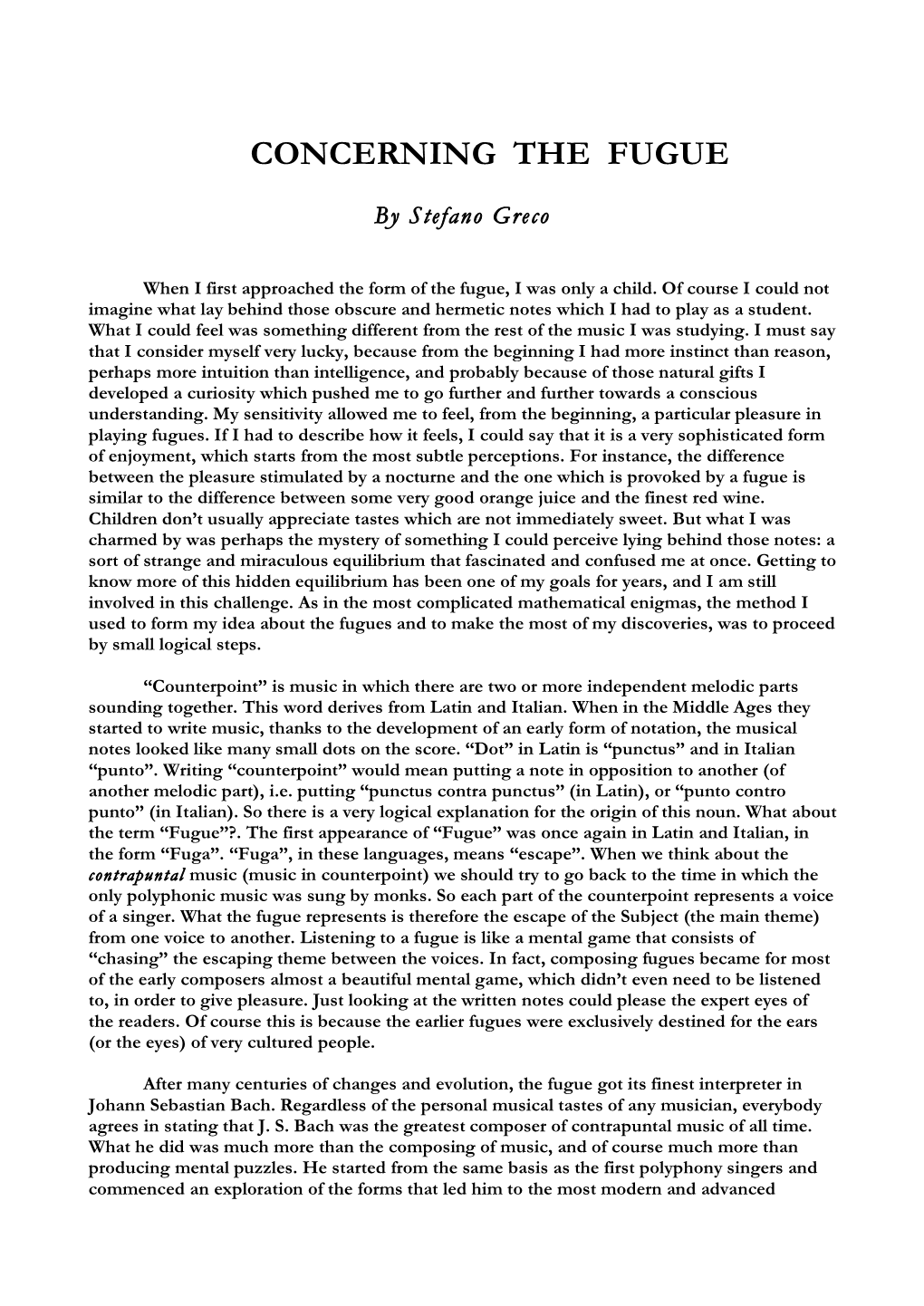

Concerning the Fugue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in JS Bach's Organ Fugues

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in J. S. Bach’s Organ Fugues BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao BFA, National Taiwan Normal University, 1999 MA, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2002 MEd, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2003 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA Abstract This study explores the musical-rhetorical tradition in German Baroque music and its connection with Johann Sebastian Bach’s fugal writing. Fugal theory according to musica poetica sources includes both contrapuntal devices and structural principles. Johann Mattheson’s dispositio model for organizing instrumental music provides an approach to comprehending the process of Baroque composition. His view on the construction of a subject also offers a way to observe a subject’s transformation in the fugal process. While fugal writing was considered the essential compositional technique for developing musical ideas in the Baroque era, a successful musical-rhetorical dispositio can shape the fugue from a simple subject into a convincing and coherent work. The analyses of the four selected fugues in this study, BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582, will provide a reading of the musical-rhetorical dispositio for an understanding of Bach’s fugal writing. ii Copyright © 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements The completion of this document would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. -

