2021 Preventive Health Guidelines for Members 65 Years of Age and Older

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geriatric Medicine and Why We Need Geriatricians! by Juergen H

Geriatric Medicine and why we need Geriatricians! by Juergen H. A. Bludau, MD hat is geriatric medicine? Why is there a need for 1. Heterogeneity: As people age, they become more Wthis specialty? How does it differ from general heterogeneous, meaning that they become more and more internal medicine? What do geriatricians do differently when different, sometimes strikingly so, with respect to their they evaluate and treat an older adult? These are common health and medical needs. Imagine for a moment a group questions among patients and physicians alike. Many of 10 men and women, all 40 years old. It is probably safe internists and family practitioners argue, not unjustifiably, to say that most, if not all, have no chronic diseases, do not that they have experience in treating and caring for older see their physicians on a regular basis, and take no long- patients, especially since older adults make up almost half of term prescription medications. From a medical point of all doctors visits. So do we really need another type of view, this means that they are all very similar. Compare this physician to care for older adults? It is true that geriatricians to a group of 10 patients who are 80 years old. Most likely, may not necessarily treat older patients differently per se. But you will find an amazingly fit and active gentleman who there is a very large and important difference in that the focus may not be taking any prescription medications. On the of the treatment is different. In order to appreciate how other end of the spectrum, you may find a frail, memory- significant this is, we need to look at what makes an older impaired, and wheelchair-bound woman who lives in a adult different from a younger patient. -

Fundamentals of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 2Nd Edition

PART 1 Social, Ethical, and Economic Issues of Aging 1 Challenges in Geriatric Care REBECCA B. SLEEPER Learning Objectives 1. Evaluate the applicability of clinical literature to the elderly patient using an approach that is tailored to specific subgroups of the geriatric population. 2. Differentiate the roles of healthcare professionals and the various services and venues available in the care of geriatric patients. 3. Infer scenarios in which geriatric patients are at risk for suboptimal care and intervene when breakdowns in the continuum of care are identified. 4. Recognize the impact of caregiver burden on patient outcomes. Key Terms and Definitions ASSISTED LIVING FACILITY: Living environment that provides added services to the individual who is safe to live in the community environment but requires some assistance with various daily activities. CAREGIVER BURDEN: Psychosocial and physical stress experienced by an individual who provides care to another person. CERTIFIED GERIATRIC PHARMACIST: Pharmacist who has achieved certification from the Commission for Certification in Geriatric Pharmacy. CERTIFIED NURSE’S ASSISTANT: Individual who has earned a certificate to practice as a nurse’s assistant and who may work in a wide variety of healthcare settings ranging from long-term care facilities to private homes. GERIATRIC: Adjective generally used to refer to an older individual. GERIATRICIAN: Physician with expertise, as demonstrated by fellowship or other added qualifications, in the care of older persons. GERONTOLOGICAL NURSE: Nurse with expertise, as demonstrated by exam or other added qualifications, in the care of older persons. 4 | Fundamentals of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy INFORMAL CAREGIVER: An individual who does not have formal training as a healthcare professional but who provides daily care to another individual; usually unpaid. -

Partnership for Health in Aging

Partnership FOR HealthiN Aging Multidisciplinary Competencies in the Care of Older Adults at the Completion of the Entry-level Health Professional Degree Preface In June 2008, the American Geriatrics Society convened a A workgroup of healthcare professionals with experience meeting of 21 organizations representing healthcare pro- in competency development, certification, and accredita- fessionals who care for older adults to discuss how these tion was convened in February 2009. Workgroup mem- organizations could work together to: bers represent ten healthcare disciplines: • advance recommendations from the 2008 Institute • Dentistry of Medicine Report, Retooling for an Aging America: • Medicine Building the Health Care Workforce, and • Nursing • advocate for ways to meet the healthcare needs of the • Nutrition nation’s rapidly growing older population. • Occupational Therapy This meeting led to the development of a loose coalition – • Pharmacy the Partnership for Health in Aging (PHA) – that identi- • Physical Therapy fied as its first step the development of a set of core com- • Physician Assistants petencies in the care of older adults that are relevant to and • Psychology can be endorsed by all health professional disciplines. • Social Work The workgroup began with a comprehensive matrix of The workgroup reviewed all comments received, and competencies across these ten disciplines. (Note: These developed the final set of competencies on the following disciplines are currently at different stages in developing page. The set describes essential skills that healthcare discipline-specific geriatrics competencies). Through an professionals in the above ten disciplines should have, iterative process, the workgroup drafted a set of baseline and necessary approaches they should master, by the time competencies that were circulated among more than they complete their entry-level degree, in order to provide 25 professional organizations for review and comment. -

GERIATRIC MEDICINE What Is Geriatric Medicine?

GERIATRIC MEDICINE What is Geriatric Medicine? Geriatrics is the branch of medicine that focuses on health promotion, prevention, and diagnosis and treatment of disease and disability in older adults. In recent surveys, geriatricians are among the most satisfied physicians in terms of their choice of specialty. Geriatrics offers a wide diversity of career options and is a clinically and intellectually rewarding discipline given the medical complexity of older adults. Geriatricians reap the rewards of making a difference in a patient’s level of independence, well- being and quality of life. With the rapid growth of the older population in the United States, there is a pressing demand for physicians with specialized training in geriatrics. ama-assn.org/specialty/geriatric-medicine The Birth of “Geriatric” Medicine • In 1909, Austrian born physician, Ignatz Leo Nascher coined the term “geriatrics” for care of the elderly, explaining, “Geriatrics, from geras, old age, and iatrikos, relating to the physician, is a term I would suggest as an addition to our vocabulary, to cover the same field in old age that is covered by the term pediatrics in childhood, to emphasize the necessity of considering senility and its disease apart from maturity and to assign it a separate place in medicine.” • Until Nascher’s time, older adults were not treated differently or in different ways than other adult patients. Social forces came into play in the period during WWI and WWII that both necessitated and facilitated long-term care for the elderly: The number of elderly people began to increase due to improvements in economic conditions and medicine. -

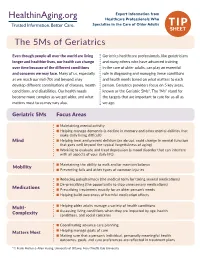

The 5Ms of Geriatrics

Expert Information from Healthcare Professionals Who Specialize in the Care of Older Adults TIP SHEET The 5Ms of Geriatrics Even though people all over the world are living Geriatrics healthcare professionals, like geriatricians longer and healthier lives, our health can change and many others who have advanced training over time because of the different conditions in the care of older adults, can play an essential and concerns we may face. Many of us, especially role in diagnosing and managing these conditions as we reach our mid-70s and beyond, may and health needs based on what matters to each develop different combinations of diseases, health person. Geriatrics providers focus on 5 key areas, conditions, and disabilities. Our health needs known as the Geriatric 5Ms*. The “Ms” stand for become more complex as we get older, and what the targets that are important to care for us all as matters most to us may vary also. we age. Geriatric 5Ms Focus Areas n Maintaining mental activity n Helping manage dementia (a decline in memory and other mental abilities that make daily living difficult) Mind n Helping treat and prevent delirium (an abrupt, rapid change in mental function that goes well beyond the typical forgetfulness of aging) n Working to evaluate and treat depression (a mood disorder that can interfere with all aspects of your daily life) n Maintaining the ability to walk and/or maintain balance Mobility n Preventing falls and other types of common injuries n Reducing polypharmacy (the medical term for taking several medications) -

Glossary of Commonly Used Health Care Terms and Acronyms

GLOSSARY OF COMMONLY USED HEALTH CARE TERMS AND ACRONYMS Vermont Health Care Resources 1 Health Care Terms A and dividends, as well as conducted other statistical studies. academic medical center A group of acute care Medical treatment rendered to related institutions including a teaching individuals whose illnesses or health hospital or hospitals, a medical school and problems are of short-term or episodic its affiliated faculty practice plan, and other nature. Acute care facilities are those health professional schools. hospitals that mainly serve persons with short-term health problems. access An individual’s ability to obtain appropriate health care services. Barriers to acute disease A disease characterized by a access can be financial (insufficient single episode of a relatively short duration monetary resources), geographic (distance to from which the patient returns to his/her providers), organizational (lack of available normal or pervious state of level of activity. providers) and sociological (e.g., While acute diseases are frequently discrimination, language barriers). Efforts to distinguished from chronic diseases, there is improve access often focus on no standard definition or distinction. It is providing/improving health coverage. worth noting that an acute episode of a chronic disease (for example, an episode of accident insurance A policy that provides diabetic coma in a patient with diabetes) is benefits for injury or sickness directly often treated as an acute disease. resulting from an accident. adjusted average per capita cost accreditation A process whereby a program (AAPCC) The basis for HMO or CMP of study or an institution is recognized by an (Competitive Medical Plan) reimbursement external body as meeting certain under Medicare-risk contracts. -

Preventive Geriatrics

International Journal of Biotechnology and Biomedical Sciences p-ISSN 2454-4582, e-ISSN 2454-7808, Volume 4, Issue 2; July-December, 2018 pp. 90-93 © Krishi Sanskriti Publications http://www.krishisanskriti.org/Publication.html Preventive Geriatrics Aditi Singh Vasant Valley School, Vasant Kunj New Delhi-110070 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—This paper addresses the common diseases and issues The process of ageing cannot be prevented; however, some of that affect the elderly and disease prevention strategies with regard the effects can be inhibited and slowed down. to the elderly. India comprises of 35.5% elderly population. A major portion includes individuals with respiratory and neurological In order to do so, several methods have been designed. These diseases namely bronchitis, asthma, stroke among others. This paper methods include leading a healthy lifestyle, medication, also delves into Preventive geriatrics which includes methods vaccination and physical therapy. ranging from vaccination to early detection of disease leading to proper treatment or significant aid to prevent the onset of disease. Vaccination is the process of administering a vaccine, which is Analysis of the aforementioned issues aids in understanding the ideal made of an inoculated or heat-killed bacterium in order to method to reduce morbidity in Indian Elderly population. prevent the body from several diseases. Types of vaccinations include influenza, pneumococcal and tetanus among others. Keywords: Disease Prevention, Vaccination for Elderly, Geriatrics, Morbidity in Elderly, Mortality. However, the pertinent question regarding Vaccination is the effectiveness of this method and the proportion of individuals MATERIALS AND METHODS that receive it. The ratio of the elderly who receive the vaccine This study was carried out by interacting with several elderly to those who do not is symbolic of the divide between urban individuals dwelling in my neighborhood and close by areas. -

Geriatrician Roles and the Value of Geriatrics in an Evolving Healthcare System

UCSF Health Workforce Research Center on Long-Term Care Resear ch Repor t Geriatrician Roles and the Value of Geriatrics in an Evolving Healthcare System Tim othy Bates, MPP Aubri Kottek, MPH Joanne Spet z, PhD July 8, 2019 This report was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $533,932.00, with 0% financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, HRSA, HHS, or the US Governm ent. Please cit e as: Bates, T., Kottek, A., Spetz, J. (2019). Geriatrician Roles and the Value of Geriatrics in an Evolving Healthcare System. San Francisco, CA: UCSF Health Workforce Research Center on Long- Term Care. UCSF Health Workforce Research Center on Long-Term Care, 3333 California Street, Suite 265, San Fr ancisco, CA, 94118 Copyright © 2019 The Regents of the University of California Cont act : Tim Bates, [email protected], (415) 502-1558 UCSF Health Workforce Research Center on Long-Term Care Research Report Geriatrician Roles and the Value of Geriatrics in an Evolving Healthcare System Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................... 2 Table of Tables .............................................................................................. 3 Execut ive Sum m ary ...................................................................................... -

Nephrology/Geriatrics III Panel

Nephrology/Geriatrics III Panel Series Editors: Falls in the Older Adult Betty J. Dong, Pharm.D., FCCP, FASHP, FAPHA, AAHIVP Authors Professor of Clinical Pharmacy and Family and Community Medicine Crystal Burkhardt, Pharm.D., MBA, BCPS, BCGP University of California Schools of Pharmacy and Medicine Clinical Associate Professor San Francisco, California Department of Pharmacy Practice David P. Elliott, Pharm.D., FCCP, FASCP, AGSF, BCGP School of Pharmacy University of Kansas Professor and Associate Chair for the Charleston Campus Kansas City, Kansas Department of Clinical Pharmacy West Virginia University School of Pharmacy Stephanie M. Crist, Pharm.D., BCACP, BCGP Charleston, West Virginia Assistant Professor Department of Pharmacy Practice Faculty Panel Chair: Division of Ambulatory Care Emily R. Hajjar, Pharm.D., MS, BCPS, BCACP, BCGP St. Louis College of Pharmacy Associate Professor Clinical Pharmacist Specialist, Geriatrics Jefferson College of Pharmacy Department of Care Management Thomas Jefferson University Mercy Clinic East Communities Philadelphia, Pennsylvania St. Louis, Missouri Reviewers Neurocognitive Disorders Heather Sakely, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCGP Director, PGY2 Geriatric Pharmacy Residency Authors Director, Geriatric Pharmacotherapy Christine Eisenhower, Pharm.D., BCPS Department of Medical Education Clinical Associate Professor UPMC St. Margaret Department of Pharmacy Practice Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy Elizabeth A. Koczera, Pharm.D., BCACP Kingston, Rhode Island Ambulatory Care -

