University of Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

27.126882 32.804893 17240475 1724.047 0231ST Short T

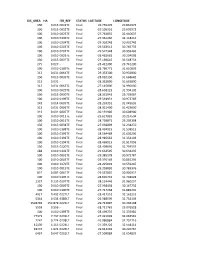

GIS_AREA HA ITB_REF STATUS LATITUDE LONGITUDE 8660 0.866 0228ST Short Term -27.126882 32.804893 17240475 1724.047 0231ST Short Term -26.961461 32.380427 2011 0.201 0217ST Short Term -27.479305 32.585970 1078584 107.858 0223ST Short Term -28.068387 30.714147 3206 0.321 0253ST Short Term -29.810959 30.633534 794 0.079 0254ST Short Term -29.685407 30.191637 27405 2.740 0307ST Short Term -27.357435 32.525365 2441 0.244 0256ST Short Term -27.480721 32.580146 48735 4.873 0260ST Short Term -27.673490 32.442569 66305 6.630 0310ST Short Term -27.986685 31.933612 867 0.087 0271ST Short Term -29.995656 30.890788 2229 0.223 0306ST Short Term -29.658219 30.637166 689 0.069 0263ST Short Term -29.971258 30.905562 1513496 151.350 0169ST Short Term -27.409977 32.056195 1247347 124.735 0370ST Short Term -27.408065 32.199667 8343 0.834 0332ST Short Term -27.508405 32.654804 2156 0.216 0389ST Short Term -27.324274 32.717313 1217 0.122 0364ST Short Term -30.016856 30.806685 921 0.092 0382ST Short Term -30.015064 30.806296 902 0.090 0367ST Short Term -30.054714 30.847411 271391 27.139 0309ST Short Term -28.790151 29.198954 560884 56.088 0335ST Short Term -28.795229 29.206533 91851 9.185 0437ST Short Term -30.155435 30.739699 16196 1.620 0452ST Short Term -28.346153 30.543835 723 0.072 0451ST Short Term -30.784050 30.126504 1274 0.127 0450ST Short Term -29.983960 30.877987 498 0.050 0443ST Short Term -28.879869 31.912751 381 0.038 0442ST Short Term -28.879749 31.912868 468 0.047 0436ST Short Term -28.778714 31.843655 67 0.007 0396ST Short Term -28.338725 31.419357 -

Gis Area Ha Itb Ref Status Latitude

GIS_AREA HA ITB_REF STATUS LATITUDE LONGITUDE 150 0.015 0031TE Final -29.755376 29.861975 150 0.015 0032TE Final -29.105316 29.699972 100 0.010 0025TE Final -27.764855 32.440637 100 0.010 0196TE Final -27.961260 32.118216 100 0.010 0204TE Final -29.303248 30.901742 100 0.010 0203TE Final -29.563513 30.765735 100 0.010 0201TE Final -29.572348 30.959465 100 0.010 0026TE Final -28.482681 30.204008 150 0.015 0037TE Final -27.169616 32.548754 275 0.027 - Final -28.412300 29.741200 100 0.010 0189TE Final -28.786771 31.610895 313 0.031 0064TE Final -29.353300 30.932800 150 0.015 0035TE Final -28.010150 31.668642 313 0.031 - Final -28.352800 31.655800 313 0.031 0063TE Final -27.145800 31.990000 100 0.010 0029TE Final -28.658123 31.994102 150 0.015 0030TE Final -28.331943 29.703087 100 0.010 0199TE Final -29.518951 30.973769 143 0.014 0005TE Final -28.293351 32.045095 313 0.031 0006TE Final -28.321400 31.423600 313 0.031 0007TE Final -30.191900 30.608900 100 0.010 0011TE Final -29.627881 30.214504 100 0.010 0016TE Final -28.759872 29.209398 150 0.015 0038TE Final -27.038009 32.238250 100 0.010 0188TE Final -28.494915 31.538515 100 0.010 0191TE Final -28.564468 31.636206 100 0.010 0192TE Final -28.985662 31.354103 100 0.010 0194TE Final -28.469913 31.917096 150 0.015 0220TE Final -28.403692 31.704555 188 0.019 0141TE Final -29.632595 30.634235 100 0.010 0001TE Final -29.385178 30.972787 100 0.010 0003TE Final -29.376149 30.865294 100 0.010 1470TE Final -28.225001 30.559247 100 0.010 0015TE Final -29.259892 30.783376 822 0.082 0062TE Final -29.537835 -