Organ Interpretation Competition for the Johann Pachelbel Award at the 69Th ION Music Festival 26 June - 02 July 2020

Organ Interpretation Competition for the Johann Pachelbel Award at the 69th ION Music Festival 26 June - 02 July 2020 A WARM INVITATION TO NUREMBERG For 52 years, young artists have been invited to come to Nuremberg in early summer to give proof of their artistic prowess to a jury comprised of prominent experts. The climax of this process has always been the presentation of the widely known Johann Pachelbel Award. And so again we issue an invitation to register for this prestigious international interpretation competition in 2020. What is it all about? The organ interpretation competition is looking for organists who in their young careers have already achieved independent interpretation of significant works of organ literature. But it will also seek interaction with contemporary works. And expect competitors to be able to deal with both the soundscapes and playing technique of historical organs and to cope with the possibilities and challenges of modern instruments. At the same time, this interpretation competition explicitly demands not only technical skills, but also looks for interpretations which are courageous, sometimes leaving matters open, finding new aspects in well-known works, and eliciting unique sounds from the instruments themselves – feeding on the tension between tradition and future perspectives. And of course, the sequence of works, the organists’ programming and sometimes the link between the individual compositions to be played is of special interest to the jurors. This is all about a contemporary way of dealing with the history of music and instruments. From the first round on, the competition will be public. The final will be an integral element of the festival programme of the 69th ION Music Festival, staged in the world famous Old Town of Nuremberg, and played on the Peter organ of St Sebaldus’ Church. -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

Fugue in C Minor the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1

chapter 2 Fugue in C Minor The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 Bach’s very best-known fugue must be the Fugue in C Minor from book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier. It has become stan- dard teaching material in advanced and elementary textbooks alike, for courses in canon and fugue as well as lowly Music Appreciation. It was the first fugue to be jazzed and the first to be switched on. Heinrich Schenker, lord and master of mod- ern music theory, settled on it as the example to expound in a classic essay, “Organicism in Fugue,” which recently pro- voked an entire critical chapter from Laurence Dreyfus in his book Bach and the Patterns of Invention. When The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians dropped Roger Bullivant’s solid article “fugue” from its second edition, what replaced it was (among other things) a blow-by-blow analysis of the Fugue in C Minor. There is a manuscript copied by one of Bach’s students con- taining analytical annotations to this work. (Some are given by David Schulenberg in The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach.) “For the use and improvement of musical youth eager to learn,” reads the 10 Fugue in C Minor / 11 title page for the WTC; did the Fugue in C Minor occupy a spe- cial place in the composer’s personal curriculum? One can even detect a mild backlash as regards the piece, as when Bullivant reaches the chapter on fugal form in his book on fugue and says he will look “not at the standard examples (WTC I C-Minor is the great favorite for an introduction to Bach’s tech- nique, WTC I C-Major being, for good reasons, beyond the understanding of the conventional theorist!) but at some of the more ‘difficult’ and, it is hoped, interesting forms.” Assuming that Bach wanted to exhibit something minimal at (or very near) the beginning of his exemplary collection of preludes and fugues, C Minor indeed presented itself as a prime candidate. -

