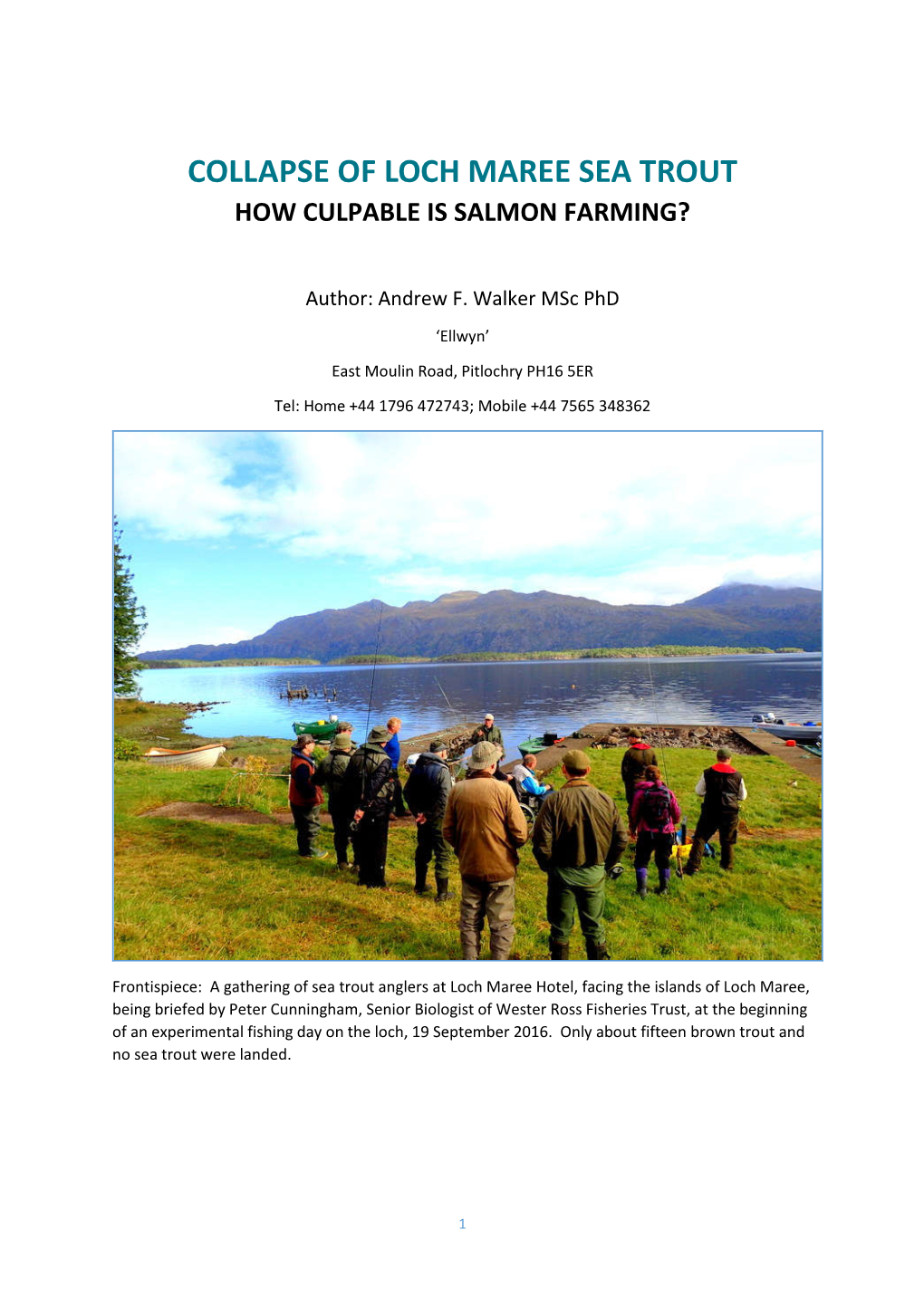

Collapse of Loch Maree Sea Trout How Culpable Is Salmon Farming?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier of Chemical Use on Scottish Salmon Farms (2008-2011)