Reflecting on Zion

CHAPTER 7 REFLECTING ON ZION We don't have theology. We dance - Bill Moyers Africa swallowed the conqueror's music and sang a new song of her own - Barbara Kingsolver Missionaries came to black Africa. They brought with them the treasure of the Gospel contained in the earthen vessel of Western Christianity, Christianity being the accumulative heritage of the response of the natives of Europe to the Christian message. The missionaries were generally satisfied to be instru mental in transferring their Gospel and culture', cast in the mould to which they added the adjective 'Christian'. Under their direction hundreds of thousands of people became members of the mission churches by accepting Christianity. Since the last decades of the nineteenth century widespread dissatisfaction has arisen and the black Christians no longer felt at home in the missionaries' churches. They responded in different ways, evidencing alternative understandings of what it meant to be Christian. Some remained in these churches where, in time, African leadership took over, seeking to foster an African identity while valuing their traditional heritage. A large proportion opted to act independently, maintaining the Western ecclesias tical traditions. Others, while regarding themselves as Christians, enacted their faith in the African theatre by founding indigenous churches, which embodied many traditional African features. Migration was one of the major factors in the spread of these indigenous churches to urban areas. Migrants came to the cities from their homesteads and villages in the rural areas. The characteristic social cohesion of the previous small-scale society where personal relationship» prevailed made way for disrup tion, individualism and impersonality. -

Shembe Religion's Integration of African Traditional Religion

Shembe religion’s integration of African Traditional Religion and Christianity: A sociological case study A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of Rhodes University by Nombulelo Shange Supervisor: Michael Drewett Department of Sociology July 2013 Abstract The Shembe Church‟s integration of African Traditional Religion and Christianity has been met by many challenges. This merger has been rejected by both African traditionalists and Christians. The Shembe Church has been met by intolerance even though the movement in some ways creates multiculturalism between different people and cultures. This thesis documents the Shembe Church‟s ideas and practices; it discusses how the Shembe Church combines two ideologies that appear to be at odds with each other. In looking at Shembe ideas and practices, the thesis discusses African religion-inspired rituals like ukusina, ancestral honouring, animal sacrificing and virgin testing. The thesis also discusses the heavy Christian influence within the Shembe Church; this is done by looking at the Shembe Church‟s use of The Bible and Moses‟ Laws which play a crucial role in the Church. The challenges the Shembe Church faces are another main theme of the thesis. The thesis looks at cases of intolerance and human rights violations experienced by Shembe members. This is done in part by looking at the living conditions at eBuhleni, located at Inanda, KZN. The thesis also analyses individual Shembe member‟s experiences and discusses how some members of the Shembe church experience the acceptance of the Shembe religion in South African society. This thesis concludes by trying to make a distinction between intolerance and controversy. -

Reading 1 John in a Zulu Context: Hermeneutical Issues

University of Pretoria READING 1 JOHN IN A ZULU CONTEXT: HERMENEUTICAL ISSUES by Hummingfield Charles Nkosinathi Ndwandwe Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor Divinitatis in the Faculty of Theology Department of New Testament University of Pretoria PRETORIA December 2000 University of Pretoria Abstract This study is an attempt to read 1 John, a document which was conceptualised almost two thousand years ago in a particularly different context from that of Zulu people into which this venture is undertaken. A number of hermeneutical problems are raised by this kind of reading. Chapter eight of this thesis addresses itself to these problems. The present dissertation utilises the sociology of knowledge especially Berger and Luckmann’s theory of the symbolic universe to investigate the possible social scenario of 1 John into which the conceptualisation and crystallisation of the text of 1 John first took place. The investigation has led the researcher into discovering the abundance of family language and common social conventions relating to family, which the author of 1 John found to be useful vehicles for conveying his understanding of the new situation that had come about as a result of the fellowship eventuating from the acceptance of the gospel. The same theory of Berger and Luckmann was used to investigate the African (Zulu) scenario with the view to ascertaining whether some form of congruency could be established between the social symbols identified in 1 John and those obtaining in the Zulu context. To ensure that the results of this investigation applied to Zulu people of this day and age, the researcher conducted field research. -

