Reflecting on Zion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cape Town

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University CHANGING MIGRANT SPACES AND LIVELIHOODS: HOSTELS AS COMMUNITY RESIDENTIAL UNITS, KWAMASHU, KWAZULU NATAL SOUTH AFRICA By Nomkhosi Xulu Thesis Presented for the Degree of Town DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHYCape of in the Department of Sociology UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN University February, 2012 Table of Contents Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................... 4 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER ONE ...................................................................................................................... 6 Unveiling the Hostel’s Perplexity ........................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Hostels as Spaces of Perplexity ....................................................................................... 8 1.2 Key Concepts ................................................................................................................ -

The Case of the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Revisiting ‘Translatability’ and African Christianity: The Case of the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion The example of Christian Zionism in South Africa seems to perfectly illustrate the scholarly vogue for portraying Christianity in Africa as an eminently ‘translatable’ religion. Zionism – not to be confused with the Jewish movement focused on the state of Israel – is the largest popular Christian movement in modern Southern Africa, to which millions in South Africa, Swaziland, Lesotho, Mozambique, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zimbabwe belong; by the 1960s, 21% of Southern Africans were Zionist.1 However, with now over three thousand active Zionist churches in the Southern African region, there is no single Zionist organization. The biggest is the Zion Christian Church in northern South Africa, with six million members, while the vast majority of Zionist churches have between fifty and two hundred members.2 Adherents of this diffuse, decentralized movement have historically been drawn from South Africa’s working-classes; today, Zionists are still perceived as representative of the rank of minimally educated, economically marginalized black South Africans. And although thus vastly diverse, a unifying feature of Zionists across this region is their emphasis on health and healing. Almost uniformly, a Zionist service centers on a healing event during which congregation members receive prayer from a ‘prophet’ for a physical, emotional or psychological ailment. Some churches still eschew both Western and African medicine in favor of exclusive reliance upon prayer.3 Both scholarship and popular perception have largely understood Zionism as a uniquely Southern African phenomenon, entirely indigenous to the region. -

11 a MORULA TREE BETWEEN TWO FIELDS. 11 the Commentary of Selected Tsonga Writers on Missionary Christianity

11 A MORULA TREE BETWEEN TWO FIELDS. 11 The Commentary of Selected Tsonga Writers On Missionary Christianity By SAMUEL TINYIKO MALULEKE Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF J.N.J. KRITZINGER June 1995 Student Number: 567-423-9 I declare that "A Morula Tree Between Two Fields." The Commentary of Selected Tsonga Writers On Missionary Christianity is my own work and all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. SIGNATURE (S.T. Maluleke) DATE Centre for Science and Development: Acknowledgement The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed in this thesis and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science and Developemt. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY .......... vii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii CHAPTER 1 . I MISSIONARY INTERVENTION AMONGST THE VATSONGA - AN INTRODUCTION I I.I Statement and Outline ........... I 1.2 Black Theology of Liberation as a Framework . 4 1.3 The beginnings of the SMSA - A brief history 6 1.3 .1 Swiss Background . 6 1.3.2 The Lesotho Connection . 8 1.3.3 Pedi, Venda Chiefdoms and other Missionary Societies I2 1.3 .4 Joao Albasini . 16 1.3. 5 The Basotho Evangelists Initiate work at Spelonken 19 1.4 The ideological and historiographical problematic ..... 20 1.4.1 An Indigenous Commentary ......... 26 I.4.2 The abiding impact of missionary intervention 29 I.4.3 Can an Indigenous Commentary be Constructed? 34 1.5 Sources 38 I.5.1. -

The Politics of Cultural Conservatism in Colonial Botswana: Queen Seingwaeng's Zionist Campaign in the Bakgatla Reserve, 1937-1947

