Di Cesnola Sample.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'accent De La Province

L’Accent de la province Marc Aymes To cite this version: Marc Aymes. L’Accent de la province : Une histoire des réformes ottomanes à Chypre au XIXe siècle. Histoire. Université Aix-Marseille 1, 2005. Français. tel-01345139 HAL Id: tel-01345139 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01345139 Submitted on 13 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ AIX-MARSEILLE I (UNIVERSITÉ DE PROVENCE) U.F.R. Civilisations et humanités École doctorale « Espaces, cultures, sociétés » Marc AYMES L’Accent de la province UNE HISTOIRE DES RÉFORMES OTTOMANES À CHYPRE AU XIXe SIÈCLE Volume I Thèse en vue de l’obtention du doctorat d’histoire soutenue le 10 décembre 2005 Jury : M. Michel BALIVET, Université Aix-Marseille 1 Mme Leila FAWAZ, Tufts University M. François GEORGEON, CNRS M. Robert ILBERT, Université Aix-Marseille 1 (directeur) M. Eugene ROGAN, Oxford University Avant-propos C’est un souvenir enfoui. Un legs indû, un don sans lignée ni retour possibles. C’est l’histoire d’un monde révolu dont je ne suis pas, mais dois répondre. -

Luigi Palma Di Cesnola Collection, 1861-1950S (Bulk, 1861-1904)

Luigi Palma di Cesnola collection, 1861-1950s (bulk, 1861-1904) Finding aid prepared by Celia Hartmann Processing of this collection was funded by a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on May 18, 2015 The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028-0198 212-570-3937 [email protected] Luigi Palma di Cesnola collection, 1861-1950s (bulk, 1861-1904) Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical note.................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note.....................................................................................................5 Arrangement note................................................................................................................ 5 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 6 Related Materials .............................................................................................................. 6 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory............................................................................................................8 Series I. Museum Administration................................................................................ -

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from The Library of Congress http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog36newy THE NEW YORK Genealogical and Biographical Reqord. DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XXXVI, 1905. PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, 226 West 58TH Street, New York. p Publication Committee : Rev. MELATIAH EVERETT DWIGHT, Editor. Dr. HENRY R. STILES. H. CALKINS. JR. TOBIAS A. WRIGHT. —— — INDEX OF SUBJECTS. — Accessions to the Library, 80, 161, 239, Book Notices (continued) 320 Collections of the N. Y. Historical Amenia, N. Y., Church Records, 15 Soc. for 1897, 315 American Revolution, Loyalists of, see Connecticut Magazine, Vol. IX, New Brunswick No. 3, 316. Ancestry of Garret Clopper, The, 138 Cummings Memorial, 235 Authors and Contributors De Riemer Family, The, 161 Botsford, H. G.. 138 Devon and Cornwall Record Soc. Brainard, H. W., 33, 53, 97 (Part 0,235 Clearwater, A. T., 245 Dexter Genealogy, 159 of De Riemer, W. E., 5 Digest Early Conn. Probate De Vinne, Theo. L., I Records, Vol. II, 161 Dwight, Rev. M. E., 15 Documents Relating to the Colon- Fitch, Winchester, 118, 207, 302 ial History of New Jersey, Vol. Griffen, Zeno T., 197, 276 XXIII, 73 Hance, Rev. Wm. W, 17, 102, 220 Eagle's History of Poughkeepsie, Harris Edward D., 279 The, 318 Hill, Edward A., 213, 291 Family of Rev. Solomon Mead, Horton, B. B., 38, 104 159 Jack, D. R., 27, 185, 286 Forman Genealogy, 160 Jones, E. S., 38, 104 Genealogical and Biographical Morrison, Geo. -

