Fugue in C Minor the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

LISTENING GUIDE Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770–1827) Symphony No

LISTENING GUIDE Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Opus 67 • Composed 1803–1808 1st Performance in Vienna, December 22, 1808 Movement I Allegro con brio FORM: SONATA ALLEGRO EXPOSITION 1st Theme 1. 1st THEME introduced by two strong UNISONS. U U bb 2 ‰ ‰ & b 4 œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ ˙ ˙ 2. Close IMITATION leads to _______ CHORDS. Which INSTRUMENT “hangs on”? 3. Another (very loud) UNISON restarts the action. Transition 4. ASCENDING SEQUENCE of ____ steps based on ____________. (soft) 5. TRANSITION ends with _____ CHORDS. 2nd Theme 6. 2nd THEME poses Question (in E-FLAT MAJOR) b & b b œ œ œ ˙ ˙ ˙ and receives three simple Answers. b œ œ œ & b b œ œ œ œ œ Closing Section 7. Another stirring CRESCENDO. 8. Joyous idea (still in E-FLAT MAJOR) propels to end of EXPOSITION. ˙ œ œ œ. b bœ œ œ œ œ. œ œ . œ. œ œ . œ & b b œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ j . œ. œ ƒ Entire EXPOSITION repeats from No. 1. DEVELOPMENT 9. Strange twist in 1st THEME announces DEVELOPMENT. 10. Many KEYS visited. Tension builds! 11. RHYTHMIC surprises and SYNCOPATION abound. 12. WINDS and STRINGS engage in IMITATION. 13. Violent DYNAMIC contrasts drive to... RECAPITULATION 1st Theme 14. Two “almost” UNISON statements. 15. Forward motion of RECAPITULATION is interrupted by an _________ SOLO. Transition 16. ASCENDING SEQUENCE of _____ steps. 17. TRANSITION ends with ________ CHORDS. 2nd Theme 18. BASSOONS ask a Question (now in C MAJOR) followed by four simple Answers. -

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in JS Bach's Organ Fugues

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in J. S. Bach’s Organ Fugues BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao BFA, National Taiwan Normal University, 1999 MA, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2002 MEd, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2003 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA Abstract This study explores the musical-rhetorical tradition in German Baroque music and its connection with Johann Sebastian Bach’s fugal writing. Fugal theory according to musica poetica sources includes both contrapuntal devices and structural principles. Johann Mattheson’s dispositio model for organizing instrumental music provides an approach to comprehending the process of Baroque composition. His view on the construction of a subject also offers a way to observe a subject’s transformation in the fugal process. While fugal writing was considered the essential compositional technique for developing musical ideas in the Baroque era, a successful musical-rhetorical dispositio can shape the fugue from a simple subject into a convincing and coherent work. The analyses of the four selected fugues in this study, BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582, will provide a reading of the musical-rhetorical dispositio for an understanding of Bach’s fugal writing. ii Copyright © 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements The completion of this document would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. -

Organ Interpretation Competition for the Johann Pachelbel Award at the 69Th ION Music Festival 26 June - 02 July 2020

Organ Interpretation Competition for the Johann Pachelbel Award at the 69th ION Music Festival 26 June - 02 July 2020 A WARM INVITATION TO NUREMBERG For 52 years, young artists have been invited to come to Nuremberg in early summer to give proof of their artistic prowess to a jury comprised of prominent experts. The climax of this process has always been the presentation of the widely known Johann Pachelbel Award. And so again we issue an invitation to register for this prestigious international interpretation competition in 2020. What is it all about? The organ interpretation competition is looking for organists who in their young careers have already achieved independent interpretation of significant works of organ literature. But it will also seek interaction with contemporary works. And expect competitors to be able to deal with both the soundscapes and playing technique of historical organs and to cope with the possibilities and challenges of modern instruments. At the same time, this interpretation competition explicitly demands not only technical skills, but also looks for interpretations which are courageous, sometimes leaving matters open, finding new aspects in well-known works, and eliciting unique sounds from the instruments themselves – feeding on the tension between tradition and future perspectives. And of course, the sequence of works, the organists’ programming and sometimes the link between the individual compositions to be played is of special interest to the jurors. This is all about a contemporary way of dealing with the history of music and instruments. From the first round on, the competition will be public. The final will be an integral element of the festival programme of the 69th ION Music Festival, staged in the world famous Old Town of Nuremberg, and played on the Peter organ of St Sebaldus’ Church. -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

