WHY ME? 1. You May Be Wondering (And I Am Too) Why Some Old Duffer of Seventy-Something-Appalling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film, Television and Video Productions Featuring Brass Bands

Film, Television and Video productions featuring brass bands Gavin Holman, October 2019 Over the years the brass bands in the UK, and elsewhere, have appeared numerous times on screen, whether in feature films or on television programmes. In most cases they are small appearances fulfilling the role of a “local” band in the background or supporting a musical event in the plot of the drama. At other times band have a more central role in the production, featuring in a documentary or being a major part of the activity (e.g. Brassed Off, or the few situation comedies with bands as their main topic). Bands have been used to provide music in various long-running television programmes, an example is the 40 or more appearances of Chalk Farm Salvation Army Band on the Christmas Blue Peter shows on BBC1. Bands have taken part in game shows, provided the backdrop for and focus of various commercial advertisements, played bands of the past in historical dramas, and more. This listing of 450 entries is a second attempt to document these appearances on the large and small screen – an original list had been part of the original Brass Band Bibliography in the IBEW, but was dropped in the early 2000s. Some overseas bands are included. Where the details of the broadcast can be determined (or remembered) these have been listed, but in some cases all that is known is that a particular band appeared on a certain show at some point in time - a little vague to say the least, but I hope that we can add detail in future as more information comes to light. -

Trinity College War Memorial Mcmxiv–Mcmxviii

TRINITY COLLEGE WAR MEMORIAL MCMXIV–MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. Hebrews 11: 13 Adamson, William at Trinity June 25 1909; BA 1912. Lieutenant, 16th Lancers, ‘C’ Squadron. Wounded; twice mentioned in despatches. Born Nov 23 1884 at Sunderland, Northumberland. Son of Died April 8 1918 of wounds received in action. Buried at William Adamson of Langham Tower, Sunderland. School: St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, France. UWL, FWR, CWGC Sherborne. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1904; BA 1907; MA 1911. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancshire Allen, Melville Richard Howell Agnew Regiment, 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April 24 1916. Commemorated at Basra Memorial, Iraq. UWL, FWR, CWGC Born Aug 8 1891 in Barnes, London. Son of Richard William Allen. School: Harrow. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity Addy, James Carlton Oct 1 1910. Aviator’s Certificate Dec 22 1914. Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal Flying Corps. Killed in flying Born Oct 19 1890 at Felkirk, West Riding, Yorkshire. Son of accident March 21 1917. Buried at Bedford Cemetery, Beds. James Jenkin Addy of ‘Carlton’, Holbeck Hill, Scarborough, UWL, FWR, CWGC Yorks. School: Shrewsbury. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1910; BA 1913. Captain, Temporary Major, East Allom, Charles Cedric Gordon Yorkshire Regiment. Military Cross. -

The Elms RCI Report 2017

REGULATORY COMPLIANCE INSPECTION FOR SCHOOLS WITH RESIDENTIAL PROVISION THE ELMS SCHOOL APRIL 2017 School’s details School The Elms School DfE Number 884/6001 Registered charity number 843499 Address The Elms School Colwall Malvern Worcestershire WR13 6EF Telephone number 01684 540344 Email address [email protected] Headmaster Mr Alastair Thomas Chair of governors Mr Nat Hone Age range 3 to 13 Number of pupils on roll 174 Boys 87 Girls 87 Day pupils 126 Full 48 boarders EYFS 20 Years 1 & 2 12 Years 3 to 6 79 Years 7 & 8 63 Pupils’ ability Nationally standardised test data provided by the school indicate that the ability of the pupils on entry is above average. Pupils’ needs Thirty-eight pupils require support for special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND). None has a statement of special educational needs or an education, health and care (EHC) plan. Twelve pupils have English as an additional language (EAL) language, nine of whom require additional support for their English. History of the school The philanthropist Humphrey Walwyn founded The Elms School as a co-educational boarding school in 1614, in association with the City of London livery company The Worshipful Company of Grocers. © Independent Schools Inspectorate 2017 April 2017 © Independent Schools Inspectorate 2017 April 2017 Ownership and governing structure The school is a charitable trust, administered by a board of governors. School structure The school includes a Montessori early years setting for children aged 3 to 6 years. The school has one class of pupils in each of Years 2 and 3, and two or three classes per year group from Years 4 to 8. -

REGISTER of STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 27-January-2021

REGISTER OF STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 27-January-2021 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under the Student route of the points-based system. It shows the sponsor's name, their primary location, their sponsor type, the location of any additional centres being operated (including centres which have been recognised by the Home Office as being embedded colleges), the rating of their licence against each route (Student and/or Child Student) they are licensed for, and whether the sponsor is subject to an action plan to help ensure immigration compliance. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about the Student route of the points-based system, please refer to the guidance for sponsors in the Student route on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under the Student route: 1,130 Sponsor Name Town/City Sponsor Type Additional Status Route Immigration Locations Compliance Abberley Hall Worcester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbey College Manchester Manchester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abercorn School London Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Aberdour School Educational Trust Tadworth Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abertay University -

