Geriatrician Roles and the Value of Geriatrics in an Evolving Healthcare System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geriatric Medicine and Why We Need Geriatricians! by Juergen H

Geriatric Medicine and why we need Geriatricians! by Juergen H. A. Bludau, MD hat is geriatric medicine? Why is there a need for 1. Heterogeneity: As people age, they become more Wthis specialty? How does it differ from general heterogeneous, meaning that they become more and more internal medicine? What do geriatricians do differently when different, sometimes strikingly so, with respect to their they evaluate and treat an older adult? These are common health and medical needs. Imagine for a moment a group questions among patients and physicians alike. Many of 10 men and women, all 40 years old. It is probably safe internists and family practitioners argue, not unjustifiably, to say that most, if not all, have no chronic diseases, do not that they have experience in treating and caring for older see their physicians on a regular basis, and take no long- patients, especially since older adults make up almost half of term prescription medications. From a medical point of all doctors visits. So do we really need another type of view, this means that they are all very similar. Compare this physician to care for older adults? It is true that geriatricians to a group of 10 patients who are 80 years old. Most likely, may not necessarily treat older patients differently per se. But you will find an amazingly fit and active gentleman who there is a very large and important difference in that the focus may not be taking any prescription medications. On the of the treatment is different. In order to appreciate how other end of the spectrum, you may find a frail, memory- significant this is, we need to look at what makes an older impaired, and wheelchair-bound woman who lives in a adult different from a younger patient. -

A Crisis in Health Care: a Call to Action on Physician Burnout

A CRISIS IN HEALTH CARE: A CALL TO ACTION ON PHYSICIAN BURNOUT Partnership with the Massachusetts Medical Society, Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Harvard Global Health Institute A Crisis in Health Care: A Call to Action on Physician Burnout Authors About the Massachusetts Medical Society Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH The Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) is the state- Director, Harvard Global Health Institute wide professional association for physicians and medical stu- Senior Associate Dean for Research Translation and dents, supporting 25,000 members. The MMS is dedicated Global Strategy to educating and advocating for the physicians and patients K.T. Li Professor, Dept. of Health Policy and Management, of Massachusetts both locally and nationally. As a voice of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health leadership in health care, the MMS provides physician and Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School patient perspectives to influence health-related legislation Andrew R. Iliff, MA, JD at both state and federal levels, works in support of public Lead Writer and Program Manager, Harvard Global health, provides expert advice on physician practice manage- Health Institute ment, and addresses issues of physician well-being. Alain A. Chaoui, MD, FAAFP About the Massachusetts Health and President, Massachusetts Medical Society Hospital Association Steven Defossez, MD, EMHL The Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association Vice President, Clinical Integration, Massachusetts Health (MHA) was founded in 1936, and its members include and Hospital Association 71 licensed member hospitals, many of which are organized Maryanne C. Bombaugh, MD, MSc, MBA within 29 member health systems, as well as interested indi- President-Elect, Massachusetts Medical Society viduals and other healthcare stakeholders. -

Guidelines for Developing a Team Physician Services Agreement in the Secondary School

Guidelines for Developing a Team Physician Services Agreement in the Secondary School The following document has been developed by the NATA Secondary School Athletic Trainers’ Committee in an effort to assist secondary school athletic trainers in strengthening and formalizing the relationship with a team physician. The included components for such an agreement have been suggested by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and NATA (see resources). Guidelines for Developing a Team Physician Agreement in the Secondary School is intended to serve as an overview of those key components as they apply to the secondary school setting. It should be noted that while all components cited have merit, not all may be practical for all situations. Variability with state and local regulations must also be considered. DEVELOPED BY THE SECONDARY SCHOOL ATHLETIC TRAINERS’ COMMITTEE: Larry Cooper, MS, ATC, LAT, Chair Kembra Mathis, MEd, ATC, LAT Bart Peterson, MSS, ATC, Incoming Chair Lisa Walker, ATC Denise Alosa, MS, ATC Stacey Ritter, MS, ATC Casey Christy, ATC Chris Snoddy, ATC, LAT George Wham, EdD, ATC, SCAT Chris Dean, ATC Dale Grooms, ATC Cari Wood, ATC, NATA BOD Liaison Dan Newman, MS, ATC, LAT Amanda Muscatell, NATA Staff Liaison A SPECIAL THANKS TO TEAM PHSYICIAN SERVICES AGREEMENT SUBCOMMITTEE: George Wham, EdD, ATC, SCAT Dale Grooms, ATC Casey Christy, ATC Larry Cooper, MS, ATC, LAT, Chair Bart Peterson, MSS, ATC, Incoming Chair NATA Secondary School Athletic Trainers’ Committee 2016 Disclaimer: The materials and information provided in the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (“NATA”) “Guidelines for Developing a Team Physician Services Agreement in the Secondary School” (the “Guideline”) are educational in nature, and the Guideline is published as a resource for NATA members and is intended solely for personal use/reference in the manner described herein. -

