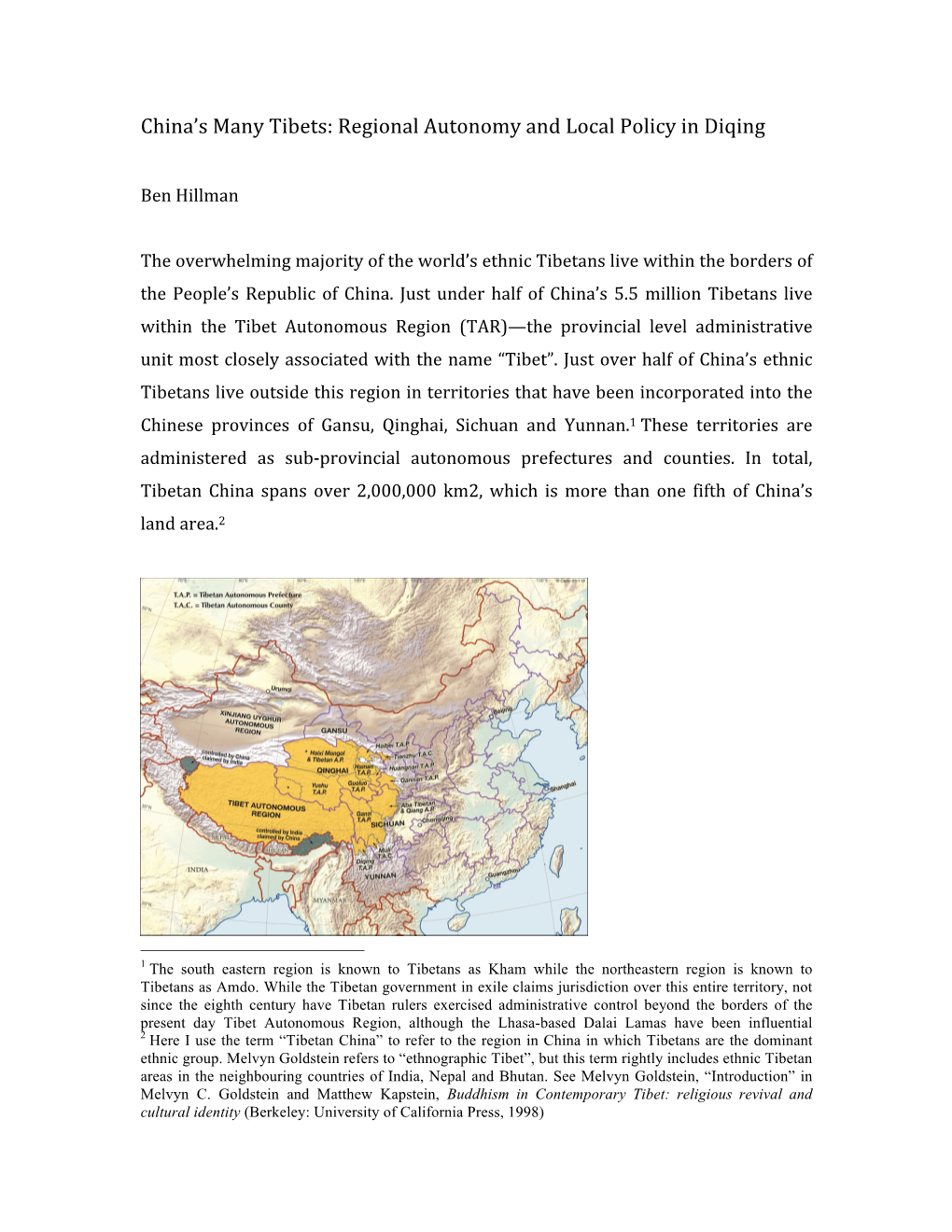

China's Many Tibets: Regional Autonomy and Local Policy in Diqing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Next-Generation Sequencing Improves Thalassemia Carrier Screening Among Premarital Adults in a High Prevalence Population: the Dai Nationality, China

