The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach Konstantinos Alevizos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MTO 19.3: Brody, Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach

Volume 19, Number 3, September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn (Cambridge University Press, 2012) Christopher Brody KEYWORDS: Bach, Bach reception, Mozart, fugue, chorale, Well-Tempered Clavier Received July 2013 [1] Historical research on Johann Sebastian Bach entered its modern era in the late 1950s with the development, spearheaded by Alfred Dürr, Georg von Dadelsen, and Wisso Weiss, of the so-called “new chronology” of his works.(1) In parallel with this revolution, the history of the dissemination and reception of Bach was also being rewritten. Whereas Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel wrote, in 1945, that “Bach and his works ... [were] practically forgotten by the generations following his” (358), by 1998 Christoph Wolff could describe the far more nuanced understanding of Bach reception that had arisen in the intervening years in terms of “two complementary aspects”: on the one hand, the beginning of a more broadly based public reception of Bach’s music in the early nineteenth century, for which Mendelssohn’s 1829 performance of the St. Matthew Passion represents a decisive milestone; on the other hand, the uninterrupted reception of a more private kind, largely confined to circles of professional musicians, who regarded Bach’s fugues and chorales in particular as a continuing challenge, a source of inspiration, and a yardstick for measuring compositional quality. (485–86) [2] In most respects it is with the latter (though chronologically earlier) aspect that Matthew Dirst’s survey Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn concerns itself, serving as a fine single-volume introduction to the “private” side of Bach reception up to about 1850. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Bach: a Beautiful Mind Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Concert Hall 2 Bach: a Beautiful Mind Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Concert Hall Important Information Allowed in the Hall

Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Milton Concert Jan, Hall 19 Sun Bach: A Beautiful Mind Sat 18 & Sun 19 Jan Milton Court Concert Hall Part of Barbican Presents 2019–20 Bach: A Beautiful Mind 1 Important information When does the I’m running late! Please… Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Milton Concert Jan, Hall 19 Sun concert start Latecomers will be Switch any watch and finish? admitted if there is a alarms and mobile The first concert begins suitable break in the phones to silent during at 2pm. performance. the performance. The second concert begins at 7.30pm. Please don’t… Use a hearing aid? Need a break? Take photos or Please use our induction You can leave at any recordings during the loop – just switch your time and be readmitted if performance – save it hearing aid to T setting there is a suitable break for the curtain call. on entering the hall. in the performance, or during the interval. Looking for Looking for Carrying bags refreshment? the toilets? and coats? Bars are located on The nearest toilets, Drop them off at our free Levels 1 and 2. Pre-order including accessible cloak room on Level -1. interval drinks to beat the toilets, are located on the queues. Drinks are not Ground Floor and Level Bach: A Beautiful Mind allowed in the hall. 2. There are accessible toilets on every level. 2 Welcome to today’s performances Today sees the concluding part of Accademia Bizantina under its director Bach: A Beautiful Mind, our weekend Ottavio Dantone. exploring the multi-faceted genius of The final concert celebrates Bach’s J S Bach, curated by Mahan Esfahani. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in JS Bach's Organ Fugues

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in J. S. Bach’s Organ Fugues BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao BFA, National Taiwan Normal University, 1999 MA, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2002 MEd, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2003 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA Abstract This study explores the musical-rhetorical tradition in German Baroque music and its connection with Johann Sebastian Bach’s fugal writing. Fugal theory according to musica poetica sources includes both contrapuntal devices and structural principles. Johann Mattheson’s dispositio model for organizing instrumental music provides an approach to comprehending the process of Baroque composition. His view on the construction of a subject also offers a way to observe a subject’s transformation in the fugal process. While fugal writing was considered the essential compositional technique for developing musical ideas in the Baroque era, a successful musical-rhetorical dispositio can shape the fugue from a simple subject into a convincing and coherent work. The analyses of the four selected fugues in this study, BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582, will provide a reading of the musical-rhetorical dispositio for an understanding of Bach’s fugal writing. ii Copyright © 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements The completion of this document would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. -

Organ Interpretation Competition for the Johann Pachelbel Award at the 69Th ION Music Festival 26 June - 02 July 2020