Silver Birch, 8 St. Margarets Road, Hereford, Herefordshire, HR1 1TS Offers in the Region of £425,000 Silver Birch, 8 St

Silver Birch, 8 St. Margarets Road, Hereford, Herefordshire, HR1 1TS Offers in the region of £425,000 Silver Birch, 8 St. Margarets Road, Hereford, Herefordshire, HR1 1TS Properties in this address do not come along very often so count up your silver and take this opportunity while you can! Silver Birch is a detached house, offering 3 bedrooms, parking, a garage, a large, south-facing rear garden and no upward chain. Key Features beautiful countryside views to the The City - Detached House rear. The county city of Hereford is a - 3 Bedrooms & 2 Reception Rooms vibrant and lively city with a very - Well Maintained Accommodation Inside this wonderful home, the cosmopolitan yet traditional - Now in Need of Modernisation ground floor accommodation is made atmosphere, Hereford has been the - Ample Off Road Paring & Attached up of an entrance hall with stairs market and commercial centre of the Garage rising up to the first floor, an open- Herefordshire farming communities - Large, South-Facing Rear Garden plan dining living room, a sizeable for hundreds of years. The city’s 350+ - Distant Countryside Views to Rear rear garden/reception room, a listed buildings are complimented by - Available with No Upward Chain kitchen and a useful utility room with a host of trendy and sophisticated - Desirable Location W.C off. On the first floor, a landing bars and restaurants, the medieval - Approx. 1 Mile from City Centre area gives way to the bathroom, an streets do however still retain many classic public houses and dining The Property airing cupboard and the 3 bedrooms, Introducing Silver Birch, which is a which includes 2 doubles and a single. -

Introduction to Bishopstrow College

Introduction to Bishopstrow College 2020/21 College Overview ◼ Established in 2006, Bishopstrow College is a year-round fully residential International Boarding School for students aged 7-17 years ◼ The College provides English language and academic pathway programmes to prepare international students for entry into boarding schools ◼ Up to 90 international students enrol each term, usually from around 30 different nationalities ◼ Situated on an 8 acre site on the edge of the historic market town of Warminster, close to the attractive cities of Salisbury and Bath 2 © OC&C Strategy Consultants 2013 Accreditation ◼ The College is an accredited member of the Independent Schools Association and the Boarding Schools’ Association ◼ Bishopstrow College is accredited by the British Council for the teaching of English in the UK (highest ranked International Boarding School under the Accreditation UK Scheme) and is a member of English UK ◼ The College is an Authorised Centre for the University of Cambridge English Language Assessment examinations and for the University of Cambridge International Examinations ◼ Bishopstrow is a member of BAISIS, the British Association of Independent Schools with International Students ◼ The College is also an authorised neutral test centre for UKiset 3 © OC&C Strategy Consultants 2013 Key Dimensions of Differentiation ◼ Flexible Model: The College operates as a traditional British boarding school, but with an innovative four term academic year. Students are prepared as quickly as possible for entry into mainstream -

30 April 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 24 APRIL 2021 Chamber Music, Yet He’S Best Known for Rumpole of the Bailey, Brendan

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 24 – 30 April 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 24 APRIL 2021 chamber music, yet he’s best known for Rumpole of the Bailey, Brendan ...... Andrew Wincott and Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo. Mrs Singh ...... Nina Wadia SAT 00:00 Terry Pratchett (b008pc0b) Joseph journeys through his remarkable life and career in Cilla ...... Gbemisola Ikumelo Guards! Guards! conversation with composer, Debbie Wiseman. Colin ...... Sean Baker Episode 5 Captain Noah has been translated into six languages, and is one Gary ...... Sean Baker "That dragon isn't going to accept any mealy-mouthed, wishy- of Horovitz’s best sellers. The Berkshire Maestros, and Burglar ...... Sean Baker washy liberal nonsense.... Do you know what you're getting with conductor David Hill with the Bach Choir, have all rehearsed Producer: Alexandra Smith a dragon? Unashamed strong leadership." and performed this work, and give their views on its lasting A BBC Studios production for BBC Radio 4 first broadcast in The dragon strikes. But will Captain Vimes triumph? popularity. Dancer Wayne Sleep, conductor John Wilson, and December 2016. Stars John Wood and Martin Jarvis. TV executive producer Tony Wharmby, also discuss their SAT 05:30 The Confessional (m000v848) The 8th of Terry's Pratchett's comic fantasy stories set on musical collaborations with Horovitz. Series 1 Discworld. Horovitz's story begins with his escape from the Nazis as they The Confession of Cariad Lloyd Narrator …. Martin Jarvis entered Vienna in 1938, to then include giving wartime musical Actor, comedian and broadcaster Stephen Mangan presents a Captain Vimes …. John Wood appreciation lectures to the forces, being awarded two Ivor new comedy chat show about shame and guilt. -