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE © American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Next-generation sequencing improves thalassemia carrier screening among premarital adults in a high prevalence population: the Dai nationality, China Jing He, MS1,2, Wenhui Song, PhD3, Jinlong Yang, BS3,5, Sen Lu, PhD4, Yuan Yuan, MS4, Junfu Guo, MS4, Jie Zhang, PhD2, Kai Ye, BS4, Fan Yang, BS4, Fangfang Long, MS3, Zhiyu Peng, PhD4, Haijing Yu, PhD5, Le Cheng, PhD3,6 and Baosheng Zhu, MS1,2 Purpose: Thalassemia is one of the most common monogenic dis- ite α- and β-thalassemia carriers were missed by traditional screens. eases in southwestern China, especially among the Dai ethnic group. The proportion of such α- and β-thalassemia carriers among the Dai Here, we explore the feasibility of a next-generation sequencing people is 8.6% (82/951). For β-thalassemia carriers, the high ratio (NGS) screening method specifically for the Dai people. (66/99) of CD26 mutations may suggest a correlation between CD26 Methods: Blood samples were obtained from Dai people for premar- and the environmental adaption of the Dai people. ital screening. Double-blind, parallel hemoglobinopathy screening Conclusions: Methodological comparisons demonstrate the superi- was conducted using both traditional hematological methods (red ority of NGS for both sensitivity and specificity, provide a compre- cell indexes and hemoglobin electrophoresis, then DNA sequencing) hensive assessment of thalassemia screening strategies, and indicate and an NGS approach. that NGS is a competitive screening method, especially among popu- Results: Among 951 tested individuals, we found a thalassemia car- lations with a high prevalence of disease. rier rate of 49.5% (471/951) using the NGS screen, in contrast to Genet Med advance online publication 26 January 2017 22.0% (209/951) found using traditional methods. -

Trials of a Tibetan Monk: the Case of Tenzin Delek

Human Rights Watch February 2004, Vol. 16, No. 1 (C) Trials of a Tibetan Monk: The Case of Tenzin Delek Map 1: Provinces and Autonomous Regions of the People’s Republic of China..............................1 Map2: Sichuan Province and Surrounding Areas....................................................................................2 Map 3: Southeastern Section of Kardze/Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture............................3 I. Summary ....................................................................................................................................................5 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................7 A Note on Methodology.........................................................................................................................8 II. Introduction...........................................................................................................................................10 Tenzin Delek ..........................................................................................................................................12 Lobsang Dondrup..................................................................................................................................14 Bombs......................................................................................................................................................15 III. Arrests...................................................................................................................................................17 -

Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau

IPP740 REV World Bank-financed Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Ethnic Minority Development Plan of the Yunnan Highway Assets Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau July 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized EMDP of the Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Summary of the EMDP A. Introduction 1. According to the Feasibility Study Report and RF, the Project involves neither land acquisition nor house demolition, and involves temporary land occupation only. This report aims to strengthen the development of ethnic minorities in the project area, and includes mitigation and benefit enhancing measures, and funding sources. The project area involves a number of ethnic minorities, including Yi, Hani and Lisu. B. Socioeconomic profile of ethnic minorities 2. Poverty and income: The Project involves 16 cities/prefectures in Yunnan Province. In 2013, there were 6.61 million poor population in Yunnan Province, which accounting for 17.54% of total population. In 2013, the per capita net income of rural residents in Yunnan Province was 6,141 yuan. 3. Gender Heads of households are usually men, reflecting the superior status of men. Both men and women do farm work, where men usually do more physically demanding farm work, such as fertilization, cultivation, pesticide application, watering, harvesting and transport, while women usually do housework or less physically demanding farm work, such as washing clothes, cooking, taking care of old people and children, feeding livestock, and field management. In Lijiang and Dali, Bai and Naxi women also do physically demanding labor, which is related to ethnic customs. Means of production are usually purchased by men, while daily necessities usually by women. -

Xinjiang Regional Road Improvement Project (Korla-Kuqa Section)-Qiemo

Ethnic Minority Development Plan Ethnic Minority Development Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 39655 September 2007 PRC: Xinjiang Regional Road Improvement Project (Korla-Kuqa Section) Prepared by Communication Construction Administration Bureau of Xinjiang Uigur Autonomous Region for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The ethnic minority development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Xinjiang Regional Road Improvement Project Qiemo County Local Roads Ethnic Minority Development Plan Communication Construction Administration Bureau of Xinjiang Uigur Autonomous Region March 2007 Ethnic Minority Development Plan Endorsement Letter of Ethnic Minority Development Plan Ministry of Communication and Ministry of Finance have approved Qiemo County Local Road Project which is financed by ADB. The project is planned to commence in 2007 and finish in 2010. According to the requirements of ADB, an EMDP for the project should be compiled in accordance with the Social Safeguards Guidelines of the ADB. Communication Construction Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, with the assistance of PPTA consultants finished this plan. This EMDP is a key planning document of the project, which is approved and monitored by the ADB. Communication Department of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region authorizes Communication Construction Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region to be responsible for the implementation of the project and compilation of the EMDP. Communication Construction Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region has asked for the views on the draft of this EMDP from relevant bureaus, departments, governments of towns or townships, and communities and incorporated those views into the EMDP. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 231 5th International Conference on Community Development (AMCA 2018) Indonesia’s Development Policy to Increase Prosperity of the People in the Border Area Sonny Sudiar Bambang Irawan Mulawarman University, Samarinda Mulawarman University, Samarinda [email protected] [email protected] Abstract. The main issue of this paper highlights the Border area is defined as an area that geographically development policy and prosperity of the people in and demographically adjoins with the borders of a the border area. The border area has always been the country. Scholars exploring the study of international sexiest issues to discuss, as it is identical as a lagging border have developed extensive literatures on the topics and isolated area. The collaboration between the which range from the issue of state’s sovereignty on the government and local communities to overcome those border area [4], the relations between border and problems is needed. In this case, development policy international cooperation [5], the construction of border becomes the key role in order to increase the quality both in physical infrastructure and in intangible of social life especially for the local people. The notion perception of people’s mind [6]-[7] of development has lost its significance due to the One of Indonesia’s most worrying borders is absence of ethics or moral dimension. Practically, the Indonesia-Malaysia border in North Kalimantan. The ethics make the development more meaningful for the problems ranged from high political issues such as entire human life and environment comprehensively. dispute borderlands, damage or missing demarcation Development is a necessity that must be done by every pillars to social and economic issues such as single government to make progress and change for undeveloped region, low or non-existing of basic the better life of the citizens. -