Beethoven's Fifth Symphony

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM BY LAURIE SHULMAN, ©2017 Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony ONE-MINUTE NOTES Beethoven: Overture to Coriolan. Coriolan is vintage Beethoven: a stormy sonata-form movement in the heroic key of C minor. Jolting chords and lurching accents in the principal theme portray the tortured, indecisive hero. This is Beethoven at his most tragic. Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 3. A kinder, gentler Bartók emerges in the Third Piano Concerto. Nascent neoromanticism blooms in his melodious, folk-inflected first movement. A noble chorale gives way to nature’s night sounds in the slow movement, leading to an exhilarating finale. Beethoven: Symphony No. 5. Fate knocks at the door in symphonic literature’s most famous opening. Beethoven takes us on a journey from struggle to triumph in his magnificent Fifth Symphony. BEETHOVEN: Overture to Coriolan, Op. 62 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Born: December 16, 1770, in Bonn, Germany Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna, Austria Composed: 1807 World Premiere: March 1807 in Vienna NJSO Premiere: 1927–28 season; Philip James conducted. Duration: 8 minutes Beethoven’s overtures vary widely in content and quality. Some are occasional pieces with little dramatic import; others are middle-period masterpieces. The former category includes King Stephen and The Consecration of the House. The latter group is dominated by the three Leonore Overtures and the Overture to Fidelio; plus Egmont and this weekend’s featured overture, Coriolan. What they all share is a connection to staged drama. Beethoven only completed one opera, Fidelio, but we know that he considered several other operatic projects. His Creatures of Prometheus was one of the most popular ballets of the early 19th century. -

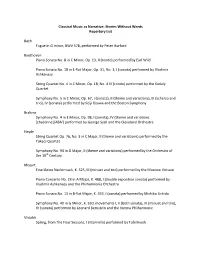

Classical'music'as'narrative

Classical'Music'as'Narrative:'Stories'Without'Words' Repertory'List' ! Bach! ! Fugue!in!G!minor,!BWV!578,!performed!by!Peter!Hurford! ! Beethoven! Piano!Sonata!No.!8!in!C!Minor,!Op.!13,!II!(rondo)!performed!by!Earl!Wild! ! Piano!Sonata!No.!18!in!ELflat!Major,!Op.!31,!No.!3,!I!(sonata)!performed!by!Vladimir! Ashkenazy! ! String!Quartet!No.!4!in!C!Minor,!Op.!18,!No.!4!IV!(rondo)!performed!by!the!Kodaly! Quartet! ! Symphony!No.!5!in!C!Minor,!Op.!67,!I!(sonata),!II!(theme!and!variations),!III!(scherzo!and! trio),!IV!(sonata)!performed!by!Seiji!Ozawa!and!the!Boston!Symphony! ! Brahms! Symphony!No.!4!in!E!Minor,!Op.!98,!I!(sonata),!IV!(theme!and!variations! [chaconne]/ABA’)!performed!by!George!Szell!and!the!Cleveland!Orchestra! ! Haydn!! String!Quartet!Op.!76,!No.!3!in!C!Major,!II!(theme!and!variations)!performed!by!the! Takacs!Quartet! ! Symphony!No.!94!in!G!Major,!II!(theme!and!variations)!performed!by!the!Orchestra!of! the!18th!Century! ! Mozart! Eine!kleine!Nachtmusik,!K.!525,!III!(minuet!and!trio)!performed!by!the!Moscow!Virtuosi! ! Piano!Concerto!No.!23!in!A!Major,!K.!488,!I!(double!exposition!sonata)!performed!by! Vladimir!Ashkenazy!and!the!Philharmonia!Orchestra! ! Piano!Sonata!No.!13!in!BLflat!Major,!K.!333,!I!(sonata)!performed!by!Michiko!Uchida! ! Symphony!No.!40!in!G!Minor,!K.!550,!movements!I,!II!(both!sonata),!III!(minuet!and!trio),! IV!(sonata)!performed!by!Leonard!Bernstein!and!the!Vienna!Philharmonic! ! Vivialdi!! Spring,!from!The!Four!Seasons,!I!(ritornello)!performed!by!Tafelmusik! ! ! ! Music'Appreciation'Texts' ! Here!are!three!good!reference!textbooks!that!cover!the!forms!and!some!of!the!pieces!we!have! studied.!All!have!accompanying!CDs,!which!are!sold!separately.!The!latest!editions!are! expensive,!but!they!are!no!better!than!the!older!editions,!which!are!not.!So!look!for!any!nonL current!edition—the!cheaper!the!better!! ! Roger!Kamien,!Music:!An!Appreciation! ! Joseph!Kerman,!Listen! ! James!Machlis,!Kristine!Forney,!The!Enjoyment!of!Music! ! ! ! ' ' ' ' ! ! ! !. -