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, vo1.12, nos.1 & 2 (1998) The politics of cultural conservatism in colonial Botswana: Queen Seingwaeng's Zionist campaign in the Bakgatla Reserve, 1937-1947 Fred Morton Loras College, Iowa, & University of Pretoria Abstract Studies of Christian Zionist churches in southern Africa have suggested that they were non-political. This paper puts the growth of Zionism among the BaKgatla in the context of local political struggles and the life of Queen Seingwaeng, mother of Chief Molefi. She was politically important from the 1910s until the 1960s, articulating the views of ordinary people otherwise considered politically helpless. She led popular opposition to the ''progressive'' authoritarianism of Regent 1sang, promoting the restoration of her son Molefi to chieftainship through religious movements in the 1930s-andjoining the Zion Christian Church in 1938. However, by 1947, Seingwaeng and the Zionists were seen as a political threat by Molefi and the ruling elite, who expelled them from BaKgatla territory. Molefi was reconciled with his mother in 1955, but she did not return home to Mochudi until 1967, nine years after his death. In 1947, Queen Mother Seingwaeng was beaten in public by her son Molefi, kgosi (king) of the BaKgatla, for refusing to abandon the Zion Christian Church (ZCC). -

Alternation Article Template

Women’s Leadership and Participation in Recent Christian Formations in Swaziland: Reshaping the Patriarchal Agenda? Sonene Nyawo ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3542-8034 Abstract Swaziland1 is experiencing a proliferation of new religious bodies, as elsewhere in Africa, including emerging expressions of Christianity established by women. In this strongly patriarchal context, women, through recent Christian formations, go against the grain, and become pastors, evangelists, prophets and healers. The questions are, how do women appear to blend in when they take the lead in creating ecumenical associations? How do they constitute their own spaces within patriarchy, whilst accomplishing ecumenically inclusive Christian fellowship among themselves? The answers are provided through a case study of Mhlabuhlangene Prayer Group (MPG). It is argued that Christian women engage, not in resistance, but in negotiation, which keeps a model of their relationships and their spirituality in conformity with the patriarchal agenda. The case demonstrates in detail the occasions and activities through which women create their own spaces of Christian devotion whilst they simultaneously affirm patriarchal values. My data was generated from a particularly significant sample and through participant observation, which provide evidence that MPG is an ecumenical movement that ‘builds on the indigenous’. However, the paper argues that the women’s compliant approach to expressing their spirituality requires certain modifications, which are meant to lead to full inward empowerment. Keywords: feminism, leadership, participation, Christian formations, patri- archy 1 In April 2018, King Mswati III changed the name of the country from Swaziland to Kingdom of Eswatini. The initial rendition is retained in this article. -

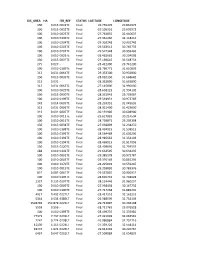

27.126882 32.804893 17240475 1724.047 0231ST Short T

GIS_AREA HA ITB_REF STATUS LATITUDE LONGITUDE 8660 0.866 0228ST Short Term -27.126882 32.804893 17240475 1724.047 0231ST Short Term -26.961461 32.380427 2011 0.201 0217ST Short Term -27.479305 32.585970 1078584 107.858 0223ST Short Term -28.068387 30.714147 3206 0.321 0253ST Short Term -29.810959 30.633534 794 0.079 0254ST Short Term -29.685407 30.191637 27405 2.740 0307ST Short Term -27.357435 32.525365 2441 0.244 0256ST Short Term -27.480721 32.580146 48735 4.873 0260ST Short Term -27.673490 32.442569 66305 6.630 0310ST Short Term -27.986685 31.933612 867 0.087 0271ST Short Term -29.995656 30.890788 2229 0.223 0306ST Short Term -29.658219 30.637166 689 0.069 0263ST Short Term -29.971258 30.905562 1513496 151.350 0169ST Short Term -27.409977 32.056195 1247347 124.735 0370ST Short Term -27.408065 32.199667 8343 0.834 0332ST Short Term -27.508405 32.654804 2156 0.216 0389ST Short Term -27.324274 32.717313 1217 0.122 0364ST Short Term -30.016856 30.806685 921 0.092 0382ST Short Term -30.015064 30.806296 902 0.090 0367ST Short Term -30.054714 30.847411 271391 27.139 0309ST Short Term -28.790151 29.198954 560884 56.088 0335ST Short Term -28.795229 29.206533 91851 9.185 0437ST Short Term -30.155435 30.739699 16196 1.620 0452ST Short Term -28.346153 30.543835 723 0.072 0451ST Short Term -30.784050 30.126504 1274 0.127 0450ST Short Term -29.983960 30.877987 498 0.050 0443ST Short Term -28.879869 31.912751 381 0.038 0442ST Short Term -28.879749 31.912868 468 0.047 0436ST Short Term -28.778714 31.843655 67 0.007 0396ST Short Term -28.338725 31.419357 -