Studies on Ethnic Groups in China

Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page i studies on ethnic groups in china Stevan Harrell, Editor Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page ii studies on ethnic groups in china Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers Edited by Stevan Harrell Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad Edited by Nicole Constable Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China Jonathan N. Lipman Lessons in Being Chinese: Minority Education and Ethnic Identity in Southwest China Mette Halskov Hansen Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928 Edward J. M. Rhoads Ways of Being Ethnic in Southwest China Stevan Harrell Governing China’s Multiethnic Frontiers Edited by Morris Rossabi On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier Åshild Kolås and Monika P. Thowsen Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page iii ON THE MARGINS OF TIBET Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier Åshild Kolås and Monika P. Thowsen UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS Seattle and London Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/7/05 12:47 PM Page iv this publication was supported in part by the donald r. ellegood international publications endowment. Copyright © 2005 by the University of Washington Press Printed in United States of America Designed by Pamela Canell 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. -

Speech by Vice-Governor of the People's Government of Yunnan

Ladies and gentlemen, I am from Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China. I am Vice-Governor of the People’s Government of Yunnan Province. At the same time, I am also an organizer, participant, promoter and witness to HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Yunnan Province, having worked on HIV/AIDS control for 11 years. I would like to extend my great gratitude to UNAIDS and H.E. Mr. Sidibé for inviting me and my colleagues to be here and to have the opportunity to participate in this Board meeting and to share our experiences on HIV/AIDS prevention and control. As we all know, HIV/AIDS is still one of the most important public health issues in the world. It is also the common challenge and responsibility of all governments. In Yunnan Province of the People’s Republic of China, HIV/AIDS prevention and control is an important task. Yunnan Province is located in the southwestern tip of China and has a population of 47 million. There are 25 ethnic minority groups in Yunnan Province, which comprise 33% of the total population. Yunnan Province covers a land area of 394,000 square kilometers and is bordered with Myanmar, Laos and Viet Nam. It shares a 4060-kilometre border with these three countries and is in the vicinity of the Golden Triangle. Yunnan Province is one of the areas worst affected by drug trafficking. It is also one of the most important areas for HIV/AIDS prevention and control in China. By October 2016, 93,437 people had been diagnosed and reported to be living with HIV, which is 14% of the total cases in China. -

Villagers Prove Harsh Environment No Impediment to Transforming Lives

CHINA DAILY | GLOBAL EDITION Tuesday, August 4, 2020 | 3 CHINA Villagers prove harsh environment no impediment to transforming lives Farmers turn mountain slopes into paddy terraces in a fragile zone in Guizhou province No Editor’s note: With China set to meet its goal this year of one eliminating extreme poverty before next year’s 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China, this series left looks at the efforts of different areas of the country to erase behind poverty and improve livelihoods. By CAI HONG in Beijing and YANG JUN in Guiyang n the year 2000, Li Tianliang, a farmer in Lengdong, a village in Qianxinan Buyei and Miao autonomous prefec ture in Southwest China’s Guizhou Iprovince, hired eight strong men to carry his 180kg pig to a market at the foot of the mountain. He was hoping the pig would fetch him at least 1,200 yuan ($171). As the pig was bruised during the tough ride, it didn’t get him the expected price. Li managed to get only 400 yuan. areas, helping villagers to improve their The inaccessibility of the village, which is sources of income. located deep in the mountains, made life dif It was found that honeysuckle grew well ficult for the villagers. in these areas. Since the shrub has wellde The village, with an area of about 730 hec veloped roots, it also helps conserve water, tares, is home to several ethic groups such as say experts. Han, Miao, Buyei and Yi. According to some experiments conducted The villagers made a living through farm in Dewo, a town in the prefecture, one honey A photo taken on Monday shows a view of Lengdong, a village in Qianxinan Buyei and Miao autonomous prefecture in ing, livestock breeding or taking up jobs out suckle plant can conserve up to 200 liters of Southwest China’s Guizhou province. -