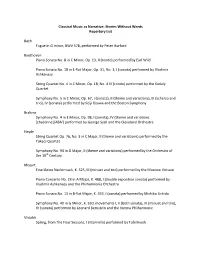

Classical'music'as'narrative

Classical'Music'as'Narrative:'Stories'Without'Words' Repertory'List' ! Bach! ! Fugue!in!G!minor,!BWV!578,!performed!by!Peter!Hurford! ! Beethoven! Piano!Sonata!No.!8!in!C!Minor,!Op.!13,!II!(rondo)!performed!by!Earl!Wild! ! Piano!Sonata!No.!18!in!ELflat!Major,!Op.!31,!No.!3,!I!(sonata)!performed!by!Vladimir! Ashkenazy! ! String!Quartet!No.!4!in!C!Minor,!Op.!18,!No.!4!IV!(rondo)!performed!by!the!Kodaly! Quartet! ! Symphony!No.!5!in!C!Minor,!Op.!67,!I!(sonata),!II!(theme!and!variations),!III!(scherzo!and! trio),!IV!(sonata)!performed!by!Seiji!Ozawa!and!the!Boston!Symphony! ! Brahms! Symphony!No.!4!in!E!Minor,!Op.!98,!I!(sonata),!IV!(theme!and!variations! [chaconne]/ABA’)!performed!by!George!Szell!and!the!Cleveland!Orchestra! ! Haydn!! String!Quartet!Op.!76,!No.!3!in!C!Major,!II!(theme!and!variations)!performed!by!the! Takacs!Quartet! ! Symphony!No.!94!in!G!Major,!II!(theme!and!variations)!performed!by!the!Orchestra!of! the!18th!Century! ! Mozart! Eine!kleine!Nachtmusik,!K.!525,!III!(minuet!and!trio)!performed!by!the!Moscow!Virtuosi! ! Piano!Concerto!No.!23!in!A!Major,!K.!488,!I!(double!exposition!sonata)!performed!by! Vladimir!Ashkenazy!and!the!Philharmonia!Orchestra! ! Piano!Sonata!No.!13!in!BLflat!Major,!K.!333,!I!(sonata)!performed!by!Michiko!Uchida! ! Symphony!No.!40!in!G!Minor,!K.!550,!movements!I,!II!(both!sonata),!III!(minuet!and!trio),! IV!(sonata)!performed!by!Leonard!Bernstein!and!the!Vienna!Philharmonic! ! Vivialdi!! Spring,!from!The!Four!Seasons,!I!(ritornello)!performed!by!Tafelmusik! ! ! ! Music'Appreciation'Texts' ! Here!are!three!good!reference!textbooks!that!cover!the!forms!and!some!of!the!pieces!we!have! studied.!All!have!accompanying!CDs,!which!are!sold!separately.!The!latest!editions!are! expensive,!but!they!are!no!better!than!the!older!editions,!which!are!not.!So!look!for!any!nonL current!edition—the!cheaper!the!better!! ! Roger!Kamien,!Music:!An!Appreciation! ! Joseph!Kerman,!Listen! ! James!Machlis,!Kristine!Forney,!The!Enjoyment!of!Music! ! ! ! ' ' ' ' ! ! ! !. -

An Exploration of Musical Form Featuring Bach's Fugue in G Minor

WHAT THE FUGUE? An exploration of musical form featuring Bach’s Fugue in G minor Presented by Alex Pierson and Logan Tolman Performance by the Caine Brass Quintet What exactly is a fugue? (fyo͞ oɡ) A fugue is a contrapuntal* composition in which a short melody or phrase (the subject) is introduced by one part and successively taken up by others and developed by interweaving the parts. *Counterpoint: The art or technique of setting, writing, or playing a melody or melodies in conjunction with another, according to fixed rules. Image credit: Crystal Broderick Counterpoint • Music that focuses on individual and independent lines of music that interplay with each other. • Focuses on musical lines rather than chords or chord progressions • Artfully moves from dissonant intervals to consonant intervals between the separate lines. Subject • The main theme • Introduced by the first voice/player • This is what will repeat and vary slightly throughout the piece Answer • A response to the subject based off of the same musical theme • May or may not use the same intervals as the theme • Always starts on a different pitch than the subject Counter Subject • A secondary theme, like the subject, that gets passed around between voices/parts and is developed throughout the piece • Usually appears when a voice is beginning an answer Episode • Sections of the piece after all the voices/parts have been introduced where no part of the subject is present • All the voices are interplaying and developing other ideas that have been presented • Alternates with Entries throughout the rest of the piece I don’t see the Subject…. -

The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach Konstantinos Alevizos

Bibliographical anachronism: The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach Konstantinos Alevizos To cite this version: Konstantinos Alevizos. Bibliographical anachronism: The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach. 2021. hal-03161248 HAL Id: hal-03161248 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03161248 Preprint submitted on 5 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Bibliographical anachronism: The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach. A. Criteria to Establish the Progression1. The Art of Fugue is a collection of compositions in an austere contrapuntal style, all of which are based on the same subject. The latest research on the score reveals that Bach started this copious work around 17422. However, it is known that the first edition was published in 17513. Today, many different sources of the score exist, primarily including the autograph manuscript P200 and a limited series of copies of the first and second original editions of 1751 and 1752, respectively4. Over time, many unsettled issues have continued to vex scholars and musicians. These issues can be summarised as follows: a. The explanation of the differences in the music score between manuscript P200 and the original edition. -

SQUILT Lesson

Please enjoy this complimentary SQUILT lesson. If you enjoy this lesson, you can purchase the SQUILT curriculum, which includes many lessons similar to this one, grouped by musical era. If you mention this lesson on your blog or website, please link back to my page. Do not distribute this lesson without my permission. Thanks! Mary @ Homegrown Learners & SQUILT Music The goal of a SQUILT lesson is to give your child exposure to a piece of beautiful music and to train their ears to listen for the elements of music. It's not so much about filling in the SQUILT notebooking page “correctly” as it is developing attention, discrimination, and appreciation (skills that translate into so much more than music appreciation). SQUILT lessons can include a little or a lot – as the parent you should judge how much your child can handle in one sitting. It is a wonderful day when your child hears a piece of music and starts talking with you about its finer points! Disclaimer: Each SQUILT lesson includes outside links – many of them YouTube links. As with everything on the internet, please preview these before showing them to your children. I cannot be responsible for comments made on videos or other things of this nature. © Mary Prather - Homegrown Learners, LLC - 2014 Instructions for the Lesson: SQUILT stands for Super Quiet UnInterrupted Listening Time. Play the piece of music for your child. During the first listening, the child is asked to be “Super Quiet” and listen to the entire piece of music (preferably with their eyes closed). {Preface this first listening by going over the SQUILT notebooking sheet and prepping them for what they will be listening for: dynamics, rhythm/tempo, instrumentation, and mood. -