150 Years of Mission-Churches in Swaziland, 1844 -1994 Eutism: a Factor in Tiie Growtii and Decune

150 YEARS OF MISSION-CHURCHES IN SWAZILAND, 1844 -1994 EUTISM: A FACTOR IN TIIE GROWTII AND DECUNE by MARJORIE FROISE submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY • at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR N J SMITH NOVEMBER 1996 SUMMARY In 1994, Swaziland celebrated 150 years of Christianity. Three distinct eras are identified in the history of mission-church growth, each of which is related to elitism. 1884 saw the start of missions is Swaziland, but this effort was short-lived. The mission became caught up in internecine warfare, the resident missionary and the Swazi Christian community fled to Natal where the church grew and matured in exile during a period of missionary lacuna in Swaziland itself. After thirty-six years, the missionaries were once again allowed to settle in Swaziland and the church grew rapidly, mainly as a result of the widespread institutional work undertaken. Soon an elite Christian community developed as people came to identify with a mission or church, many of whom had little Christian commitment. In 1%8, Swaziland was granted independence. A return to culture accompanied a strong wave of nationalism. Mission-church growth in this period declined as those, whose commitment to the Christian faith was shallow, returned to culture or joined one of the Independent churches which catered for varying degrees of syncretism The third era outlined in this study is one of secularisation. Family structures were eroded, materialism took hold and the church was in danger of becoming irrelevant. The older churches continue their decline, but new churches, appealing particularly to the new elite, are growing. -

Gis Area Ha Itb Ref Status Latitude

GIS_AREA HA ITB_REF STATUS LATITUDE LONGITUDE 150 0.015 0031TE Final -29.755376 29.861975 150 0.015 0032TE Final -29.105316 29.699972 100 0.010 0025TE Final -27.764855 32.440637 100 0.010 0196TE Final -27.961260 32.118216 100 0.010 0204TE Final -29.303248 30.901742 100 0.010 0203TE Final -29.563513 30.765735 100 0.010 0201TE Final -29.572348 30.959465 100 0.010 0026TE Final -28.482681 30.204008 150 0.015 0037TE Final -27.169616 32.548754 275 0.027 - Final -28.412300 29.741200 100 0.010 0189TE Final -28.786771 31.610895 313 0.031 0064TE Final -29.353300 30.932800 150 0.015 0035TE Final -28.010150 31.668642 313 0.031 - Final -28.352800 31.655800 313 0.031 0063TE Final -27.145800 31.990000 100 0.010 0029TE Final -28.658123 31.994102 150 0.015 0030TE Final -28.331943 29.703087 100 0.010 0199TE Final -29.518951 30.973769 143 0.014 0005TE Final -28.293351 32.045095 313 0.031 0006TE Final -28.321400 31.423600 313 0.031 0007TE Final -30.191900 30.608900 100 0.010 0011TE Final -29.627881 30.214504 100 0.010 0016TE Final -28.759872 29.209398 150 0.015 0038TE Final -27.038009 32.238250 100 0.010 0188TE Final -28.494915 31.538515 100 0.010 0191TE Final -28.564468 31.636206 100 0.010 0192TE Final -28.985662 31.354103 100 0.010 0194TE Final -28.469913 31.917096 150 0.015 0220TE Final -28.403692 31.704555 188 0.019 0141TE Final -29.632595 30.634235 100 0.010 0001TE Final -29.385178 30.972787 100 0.010 0003TE Final -29.376149 30.865294 100 0.010 1470TE Final -28.225001 30.559247 100 0.010 0015TE Final -29.259892 30.783376 822 0.082 0062TE Final -29.537835 -