TRINITY COLLEGE MCMXIV-MCMXVIII Iuxta Fidem

TRINITY COLLEGE MCMXIV-MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. (The Vulgate has ‘supra terram’, and includes the ‘eas’ which is missing from the inscription.) These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. (Hebrews 11: 13) Any further details of those commemorated would be gratefully received: please contact [email protected]. Details of those who appear not to have lost their lives in the First World War, e.g. Philip Gold, are given in italics. Adamson, William Allen, Melville Richard Howell Armstrong, Michael Richard Leader Born Nov. 23, 1884 at Sunderland, Agnew Born Nov. 27, 1889, at Armagh, Ireland. Northumberland. Son of William Adamson, Son of Henry Bruce Armstrong, of Deans Born Aug. 8, 1891, in Barnes, London. Son of Langham Tower, Sunderland., Sherborne Hill, Armagh. School, Cheltenham College. of Richard William Allen. Harrow School. School. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity, Admitted as pensioner at Trinity, June 25, Admitted as pensioner at Trinity, Oct. 1, June 25, 1904. BA 1907, MA 1911. 1908 (Mechanical Science Tripos). BA 1910. Aviator’s Certificate, Dec. 22, 1914. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancs. Regiment, 1911. 2nd Lieutenant, Royal Field Artillery Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April and Royal Engineers (150th Field Flying Corps. Killed in flying accident, 24, 1916. Commemorated at Basra Company). -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 30 November – 6 December 2013 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 30 NOVEMBER 2013 Ena/Bunty/Betty

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 30 November – 6 December 2013 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 30 NOVEMBER 2013 Ena/Bunty/Betty ...... Gabriel Quigley relationships that grew out of them. Doogie ...... Matt Costello The programme also hears from poet Alan Brownjohn about SAT 00:00 Simon Bovey - Slipstream (b009mbjn) The Minister ...... Robert Paterson the experience of sitting for Fay, and examines an archive of Fight for the Future Producers: Lucy Bacon and Kathy Smith prints, contact sheets and letters from her sitters, held in the Jurgen and Kate are desperate to get the weapon away before all First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in April 2000. British Library since her death in 2005, with photo critic and is lost... SAT 02:30 The Change (b00nxcbs) editor Sue Steward. Conclusion of Simon Bovey's sci-fi adventure series set during Series 1 SAT 08:00 Garrison Keillor's Radio Show (b019jqtz) the Second World War. Lipstick Series 7 Stars Rory Kinnear as Jurgen Rall, Tim McMullan as Major Carol's attempts at keeping George's little hobby a secret are Episode 14 Barton, Joannah Tincey as Kate Richey, Ben Crowe as thwarted when they bump into Maureen... From Minnesota, the American funny man presents the Lieutenant Dundas, Rachel Atkins as Trudi Schenk, Peter Lynda Bellingham and Chris Ellison star as troubled hormonal VocalEssence ensemble, plus news from deeply frozen Lake Marinker as Brigadier Erskine and Laura Molyneux as wife Carol whose husband George has revealed that he's a Wobegon. From 2011. Slipstream. transvestite. SAT 09:00 A Taste of Funny with Denis Norden (b007s6p7) Other parts played by Simon Treves, Sam Pamphilon, Alex Sitcom by Gavin Petrie and Jan Etherington. -