Form Exam, Section 2: 18Th-Century Fugal Analysis (8 Questions)

Form exam, Section 2: 18th-century Fugal Analysis (8 questions) This exam section asks about a Bach fugue from The Well-Tempered Clavier Format of this section of the Exam: Questions: (the exact measure numbers are left blank here but they are given on the exam): (a) What are measures _______ known as? [what fugal term describes those measures] (b) What is the upper voice in measures ______ known as? [what fugal term describes it] (c) What term is used to identify measures ______ ? [what fugal term describes that part of the fugue] (d) What term is used to identify measures ______ ? [what fugal term describes that part of the fugue] (e) What is the contrapuntal technique that is used in measures ______? The possible answer choices for the above questions are: - subject: the main melodic idea of the fugue - answer: the subject but transposed to a different pitch level - exposition: section of a fugue where some version of the subject is stated; a fugue starts with a "tonic exposition" in which all the voices of the fugue get to state some version of the subject - countersubject: a melodic idea the appears in counterpoint against the subject more than once - episode: the opposite of an exposition; episodes are sections that modulate to new keys between expositions - augmentation: make the rhythm values of the subject longer - diminution= make the rhythm values of the subject shorter - inversion: turn the melodic intervals of the subject upside down; "retrograde" is to state the subject backwards from last note to first - stretto: multiple statements of the subject that occur closely on top of each other to create tension near the end of a fugue—Example below is from Fugue 11 in F major from The Well-tempered Clavier, Book1 (the subject is highlighted in grey at m.37--there are overlapping subject entries at m. -

J.S. Bach's the Art of Fugue

Uri Golomb Johann Sebastian Bach’s The Art of Fugue In the introduction to his book Musical Meaning and Emotion, philosopher Stephen Davies wrote: “I do not believe that all music is expressive. Neither do I believe that expressiveness is always the most important feature of music that is expressive” (p. x). To illustrate this, he presented Bach’s Art of Fugue as the archetypal example. Here, he claims, is a work in which the listener’s attention should be drawn to “the way the material is handled”; the music’s “expressive and dynamic features” – or lack thereof – are of marginal importance (p. 354). This view is not atypical. The Art of Fugue’s reputation as a cerebral, intellectual work is so pervasive that Rinaldo Alessandrini, in the notes to his recording, was moved to ask: “is it possible to consider The Art of Fugue as music?” Until recently, The Art of Fugue was considered Bach’s very last work, sketched and written in last years of his life. It thus came to be viewed as Bach’s “Last Will and Testament”. This resonated with the more general tendency to consider any artist’s late works as transcendental, “unworldly” reflections of their creator’s spirit. Much was also made of the fact that the work was published with no indication of instrumentation: this was seen as further evidence for Bach’s disengagement from material considerations, his indifference to sonority and performance. Some even described The Art of Fugue as Augenmusik – “eye-music”, which should be contemplated and analysed, not realised in sound. -

Fugue for Drumset

Sound Enhanced Hear a MIDI file of the example marked in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site, www.pas.org Fugue for Drumset BY MICHAEL PETIFORD fugue is a polyphonic composition based on canonic imi- Thus, an ascending phrase becomes a descending phrase, and tation. In other words, it comprises multiple melodic vice versa. Low notes and high notes swap places. Alines that are played simultaneously, with a leading voice Augmentation. In augmentation the note values of the subject that states a melodic subject and following voices that enter are increased uniformly, extending the overall length of the later and imitate the subject. melody. For instance, doubling the value of each note will double As with a canon, the voices in a fugue enter in succession and the overall length of the melody. A two-measure subject would may apply variations to the subject; however the fugue provides thus become a four-measure variation. even greater opportunity for musical expression by allowing the Diminution. In diminution the overall note values of the sub- participating voices to introduce secondary melodic material, ject are decreased, shortening the length of the melody. For in- and by imposing structural elements that allow the individual stance, halving the value of each note would cut the overall voices to behave more independently. Unlike a canon, in which length of the melody in half. In this case, a two-measure subject the following voices are imitations of the subject, in a fugue all would become a one-measure variation. of the voices participate on a relatively equal level.