Dossier of Chemical Use on Scottish Salmon Farms (2008-2011) Based on data obtained from the Scottish Environment Protection Agency via Freedom of Information in July 2012 (available in full online here and read SEPA's data re-use statement online here ). More details online via FishyLeaks Summary: Total chemical use (Cypermethrin, Azamethiphos, Teflubenzuron, Emamectin benzoate & Deltamethrin) on Scottish salmon farms increased by 110% between 2008 and 2011 2008: 188076.07g 2009: 342847.8462g 2010: 373757.8495g 2011: 394630.5414g The alarming rise in chemical use is five times more than the percentage increase in salmon farming production: whilst Scottish farmed salmon production steadily increased by 22% between 2008 and 2011 (up from 128,606 tonnes to 157,385 tonnes) the use of toxic chemicals increased by a shocking 110% (up from 188076.07g to 394630.5414g). In terms of total chemical use (2008-2011), Azamethiphos accounts for over half (55%) with Emamectin benzoate (19%), Teflubenzuron (18%), Deltamethrin (5%) and Cypermethrin (3%). The relative composition of chemical use has changed since 2008 – but the use of Azamethiphos has always remained the largest component. As Cypermethrin use has declined the use of Teflubenzuron has increased to be the 2nd largest in 2011: Almost twice every day for the last four years (2008 to 2011), toxic chemicals were used on salmon farms across Scotland. Chemicals were used on 2,756 occasions with Emamectin benzoate used 1,028 times; Deltamethrin 914; Azamethiphos 487; Cypermethrin 315 and Teflubenzuron -

Quaternary of Scotland the GEOLOGICAL CONSERVATION REVIEW SERIES

Quaternary of Scotland THE GEOLOGICAL CONSERVATION REVIEW SERIES The comparatively small land area of Great Britain contains an unrivalled sequence of rocks, mineral and fossil deposits, and a variety of landforms that span much of the earth's long history. Well-documented ancient volcanic episodes, famous fossil sites, and sedimentary rock sections used internationally as comparative standards, have given these islands an importance out of all proportion to their size. These long sequences of strata and their organic and inorganic contents, have been studied by generations of leading geologists thus giving Britain a unique status in the development of the science. Many of the divisions of geological time used throughout the world are named after British sites or areas, for instance the Cambrian, Ordovician and Devonian systems, the Ludlow Series and the Kimmeridgian and Portlandian stages. The Geological Conservation Review (GCR) was initiated by the Nature Conservancy Council in 1977 to assess, document, and ultimately publish accounts of the most important parts of this rich heritage. The GCR reviews the current state of knowledge of the key earth-science sites in Great Britain and provides a firm basis on which site conservation can be founded in years to come. Each GCR volume describes and assesses networks of sites of national or international importance in the context of a portion of the geological column, or a geological, palaeontological, or mineralogical topic. The full series of approximately 50 volumes will be published by the year 2000. Within each individual volume, every GCR locality is described in detail in a self- contained account, consisting of highlights (a precis of the special interest of the site), an introduction (with a concise history of previous work), a description, an interpretation (assessing the fundamentals of the site's scientific interest and importance), and a conclusion (written in simpler terms for the non-specialist). -

Scotland Vacation

WALKINGWALKING HOLIDAYHOLIDAY ININ SCOTLANDSCOTLAND An East-West Traverse fromfrom thethe HighlandsHighlands toto thethe IslandsIslands In what may seem like an empty wilderness to the fi rst-time visitor, life is rich and abundant in Scotland, the largest wilderness area re- “The Grand Dame” of Women’s maining in the U.K. and in Europe. Storm-wrapped mountains, ver- Adventure Travel Since 1982 dant stone-walled hills, unspoiled sand beaches, highlands bathed 2014 ~ Celebrating 32 Years! in northern light, wild and vast wind-swept lochs, fuschia heather DATES on a balmy afternoon.....this is Scotland, the world’s undiscovered June 20 - 29, 2014 secret. Dramatic, wild, and curiously unknown, it is also the home COST of a fi ercely independent people, the Scots. $4,295 from Edinburgh, Scotland ($800 deposit) For AdventureWomen’s fi fth trip to this fascinating destination RATING and our 2014 Walking Holiday in Scotland, we have gathered the Moderate perfect combination of activities: hiking and exploring the diverse landscapes of Scotland (some of which are accessible only by ACTIVITIES Hiking, Walking, Cultural Exploration, Sight- water); enjoying the company of a knowledgeable, Scottish natu- seeing, Natural History, Boat Rides, Wildlife ralist-guide; experiencing fi rst-hand the history and culture of the Excursions, Photography, Whiskey Tasting self-reliant Scots; and even tasting the “water of life,” Scotland’s term for their fi nest whiskey! MAIN ATTRACTIONS • Explore three of Scotland’s distinct Our walking holiday hikes take us on an exploration of three of Scot- regions: Central Perthshire, the land’s distinct regions: Central Perthshire, the Western Highlands, Western Highlands, and the Inner Hebrides islands. -

The River Tay - Its Silvery Waters Forever Linked to the Picts and Scots of Clan Macnaughton

