The Mbororo Problem in North West Cameroon a Historical Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Persistent High Fertility in Cameroon: Young People Recount Obstacles and Enabling Factors to Use of Contraceptives

Persistent high fertility in Cameroon: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of Contraceptives Authors: Maurice Kube 1,2,3*, Abeng Charles 2, Ndop Richard 2, Ankiah George 3 Institutions: 1 Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences University of Buea, Cameroon; 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, FMBS University of Yaounde I, Yaounde, Cameroon; 3 Department of Public Health Sciences, UBA, Bamenda, Cameroon. Background Half of the world’s population is in or entering their child bearing years. Consequently there is tremendous need for contraceptive use, especially in areas with high fertility [1]. This is particularly true in Cameroon where the persistent high fertility (6.7 children per woman) is contributing to the high maternal morbidity and mortality (435/100,000 live births) as well as the rapidly growing population (3.2%) [2-4]. By comparison, a woman in two neighboring countries Gabon and Tchad will have an average of 4.5 and 2.8 children in her lifetime respectively [5]. Maternal mortality is further increased by unintended pregnancies resulting in unsafely induced abortions [4]. High fertility and high maternal morbidity and mortality not only strain individuals, families, and public resources, but also hinder opportunities for economic development [6]. Use of contraceptives has the potential to avert unplanned births, decrease maternal morbidity and mortality, increase welfare and protect future generations [6, 7]. In 2009, 49 percent of the Cameroonian population was below 15 years and 20 percent was between the age of 15 and 24[5]. A large number of young people in Cameroon are thus in or soon reaching their reproductive age and thus have a potential risk of unplanned and unwanted pregnancy [2]. -

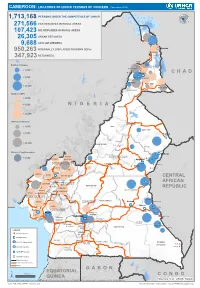

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

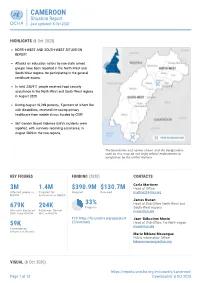

CAMEROON Situation Report Last Updated: 8 Oct 2020

CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 8 Oct 2020 HIGHLIGHTS (8 Oct 2020) NORTH-WEST AND SOUTH-WEST SITUATION REPORT Attacks on education actors by non-state armed groups have been reported in the North-West and South-West regions for participating in the general certificate exams. In total 245,911 people received food security assistance in the North-West and South-West regions in August 2020. During August 10,249 patients, 5 percent of whom live with disabilities, received life-saving primary healthcare from mobile clinics funded by CERF. 567 Gender Based Violence (GBV) incidents were reported, with survivors receiving assistance, in August 2020 in the two regions. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Carla Martinez 3M 1.4M $390.9M $130.7M Head of Office Affected people in Targeted for Required Received [email protected] NWSW assistance in NWSW ! j e r d n , A y James Nunan r r o S 33% Head of Sub-Office North-West and 679K 204K Progress South-West regions Internally displaced Returnees (former [email protected] (IDP) from NWSW IDP) in NWSW FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/9 Jean-Sébastien Munie 27/summary Head of Sub-Office, Far-North region 59K [email protected] Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria Marie Bibiane Mouangue Public information Officer [email protected] VISUAL (8 Oct 2020) https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/cameroon/ Page 1 of 13 Downloaded: 8 Oct 2020 CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 8 Oct 2020 Map of IDP, Returnees and Refugees from the North-West and South-West Regions of Cameroon Source: OCHA, UNHCR, IOM The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Assessment Report

Needs Assessment for Self-Reliance of CAR refugees in Gado, Borgop, Ngam, Mbile, Lolo and Timangolo Camps, and In Touboro Assessment Report Monitoring & Evaluation department November-December 2017 Page 1 of 30 Contents List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Key findings/executive summary .................................................................................................................. 5 Operational Context ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction: The CAR situation In Cameroon .............................................................................................. 7 Objectives ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Study Design ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Qualitative Approach ........................................................................................................................... -

The$Use$Of$New$Information$And

Advances)in)Social)Sciences)Research)Journal)–)Vol.3,)No.1) ! Publication)Date:!Jan.!25,!2016! DoI:10.14738/assrj.31.1310.! Lengha,'T.'N.'(2016).'The'Use'of'New'Information'and'Communication'Technologies'as'an'Education'Tool'in'the'Fight'Against' ! HIV/AIDS'in'Fundong,'Northwest'Region,'Cameroon.)Advances)in)Social)Sciences)Research)Journal,)3(1))51B60.' ! The$Use$of$New$Information$and$Communication*Technologies* as#an#Education#Tool#in#the#Fight#Against#HIV/AIDS%in#Fundong," Norhtwest)Region,"Cameroon) ! Tohnain)Nobert)Lengha) Department!of!Agricultural!Extension!and!Rural!Sociology,! Faculty!of!Agronomy!and!Agricultural!sciences,! University!of!Dschang,!Cameroon! ! Abstract) Fundong,) a) rural) town) found) in) the) Northwest) Region) of) Cameroon) is) located) on) latitude)10°)14’W)and)11°15’)E,)between)longitudes)6°)27’)and)8°)26’N.)))The)town)enjoys) the)privilege)of)being,)not)just)the)headquarter)of)Boyo)Division,)but)also)of)Fundong) Central) SubQDivision.) The) incidence) of) HIV/AIDS) is) critical) in) the) area) as) there) are) several)practices)like)the)scarification)of)the)body)to)apply)concoctions)common)in)the) area)which,)may)help)predispose)the)population)to)HIV/AIDS)infection.)The)affluence) that) characterise) this) small) rural) town) favours) highQrisk) behaviours,) which) expose) individuals)concerned)to)HIV/AIDS.)In)order)to)address)the)main)objective)of)the)study,) which) is) the) use) of) information) and) communication) technologies) in) the) fight) against) HIV/AIDS,) data) were) collected) at) ) the) group) -

Diversity of Plants Used to Treat Respiratory Diseases in Tubah

International Scholars Journals International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology ISSN: 2326-7267 Vol. 3 (11), pp. 001-008, November, 2012. Available online at www.internationalscholarsjournals.org © International Scholars Journals Author(s) retain the copyright of this article. Full Length Research Paper Diversity of plants used to treat respiratory diseases in Tubah, northwest region, Cameroon D. A. Focho1*, E. A. P. Nkeng2, B. A. Fonge3, A. N. Fongod3, C. N. Muh1, T. W. Ndam1 1 and A. Afegenui 1 Department of Plant Biology, University of Dschang. P. O. Box 67, Dschang, Cameroon. 2 Department of Chemistry, University of Dschang, P. O. Box 63, Dschang, Cameroon. 3 Department of Plant and Animal Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon. Accepted 17 September, 2012 This study was conducted in Tubah subdivision, Northwest region, Cameroon, aiming at identifying plants used to treat respiratory diseases. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to interview members of the population including traditional healers, herbalists, herb sellers, and other villagers. The plant parts used as well as the modes of preparation and administration were recorded. Fifty four plant species belonging to 51 genera and 33 families were collected and identified by their vernacular and scientific names. The Asteraceae was the most represented family (6 species) followed by the Malvaceae (4 species). The families Asclepiadaceae, Musaceae and Polygonaceae were represented by one species each. The plant part most frequently used to treat respiratory diseases in the study was reported as the leaf. Of the 54 plants studied, 36 have been documented as medicinal plants in Cameroon’s pharmacopoeia. However, only nine of these have been reported to be used in the treatment of respiratory diseases. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

The Dynamics and Implications of the Coffee Economy in Tubah Sub-Division, 1934-2005