White and Brown Bagging Emerging Practices, Emerging Regulation

White and Brown Bagging Emerging Practices, Emerging Regulation Prepared By The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy White and Brown Bagging Emerging Practices, Emerging Regulation Published April 2018 Copyright 2018 National Association of Boards of Pharmacy 1600 Feehanville Drive Mount Prospect, IL 60056 USA 847/391‐4406 www.nabp.pharmacy Carmen A. Catizone, MS, RPh, DPh Executive Director/Secretary NABP Mission Statement NABP is the independent, international, and impartial Association that assists its member boards and jurisdictions for the purpose of protecting the public health. NABP Vision Statement Innovating and collaborating today for a safer public health tomorrow. ________________________________________________________________________ © 2018 by the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the executive director/secretary of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. The terms “National Association of Boards of Pharmacy,” and “NABP,” are registered trademarks of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Violation of the copyright will lead to prosecution under federal copyright laws. Table of Contents Overview……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Results ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Results Background …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 References ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 -

Practitioner Acronym Table

Practitioner Acronym Table AAP American Academy of Pediatrics ABAI American Board of Allergy and Immunology ABFP American Board of Family Practitioners ABO American Board of Otolaryngology ABPN American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology AK Acupuncturist (Pennsylvania) AOBFP American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians American Osteopathic Board of Special Proficiency in Osteopathic Manipulative AOBSPOMM Medicine AP Acupuncture Physician ASG Affiliated Study Group BHMS Bachelor of Homeopathic Medicine and Surgery BSN Bachelor of Science, Nursing BVScAH Bachelor of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry CA Certified Acupuncturist CAAPM Clinical Associate of the American Academy of Pain Management CAC Certified Animal Chiropractor CCH Certified in Classical Homeopathy CCSP Certified Chiropractic Sports Physician CRNP Certified Registered Nurse Practitioner CRRN Certified Rehabilitation Registered Nurse CSPOMM Certified Specialty of Proficiency in Osteopathic Manipulation Medicine CVA Certified Veterinary Acupuncturist DAAPM Diplomate of American Academy of Pain Management DABFP Diplomate of the American Board of Family Practice DABIM Diplomate of the American Board of Internal Medicine DAc Diplomate in Acupuncture DAc (RI) Doctor of Acupuncture, Rhode Island DAc (WV) Doctor of Acupuncture, West Virginia DACBN Diplomate of American Chiropractic Board of Nutrition DACVD Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Dermatology DC Doctor of Chiropractic DDS Doctor of Dentistry DHANP Diplomate of the Homeopathic Academy of Naturopathic -

Team Physician Consensus Statement

Team Physician Consensus Statement SUMMARY QUALIFICATIONS OF A TEAM PHYSICIAN The objective of the Team Physician Consensus Statement is to provide The primary concern of the team physician is to provide physicians, school administrators, team owners, the general public, and the best medical care for athletes at all levels of participa- individuals who are responsible for making decisions regarding the medical tion. To this end, the following qualifications are necessary care of athletes and teams with guidelines for choosing a qualified team physician and an outline of the duties expected of a team physician. for all team physicians: Ultimately, by educating decision makers about the need for a qualified • Have an M.D. or D.O. in good standing, with an team physician, the goal is to ensure that athletes and teams are provided unrestricted license to practice medicine the very best medical care. • The Consensus Statement was developed by the collaboration of six Possess a fundamental knowledge of emergency care major professional associations concerned about clinical sports medicine regarding sporting events issues: American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of • Be trained in CPR Orthopaedic Surgeons, American College of Sports Medicine, American • Have a working knowledge of trauma, musculoskeletal Medical Society for Sports Medicine, American Orthopaedic Society for injuries, and medical conditions affecting the athlete Sports Medicine, and the American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Med- icine. These organizations have committed to forming an ongoing project- In addition, it is desirable for team physicians to have based alliance to “bring together sports medicine organizations to best clinical training/experience and administrative skills in serve active people and athletes.” some or all of the following: • Specialty Board certification EXPERT PANEL • Continuing medical education in sports medicine • Formal training in sports medicine (fellowship train- Stanley A. -