A Comparative Study of the Responses of Tiyo Soga and Mpambani Mzimba to the Scottish Missionary Enterprise

"SUBVERSIVE SUBSERVIENCE": A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE RESPONSES OF TIYO SOGA AND MPAMBANI MZIMBA TO THE SCOTTISH MISSIONARY ENTERPRISE. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN BY MALINGE McLAREN NJEZA AUGUST 2000 RONDEBOSCH, CAPE TOWN The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS AlC~OVVLEIMJE~S.................... .................... lii .ABSTRACT. vi INTRODUCflON . 1 CHAPTER 1 . 12 EVANGEUZING 7HE NAlTIVE' - SCOmSH MISSIONS ON THE EAlS~FllONTIEFt... ......................... ... ............. 12 The Scottish Mission and the R.harhabe Factor. .. 19 Van der Kemp, Williams and the A.maR.harhabe-Xhosa. .. 24 The 1820 British Settlement.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 31 Brownlee and Beginnings of the Scottish Mission. 36 Mission Stations as sacred spaces of Disruption . .. .. .. 40 CH.AP1'EFt 2 . 46 'COLONIZING THE MIND' - THE LOVEDALE EXPERIMENT. 46 The Establishment ofLovedale. 55 William Govan: Teacher ofSoga. 60 James Stewart: Teacher ofMzimba . 65 The 'classics debate': Education for Equality or 'Colonizing the Mind'? . 70 CH.APTER. 3 . 86 TIYO SOGA STRADDLING TWO CULTURES. 86 Early Formation and the Lovedale Experience. 86 The Scottish Experience. 93 Aln Alwakening of Afucan Consciousness. 100 The Final Return . 104 11 CHAPTER 4 .................................................... 117 SOOA: LITERARY RESPONSE TO EUROPEAN CHRISTIANITY. -

An Anthropological Study of Healing Practices in African Initiated Churches with Specific Reference to a Zionist Christian Church in Marabastad

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF HEALING PRACTICES IN AFRICAN INITIATED CHURCHES WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO A ZIONIST CHRISTIAN CHURCH IN MARABASTAD by JACQUELINE MARTHA FRANCISCA (JACKEY) WOUTERS submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject ANTHROPOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Supervisor: Professor CJ Van Vuuren September 2014 Student number: 0900-207-3 I declare that AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF HEALING PRACTICES IN AFRICAN INITIATED CHURCHES WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO A ZIONIST CHRISTIAN CHURCH IN MARABASTAD is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. I further declare that I have not previously submitted this work, or part of it, for examination at Unisa for another qualification or at any other higher education institution. …………….. …………….. SIGNATURE DATE i I dedicate this study to my parents and sister, Jack, Martha and Irma Wouters, who have always been there for me. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to respectfully and deeply thank the members of the Zion Christian Church for allowing me into their sacred environment and for opening up a whole new world to me. This exhilarating experience enabled remarkable personal growth. They helped me understand how the Zion Christian Church contributed towards people’s quest for absolute health, which in an African context encompasses physical, social, spiritual and secular levels. Their assistance and that of my interpreters was pivotal in compiling this study that aims to enlighten readers on the workings of the church’s successful healing ministry from an anthropological perspective. -