Scale and Impact of the Illegal Leopard Skin Trade for Traditional Use in Southern Africa

SCALE AND IMPACT OF THE ILLEGAL LEOPARD SKIN TRADE FOR TRADITIONAL USE IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Vincent Norman Naude A thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa Department of Biological Sciences University of Cape Town March 2020 University of Cape Town Dr Jacqueline M. Bishop Dr Guy A. Balme Prof. M. Justin O’Riain Supervisor Co-supervisor Co-supervisor ICWild Panthera ICWild University of Cape Town University of Cape Town University of Cape Town Rondebosch 7701 Rondebosch 7701 Rondebosch 7701 South Africa South Africa South Africa [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town For Indiana and all those with wild hearts… DECLARATION I Vincent Norman Naude, hereby declare that the work on which this thesis is based is my original work (except where acknowledgements indicate otherwise) and that neither the whole work nor any part of it has been, is being, or is to be submitted for another degree in this or any other university. My MSc was upgraded to a PhD by the Doctoral Degrees Board of the University of Cape Town in February 2017 and has been included in this thesis and described as such. -

The Umnazaretha of the Nazareth Baptist Church in South Africa

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1996 White Robes For Worship: The Umnazaretha of the Nazareth Baptist Church In South Africa Karen H. Brown Indiana University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Brown, Karen H., "White Robes For Worship: The Umnazaretha of the Nazareth Baptist Church In South Africa" (1996). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 878. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/878 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WHITE ROBES FOR WORSHIP: THE UMNAZARETHA OF THE NAZARETH BAPTIST CHURCH IN SOUTH AFRICA Karen H. Brown South-eastern Africa was a major locus of Christian missionary activity during the 19th and early 20th century and some dozen or more denominations took to the mission field among the Zulus. 1 A Zulu man, Isaiah Shembe (c. 1879-1935) was one of many attracted to the Christian faith. His independent and questioning nature, however, did not allow him to fit into the structure of the white-led missions. Shembe founded his own church, the Nazareth Baptist Church (lbandla lamaNazaretha), around 1910. Its beliefs and practices are based on a unique synthesis of Christian, largely Old Testament, dogma and Zulu traditional beliefs. In addition to its specific theology, the Church is well known for the charismatic family, the Shembes, who have led it for some 85 years and the characteristic uniforms for worship and dance worn by its followers. -

The Zion Christian Church and the Apartheid Regime

THE ZION CHRISTIAN CHURCH AND THE APARTHEID REGIME Matthew Schoffeleers "If the ANC leadership wants to win mass support it may be better advised to work on the Zion Christian Church hierarchy than to dismiss this enormous group as a relic of political underdevelopment."1 Introduction On Easter Sunday, April 7, 1985, State President P.W. Botha addressed a crowd of over two million black South Africans at the headquarters of the Zion Christian Church (ZCC), which was then celebrating its 75th anniversary.2 The festivities took place at Zion City, Moria, about forty-eight kilometres from Pietersburg in the Northern Transvaal. The presidential couple arrived by helicopter and the head of the church, the Right Reverend Bishop Barnabas Lekganyane, went to the landing pad in an extra-long American limousine to greet his visitors. The President was given an opportunity to address the congregation, and Bishop Lekganyane presented him with a scroll conferring on him the first-ever honorary citizenship of Moria, "in appreciation of his efforts to spread peace and love, and to prove the high esteem in which he is held". The President returned the compliment by giving the bishop a leather-bound Afrikaans Bible. In his speech, which was frequently interrupted by applause, Botha warned his audience against "the powers of darkness and the messengers of evil", terms which were interpreted by sections of the press as referring to the African National Congress and its supposed communist supporters (The Times, April 8, 1985). Citing St. Paul's Letter to the Romans, he declared, 42 The Zion Christian church every man is subject to civil authorities. -

