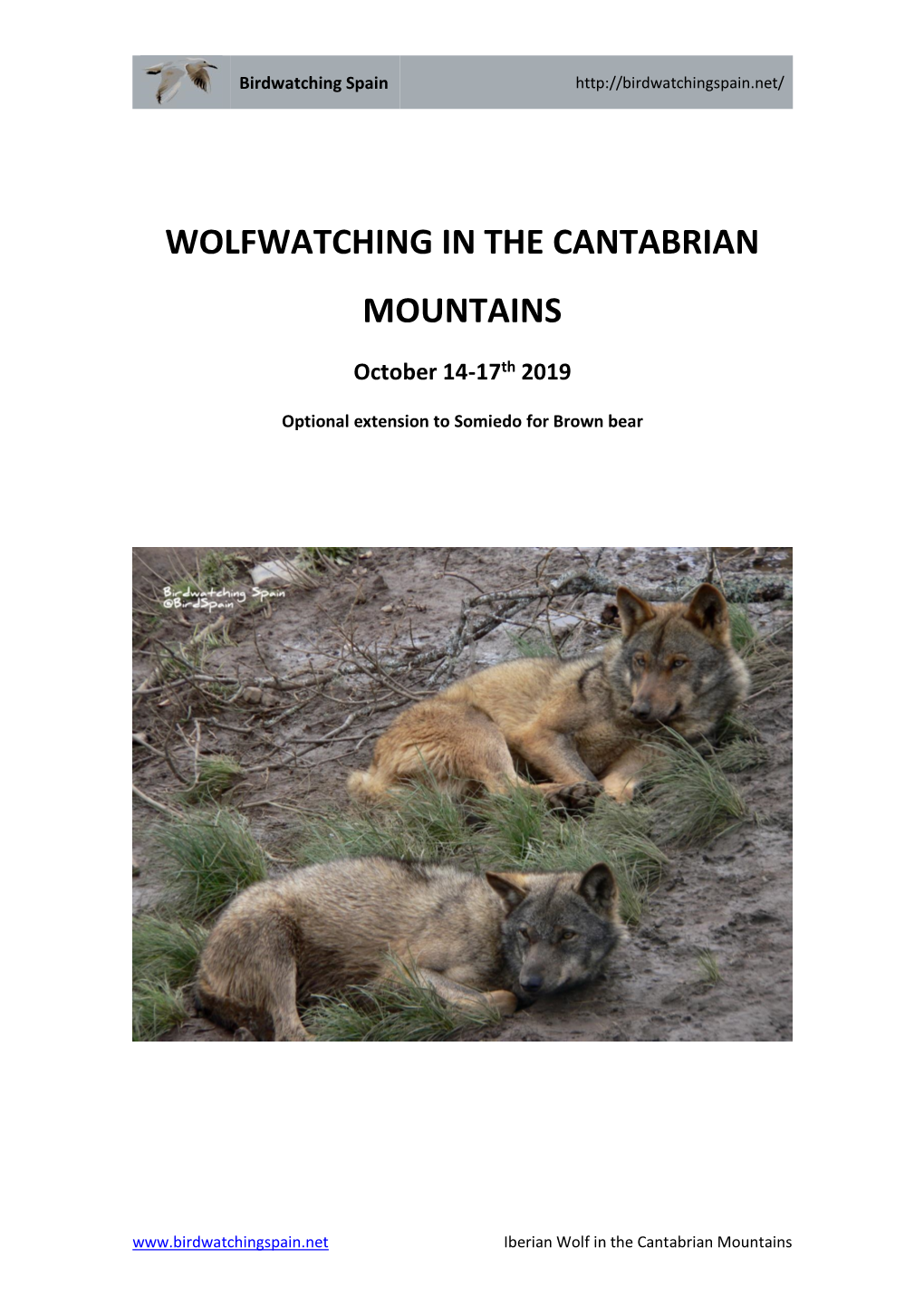

Wolfwatching in the Cantabrian Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asturica Augusta