International Journal of African and Asian Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2409-6938 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.38, 2017 The Dynamics and Implications of the Coffee Economy in Tubah Sub-Division, 1934-2005 Canute Ambe Ngwa Higher Teacher Training College, Bambili, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon Divine Achenui Nwenfor Department of History, University of Yaounde I, Cameroon Abstract That the coffee economy in Tubah is at a development cul-de-sac and requires an overhaul is unquestionable. The article introduces the sustainable coffee challenge and the circumstances that made the sector unsustainable and suffered a decline in Tubah. It has been argued that coffee economy in Tubah was introduced as a substitute to the legitimate trade and owed its unsustainability and eventual decline to the outbreak of the economic crisis in the 1980s. Such argument is often pegged to the grievances of the poor angry farmers who were victims of the economic crisis and appear to have written off the benefits of the coffee sector on their livelihoods in the past. Contrary to such orthodox, this paper argues that the natural environment of Tubah alongside colonial influence provided the potential for the emergence of the coffee economy. It is further illustrated that coffee cultivation and commercialization mechanisms in Tubah evolved with time and circumstances. The lack of farm subsidies and the fall in the price of the commodity in the world market left the farmers in a state of dilemma. The paper also exposes the view that the coffee economy, in spite its constraints, resulted in beneficial socio- economic mutations in Tubah. -

CMR-3W-Cash-Transfer-Partners V3.4

CAMEROON: 3W Operational Presence - Cash Programming [as of December 2016] Organizations working for cash 10 programs in Cameroon Organizations working in Organizations by Cluster Food security 5 International NGO 5 Multi-Sector cash 5 Government 2 Economic Recovery 3 Red Cross & Red /Livelihood 2 Crescent Movement Nutrition 1 UN Agency 1 WASH 1 Number of organizations Multi-Sector Cash by departments 15 5 distinct organizations 9 organizations conducting only emergency programs 1 organizations conducting only regular programs Number of organizations by departments 15 Economic Recovery/Livelihood Food security 3 distinct organizations 5 distinct organizations Number of organizations Number of organizations by department by department 15 15 Nutrition WASH 3 distinct organizations 1 organization Number of organizations Number of organizations by department by department 15 15 Creation: December 2016 Sources: Cash Working group, UNOCHA and NGOs More information: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/cash )HHGEDFNRFKDFDPHURRQ#XQRUJ 7KHERXQGDULHVDQGQDPHVVKRZQDQGWKHGHVLJQDWLRQVXVHGRQWKLVPDSGRQRWLPSO\RI̙FLDOHQGRUVHPHQWRUDFFHSWDQFHE\WKH8QLWHG1DWLRQV CAMEROON:CAMEROON: 3W Operational Presence - Cash Programming [as of December 2016] ADAMAOUA FAR NORTH NORTH 4 distinct organizations 9 distinct organizations 1 organization DJEREM DIAMARE FARO MINJEC CRF MINEPAT CRS IRC MAYO-BANYO LOGONE-ET-CHARI MAYO-LOUTI MINEPAT MINEPAT WFP, PLAN CICR MMBERE MAYO-REY PLAN PUI MINEPAT CENTRE MAYO-DANAY 1 organization MINEPAT LITTORAL 1 organization -

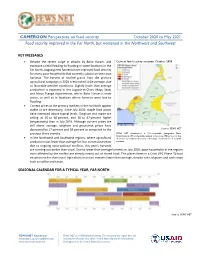

CAMEROON Perspectives on Food Security October 2020 to May 2021 Food Security Improved in the Far North, but Worsened in the Northwest and Southwest

CAMEROON Perspectives on food security October 2020 to May 2021 Food security improved in the Far North, but worsened in the Northwest and Southwest KEY MESSAGES • Despite the recent surge in attacks by Boko Haram, and Current food security situation, October 2020 excessive rainfall leading to flooding in some locations in the Far North, ongoing new harvests have improved food security for many poor households that currently subsist on their own harvests. The harvest of rainfed grains from the primary agricultural campaign in 2020 is estimated to be average, due to favorable weather conditions. Slightly lower than average production is expected in the Logone-et-Chari, Mayo Sava, and Mayo Tsanga departments, where Boko Haram is most active, as well as in locations where harvests were lost to flooding. • Current prices at the primary markets in the Far North appear stable or are decreasing. Since July 2020, staple food prices have increased above typical levels. Sorghum and maize are selling at 46 to 60 percent, and 30 to 47 percent higher (respectively) than in July 2019. Although current prices are still above average, sorghum and groundnut prices have decreased by 17 percent and 18 percent as compared to the Source: FEWS NET previous three months. FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible (Integrated Phase Classification). IPC-compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but • In the Northwest and Southwest regions, where agricultural does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national food security production was lower than average for four consecutive years partners. due to ongoing socio-political conflicts, this year's harvests are running out earlier than usual. -