The Aegean and Cyprus

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, page 312-335 15 The Aegean and Cyprus Yannis Galanakis and Dan Hicks 15.1 Introduction The Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) holds c. 480 objects from the Aegean (Greek mainland, Crete and the Cyclades) and c. 292 objects from Cyprus that are currently defined as archaeological. This chapter provides an overview of this material, and also considers the 25 later prehistoric archaeological objects from Turkey that are held in the Museum (Figure 15.1). The objects range chronologically from the later prehistoric (Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age) to the medieval period. Falling outside of the geographical scope of this chapter, elsewhere this volume considers Classical Greek and Roman material from Egypt (Chapter 7) and from the Levant (Chapter 21), Neolithic and Bronze Age material from Italy (Chapter 14), and Iron Age (including Classical Greek) material from Italy (Chapter 16). The c. 797 objects considered in this chapter include material from defining excavations for the Aegean Bronze Age – Schliemann’s excavations at Troy (Hisarlık) and Mycenae, and Arthur Evans’ excavations at Knossos – as well as Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age collections from mainland Greece, Crete, the Cyclades and Cyprus. As compared with other major archaeological collections with an Aegean component, such as those of the Ashmolean Museum (Sherratt 2000),1 the later prehistoric and classical material from the Aegean and Cyprus in the PRM was collected, organised and displayed in a less explicitly art historical manner, and was often driven by Henry Balfour’s curatorial interests in technology and the PRM’s typological series. -