THE RIVER TAY - ITS SILVERY WATERS FOREVER LINKED TO THE PICTS AND SCOTS OF CLAN MACNAUGHTON By James Macnaughton On a fine spring day back in the 1980’s three figures trudged steadily up the long climb from Glen Lochy towards their goal, the majestic peak of Ben Lui (3,708 ft.) The final arête, still deep in snow, became much more interesting as it narrowed with an overhanging cornice. Far below to the West could be seen the former Clan Macnaughton lands of Glen Fyne and Glen Shira and the two big Lochs - Fyne and Awe, the sites of Fraoch Eilean and Dunderave Castle. Pointing this out, James the father commented to his teenage sons Patrick and James, that maybe as they got older the history of the Clan would interest them as much as it did him. He told them that the land to the West was called Dalriada in ancient times, the Kingdom settled by the Scots from Ireland around 500AD, and that stretching to the East, beyond the impressively precipitous Eastern corrie of Ben Lui, was Breadalbane - or upland of Alba - part of the home of the Picts, four of whose Kings had been called Nechtan, and thus were our ancestors as Sons of Nechtan (Macnaughton). Although admiring the spectacular views, the lads were much more keen to reach the summit cairn and to stop for a sandwich and some hot coffee. Keeping his thoughts to himself to avoid boring the youngsters, and smiling as they yelled “Fraoch Eilean”! while hurtling down the scree slopes (at least they remembered something of the Clan history!), Macnaughton senior gazed down to the source of the mighty River Tay, Scotland’s biggest river, and, as he descended the mountain at a more measured pace than his sons, his thoughts turned to a consideration of the massive influence this ancient river must have had on all those who travelled along it or lived beside it over the millennia. -

January 2021 Newsletter

Scottish Heritage USA NEWSLETTER JANUARY 2021 Vikings leading the Hogmanay Torchlight Parade, Edinburgh ISSUE #1-2021 HAPPY NEW YEAR & HAPPY HOGMANAY! H OGMANAY may be Scotland’s New Year celebration, but it lasts three to five days with unusual, weird and wild H traditions. It starts on Christmas with the Edinburgh Torchlight Parade and is all downhill from there! Look to Scotland to find the best, most spectacular fire festivals in the UK. Combine the primitive impulse to light up the long nights (the ancient idea that fire purifies and chases away evil spirits) and the natural Scottish impulse to party to the wee small hours and you end up with some of the most dazzling and daring midwinter celebrations in Europe. At one time, most Scottish towns celebrated the New Year with huge bonfires and torchlight processions. Many have disappeared, but those that are left are real Site where the horde was found humdingers. Here are the five of the best winter fire festivals in Scotland: STONEHAVEN FIRE FESTIVAL: Strong Scots dare-devils parade through the town on New Year's Eve swinging 16-pound balls of fire around themselves and over their heads. Each "swinger" has his or her own secret recipe for creating the fireball and keeping it lit. Thousands come to watch this famous event on the North Sea, south of Aberdeen. It all gets underway before midnight with bands of pipers and wild drumming. Then a lone piper, playing Scotland the Brave, leads the pipers into town. At the stroke of midnight, they raise their flaming balls over their heads and begin to swing and twirl them, showering the street, themselves and usually the 12,000 strong crowd, with sparks. -

Sanitary Survey Report Loch Ewe and Loch Thurnaig RC-142 April 2015

Scottish Sanitary Survey Report Sanitary Survey Report Loch Ewe and Loch Thurnaig RC-142 April 2015 Loch Ewe and Loch Report Title Thurnaig Sanitary Survey Report Project Name Scottish Sanitary Survey Food Standards Agency Client/Customer Scotland Cefas Project Reference C6316A Document Number C6316A_2014_25 Revision V1.0 Date 23/04/2015 Revision History Revision Date Pages revised Reason for revision number Id2 20/02/2015 - Internal draft for review V0.1 24/02/2015 All Draft for external consultation Amended in accordance with V1.0 23/04/2015 9,16,17 comments received during external consultation Name Position Date Jessica Larkham, Frank Cox, Scottish Sanitary Survey Author 23/04/2015 Liefy Hendrikz Team Principal Shellfish Checked Ron Lee 23/04/2015 Hygiene Scientist Group Manager, Food Approved Michelle Price-Hayward 24/04/2015 Safety This report was produced by Cefas for its Customer, the Food Standards Agency in Scotland, for the specific purpose of providing a sanitary survey as per the Customer’s requirements. Although every effort has been made to ensure the information contained herein is as complete as possible, there may be additional information that was either not available or not discovered during the survey. Cefas accepts no liability for any costs, liabilities or losses arising as a result of the use of or reliance upon the contents of this report by any person other than its Customer. Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Weymouth Laboratory, Barrack Road, The Nothe, Weymouth DT4 8UB. Tel 01305 206 600 www.cefas.gov.uk Loch Ewe and Loch Thurnaig Sanitary Survey V1.0 23/04/2015 i of 76 Report Distribution – Loch Ewe and Loch Thurnaig Date Name Agency Joyce Carr Scottish Government David Denoon SEPA Douglas Sinclair SEPA Hazel MacLeod SEPA Fiona Garner Scottish Water Alex Adrian Crown Estate Alan Yates The Highland Council Bill Steven The Highland Council Jane Grant Harvester Partner Organisations The hydrographic assessment and the shoreline survey and its associated report were undertaken by SRSL, Oban. -