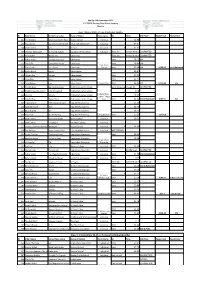

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012 Organisation Name Total More House School Ltd 5 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE 65 360 GSP College 15 4N ACADEMY LIMITED † 5 E Ltd 10 A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON 20 A+ English Ltd 5 A2Z School of English 40 Abacus College 30 Abberley Hall † Abbey College 120 Abbey College Cambridge 140 Abbey College Manchester 55 Abbots Bromley School for Girls 15 Abbotsholme School 25 ABC School of English Ltd 5 Abercorn School 5 Aberdeen College † Aberdeen Skills & Enterprise Training 30 Aberystwyth University 520 ABI College 10 Abingdon School 20 ABT International College † Academy De London 190 Academy of Management Studies 35 ACCENT International Consortium for Academic Programs Abroad, Ltd. 45 Access College London 260 Access Skills Ltd † Access to Music 5 Ackworth School 50 ACS International Schools Limited 50 Active Learning, LONDON 5 Organisation Name Total ADAM SMITH COLLEGE 5 Adcote School Educational Trust Limited 20 Advanced Studies in England Ltd 35 AHA International 5 Albemarle Independent College 20 Albert College 10 Albion College 15 Alchemea Limited 10 Aldgate College London 35 Aldro School Educational Trust Limited 5 ALEXANDER COLLEGE 185 Alexanders International School 45 Alfred the Great College ltd 10 All Hallows Preparatory School † All Nations Christian College 10 Alleyn's School † Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education † ALPHA COLLEGE 285 Alpha Meridian College 170 Alpha Omega College 5 Alyssa School 50 American Institute for Foreign Study 100 American InterContinental University London Ltd 85 American University of the Caribbean 55 Amity University (in) London (a trading name of Global Education Ltd). -

Memories of Life in Wigan During the 1960'S and 1950'S

A BETA Project Wigan Market Place 1960’s Memories of Life in Wigan during the 1960’s and 1950’s BETA is a Registered Charity No. 1070662 1 Black 5 at Wigan North West Station Standishgate Wigan opposite St. John’s RC Church Market Square Wigan showing the underground public toilets Wigan Corporation bus at Bus station Wigan Pier Wigan Market Square 2 BETA PROJECT DO YOU REMEMBER? ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to give a special thank you to all those who contributed memories for our book. Molly Blay Vera and Joe Hilton Eileen and Eddie Knight Doreen Almond Eileen and Mike Bithell Eileen and George Walsh and all those who told us their stories Ron Hunt and Wigan World web site for photographs Lancashire On Line Parish Clerk Project Mike Fletcher’s book ‘The Making of Wigan’ Wigan Observer All those who contributed Funded by Deal for the Communities Do you remember the 1960’s and 1950’s? Thanks to a grant from Deal for the Communities, BETA’s Eileen Bithell and Eileen Walsh brought together a group of older people who have researched and written about local life in these decades. We hope you enjoy reading about Life in the 1960’s and 1950’s and that this will bring back some memories of your past. 3 The Wedding of Princess Margaret, the Queen’s sister 4 1960 Prince Andrew is born on 19th February to The Queen and Prince Philip Princess Margaret, the Queen’s sister, married Anthony Armstrong-Jones on 6th May. The Prime Minister was Harold MacMillan First Traffic Wardens are deployed National Service Conscription ends In May 1960, Wigan RLFC beat Wakefield Trinity 27 -3 to become League Champions At the summer Olympics in Rome, Cassius Clay – later restyled himself Mohammad Ali – won gold in boxing. -

Sunday Score Sheets

Sunday 15th September 2019 CLC NSEA Rectory Farm Show Jumping Results Class 1 Novice 80-85cm Team & Individual Qualifier ID Rider Name Horse/Pony name Name of School Team Name SJ Time Ind Place Team Total Team Place 201 Tilly Bamford Ballyknock Master Roan Dragon School Individual 4 33.98 204 Mya Harvey Dancing Queen II (Coco) Royal High School Bath Individual 4 37.91 205 Oliver Cherry Lola Burford Individual 8 37.21 206 Clemmie Macdonald Riverwood Surprise Hazelgrove Prep School Individual Rider fall walked from arenaELIMINATED 221 Freya Soden Narabo Lily Cokethorpe Rider fall walked from arenaELIMINATED 207 Arthur Butler Lassban Grey Duke Cokethorpe clear 28.19 8th 223 Ella Goffe SpringWind Pro Set Cokethorpe clear 28.06 7th Cokethorpe 224 Grace Soden Joe’s Oscar Cokethorpe School clear 27.38 6th 0/83.63 1st Q Nationals 213 Archie Stamp Harper Sidcot School 4 29.64 214 Harriet Blair Morgan Sidcot School clear 39.85 215 Hugo Blair Occy Sidcot School clear 36.21 216 Daisy Bowles Lucy Sidcot School Sidcot Stars clear 26.56 5th 0/102.62 5th 217 Carlotta Boas Buckland Drummer Cheltenham Ladies College error of course missed 12 ELIMINATED 218 Martha Llewellen Palmer Colonel Mustard Cheltenham Ladies College 4 34.8 219 Lily Hine Murphy Cheltenham Ladies College Cheltenham 4 28.43 Ladies College 220 Isabella Boas Mylers Minx Cheltenham Ladies College Kites clear 24.32 1st Q Nationals 8/87.55 6th 209 Tegan O'Neill Ketford Angel Delight King Alfred's Academy 4 34.17 210 Kayleigh O'Neill Blue King Alfred's Academy 8 32.43 211 Kitty Winfield Leo