Minority Groups Include Zhuang 16.9 Million

China minorityrights.org/country/china/ June 19, 2015 Main minority and indigenous communities: Minority groups include Zhuang 16.9 million (1.3 per cent), Manchu 10.4 million (0.77 per cent), Hui 10.6 million (0.79 per cent), Miao 9.4 million (0.71 per cent), Uyghur 10 million (0.75 per cent), Yi (Lolo) 8.7 million (0.65 per cent), Tujia 8.4 million (0.63 per cent), Mongol 6 million (0.45 per cent), Tibetan 6.3 million (0.45 per cent), etc. (Source: National Population Survey of China, 2010). Main languages: Mandarin Chinese (putonghua), Yue (Cantonese), Wu (Shanghaiese), Minbei (Fuzhou), Minnan (Hokkien-Taiwanese), Qiang, Gan, Hakka, Uyghur, Tibetan, etc. Main religions: Buddhism, Roman Catholicism, Islam, Lamaism (Tibetan Buddhism), Protestantism, Shamanism, Animism, Taoism, Dongba. According to the 2010 Census, China has a population of nearly 1.34 billion people, a figure that includes the 23 million population of Taiwan, which China claims as a breakaway province despite Taiwan’s fully independent political and economic system. The definition of ethnic minorities/nationalities in the People’s Republic of China has been conceived by the state and does not truly reflect the self-identification of such ethnic minorities or the reality of ethnic diversity within China’s boundaries. Mínzú (the Chinese term that signifies non-Han ‘undistinguished ethnic groups’, numbering more than 730,000 people) have not been recognized among or classified within the state’s official 56 ethnic minorities (these comprise the majority Han grouping and 55 minority nationalities). The Minzú also do not include ethnicities that have been classified by the state authorities as belonging to existing minorities and hence denied their legal rights to public participation. -

Guidelines for the Administrative Enforcement of Patents (Draft for Comment)

Intellectual Property: A Key to Sustainable Competitiveness Guidelines for the Administrative Enforcement of Patents (Draft for Comment) State Intellectual Property Office of the People's Republic of China Intellectual Property: A Key to Sustainable Competitiveness Table of Contents Chapter 1 General provisions ............................................................................................................ 1 Part 1 Basic principles of administrative enforcement of patents ............................................ 1 1.1.1 Principle of administration according to law ......................................................... 1 1.1.2 Principle of active case handling ........................................................................... 1 1.1.3 Principle of openness and fairness ......................................................................... 1 1.1.4 Principle of convenience and efficiency ................................................................ 1 1.1.5 Principle of feasibility and innovation ................................................................... 1 Part 2 Jurisdiction .................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Jurisdiction by hierarchy ........................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Jurisdiction by region ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Transfer and designation of jurisdiction ................................................................ -

China COI Compilation-March 2014

China COI Compilation March 2014 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation China COI Compilation March 2014 This COI compilation does not cover the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, nor does it cover Taiwan. The decision to exclude Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan was made on the basis of practical considerations; no inferences should be drawn from this decision regarding the status of Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. -

A Guide to the Use of Chinese Gazetteers* for Amdo Gray Tuttle

A Guide to the Use of Chinese Gazetteers* for Amdo Gray Tuttle 1. Research Tools I. Maps II. Reference Works for the Use and Locating of Gazetteers 2. Sources I. China-General II. Western Regions-General III. Amdo (provincial and sub-provincial gazetteers listed separately) A. Qinghai (Republic, PRC) B. Gansu (Ming, Qing, Republic, PRC) C. Sichuan (Qing, Republic, PRC) IV. Khams (Qing, Republic) V. Central Tibet (Qing, Republic) VI. Western Language Regional Accounts (Qing, Republic, PRC) 3. Secondary Studies I. Chinese language A. Journals B. Articles and Books II. Western language Note on bibliographic format. Title (bold indicates essential for reference) is given first with orginal date of publication in brackets in the case of most reprints (If I have not translated the title, see below for general contents). This is followed by author (last name first), year of publication, series in which the work is found, if applicable. The first asterisk (*) marks my notes on particular sources, mostly including page numbers, with important sections in bold for emphasis. When there are limited or no notes, I probably did not view the work but located the reference. The second asterisk (*) indicates where a particular work is held at Harvard if applicable. Entries with no such information are generally drawn from either Tibet outside the TAR or from my own library and that of Sue Costello (owner of a fairly complete collection of modern gazetteers and maps for Qinghai Amdo).** Note on the translation of Chinese administrative divisions: Sheng is always translated as province. Fu is translated as prefecture for the Ming and Qing periods.