Today, as yesterday, communication and mobility are essential in the configuration of landscapes, understood as cultural creations. The dense networks of roads that nowadays crisscross Europe have a historical depth whose roots lie in its ancient roads. Under the might of Rome, a network of roads was designed for the first time that was capable of linking points very far apart and of organizing the lands they traversed. They represent some of the Empire’s landscapes and are testimony to the ways in which highly diverse regions were integrated under one single power: Integration Water and land: Integration Roads of conquest The rural world of the limits ports and trade of the mountains Roads of conquest The initial course of the roads was often marked by the Rome army in its advance. Their role as an instrument of control over conquered lands was a constant, with soldiers, orders, magistrates, embassies and emperors all moving along them. Alesia is undoubtedly one of the most emblematic landscapes of the war waged by Rome’s legions against the peoples that inhabited Europe. Its material remains and the famous account by Caesar, the Gallic Wars, have meant that Alesia has been recognized for two centuries now as a symbol of the expansion of Rome and the resistance of local communities. Alesia is the famous battle between Julius Caesar and Vercingetorix, the Roman army against the Gaulish tribes. The siege of Alesia took place in 52 BC, but its location was not actually discovered until the 19th century thanks to archeological research! Located on the site of the battle itself, in the centre of France, in Burgundy, in the village of Alise-Sainte-Reine, the MuseoParc Alesia opened its doors in 2012 in order to provide the key to understanding this historical event and the historical context, in order to make history accessible to the greatest number of people. -

Skeletonized Microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian Transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, Northern Spain

Skeletonized microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain SÉBASTIEN CLAUSEN and J. JAVIER ÁLVARO Clausen, S. and Álvaro, J.J. 2006. Skeletonized microfossils from the Lower–Middle Cambrian transition of the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (2): 223–238. Two different assemblages of skeletonized microfossils are recorded in bioclastic shoals that cross the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary in the Esla nappe, Cantabrian Mountains. The uppermost Lower Cambrian sedimentary rocks repre− sent a ramp with ooid−bioclastic shoals that allowed development of protected archaeocyathan−microbial reefs. The shoals yield abundant debris of tube−shelled microfossils, such as hyoliths and hyolithelminths (Torellella), and trilobites. The overlying erosive unconformity marks the disappearance of archaeocyaths and the Iberian Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary. A different assemblage occurs in the overlying glauconitic limestone associated with development of widespread low−relief bioclastic shoals. Their lowermost part is rich in hyoliths, hexactinellid, and heteractinid sponge spicules (Eiffelia), chancelloriid sclerites (at least six form species of Allonnia, Archiasterella, and Chancelloria), cambroclaves (Parazhijinites), probable eoconchariids (Cantabria labyrinthica gen. et sp. nov.), sclerites of uncertain af− finity (Holoplicatella margarita gen. et sp. nov.), echinoderm ossicles and trilobites. Although both bioclastic shoal com− plexes represent similar high−energy conditions, the unconformity at the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary marks a drastic replacement of microfossil assemblages. This change may represent a real community replacement from hyolithelminth−phosphatic tubular shells to CES (chancelloriid−echinoderm−sponge) meadows. This replacement coin− cides with the immigration event based on trilobites previously reported across the boundary, although the partial infor− mation available from originally carbonate skeletons is also affected by taphonomic bias. -

Evaluation of the State of Nature Conservation in Spain October 2008

Evaluation of the state of nature conservation in Spain October 2008 Report of Sumario 3 Introduction 5 Regulatory and administrative management framework 9 Protection of species 13 Protection of natural sites 19 New threats 23 Conclusions and proposals Área de Conservación de la Naturaleza Ecologistas en Acción Marqués de Leganés, 12 - 28004 Madrid Phone: +34 915312389, Fax: +34 915312611 [email protected] www.ecologistasenaccion.org Translated by Germaine Spoerri, Barbara Sweeney, José H. Wilson, Teresa Dell and Adrián Artacho, from Red de Traductoras/es en Acción Introduction pain is known and appreciated worldwide for its natural abundance. Its favourable biogeographical position, variety of climate and orography, extensive coastline and significant Sgroups of islands confer Spain with extraordinary natural conditions. The great diversity of ecosystems, natural areas and wild species native to Spain make it the country with the greatest biodiversity in Europe and a point of reference on the issue of nature conservation. Figures released by the Spanish Ministry of the Environment are revelatory in this regard. The total estimated number of taxons in Spain exceeds 100.000. It is the country with the highest number of endangered vascular plants in the European Community and 26% of its vertebrates are included in the “endangered”, “vulnerable” or “rare” categories, according to classification of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). A clear example of the importance of biodiversity in Spain is the identification of more than 121 types of habitats, which represent more than 65% of habitat types listed in the European Directive 92/34 and more than 50% of habitats considered priority by the Council of Europe. -

The Trophic Ecology of Wolves and Their Predatory Role in Ungulate Communities of Forest Ecosystems in Europe