Cyprus: Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, and Temples

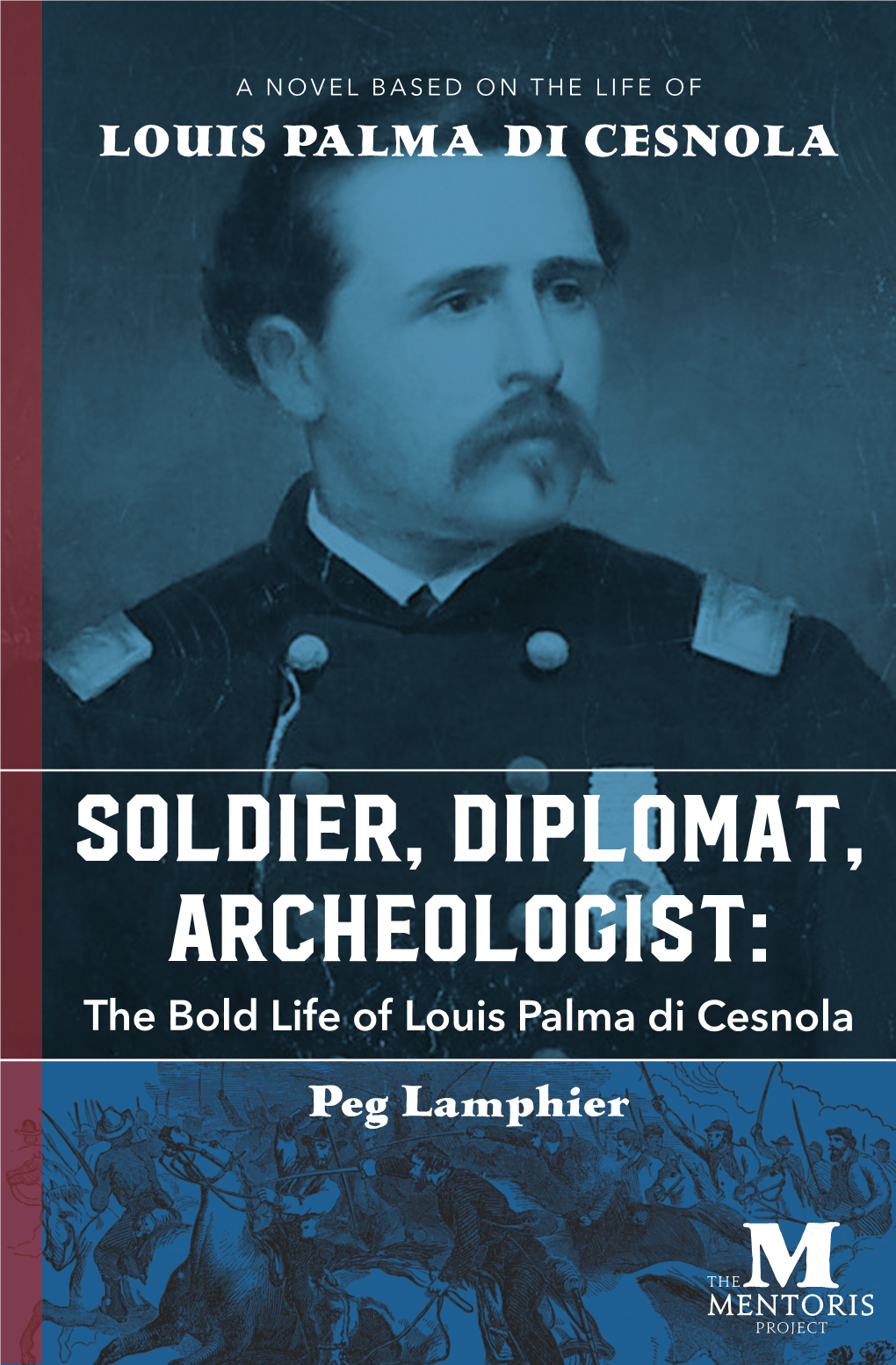

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-07861-0 - Cyprus: Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, and Temples: A Narrative of Researches and Excavations during Ten Years’ Residence Luigi Palma Di Cesnola Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE LIBRARY COLLECTION Books of enduring scholarly value Archaeology The discovery of material remains from the recent or the ancient past has always been a source of fascination, but the development of archaeology as an academic discipline which interpreted such finds is relatively recent. It was the work of Winckelmann at Pompeii in the 1760s which first revealed the potential of systematic excavation to scholars and the wider public. Pioneering figures of the nineteenth century such as Schliemann, Layard and Petrie transformed archaeology from a search for ancient artifacts, by means as crude as using gunpowder to break into a tomb, to a science which drew from a wide range of disciplines - ancient languages and literature, geology, chemistry, social history - to increase our understanding of human life and society in the remote past. Cyprus: Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, and Temples Born in Italy, Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832–1904) settled in the United States and fought for the North in the American Civil War, becoming a cavalry colonel. Appointed by Abraham Lincoln, he then served as consul to Cyprus from 1865 to 1877. As an amateur archaeologist, he directed excavations throughout the island. In this 1877 publication, including maps and illustrations, Cesnola gives a useful sketch of Cypriot history and contemporary customs in addition to providing an important record of his archaeological practices and discoveries. He covers a number of ancient settlements where significant finds were made, notably Paphos, Amathus and Kourion. -

Download File

FOUNDERS AND FUNDERS: Institutional Expansion and the Emergence of the American Cultural Capital 1840-1940 Valerie Paley Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Valerie Paley All rights reserved ABSTRACT Founders and Funders: Institutional Expansion and the Emergence of the American Cultural Capital 1840-1940 Valerie Paley The pattern of American institution building through private funding began in metropolises of all sizes soon after the nation’s founding. But by 1840, Manhattan’s geographical location and great natural harbor had made it America’s preeminent commercial and communications center and the undisputed capital of finance. Thus, as the largest and richest city in the United States, unsurprisingly, some of the most ambitious cultural institutions would rise there, and would lead the way in the creation of a distinctly American model of high culture. This dissertation describes New York City’s cultural transformation between 1840 and 1940, and focuses on three of its enduring monuments, the New York Public Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Opera. It seeks to demonstrate how trustees and financial supporters drove the foundational ideas, day-to-day operations, and self- conceptions of the organizations, even as their institutional agendas enhanced and galvanized the inherently boosterish spirit of the Empire City. Many board members were animated by the dual impulses of charity and obligation, and by their own lofty edifying ambitions for their philanthropies, their metropolis, and their country. Others also combined their cultural interests with more vain desires for social status. -

A Phoenician Inscription from Cyprus in the Cesnola Collection at the Turin University Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography

Kadmos 2016; 55(1/2): 37–48 Luca Bombardieri, Anna Cannavò A Phoenician inscription from Cyprus in the Cesnola Collection at the Turin University Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography DOI 10.1515/kadmos20160003 Abstract: A previously unpublished marble fragment from the Cesnola collec- tion at the Turin University Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography bears an incomplete Phoenician inscription, a dedication to Eshmun-Melqart considered lost since 1869 (CIS I 26). The inscription allows to interpret the object bearing the dedication as a votive stone bowl from the late Classical Phoenician sanctuary of Kition-Batsalos in Cyprus, and it provides the opportunity to retrace the history of the Cesnola collection of Cypriote antiquities at the University Museum of Turin. Keywords: Luigi Palma di Cesnola; Phoenician inscription; Kition-Batsalos; Esh- mun-Melqart; Phoenician votive stone bowl; University Museum of Turin. 1 The Cypriote collections at the University Museums in Turin. The Museum of Anatomy and the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography The events which lead to the actual composition of the Cypriote collections held at the University Museums of Anthropology and Ethnography and Anatomy in Turin are rather complex to retrace. Distinct and subsequent donations between 1870 and 1881 by Luigi Palma di Cesnola and his brother Alessandro to the Royal Article note: We are very grateful to Prof. Hartmut Matthäus and to Prof. Markus Egetmeyer for their insightful comments on an early draft of this paper. Thanks are also owed to Prof.ssa Emma Rabino Massa and Dr. Rosa Boano, Museo di Antropologia ed Etnografia, Prof. Giacomo Giaco bini and Dr. -