Organ Interpretation Competition for the Johann Pachelbel Award at the 69th ION Music Festival 26 June - 02 July 2020 A WARM INVITATION TO NUREMBERG For 52 years, young artists have been invited to come to Nuremberg in early summer to give proof of their artistic prowess to a jury comprised of prominent experts. The climax of this process has always been the presentation of the widely known Johann Pachelbel Award. And so again we issue an invitation to register for this prestigious international interpretation competition in 2020. What is it all about? The organ interpretation competition is looking for organists who in their young careers have already achieved independent interpretation of significant works of organ literature. But it will also seek interaction with contemporary works. And expect competitors to be able to deal with both the soundscapes and playing technique of historical organs and to cope with the possibilities and challenges of modern instruments. At the same time, this interpretation competition explicitly demands not only technical skills, but also looks for interpretations which are courageous, sometimes leaving matters open, finding new aspects in well-known works, and eliciting unique sounds from the instruments themselves – feeding on the tension between tradition and future perspectives. And of course, the sequence of works, the organists’ programming and sometimes the link between the individual compositions to be played is of special interest to the jurors. This is all about a contemporary way of dealing with the history of music and instruments. From the first round on, the competition will be public. The final will be an integral element of the festival programme of the 69th ION Music Festival, staged in the world famous Old Town of Nuremberg, and played on the Peter organ of St Sebaldus’ Church. -

'Modern Baroque'

‘Modern Baroque’ ‘Approaches and Attitudes to Baroque Music Performance on the Saxophone’ Jonathan Byrnes 4080160 Masters of Music Projecto Cientifico IV ESMAE 2010 1 Contents Page ‘Introduction’ (Prelude) 4 ‘Education’ (Allemande) 7 ‘Performance’ (Courante) 12 ‘Morality – Responsibility and Reasons.’ (Sarabande) 18 ‘Transcription or adaptation’ – note for note transcription (Minuet I) 36 ‘Transcription or adaptation’ – adaptation (Minuet II) 58 Conclusion (Gigue) 70 ‘Bibliography’ 73 ‘Discography’ 77 ‘Internet Resourses’ 78 2 Thank you. This Masters Thesis would not have been possible without the help and assistance from the people below. I would like to thank them sincerely for all their guidence and support. Sofia Lourenço, Henk Van Twillert, Fernando Ramos, Gilberto Bernardes, Madelena Soveral, Dr. Cecília, Filipe Fonseca, Luís Lima, Nicholas Russoniello, Cláudio Dioguardi, Cármen Nieves, Alexander Brito, Donny McKenzie, Andy Harper, Thom Chapman, Alana Blackburn, Paul Leenhouts, Harry White, And of course my family. Without these people, I am sure I would not have achieved this work. 3 1. Introduction (Prelude) Baroque music has been part of the saxophone repertoire in one form or another since the instruments creation, as it so happened to coincide with the Baroque revival. ‘It was Mendelssohn's promotion of the St Matthew Passion in 1829 which marked the first public "revival" of Bach and his music’ 1, either through studies or repertoire the music of the baroque period has had an important role in the development of the majority of all saxophonists today. However the question remains. What function does this music have for a modern instrumentalist and how should this music be used or performed by a saxophonist? Many accolades have been given of saxophone performances of Baroque music. -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

The Design of P200: Mensural Quantity and Proportion in the Early Version of the Art of Fugue

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2013 THE DESIGN OF P200: MENSURAL QUANTITY AND PROPORTION IN THE EARLY VERSION OF THE ART OF FUGUE Joel Thomas Runyan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Runyan, Joel Thomas, "THE DESIGN OF P200: MENSURAL QUANTITY AND PROPORTION IN THE EARLY VERSION OF THE ART OF FUGUE" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 79. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/79 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Fugue in C Minor the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1

chapter 2 Fugue in C Minor The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 Bach’s very best-known fugue must be the Fugue in C Minor from book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier. It has become stan- dard teaching material in advanced and elementary textbooks alike, for courses in canon and fugue as well as lowly Music Appreciation. It was the first fugue to be jazzed and the first to be switched on. Heinrich Schenker, lord and master of mod- ern music theory, settled on it as the example to expound in a classic essay, “Organicism in Fugue,” which recently pro- voked an entire critical chapter from Laurence Dreyfus in his book Bach and the Patterns of Invention. When The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians dropped Roger Bullivant’s solid article “fugue” from its second edition, what replaced it was (among other things) a blow-by-blow analysis of the Fugue in C Minor. There is a manuscript copied by one of Bach’s students con- taining analytical annotations to this work. (Some are given by David Schulenberg in The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach.) “For the use and improvement of musical youth eager to learn,” reads the 10 Fugue in C Minor / 11 title page for the WTC; did the Fugue in C Minor occupy a spe- cial place in the composer’s personal curriculum? One can even detect a mild backlash as regards the piece, as when Bullivant reaches the chapter on fugal form in his book on fugue and says he will look “not at the standard examples (WTC I C-Minor is the great favorite for an introduction to Bach’s tech- nique, WTC I C-Major being, for good reasons, beyond the understanding of the conventional theorist!) but at some of the more ‘difficult’ and, it is hoped, interesting forms.” Assuming that Bach wanted to exhibit something minimal at (or very near) the beginning of his exemplary collection of preludes and fugues, C Minor indeed presented itself as a prime candidate. -