The Role of Isaiah Shembe's Nazarite Cidjrch Focusing on The

THE ROLE OF ISAIAH SHEMBE'S NAZARITE CIDJRCH FOCUSING ON THE HEALING AND CARINGMINISTRY TO PEOPLE UVINGWITH HIV/AIDS AND THEIR FAMll.-IES IN GREATER PIETERMARITZBURG AREA IN KWAZULU- NATAL. BY THlllVHALI NATHANIEL MADIMA [ B.A, UE.D( UNIVEN), B.T H. (HONS),NATAL. DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR TIIE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF TIIEOLOGYIN TIffi FACULTY OF HUMAN AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES, IN THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF NATAL, PIETERMARITZBURG. SEPTEMBER 2003. SUPERVISOR: PROF. MP. MOILA TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE DECLARATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 11. DEDICATION 111. ABBREVIATIONS IV ABSTRACT v. CHAPTER ONE : INTRODUCTION 1. CHAPTER TWO: AN OVERVIEW OF THE HIV/AIDS EPIDEMIOLOGY IN KWAZULU- NATAL. 2.1 Introduction 8. 2.2. An overview ofthe HIV/AIDS epidemiology in South Africa 8. 2.2. 1. The origin ofHIV/AIDS 9. 2..2.2. Mode oftransmission 9. 2.2.3. What does it mean to be HIV positive? 10. 2. 3. Spiritual effects ofHIV infection on the victim 11. 2. 4 .People's myths about HIV/AIDS 14. 2. 5. The church's response on HIV/AIDS in Kwazulu- Natal 18. 2. 6. Conclusion. 21. CHAPTER THREE: THE THEOLOGY OF HEALING AND HIV /AIDS. 3.1. Introduction. 22. 3.2. Developing the theology ofhealing 22. 3. 2 .1. Healing in the Old Testament 23. 3 . 2. 2. Healing in the ancient world. 24. 3 .2 . 3. Healing in the Jewish culture ofthe 1st century. 25. 3.2.4. The healing ministry ofJesus. 26 3.2 5. Healing in the history ofthe church. 27. 3.2. 5. 1 Healing before the Reformation period. -

Journal for the Study of Religion: Essays in Honour of David Chidester

Journal for the Study of Religion: Essays in honour of David Chidester Editorial Introduction Materializing Religion: Essays in Honor of David Chidester Johan M. Strijdom [email protected] Lee-Shae S. Scharnick-Udemans [email protected] In his recent Religion: Material dynamics, David Chidester (2018) selected a number of key concepts that have preoccupied him during his forty years of studying religion. Having contributed to critiques of the concept of religion as a modern Western imperial and colonial invention, Chidester is intensely aware of the legacy of the term but has nevertheless employed it productively as an analytical term. If the academic study of religion, as heir of a Protestant bias, used to study beliefs, Chidester has been a pioneer in foregrounding material terms as a corrective in the study of religion, crediting Marx as crucial ancestor of this approach for his insight into the material basis of religion. The terms essayed in this book, considered under the title material dynamics, were selected by Chidester for the real, practical consequences they have had in the world, and were grouped under three sections: Categories, formations, and circulations. Under categories, Chidester challenges us to reconsider a number of basic analytical categories in the academic study of religion: The prioritization of ideas over matter in imperial studies of religion; the Durkheimian opposition between sacred and profane in light of popular culture in which anything can be made sacred by intensive interpretation and ritualization; sacred time and space as historically contingent constructs that entail exclusions, hierarchies and contestations of ownership; and the crucial importance of the destabilizing Journal for the Study of Religion 31, 2 (2018) 1-6 1 Online ISSN 2413-3027; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a0 Johan M. -