Fundamentals of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 2Nd Edition

PART 1 Social, Ethical, and Economic Issues of Aging 1 Challenges in Geriatric Care REBECCA B. SLEEPER Learning Objectives 1. Evaluate the applicability of clinical literature to the elderly patient using an approach that is tailored to specific subgroups of the geriatric population. 2. Differentiate the roles of healthcare professionals and the various services and venues available in the care of geriatric patients. 3. Infer scenarios in which geriatric patients are at risk for suboptimal care and intervene when breakdowns in the continuum of care are identified. 4. Recognize the impact of caregiver burden on patient outcomes. Key Terms and Definitions ASSISTED LIVING FACILITY: Living environment that provides added services to the individual who is safe to live in the community environment but requires some assistance with various daily activities. CAREGIVER BURDEN: Psychosocial and physical stress experienced by an individual who provides care to another person. CERTIFIED GERIATRIC PHARMACIST: Pharmacist who has achieved certification from the Commission for Certification in Geriatric Pharmacy. CERTIFIED NURSE’S ASSISTANT: Individual who has earned a certificate to practice as a nurse’s assistant and who may work in a wide variety of healthcare settings ranging from long-term care facilities to private homes. GERIATRIC: Adjective generally used to refer to an older individual. GERIATRICIAN: Physician with expertise, as demonstrated by fellowship or other added qualifications, in the care of older persons. GERONTOLOGICAL NURSE: Nurse with expertise, as demonstrated by exam or other added qualifications, in the care of older persons. 4 | Fundamentals of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy INFORMAL CAREGIVER: An individual who does not have formal training as a healthcare professional but who provides daily care to another individual; usually unpaid. -

Structuring Physician-Pharmacy Ventures

Presenting a live 90-minute webinar with interactive Q&A Structuring Physician-Pharmacy Ventures: Minimizing Regulatory Risks, Ensuring Reimbursement Navigating Corporate Practice of Medicine/Pharmacy, Anti-Kickback and Stark Laws, and State Regulation WEDNESDAY, MAY 3, 2017 1pm Eastern | 12pm Central | 11am Mountain | 10am Pacific Today’s faculty features: Reesa N. Handelsman, Partner, Wachler & Associates, Royal Oak, Mich. Rick L. Hindmand, Member, McDonald Hopkins, Chicago Todd A. Nova, Shareholder, Hall Render Killian Heath & Lyman, Milwaukee The audio portion of the conference may be accessed via the telephone or by using your computer's speakers. Please refer to the instructions emailed to registrants for additional information. If you have any questions, please contact Customer Service at 1-800-926-7926 ext. 10. Tips for Optimal Quality FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY Sound Quality If you are listening via your computer speakers, please note that the quality of your sound will vary depending on the speed and quality of your internet connection. If the sound quality is not satisfactory, you may listen via the phone: dial 1-866-819-0113 and enter your PIN when prompted. Otherwise, please send us a chat or e-mail [email protected] immediately so we can address the problem. If you dialed in and have any difficulties during the call, press *0 for assistance. Viewing Quality To maximize your screen, press the F11 key on your keyboard. To exit full screen, press the F11 key again. Continuing Education Credits FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY In order for us to process your continuing education credit, you must confirm your participation in this webinar by completing and submitting the Attendance Affirmation/Evaluation after the webinar. -

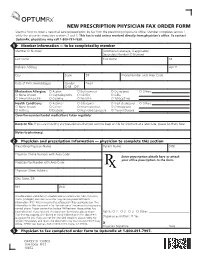

NEW PRESCRIPTION PHYSICIAN FAX ORDER FORM Use This Form to Order a New Mail Service Prescription by Fax from the Prescribing Physician’S Office