Acta Theriologica 40 (4): 335-386,1095, REVIEW PL ISSN 0001-7051 The trophic ecology of wolves and their predatory role in ungulate communities of forest ecosystems in Europe Henryk OKARMA Okarma H. 1995. The trophic ecology of wolves and their predatory role in ungulate communities of forest ecosystems in Europe. Acta Theriologica 40: 335-386. Predation by wolves Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758 in ungulate communities in Europe, with special reference to the multi-species system of Białowieża Primeval Forest (Poland/Belarus), was assessed on the basis results of original research and literature. In historical times (post-glacial period), the geographical range of the wolf and most ungulate species in Europe decreased considerably. Community richness of ungulates and potential prey for wolves, decreased over most of the continent from 5-6 species to 2-3 species. The wolf is typically an opportunistic predator with a highly diverse diet; however, cervids are its preferred prey. Red deer Ceruus elaphus are positively selected from ungulate communities in all localities, moose Alces alces are the major prey only where middle-sized species are scarce. Roe deer Capreolus capreolus are locally preyed on intensively, especially where they have high density, co-exist mainly with moose or wild boar Sus scrofa, and red deer is scarce or absent. Wild boar are generally avoided, except in a few locations; and European bison Bison bonasus are not preyed upon by wolves. Wolf predation contributes substantially to the total natural mortality of ungulates in Europe: 42.5% for red deer, 34.5% for moose, 25.7% for roe der, and only 16% for wild boar. -

Iberian Wolf and Tourism in the “Emptied Rural Spain”

TERRA. Revista de Desarrollo Local e-ISSN: 2386-9968 Número 6 (2020), 179-203 DOI 10.7203/terra.6.16822 IIDL – Instituto Interuniversitario de Desarrollo Local Iberian Wolf and tourism in the “Emptied Rural Spain” Pablo Lora Bravo Estudiante de Máster en Dirección y Planificación del Turismo. Universidad de Sevilla (Sevilla, España) [email protected] Arsenio Villar Lama Prof. Contratado Dr. Dpto. De Geografía Física y Análisis Geográfico Regional. Universidad de Sevilla (Sevilla, España) [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3840-4399 Esta obra se distribuye con la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional ARTICLE SECTION Iberian Wolf and tourism in the “Emptied Rural Spain” Abstract: The present study analyzes the tourist activity of observation of the Iberian wolf in Spain as an alternative to other traditional tourist modalities in rural areas. The own experience within the sector has been crucial to understand its dynamics and develop this work. It studies the upward trend of nature tourism in general and the observation of the Iberian wolf in particular, the modus operandi of the activity is described and its main impacts are exposed. Wolf tourism generally provides benefits for the local population in economic, environmental and socio-cultural terms. Its compatibility with the environment and the intrinsic characteristics of the activity closely linked to a sustainable, fresh and offline tourism turns this sector into an interesting tool to mitigate the demographic, economic and social emptying of some areas of Spain. Key words: Iberian wolf, wildlife tourism, environmental education, local development, territorial intelligence, Spain. Recibido: 12 de marzo de 2020 Devuelto para revisión: 9 de abril de 2020 Aceptado: 22 de abril de 2020 Citation: Lora, P., y Villar, A. -

Connectivity Study in Northwest Spain: Barriers, Impedances, and Corridors

sustainability Article Connectivity Study in Northwest Spain: Barriers, Impedances, and Corridors Enrique Valero, Xana Álvarez * and Juan Picos AF4 Research Group, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Engineering, Forestry Engineering College, University of Vigo, Campus A Xunqueira, s/n, 36005 Pontevedra, Spain; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (J.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-986-801-959 Received: 9 August 2019; Accepted: 14 September 2019; Published: 19 September 2019 Abstract: Functional connectivity between habitats is a fundamental quality for species dispersal and genetic exchange throughout their distribution range. Brown bear populations in Northwest Spain comprise around 200 individuals separated into two sub-populations that are very difficult to connect. We analysed the fragmentation and connectivity for the Ancares-Courel Site of Community Importance (SCI) and its surroundings, including the distribution area for this species within Asturias and in the northwest of Castile and León. The work analysed the territory’s connectivity by using Geographic Information Systems (GIS). The distance-cost method was used to calculate the least-cost paths with Patch Matrix. The Conefor Sensinode software calculated the Integral Connectivity Index and the Connectivity Probability. Locating the least-cost paths made it possible to define areas of favourable connectivity and to identify critical areas, while the results obtained from the connectivity indices led to the discovery of habitat patches that are fundamental for maintaining connectivity within and between different spaces. Three routes turned out to be the main ones connecting the northern (Ancares) and southern (Courel) areas of the SCI. Finally, this work shows the importance of conserving natural habitats and the biology, migration, and genetic exchange of sensitive species. -

Iberian Forests

IBERIAN FORESTS STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS OF THE MAIN FORESTS IN THE IBERIAN PENINSULA PABLO J. HIDALGO MATERIALES PARA LA DOCENCIA [144] 2015 © Universidad de Huelva Servicio de Publicaciones © Los Autores Maquetación BONANZA SISTEMAS DIGITALES S.L. Impresión BONANZA SISTEMAS DIGITALES S.L. I.S.B.N. 978-84-16061-51-8 IBERIAN FORESTS. PABLO J. HIDALGO 3 INDEX 1. Physical Geography of the Iberian Peninsula ............................................................. 5 2. Temperate forest (Atlantic forest) ................................................................................ 9 3. Riparian forest ............................................................................................................. 15 4. Mediterranean forest ................................................................................................... 17 5. High mountain forest ................................................................................................... 23 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 27 Annex I. Iberian Forest Species ...................................................................................... 29 IBERIAN FORESTS. PABLO J. HIDALGO 5 1. PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE IBERIAN PENINSULA. 1.1. Topography: Many different mountain ranges at high altitudes. Two plateaus 800–1100 m a.s.l. By contrast, many areas in Europe are plains with the exception of several mountain ran- ges such as the Alps, Urals, Balkans, Apennines, Carpathians, -

Potential Range and Corridors for Brown Bears

POTENTIALRANGE AND CORRIDORSFOR BROWNBEARS INTHE EASTERN ALPS, ITALY LUIGIBOITANI, Department of Animaland HumanBiology, Viale Universita 32,00185-Roma, Italy,email: boitani @ pan.bio.uniromal .it PAOLOCIUCCI, Department of Animaland HumanBiology, Viale Universita 32,00185-Roma, Italy,email: ciucci@ pan.bio.uniromal .it FABIOCORSI, Istituto Ecologia Applicata, Via Spallanzani 32,00161 -Roma,Italy, email: corsi @ pan.bio.uniromal .it EUGENIODUPRE', Istituto Nazionale Fauna Selvatica, Via Ca Fornacetta,40064-Ozzano Emilia, Italy, email: infseuge@ iperbole.bologna.it Abstract: Although several techniqueshave been used to explore the spatialfeatures of brownbear (Ursus arctos) range (e.g., potentialdistribution ranges,linkages between isolated sub-populations, and analyses of habitatsuitability), quality and quantity of datahave often constrainedthe usefulness of the results.We used 12 environmentalvariables to identifypotentially suitable areas for bears in the Italianpart of the EasternAlps. We usedMahalanobis distancestatistic as a relativeindex of the environmentalquality of the studyarea by calculatingfor eachpixel (250 meters)the distancefrom the centroid of the environmentalconditions of 100 locationsrandomly selected within known bear ranges. We used differentlevels of this suitabilityindex to identify potentialoptimal and sub-optimal areas and their interconnecting corridors. The model identified4 majorareas of potentialbear presence having a total size of about 10,850 km2.Assuming functionalconnectivity among the areasand mean density -

Iberian Wolf (Canis Lupus Signatus) in Relation to Land Cover, Livestock and Human Influence in Portugal

Mammalian Biology 76 (2011) 217–221 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Mammalian Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.de/mambio Original Investigation Presence of Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) in relation to land cover, livestock and human influence in Portugal Julia Eggermann a,∗, Gonc¸ alo Ferrão da Costa b, Ana M. Guerra b, Wolfgang H. Kirchner a, Francisco Petrucci-Fonseca b,c a Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Ruhr University Bochum, Universitätsstraße 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany b Grupo Lobo, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Bloco C2, 3◦Piso, Departamento de Biologia Animal, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal c Centro de Biologia Ambiental, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal article info abstract Article history: From June 2005 to March 2007, we investigated wolf presence in an area of 1000 km2 in central north- Received 19 August 2009 ern Portugal by scat surveys along line transects. We aimed at predicting wolf presence by developing Accepted 30 October 2010 a habitat model using land cover classes, livestock density and human influence (e.g. population and road density). We confirmed the presence of three wolf packs by kernel density distribution analysis of Keywords: scat location data and detected their rendezvous sites by howling simulations. Wolf habitats were char- Canis lupus signatus acterized by lower human presence and higher densities of livestock. The model, developed by binary Habitat utilization analysis logistic regression, included the variables livestock and road density and correctly predicted 90.7% of Human influence Logistic regression model areas with wolf presence. Wolves avoided the closer surroundings of villages and roads, as well as the Portugal general proximity to major roads. -

Asturias (Northern Spain) As Case Study

Celts, Collective Identity and Archaeological Responsibility: Asturias (Northern Spain) as case study David González Álvarez, Carlos Marín Suárez Abstract Celtism was introduced in Asturias (Northern Spain) as a source of identity in the 19th century by the bourgeois and intellectual elite which developed the Asturianism and a regionalist political agenda. The archaeological Celts did not appear until Franco dictatorship, when they were linked to the Iron Age hillforts. Since the beginning of Spanish democracy, in 1978, most of the archaeologists who have been working on Asturian Iron Age have omit- ted ethnic studies. Today, almost nobody speaks about Celts in Academia. But, in the last years the Celtism has widespread on Asturian society. Celts are a very important political reference point in the new frame of Autonomous regions in Spain. In this context, archaeologists must to assume our responsibility in order of clarifying the uses and abuses of Celtism as a historiographical myth. We have to transmit the deconstruction of Celtism to society and we should be able to present alternatives to these archaeological old discourses in which Celtism entail the assumption of an ethnocentric, hierarchical and androcentric view of the past. Zusammenfassung Der Keltizismus wurde in Asturien (Nordspanien) als identitätsstiftende Ressource im 19. Jahrhundert durch bürgerliche und intellektuelle Eliten entwickelt, die Asturianismus und regionalistische politische Ziele propagierte. Die archäologischen Kelten erschienen allerdings erst während der Franco-Diktatur, während der sie mit den eisen- zeitlichen befestigten Höhensiedlungen verknüpft wurden. Seit der Einführung der Demokratie in Spanien im Jahr 1978 haben die meisten Archäologen, die über die asturische Eisenzeit arbeiten, ethnische Studien vernachlässigt. -

Connecting the Iberian Wolf in Portugal - Project Lobo Na Raia

The Newsletter of The Wolves and Humans Foundation No. 28, Spring 2013 Connecting the Iberian wolf in Portugal - Project Lobo na Raia Iberian wolf caught by camera trap during monitoring Photo: Grupo Lobo/Zoo Logical he Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus), south of the River Douro can act as a bridge once a common species along the between these population clusters. TPortuguese border in the region south of the River Douro, has been gradually disappearing since The goals of the Lobo na Raia project are: to the 1970s. Direct persecution, habitat loss and loss identify wolf presence in the study area; assess the of wild prey caused a drastic reduction in numbers, applicability of different non-invasive methods of approaching the threshold of local extinction. population monitoring; identify the main threats to Recent population monitoring studies have wolves in the region, and apply direct and confirmed the current precarious status of the wolf, secondary conservation measures to promote with continued persecution, disturbance and population recovery. dwindling prey remaining significant threats. The border region south of the River Douro is Genetic data has confirmed the barrier effect of the typically Mediterranean, including and abundance River Douro, which isolates two distinct wolf of flora species such as holm Oak (Quercus ilex), nuclei: a stable population in the north, and a and gum rockrose (Cistus ladanifer), and vulnerable and isolated population in the south. emblematic endangered fauna including the Connectivity between different population groups Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) and the is therefore essential to recover fragmented wolf black stork (Ciconia nigra). This semi-wild region populations and to ensure their long term viability. -

European Grey Wolf (Canis Lupus)

Rev. 22 July 2021 European Grey Wolf (Canis lupus) Photo © MrT HK IMPACTS OF TROPHY HUNTING QUICK FACTS: • Unsustainable offtake Population Europe: 17,000; EU: 13,000-14,000 • Social disruption Size: (2018) • Increases human-wolf conflict Population Europe: Increasing; EU: Unknown • Ineffective at preventing livestock loss Trend: (2018) Range: Unknown IUCN Red Least Concern in Europe and EU POPULATION List: (2018) CITES: Appendix II (since 2010) The grey wolf (Canis lupus) is found in Europe, Asia, and North America. The broader European popu- International 73 trophies exported from the EU lation is estimated to exceed 17,000 wolves and in- Trade: from 2009-2018 (69 originated in EU) creasing as of 2018.1 The European Union (EU) pop- ulation is estimated at fewer than 13,000-14,000 Threats: Human intolerance, poorly regulat- wolves across all EU Member States as of 2018.1 ed hunting, poaching, poor species management The grey wolf is considered Least Concern at glob- al, European, and EU levels.1 Within Europe, there are nine populations, each with its own IUCN status (see Table 1 below). There was a tenth population, insula is a distinct subspecies (Canis lupus italicus). Sierra Morena in Spain, which has been extirpated. The Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) may also be In addition, the wolf population on the Italian pen- a distinct subspecies.1 Table 1. European population summary (IUCN).1,2 Population Countries Population size (mature Population IUCN status individuals) trend (2018) Baltic Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland 1,713–2,240