A Geriatric Anesthesiology Curriculum

A Geriatric Anesthesiology Curriculum A Geriatric Anesthesiology Curriculum was created through the collaborative efforts of the members of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Geriatric Anesthesia and the Society for the Advancement of Geriatric Anesthesiology (SAGA). It was developed in cooperation with the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) and supported through the AGS/John A. Hartford Foundation of New York City Project: Increasing Geriatrics Expertise in Surgical and Related Medical Specialties. Editors: • Sheila R. Barnett, MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School • Christopher J. Jankowski, MD; Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN • Shamsuddin Ahktar, MD; Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT Contributors: • Ruma Bose, MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School • Deborah J. Culley, MD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School • Leanne Groban, MD; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, NC • Michael C. Lewis, MD; Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami • Terri G. Monk, MD, MS; Duke University Medical Center, NC • G. Alec Rooke, MD, PhD; Beth Israel Medical Center, Harvard Medical School & University of Washington, Seattle • Frederick E. Sieber, MD; Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, MD • Jeffrey H. Silverstein, MD; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY • Mary Ann Vann, MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School • Zhongcong Xie, MD, PhD; Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School • Resident participant: Kai Matthes, MD, PhD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School Created and approved by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Committee on Geriatric Anesthesia: October 14th 2007 - 1 - A Geriatric Anesthesiology Curriculum Table of Contents BACKGROUND 1. -

Age Associated Issues: Geriatrics A.D

Anesthesiology Clin N Am 22 (2004) 45–58 Age associated issues: geriatrics A.D. John, MDa,b,*, Frederick E. Sieber, MDa,b aDepartment of Anesthesiology, The Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 4940 Eastern Avenue, Building A-Room 387, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA bDivision of Anesthesia and Critical Care Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA As the population ages there will be an ever-increasing number of elderly patients who will require surgical care (Fig. 1). The estimated species-specific life span for human beings is approximately 110 years. The point of reference for the definition of being elderly is taken as an age greater than 65 years. Murvachick [1] further subdivides this group into: elderly (ages: 65–74), aged (ages: 75–84), and the very old (ages 85 and above). Currently patients aged 65 and above comprise at least one quarter of the surgical population and one quarter to one half of the ICU admissions [1,2]. How to best optimize the care that an elderly patient re- ceives is a fundamental problem that has enormous financial, social, and medi- cal implications. The difference between physiologic and biologic age, and the complexity and the heterogeneity of the range of response in the elderly is exemplified by the following case. An 87-year-old woman who has a past medical history significant for hypertension, for which she takes atenolol, fell while rushing to answer her doorbell. This 87-year-old patient is pleasant, sprightly, and neurologically intact. She lives alone at home and takes care of herself. -

Educational Goals & Objectives the Geriatrics Rotation Will Provide The

Educational Goals & Objectives The Geriatrics rotation will provide the resident with an opportunity to become skilled in the prevention, evaluation, and management of conditions unique to the elderly. This rotation is based in the nursing home, with a focus on experiential learning through the supervised management of patients residing in a geriatric facility. Residents will learn to recognize how disease manifests differently in the elderly and become familiar with a subset of issues in cardiovascular medicine, geropsychiatry, neurology, nutrition, and general internal medicine pertinent to the care of geriatric patients. While the nursing home does not offer a venue for experiencing all issues addressed in geriatric medicine, it provides exposure to many common conditions and a starting point to facilitate discussion and learning on other pertinent topics. Depth of exposure should be such that residents can develop competency in disease prevention, management of common diseases, addressing obstacles to maintaining functional independence, and appropriate indications for referral to a geriatrician. Faculty will facilitate learning in the 6 core competencies as follows: Patient Care and Procedural Skills I. All residents must be able to provide compassionate, culturally-sensitive care for geriatric patients. R2s should seek directed and appropriate specialty consultation when necessary to further patient care. R3s should be able to coordinate input from multiple consultants and manage conflicting recommendations. II. R1s will demonstrate the ability to take a complete medical history, with particular attention to functional status, social history, immunizations, and medications. R2s should be able to collect additional historical information from electronic and/or outside records, elicit a more thorough history, and recognize evidence of physical abuse or neglect.