NEW PRESCRIPTION PHYSICIAN FAX ORDER FORM Use this form to order a new mail service prescription by fax from the prescribing physician’s office. Member completes section 1, while the physician completes sections 2 and 3. This fax is void unless received directly from physician’s office. To contact OptumRx, physicians may call 1-800-791-7658. 1 Member information — to be completed by member Member ID Number (Additional coverage, if applicable) Secondary Member ID Number Last Name First Name MI Delivery Address Apt. # City State ZIP Phone Number with Area Code Date of Birth (mm/dd/yyyy) Gender Email { M { F Medication Allergies: { Aspirin { Erythromycin { Quinolones { Others: { None known { Cephalosporins { NSAIDs { Sulfa { Amoxil/Ampicillin { Codeine { Penicillin { Tetracyclines Health Conditions: { Asthma { Glaucoma { High cholesterol { Others: { None known { Cancer { Heart condition { Osteoporosis { Arthritis { Diabetes { High blood pressure { Thyroid Disease Over-the-counter/herbal medications taken regularly: Keep on file. If you are including any prescriptions that you want to keep on file for shipment at a later date, please list them here: Notes to pharmacy: 2 Physician and prescription information — physician to complete this section Prescribing Physician Name Patient Name DOB Physician Phone Number with Area Code Enter prescription details here or attach your office prescription to the form. Physician Fax Number with Area Code Physician Street Address City, State, ZIP NPI DEA This document and others if attached contain information from OptumRx that is privileged, confidential and/or may contain protected health information (PHI). We are required to safeguard PHI by applicable law. The information in this document is for the sole use of the person(s) or company named above. -

Changes to the Reimbursement for Physician Pathology, Medicine and Surgical Services with a Professional (26) and Technical (TC) Component

Connecticut Medical Assistance Program Provider Bulletin 2015-62 Policy Transmittal 2015-28 August 2015 Effective Date: September 7, 2015 Roderick L. Bremby, Commissioner Contact: Nina Holmes @ 860-424-5486 TO: Physicians, Physician Assistants, Advanced Practice Registered Nurses, Certified Nurse Midwives, Optometrists, and Podiatrists RE: Changes to the Reimbursement for Physician Pathology, Medicine and Surgical Services with a Professional (26) and Technical (TC) Component This policy transmittal is being sent to notify providers Accessing the Fee Schedules that, effective for dates of service September 7, 2015 Fee schedules can be accessed and downloaded by and forward, the Department of Social Services is going to the Connecticut Medical Assistance Web site: revising the reimbursement for the professional and www.ctdssmap.com. From this Web page, go to technical components of select pathology, medicine “Provider”, then to “Provider Fee Schedule and surgical services to 57.5% of the 2007 Medicare Download”, click on the “I accept” button and then Physician Fee Schedule. The Department is proceed to the “Physician Office and Outpatient Fee implementing this change in order to establish a pricing Schedule” or “Physician Surgical Fee Schedule”. To methodology consistent with Medicare, where, for a access the CSV file, press the control key while given service that includes a professional and technical clicking the CSV link, then select “Open”. component, the fee for the professional component, added together with the fee for the technical For questions about billing or if further assistance is component, equals the global fee. needed to access the fee schedule on the Connecticut Medical Assistance Program Web site, please contact The services impacted include select pathology the HP Provider Assistance Center, Monday through services billed under the LAB rate type off of the Friday from 8:00 a.m. -

Collaborative Practice Agreements and Pharmacists' Patient Care

Collaborative Practice Agreements and Pharmacists’ Patient Care Services A RESOURCE FOR DOCTORS, NURSES, PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS, AND OTHER PROVIDERS COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE AGREEMENTS AND PHARMACISTS’ PATIENT CARE SERVICES | A RESOURCE FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS harmacists can improve patients’ health and the health care delivery system if they are part of the patient’s health care team. One way to achieve this Pharmacist Collaborative goal is with a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) Practice Agreement (CPA) Pbetween pharmacists and other health care providers.1 A formal agreement in which a licensed provider makes Patient care services provided by pharmacists can reduce a diagnosis, supervises patient care, and refers the fragmentation of care, lower health care costs, and improve patient to a pharmacist under a protocol that allows the health outcomes.1 A 2010 study found that patient health pharmacist to perform specific patient care functions. improves significantly when pharmacists work with doctors and other providers to manage patient care.2 The Community Preventive Services Task Force also found strong evidence that matter experts to identify evidence for effective policies, team-based care can improve blood pressure control when a practices, and key supports and barriers to expanding the role pharmacist is included on the team.3 of pharmacists in delivering patient care services and entering into CPAs.4 States regulate pharmacists’ patient care services through “scope of practice” laws and related rules, including boards Consistent with the findings of the Office of the Chief of pharmacy and medicine regulations. Depending on each Pharmacist 2011 Report to the U.S. Surgeon General,1 the state’s laws, pharmacists can work with other health care group found that broad access to patient care services deliv- providers through CPAs to perform an array of patient care ered by pharmacists is limited by policy and compensation services (Figure 1). -

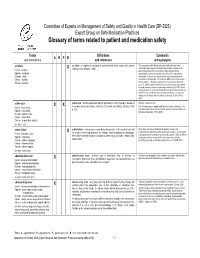

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended.