Press Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seafood Soup & Salad Meats Vegetables Extras

SOUP & SALAD SEAFOOD MEATS Miso Tuna Salad Turtle Soup Certified Japanese Wagyu miso marinated tuna, spicy tuna carpaccio, topped with sherry 9 / 18 ruby red grapefruit ponzu and crispy shallots spinach and wakame salad, dashi vinaigrette, 14 per oz (3 oz minimum) Fried Chicken & Andouille Gumbo sesame chip 14 a la Chef Paul 9 Fried Smoked Oysters Grilled Sweetbreads bourbon tomato jam, white remoulade 14 charred polenta cake, sherry braised cipollini Pickled Shrimp Salad onion, chimmichurri, sauce soubise 15 lolla rosa, Creole mustard vinaigrette, Crabmeat Spaetzle Italian cherry peppers, Provolone, prosciutto, Creole mustard dumplings, jumbo lump crab, Beef Barbacoa Sopes roasted corn, green tomato chow chow 10 / 20 green garbanzos, brown butter 12 crispy masa shell, red chili braised beef, queso fresco, pickled vegetables, avocado crema 11 City Park Salad Brown Butter Glazed Flounder & Crab baby red oak, romaine, granny smith apples, almond butter, green beans, lemon gelée, Golden City Lamb Ribs Stilton blue, applewood smoked bacon 8 / 16 almond wafer 16 Mississippi sorghum & soy glaze, fermented bean paste, charred cabbage, BBQ Shrimp Agnolotti Cheese Plate fried peanuts 13 / 26 chef’s selection of cheeses, quince paste, white stuffed pasta, BBQ and cream cheese filling, truffle honey, hazelnuts & water crackers 15 lemon crème fraîche, Gulf shrimp 13 / 26 Vadouvan Shrimp & Grits Rabbit Sauce Piquante vadouvan, garam masala, broken rice grits, slow braised leg, tasso jambalaya stuffing, VEGETABLES housemade chili sauce, fresh yogurt -

The Good Food Doctor: Heeats•Hesh Ots•Heposts

20 Interview By Dr Hsu Li Yang, Editorial Board Member The Good Food Doctor: heeats•hesh ots•heposts... Hsu Li Yang (HLY): Leslie, thank you very much for agreeing to participate in this interview with the SMA News. What made you start this “ieatishootipost” food blog? Dr Leslie Tay (LT): I had been overseas for a long time and when I finally came back to Singapore, I began to appreciate just how much of a Singaporean I really am. You know, my perfect breakfast would be two roti prata with a cup of teh tarik or kopi and kaya toast. Sometimes I feel we take our very own Singapore food for granted, that is, until we live overseas. About two years ago, I suddenly felt that even is day job is that of a family doctor though I love Singapore food, I don’t really know (one of two founding partners where all the good stuff is – where’s the best hokkien mee, the best chicken rice and so on. So I decided, of Karri Family Clinic) in the H okay, let’s go and try all these food as a hobby. When Tampines heartlands. But Dr Leslie Tay is I was young, my father never really brought us out far better known for his blog and forum at to eat at all the famous hawker places, because he http://ieatishootipost.sg/. With more than believed in home-cooked food. 150,000 unique visitors each month and a busy forum comprising more than 1,000 I started researching on the internet, going to members, Dr Tay is the most read and (online) forums, seeking out people who know influential food blogger in the country. -

{Download PDF} Jakarta: 25 Excursions in and Around the Indonesian Capital Ebook, Epub

JAKARTA: 25 EXCURSIONS IN AND AROUND THE INDONESIAN CAPITAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Whitmarsh | 224 pages | 20 Dec 2012 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804842242 | English | Boston, United States Jakarta: 25 Excursions in and around the Indonesian Capital PDF Book JAKARTA, Indonesia -- A jet carrying 62 people lost contact with air traffic controllers minutes after taking off from Indonesia's capital on a domestic flight on Saturday, and debris found by fishermen was being examined to see if it was from the missing plane, officials said. Bingka Laksa banjar Pekasam Soto banjar. Recently, she spent several months exploring Africa and South Asia. The locals always have a smile on their face and a positive outlook. This means that if you book your accommodation, buy a book or sort your insurance, we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. US Capitol riots: Tracking the insurrection. The Menteng and Gondangdia sections were formerly fashionable residential areas near the central Medan Merdeka then called Weltevreden. Places to visit:. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Some traditional neighbourhoods can, however, be identified. Tis' the Season for Holiday Drinks. What to do there: Eat, sleep, and be merry. Special interest tours include history walks, urban art walks and market walks. Rujak Rujak cingur Sate madura Serundeng Soto madura. In our book, that definitely makes it worth a visit. Jakarta, like any other large city, also has its share of air and noise pollution. We work hard to put out the best backpacker resources on the web, for free! Federal Aviation Administration records indicate the plane that lost contact Saturday was first used by Continental Airlines in Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Expat Singapore.Pdf

SINGAPORE An everyday guide to expatriate life and work. YOUR SINGAPORE COUNTRY GUIDE Contents Overview 1 Employment Quick Facts 1 The job market 7 Getting Started Income tax 7 Climate and weather 2 Business etiquette 7 Visas 3 Retirement 7 Accommodation 3 Finance Schools 3 Currency 8 Culture Cost of living 8 Language 4 Banking 8 Social etiquette and faux pas 4 Cost of living chart 9 Eating 4 Drinking 4 Health Holidays 5 Private Medical Insurance 8 Emergencies BC Transport 6 Vaccinations BC Getting In Touch Health Risks BC Telephone 6 Pharmacies BC Internet 6 Postal services 6 Quick facts Capital: Singapore Population: 5.6 million Major language: English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil Major religion: Buddhism, Christianity Currency: Singapore Dollar (SGD) Time zone: GMT+8 Emergency number: 999 (police), 995 (ambulance, fire) Electricity: 230 volts, 50Hz. Three-pin plugs with flat blades are used. Drive on the: Left http://www.expatarrivals.com/singapore/essential- info-for-singapore Overview Singapore is a buzzing metropolis with a fascinating mix of nationalities and cultures that promote tolerance and harmony. Expats can take comfort in the knowledge that the island city- state is clean and safe. Renowned for its exemplary and efficient public transport and communications infrastructure, Singapore is also home to some of the best international schools and healthcare facilities in the world. In the tropical climate that Singapore boasts, expats can look forward to a relaxed, outdoor lifestyle all year round. Its location, situated off the southern coast of Malaysia, also makes Singapore an ideal base from which to explore other parts of Asia. -

Foodie-2019.Pdf

I’M A FOODIE A GUIDE FOR FOODIES / 02 - CONTENTS & MAD ABOUT MOD-SIN / Passion Made Possible MAD ABOUT Singapore is much more than the sum of its numerous attractions. It’s constantly evolving, reinventing, and reimagining itself, MOD-SIN with people who are passionate about creating new possibilities. Coined by Chef Willin Low of Relish by Wild Rocket, Mod-Sin refers to modern Singaporean cuisine that fuses innovative cooking techniques It’s where foodies, explorers, collectors, and new flavours with traditional local favourites. From Rendang Oxtail action seekers, culture shapers, and socialisers meet – and new experiences are Pappardelle to Bak Chor Mee Grilled Cheese, there’s plenty of unique created every day. flavours for you to savour. Here are some foodie favourites. Don’t stop at finding out what you can do when you visit. Let our Passion Ambassadors show you what you can be when you’re here. Because we’re more than just a destination. We’re where passion is CHEF HAN LIGUANG made possible. OF RESTAURANT LABYRINTH Q: What is the concept of Labyrinth? A: “The idea of Labyrinth is to basically take diners on a journey, as well as show then Singapore over a WHERE FOODIES MEET. 3-hour gastronomical adventure in the restaurant itself. Labyrinth was born out of my passion for cooking. I was not a chef or rather I was not a conventional chef. I was Every meal is a chance to indulge in previously a banker. Back in my university days, when something different, in new atmospheres, I was studying in London, I loved cooking and cooking Image credits:Xiao Ya Tou transports me to a very different dimension, where I am and in new ways. -

Food Stories: Culinary Links of an Island State and a Continent Cecilia Y

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2011 Food stories: culinary links of an island state and a continent Cecilia Y. Leong-Salobir University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Leong-Salobir, C. Y. (2011). Food stories: culinary links of an island state and a continent. In I. Patrick. Austin (Eds.), Australia- Singapore Relations: Successful Bilateral Relations in a Historical and Contemporary Context (pp. 143-158). Singapore: Faculty Business and Law, Edith Cowan University. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Food stories: culinary links of an island state and a continent Abstract Foodways has increasingly become an important lens for the analysis of historical, social and cultural studies. Anthropologists and historians in particular view food consumption as ways of understanding cultural adaptation and social grouping. The food practices of a social grouping reveal rich dimensions of people's lives, indicating their sense of identity and their place within the wider community. As well, food is one of the most visible aspects of a community's cultural tradition. It is through food too that a social grouping "borrows" food practices and appropriate food items from other cultures to make them its own. This chapter intends to examine the ways in which cross-cultural links are fostered between nations through the food practices of their people. Keywords food, culinary, continent, state, island, links, stories Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Leong-Salobir, C. -

August 9, 2010

WHERESF: Where to Get It Strait: Strait's Restaurant & Lounge Honors Singapore's Independence Day! WHERESF's Notes Where to Get It Strait: Strait's Restaurant & Lounge Honors Singapore's Independence Day! Yesterday at 3:41pm Chris Yeo’s Straits Restaurant + Lounge Honors Singapore’s Independence Day!! Chris Yeo, founder of Straits Restaurant + Lounge, rolls out the red carpet to honor Singapore’s Independence Day with a month-long “Passport to Singapore” celebration. For four weeks beginning on today, Mon., August 9 -- the 45th anniversary of Singapore’s independence -- Straits Restaurant + Lounge will feature a special weekly menu that takes guests on a culinary excursion highlighting the cultural diversity, cosmopolitan flair, and passion for great cuisine that are hallmarks of Yeo’s native Singapore. Each Straits Restaurant + Lounge location -- San Francisco’s Westfield Shopping Centre and Burlingame, Santana Row in San Jose-- will feature the following special menus that shine a spotlight on Singapore’s melting pot of culinary influences from India, China, Malaysia and Indonesia: August 9 - 15 -- India Roti w/ Palak Paneer (spinach and cottage cheese); Yellow Curried Chick Pea Soup with Samsosa; Lamb Skewers; Roasted Cauliflower Puree; Green Curried Spinach; Naan Bread; Butter Chicken; Kaali Daal (black lentils); Saffron Mango Ice Cream; and Mint Coulis. August 16 - 22 -- China Appetizer Trio of Homemade Potsticker, Kung Pao Chicken Lollipop, Chinese Roast Pork; Black Pepper Short Ribs w/ Bok Choy; Char Siu Marinaded Seabass; Yang Chow Fried Rice; and Red Bean Shaved Ice with Fresh Fruits. August 23 - 29 -- Malaysia Roti; Mixed Satay; Nasi Lemak; Beef Rendeng; and Pisang Goreng (banana coconut pudding). -

From Natural History to National Kitchen: Food in the Museums of Singapore, 20062017

From Natural History to National Kitchen: Food in the Museums of Singapore, 20062017 By: Nicole Tarulevicz and Sandra Hudd Abstract Taking museum exhibitions, publications, and restaurants as a focus, this essay explores how food is used and represented in museums in Singapore, revealing a wider story about nationalism and identity. It traces the transition of food from an element of exhibitions, to a focus of exhibitions, to its current position as an appendage to exhibition. The National Museum is a key site for national meaningmaking and we examine the colonial natural history drawings of William Farquhar in several iterations; how food shortages during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore during World War II have been used for nationbuilding; and hawker food as iconography and focus of culinary design objects. Issues of national identity within a multi ethnic society are then highlighted in the context of the National Kitchen restaurant at the National Gallery of Singapore. Key Words: Singapore, museums, hawker food, memory, nation building Introduction From Berlin’s Deutsches Currywurst Museum to Seoul’s Museum Kimchikan (formerly Kimchi Museum), food is increasingly taking center stage in museums. Food also makes regular appearances in conventional museums and galleries, be that the Julia Child exhibition at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D. C., or an exhibition on food cravings at London’s Science Museum. New Zealand’s giant kiwifruit is just one of very many giant tributes intended to attract tourists. The Southeast Asian citystate of Singapore is well known as a foodie destination and it should come as no surprise that there has been a growing interest, in the last decade, in including food and foodways as content in Singapore’s cultural institutions. -

Yamazato En Menu.Pdf

グランドメニュー Grand menu Yamazato Speciality Hiyashi Tofu Chilled Tofu Served with Tasty Soy Sauce ¥ 1,300 Agedashi Tofu Deep-fried Tofu with Light Soy Sauce 1,300 Chawan Mushi Japanese Egg Custard 1,400 Tori Kara-age Deep-fried Marinated Chicken 1,800 Nasu Agedashi Deep-fried Eggplant with Light Soy Sauce 2,000 Yasai Takiawase Assorted Simmered Seasonal Vegetables 2,200 Kani Kora-age Deep-fried Crab Shell Stuffed with Minced Crab and Fish Paste 2,800 Main Dish Tempura Moriawase Assorted Tempura ¥ 4,000 Yakiyasai Grilled Assorted Vegetables 2,600 Sawara Yuko Yaki Grilled Spanish Mackerel with Yuzu Flavor 3,000 Saikyo-yaki Grilled Harvest Fish with Saikyo Miso Flavor 3,200 Unagi Kabayaki Grilled Eel with Sweet Soy Sauce 7,800 Yakimono Grilled Fish of the Day current price Yakitori Assorted Chicken Skewers 2,200 Sukini Simmered Sliced Beef with Sukiyaki Sauce 8,500 Wagyu Butter Yaki Grilled Fillet of Beef with Butter Sauce 10,000 Rice and Noodle Agemochi Nioroshi Deep-fried Rice Cake in Grated Radish Soup ¥ 1,700 Tori Zosui Chicken and Egg Rice Porridge 1,300 Yasai Zosui Thin-sliced Vegetables Rice Porridge 1,300 Kani Zosui King Crab and Egg Rice Porridge 1,800 Yasai Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Yasai Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Tempura Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tempura Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tendon Tempura Bowl Served with Miso Soup and Pickles 5,200 Una-jyu Eel Rice in Lacquer Box Served with Miso Soup 8,800 A la Carte Appetizers Yakigoma Tofu Seared -