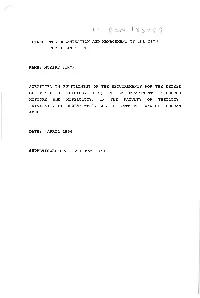

(I) the ORGANISATION and MANAGEMENT of the ZION CHRISTIAN CHURCH. NAME: MORIPE SIMON SUBMITTED in FULFILLMENT of the REQUIREMENT

(i) TITLE: THE ORGANISATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE ZION CHRISTIAN CHURCH. NAME: MORIPE SIMON SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY (DTH) IN THE DEPARTMENT OF CHURCH HISTORY AND MISSIOLOGY, IN THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF DURBAN-WESTVILLE, PRIVATE BAG X54001, DURBAN 4000. DATE: APRIL 1996 SUPERVISOR: PROF. A B MAZIBUKO (ii) DECLARATION I DECLARE THAT THE THESIS HEREBY SUBMITTED BY ME FOR A DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY HAS NOT PREVIOUSLY BEEN SUBMITTED BY ME FOR A DEGREE AT THIS OR ANY OTHER UNIVERSITY, AND THAT THIS IS MY OWN WORK IN DESIGN AND IN EXECUTION, AND THAT ALL MATERIAL CONTAINED THEREIN HAS BEEN DULY ACKNOWLEDGED. (iii) DEDICATION THIS THESIS IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED TO MY LATE FATHER, LEDIMANE AND MY MOTHER NKOLA. (iv) CONTENTS RESEARCH METHODOLOGy ' viii SUMMARY •••••••••••••••.••••.•••.••••.••••••••.. lX -X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi - xii INTRODUCTION • ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••xiii - xv CHAPTER 1 1 1. Background of the Zion Christian Church..... 1 - 8 1.1. The rise of the Zionist Movernent 8 - 16 1.2. The call of Engenas Lekganyane ~ 16 - 22 1.3. The successors of Engenas Lekganyane 22 - 29 1.4. Taboos and holiness in the Zion Christian Church 30 - 47 1.5. The headquarters of the Zion Christian Church. ..........................................48 - 49 CHAPTER 2 ..•........•............................50 2. Organisation 50 - 58 2.1. The holy week conference 59 . (v) 2.1.1. Powers and duties of the conference.... 60 - 65 2.2. September conference 65 - 68 2.3. Christmas conference 68 - 69 2.4. The role of women 69 - 76 2.5. The main characteristics of the Zion Christian Church 76 2.5.1. -

Chapter Twelve Zionists, Aladura and Roho: African Instituted Churches

Chapter Twelve Zionists, Aladura and Roho: African Instituted Churches Afe Ado game & Lizo Jafta INTRODUCTION The indigenous religious creativity crystallizing in the acronym, African Instituted Churches (AICs) represents one of the most profound developments in the transmission and transformation of both African Christianity and Christianity in Africa. Coming on the heels of mission Christianity and the earliest traces of indigenous appropriations in the form of Ethiopian churches and revival movements, AICs started to emerge in the African religious centre-stage from the 1920s and 1930s. The AICs now constitute a significant filament of African Christian demography. In an evidently contemporaneous feat, this religious manifestation came to limelight ostensibly under similar but also remarkably distinct historical, religious, cultural, socio-economic and political circumstances particularly in the western, southern and eastern fringes of the continent. Their unprecedented upsurge particularly in a colonial, pre-independent milieu era evoked wide-ranging reactions and pretensions of a political and socio religious nature, circumstances that undercut their bumpy rides into prominence both in public and private spheres. The AIC phenomenon in Africa has received considerable scholarly attention since the fourth decade of the last century. Available literature reveals the conspicuous dominance of theological, missiological, sociological perspectives and provides ample information regarding this complex but dynamic religious development.