Cameroon July 2019

FACTSHEET Cameroon July 2019 Cameroon currently has On 25 July, UNHCR organized a A US Congress delegation 1,548,652 people of concern, preparatory workshop in visited UNHCR in Yaoundé on 01 including 287,467 Central Bertoua ahead of cross-border July and had an exchange with African and 107,840 Nigerian meeting on voluntary refugees and humanitarian actors refugees. repatriation of CAR refugees. on situation in the country. POPULATION OF CONCERN (1,548,652 AS OF 30 JULY) CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 266,810 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 105,923 URBAN REFUGEES** 25,938 ASYLUM SEEKERS*** 8,972 IDPs FAR NORTH**** 262,831 IDPs NORTH-WEST/SOUTH-WEST***** 530,806 RETURNEES**** 347,372 **Incl. 20,657 Central Africans and 1,917 Nigerian refugees living in urban areas. ***Incl. 6,917 Central Africans and 42 Nigerian asylum seekers living in urban areas. **** Source: IOM DTM #18. Including 237,349 estimated returnees in NW/SW regions. *****IDPs in Littoral, North-West, South-West and West regions, Source: OCHA. FUNDING (AS OF 30 JULY) USD 90.3 M Requested for Cameroon Gap: 86% Gap: 74% UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 251 167 National Staff 42 International Staff 42 Affiliate workforce (8 International and 34 National) 11 OFFICES: Representation – Yaounde Sub Offices – Bertoua, Meiganga, Maroua, Buea Field Offices – Batouri, Djohong, Touboro, Douala and Bamenda. Field Unit – Kousseri Refugees from Cameroon and UNHCR staff on a training visit to Songhai Farming Complex, Porto Novo-Benin www.unhcr.org 1 FACTSHEET > Cameroon – July 2019 WORKING WITH PARTNERS UNHCR coordinates protection and assistance for persons of concern in collaboration with: Government Partners: Ministries of External Relations, Territorial Administration, Economy, Planning and Regional Development, Public Health, Women’s Empowerment and the Family, Social Affairs, Justice, Basic Education, Water and Energy, Youth and Civic Education, the National Employment Fund and others, Secrétariat Technique des Organes de Gestion du Statut des réfugiés. -

Cameroon:NW/SW Highlights Needs 690K 414K 63K1 52 $9.5M

Cameroon:NW/SW WASH Update April 2020 Hand washing sensitization of community members in the North West region. Photo by NRC Highlights Needs In order to contain the spread of COVID-19, WASH partners have scaled up community 690k People in need of WASH engagement activities. More than 116,000 services in NW/SW people were reached through COVID 19 sensitization sessions in April. 414k In response to the COVID 19 pandemic, Targeted ReachOut, with support from UNICEF, 1 installed 250 communal hand washing 63k IDPs & Returnees stations in Ekondo Titi. More than 12,500 people are expected to benefit. 52 More than 10,000 individuals received WASH partners WASH and hygiene kits from WASH partners in April. $9.5m In April, about 1,600 people benefitted from required for WASH improved water supply as a result of US$9.5M installation of water distribution systems by WASH partners. Reguired WASH partners provided improved sanitation facilities to 400 people. US$0.2M Funded 1 IDP Tracking Database, May 2020 (Note: This figure is the latest displacement figure as of 16 May 2020) Website: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/water-sanitation-hygiene For more information contact Wash Cluster Coordinator: Nchunguye Festo Vyagusa Email: [email protected] WATER Plan International, in collaboration with UNICEF completed rehabilitation of a water distribution system in Fundong, Boyo division, reaching 1,650 individuals with safe drinking water. Rehabilitation of water systems in Bamenda 2 subdivision in Mezam is ongoing. Plan International, supported by UNICEF is planning to rehabilitate two water distribution systems in Babessi sub-division of Ngo- Ketunjia division in May.