An Exploration of Musical Form Featuring Bach's Fugue in G Minor

WHAT THE FUGUE? An exploration of musical form featuring Bach’s Fugue in G minor Presented by Alex Pierson and Logan Tolman Performance by the Caine Brass Quintet What exactly is a fugue? (fyo͞ oɡ) A fugue is a contrapuntal* composition in which a short melody or phrase (the subject) is introduced by one part and successively taken up by others and developed by interweaving the parts. *Counterpoint: The art or technique of setting, writing, or playing a melody or melodies in conjunction with another, according to fixed rules. Image credit: Crystal Broderick Counterpoint • Music that focuses on individual and independent lines of music that interplay with each other. • Focuses on musical lines rather than chords or chord progressions • Artfully moves from dissonant intervals to consonant intervals between the separate lines. Subject • The main theme • Introduced by the first voice/player • This is what will repeat and vary slightly throughout the piece Answer • A response to the subject based off of the same musical theme • May or may not use the same intervals as the theme • Always starts on a different pitch than the subject Counter Subject • A secondary theme, like the subject, that gets passed around between voices/parts and is developed throughout the piece • Usually appears when a voice is beginning an answer Episode • Sections of the piece after all the voices/parts have been introduced where no part of the subject is present • All the voices are interplaying and developing other ideas that have been presented • Alternates with Entries throughout the rest of the piece I don’t see the Subject…. -

The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach Konstantinos Alevizos

Bibliographical anachronism: The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach Konstantinos Alevizos To cite this version: Konstantinos Alevizos. Bibliographical anachronism: The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach. 2021. hal-03161248 HAL Id: hal-03161248 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03161248 Preprint submitted on 5 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Bibliographical anachronism: The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach. A. Criteria to Establish the Progression1. The Art of Fugue is a collection of compositions in an austere contrapuntal style, all of which are based on the same subject. The latest research on the score reveals that Bach started this copious work around 17422. However, it is known that the first edition was published in 17513. Today, many different sources of the score exist, primarily including the autograph manuscript P200 and a limited series of copies of the first and second original editions of 1751 and 1752, respectively4. Over time, many unsettled issues have continued to vex scholars and musicians. These issues can be summarised as follows: a. The explanation of the differences in the music score between manuscript P200 and the original edition. -

How to Prepare for the Music Fundamentals Test

How to Prepare for the Music Fundamentals Test On your audition day, you will be given a brief written music fundamentals test. Its purpose is to determine whether or not you are ready to begin Music Theory I and Aural Skills I during your first semester at Wheaton. The test is graded pass/fail, and both accuracy and time are factored into the results. Even if you have already taken music theory or aural skills classes, the test is mandatory. To prepare for the test, memorize the following: • Note names in both treble and bass clefs. • The relationships between basic note values (i.e., whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, 8th notes, and 16th notes), as well as their equivalent rests. • The meanings of dots, ties, and beams. • The meanings of 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 (C), 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8 signatures. • All 30 major and natural minor scales in treble and bass clefs. • All 30 major and minor key signatures in treble and bass clefs. If you are unfamiliar with any of the concepts listed above, desire clarification on them, or want to practice them, you are encouraged to visit the following websites: www.musictheory.net www.teoria.com www.emusictheory.com Revised April 2012 Scale and Key Signature Memorization Guide Major Scale Natural Minor Scale Key Signature C♭ Major C♭ D♭ E♭ F♭ G♭ A♭ B♭ C♭ A♭ Minor A♭ B♭ C♭ D♭ E♭ F♭ G♭ A♭ G♭ Major G♭ A♭ B♭ C♭ D♭ E♭ F G♭ E♭ Minor E♭ F G♭ A♭ B♭ C♭ D♭ E♭ D♭ Major D♭ E♭ F G♭ A♭ B♭ C D♭ B♭ Minor B♭ C D♭ E♭ F G♭ A♭ B♭ A♭ Major A♭ B♭ C D♭ E♭ F G A♭ F Minor F G A♭ B♭ C D♭ E♭ F E♭ Major E♭ F G A♭ B♭ C D E♭ C Minor C D