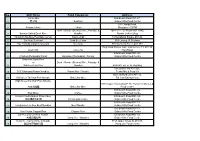

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address Chi Le Ma 505 Beach Road #01-87, 1 吃了吗 Seafood Golden Mile Food Center 307 Changi Road, 2 Katong Laksa Laksa Singapore 419785 Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 168 Lor 1 Toa Payoh #01-1040, 3 Benson Salted Duck Rice Noodles Maxim Coffee Shop 4 Kampung Kia Blue Pea Nasi Lemak Nasi Lemak 10 Sengkang Square #01-26 5 Sin Huat Seafood Crab Bee Hoon 659 Lorong 35 Geylang 6 Hoy Yong Seafood Restaurant Cze Cha 352 Clementi Ave 2, #01-153 Haig Road Market and Food Centre, 13, #01-36 7 Chef Chik Cze Cha Haig Road 505 Beach Road #B1-30, 8 Charlie's Peranakan Food Eurasian / Peranakan / Nonya Golden Mile Food Centre Sean Kee Duck Rice or Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 9 Sia Kee Duck Rice Noodles 659-661Lor Lor 35 Geylang 665 Buffalo Rd #01-326, 10 545 Whampoa Prawn Noodles Prawn Mee / Noodle Tekka Mkt & Food Ctr 466 Crawford Lane #01-12, 11 Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle Bak Chor Mee Tai Hwa Eating House High Street Tai Wah Pork Noodle 531A Upper Cross St #02-16, Hong Lim Market & 12 大崋肉脞麵 Bak Chor Mee Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-49, 13 Kopi More Coffee Golden Mile Food Centre Hainan Fried Hokkien Prawn Mee 505 Beach Road #B1-34, 14 海南福建炒虾麵 Fried Hokkien Mee Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-21, 15 Longhouse Lim Kee Beef Noodles Beef Noodle Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #01-73, 16 Yew Chuan Claypot Rice Claypot Rice Golden Mile Food Centre Da Po Curry Chicken Noodle 505 Beach Road #B1-53, 17 大坡咖喱鸡面 Curry Mee / Noodles Golden Mile Food Centre Heng Kee Curry Chicken Noodle 531A -

300Sensational

300 sensational soups Introduction Fresh from the Garden Pumpkin Soup with Leeks and Ginger Butternut Squash Soup with Nutmeg sensational Vegetable Soups Soup Stocks Cream Cream of Artichoke Soup 300 Curried Butternut Squash Soup with Stock Basics Cream of Asparagus Soup White Chicken Stock Toasted Coconut and Golden Raisins Lemony Cream of Asparagus Soup Roasted Winter Squash and Apple Soup Brown Chicken Stock Hot Guacamole Soup with Cumin and Quick Chicken Stock Spicy Winter Squash Soup with Cheddar Cilantro Chile Croutons Chinese Chicken Stock Cream of Broccoli Soup with Bacon Bits Japanese Chicken Stock Pattypan and Summer Squash Soup with Broccoli Buttermilk Soup Avocado and Grape Tomato Salsa Beef Stock Creamy Cabbage and Bacon Soup Veal Stock Tomato Vodka Soup Curry-Spiced Carrot Soup Tomato and Rice Soup with Basil Fish Stock (Fumet) Carrot, Celery and Leek Soup with Shell!sh Stock Roasted Tomato and Pesto Soup Cornbread Dumplings Cream of Roasted Tomato Soup with Ichiban Dashi Carrot, Parsnip and Celery Root Soup soups Grilled Cheese Croutons Miso Stock with Porcini Mushrooms Vegetable Stock Cream of Roasted Turnip Soup with Baby Roasted Cauli"ower Soup with Bacon Bok Choy and Five Spices Roasted Vegetable Stock Cream of Cauli"ower Soup Mushroom Stock Zucchini Soup with Tarragon and Sun- Chestnut Soup with Tru#e Oil Dried Tomatoes Silky Cream of Corn Soup with Chipotle Zucchini Soup with Pancetta and Oven- Chilled Soups Garlic Soup with Aïoli Roasted Tomatoes Almond Gazpacho Garlic Soup with Pesto and Cabbage Cream of Zucchini