African Zionism and Its Contribution to African Christianity in South Africa

Scriptura 119 (2020:1), pp. 1-16 http://scriptura.journals.ac.za http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/119-1-1768 AFRICAN ZIONISM AND ITS CONTRIBUTION TO AFRICAN CHRISTIANITY IN SOUTH AFRICA Kelebogile Thomas Resane Department of Historical & Constructive Theology University of the Free State Abstract The paper highlights the historical development of African Zionism, with special reference to the four major messianic churches. Socio-political conditions and other factors contributed to the formation of African Zionism. Israel’s nationalist theology of the temple and the John Alexander Dowie’s Zion City concepts played a significant role in influencing the formation of African Zionism. The churches selected for the study are Zion Christian Church, Shembe’s AmaNazaretha, International Pentecost Church, and St John’s Apostolic Faith Mission. The focus is on the spiritual significance of the cultic centre as perceived by these church formations. The reasons for pilgrimages to the centre are elaborated on, and the contribution of these churches to African Christianity are highlighted. Keywords: Zionism; Church; Cultic; Messianic; Worship; Healing Introduction: Israel’s nationalist theology influenced African Zionism The period 597-450 BCE was an era of theological crisis in Israel. Theological trends were syncretic and called for renewal of the fundamentalistic return to the messianic tradition. Three loci that held this nationalist theology were the city, the temple, and the Davidic royal throne. They were the three sacrosanct forces that held the nation together. This paper pays special attention to the cultic centre i.e. the temple. “The nationalist theology was so strong, and so deeply rooted in Israel’s faith, as to be virtually unassailable” (Le Roux 1987:104). -

Lessee Financial Report (2018/2019)

Lessee Financial Report (2018/2019) Annexure C Generated on 5/14/2018 3:10:10 PM Total leases: 1381 Ref No. Lessee Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep 25 Africa Centre - MPUKUNYONI T/A 43.71 43.71 43.71 43.71 48.09 48.09 70 Amafa Akwazulu Natali - MNGOMEZULU T/A 43.71 43.71 43.71 43.71 43.71 43.71 80 Isivuno - N/A 0.09 0.09 0.09 0.09 0.09 0.09 89 Mgodeni Farming Co-operative 907.62 907.62 907.62 907.62 907.62 907.62 170 Coral Reef Lodge CC - MBILA T/A 2248.37 2248.37 2248.37 2248.37 2248.37 2248.37 171 Maranatha Reformed Church - N/A 61.8 61.8 61.8 61.8 61.8 61.8 212 Sodwana Property Development - MBILA 2349.55 2349.55 2349.55 2349.55 2349.55 2349.55 224 Mseleni Housing Association 1125.05 1125.05 1125.05 1125.05 1125.05 1125.05 226 Richmond Municipality - N/A 543.77 543.77 543.77 543.77 543.77 543.77 229 Richmond Municipality - N/A 543.77 543.77 543.77 543.77 543.77 543.77 232 Jozini Tiger Lodge - NTSINDE T/A 14850.88 14850.88 14850.88 14850.88 14850.88 14850.88 237 Zululand Craft Centre Lodge - MBILA T/A 618.08 618.08 618.08 618.08 618.08 618.08 238 Mr M.A.Qwabe - TEMBE T/A 247.41 247.41 247.41 247.41 247.41 272.15 240 Librodi Lodge Share Block - MBILA TA/ 296.79 296.79 296.79 296.79 296.79 296.79 257 Mbazwane Properties (PTY)Ltd - N/A 939.84 939.84 939.84 939.84 939.84 939.84 262 Sodwana Boat Lockers (Pty) Ltd - MBILA T/A 1487.7 1487.7 1636.47 1636.47 1636.47 1636.47 267 Island Rock Pty Ltd - - TEMBE T/A 939.52 939.52 939.52 939.52 939.52 939.52 272 Zamukuzakha Office Complex CC - 168.63 168.63 168.63 168.63 185.5 185.5 VUKUZITHATHE 275 KwaMandende Dist Service - TEMBE T/A 445.18 445.18 445.18 445.18 445.18 445.18 © Copyright 2018 MHP Geospace.