The Effects of Antiquarianism and Colonialism on Cultural Heritage Formation: a Study of Archaeology and Museum Collection in British Cyprus

The Effects of Antiquarianism and Colonialism on Cultural Heritage Formation: A Study of Archaeology and Museum Collection in British Cyprus By Julia Wareham An Undergraduate Honors Thesis presented to the Archaeology Major Johns Hopkins University Advised by Dr. Emily Anderson April 29, 2016 Copyright © Julia Wareham 2016. All rights reserved. Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the support of my advisor, Dr. Emily Anderson, whose guidance and insight was invaluable to my research and writing process. I am also indebted to Ami Cox and the Woodrow Wilson Undergraduate Research Fellowship Program for giving me the opportunity to carry out my research in Cyprus and London in summer 2015. The Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries Special Collections and Archives was also an indispensible resource throughout my research. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 Chapter One: Archaeological Excavations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ......................7 From Vogüé to Cesnola: the beginnings of Cypriot archaeology .......................................................... 7 Excavation -

PUCK MAGAZINE Illustration Collection, 1876-C

Puck Illustration Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Extent 1.5 linear feet Processed Sarena Deglin, 2004 Contents Centerfold, front-cover, and internal illustrations from both the American and German editions of Puck, spanning the years 1876-c.1901 Access Restrictions Unrestricted Contact Information Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Delaware Art Museum 2301 Kentmere Parkway Wilmington, DE 19806 (302) 571-9590 [email protected] Preferred Citation Puck Illustration Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Copyright Information Copyright has not been assigned to the Delaware Art Museum. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Museum as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. 1 History of Puck Puck was founded by Austrian-born cartoonist Joseph Keppler and his partners as a German-language publication in 1876. The magazine took its name from the blithe spirit of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, along with its motto: “What fools these mortals be!” Puck looked different than other magazines of the day. It employed lithography in place of wood engraving and offered three cartoons instead of the usual one. The cartoons were initially printed in black and white, but later several tints were added, and soon the magazine burst into full, eye-catching color. Puck’s first English-language edition in 1877 made it a major competitor of the already established illustrated news magazines of the day, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Keppler’s former employer, and Harper’s Weekly. -

David Bunnell Olmstead Literary Portraits Sequential Listing Page

David Bunnell Olmstead Literary Portraits Sequential listing Following is a list of items in the scrapbooks, in order of appearance. Olmstead's descriptions and annotations are given in quotation marks. For example, for the first item, Maurice Thompson, Olmstead’s notes are "Poet. Novelist. 1844-1901." While the information provided by Olmstead is always interesting, it is not always accurate. Due to difficulties in reading his handwriting and to changes over time, the names given in the list below may or may not be spelled correctly or in their modern form. Common abbreviations appearing in the list and in the scrapbooks include: Personal names: Titles, ranks, etc.: Alex., Alex'r. Alexander Arc. or Arch. Archbishop And. Andrew B. Born Ant. Anthony Bap. Baptized Arch. Archibald Bar., Bart., Bt. Baron, Baronet Benj. Benjamin Bp. Bishop Ch., Cha., Chas. Charles Cap., Cap’n Captain Ed., Edw. Edwin or Edward Col. Colonel Eliz. Elizabeth DD Doctor of Divinity Fr. Francis Ed. Editor Fr’d., Fr’c., Fred., Frederic/k Eng. England Fred’k. Geo., G. George Esq. Esquire Hen., Hen’y. Henry Fr. Frater or Father Iohannus, Ioh. John FRS Fellow of the Royal Society Jas. James Gen., Gen’l General Jn., Jno., Jon. Jonathan Gov. Governor Jos. Joseph or Josiah Hon. Honorable Mich. Michael JD Juris Doctor (law degree) Rob., Robt. Robert KBE Knight of the British Empire Sam’l. Samuel KC (or QC) King’s Counsel (or Queen’s Counsel) Th., Thos. Thomas LLD Legum Doctor (law degree) Wm., Will’m. William Maj. Major MD Doctor of Medicine MP. Member of Parliament OBE Order of the British Empire PhD.