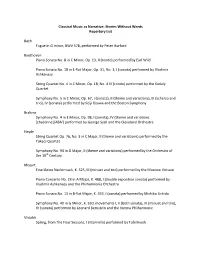

Classical'music'as'narrative

Classical'Music'as'Narrative:'Stories'Without'Words' Repertory'List' ! Bach! ! Fugue!in!G!minor,!BWV!578,!performed!by!Peter!Hurford! ! Beethoven! Piano!Sonata!No.!8!in!C!Minor,!Op.!13,!II!(rondo)!performed!by!Earl!Wild! ! Piano!Sonata!No.!18!in!ELflat!Major,!Op.!31,!No.!3,!I!(sonata)!performed!by!Vladimir! Ashkenazy! ! String!Quartet!No.!4!in!C!Minor,!Op.!18,!No.!4!IV!(rondo)!performed!by!the!Kodaly! Quartet! ! Symphony!No.!5!in!C!Minor,!Op.!67,!I!(sonata),!II!(theme!and!variations),!III!(scherzo!and! trio),!IV!(sonata)!performed!by!Seiji!Ozawa!and!the!Boston!Symphony! ! Brahms! Symphony!No.!4!in!E!Minor,!Op.!98,!I!(sonata),!IV!(theme!and!variations! [chaconne]/ABA’)!performed!by!George!Szell!and!the!Cleveland!Orchestra! ! Haydn!! String!Quartet!Op.!76,!No.!3!in!C!Major,!II!(theme!and!variations)!performed!by!the! Takacs!Quartet! ! Symphony!No.!94!in!G!Major,!II!(theme!and!variations)!performed!by!the!Orchestra!of! the!18th!Century! ! Mozart! Eine!kleine!Nachtmusik,!K.!525,!III!(minuet!and!trio)!performed!by!the!Moscow!Virtuosi! ! Piano!Concerto!No.!23!in!A!Major,!K.!488,!I!(double!exposition!sonata)!performed!by! Vladimir!Ashkenazy!and!the!Philharmonia!Orchestra! ! Piano!Sonata!No.!13!in!BLflat!Major,!K.!333,!I!(sonata)!performed!by!Michiko!Uchida! ! Symphony!No.!40!in!G!Minor,!K.!550,!movements!I,!II!(both!sonata),!III!(minuet!and!trio),! IV!(sonata)!performed!by!Leonard!Bernstein!and!the!Vienna!Philharmonic! ! Vivialdi!! Spring,!from!The!Four!Seasons,!I!(ritornello)!performed!by!Tafelmusik! ! ! ! Music'Appreciation'Texts' ! Here!are!three!good!reference!textbooks!that!cover!the!forms!and!some!of!the!pieces!we!have! studied.!All!have!accompanying!CDs,!which!are!sold!separately.!The!latest!editions!are! expensive,!but!they!are!no!better!than!the!older!editions,!which!are!not.!So!look!for!any!nonL current!edition—the!cheaper!the!better!! ! Roger!Kamien,!Music:!An!Appreciation! ! Joseph!Kerman,!Listen! ! James!Machlis,!Kristine!Forney,!The!Enjoyment!of!Music! ! ! ! ' ' ' ' ! ! ! !. -

An Exploration of Musical Form Featuring Bach's Fugue in G Minor

WHAT THE FUGUE? An exploration of musical form featuring Bach’s Fugue in G minor Presented by Alex Pierson and Logan Tolman Performance by the Caine Brass Quintet What exactly is a fugue? (fyo͞ oɡ) A fugue is a contrapuntal* composition in which a short melody or phrase (the subject) is introduced by one part and successively taken up by others and developed by interweaving the parts. *Counterpoint: The art or technique of setting, writing, or playing a melody or melodies in conjunction with another, according to fixed rules. Image credit: Crystal Broderick Counterpoint • Music that focuses on individual and independent lines of music that interplay with each other. • Focuses on musical lines rather than chords or chord progressions • Artfully moves from dissonant intervals to consonant intervals between the separate lines. Subject • The main theme • Introduced by the first voice/player • This is what will repeat and vary slightly throughout the piece Answer • A response to the subject based off of the same musical theme • May or may not use the same intervals as the theme • Always starts on a different pitch than the subject Counter Subject • A secondary theme, like the subject, that gets passed around between voices/parts and is developed throughout the piece • Usually appears when a voice is beginning an answer Episode • Sections of the piece after all the voices/parts have been introduced where no part of the subject is present • All the voices are interplaying and developing other ideas that have been presented • Alternates with Entries throughout the rest of the piece I don’t see the Subject….