Scotland's Geodiversity, Provides a Source of Basic Raw Materials: Raw Basic of Source a Provides Geodiversity, Scotland's

ROCKS,FOSSILS, LANDFORMS AND SOILS AND LANDFORMS ROCKS,FOSSILS, Cover photograph:Glaciatedmountains,CoireArdair,CreagMeagaidh. understanding. e it and promote its wider its promote and it e conserv to taken being steps the and it upon pressures the heritage, Earth Scotland's of diversity the illustrates leaflet This form the foundation upon which plants, animals and people live and interact. interact. and live people and animals plants, which upon foundation the form he Earth. They also They Earth. he t of understanding our in part important an played have soils and landforms fossils, rocks, Scotland's surface. land the alter the landscapes and scenery we value today, how different life-forms have evolved and how rivers, floods and sea-level changes a changes sea-level and floods rivers, how and evolved have life-forms different how today, value we scenery and landscapes the re continuing to continuing re CC5k0309 mates have shaped have mates cli changing and glaciers powerful volcanoes, ancient continents, colliding how of story wonderful a illustrates It importance. Printed on environmentally friendly paper friendly environmentally on Printed nternational i and national of asset heritage Earth an forms and istence, ex Earth's the of years billion 3 some spanning history, geological For a small country, Scotland has a remarkable diversity of rocks, fossils, landforms and soils. This 'geodiversity' is the res the is 'geodiversity' This soils. and landforms fossils, rocks, of diversity remarkable a has Scotland country, small a For ult of a rich and varied and rich a of ult Leachkin Road, Inverness, IV3 8NW. Tel: 01463 725000 01463 Tel: 8NW. -

Celtic Tours 2022 Brochure

TRIED AND TRUE SINCE 1972 – We are proud of the relationships we have earned over the years with our dedicated travel advisors, and we will promise to continue to bring you the best in service, products, and value. VALUE – Time and time again our tours and pack- ages offer more value for your clients. We have built long and strong relationships with our Irish suppli- ers, allowing us to package our tours at the best prices and inclusions. Call us for your customer tour requests and give us the opportunity to provide you with Celtic Value! 100% CUSTOMER SERVICE – Celtic Tours is driven by providing the best customer service to you, so you can relax and have piece of mind when booking with us. Our agents have a wealth of knowledge and are at your service to help you navigate through putting the perfect Irish vacation together for your clients. TRUST – You know when you are booking with Celtic Tours you are booking with a financially sound and secure company. A fiscally responsible company since 1972! We are also proud members of the United States Tour Operators Association (USTOA). Protecting you and your customers. NO HIDDEN FEES – At Celtic Tours, we do not want to surprise your clients with extras and add-ons. All touring and meals as noted on the itinerary are included. Our group arrival and departure transfers THE are always included no matter if you book air & land or land only with us (note: transfers are scheduled for CELTIC TOURS specific times.) EARN MORE – We know how hard travel agents work, and we want you rewarded. -

Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey August 2019

Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey August 2019 The general public’s perceptions of Scotland’s National Nature Reserves Published: December 2019 People and Places Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House Leachkin Road Inverness IV3 8NW For further information please contact [email protected] 1. Introduction The Scottish Nature Omnibus (SNO) is a survey of the adult population in Scotland which now runs on a biennial basis. It was first commissioned by SNH in 2009 to measure the extent to which the general public is engaged with SNH and its work. Seventeen separate waves of research have been undertaken since 2009, each one based on interviews with a representative sample of around 1,000 adults living in Scotland; interviews with a booster sample of around 100 adults from ethnic minority groups are also undertaken in each survey wave to enable us to report separately on this audience. The SNO includes a number of questions about the public’s awareness of and visits to National Nature Reserves (see Appendix). This paper summarises the most recent findings from these questions (August 2019), presenting them alongside the findings from previous waves of research. Please note that between 2009 and 2015 the SNO was undertaken using a face to face interview methodology. In 2017, the survey switched to an on-line interview methodology, with respondents sourced from members of the public who had agreed to be part of a survey panel. While the respondent profile and most question wording remained the same, it should be borne in mind when comparing the 2017 and 2019 findings with data from previous years that there may be differences in behaviour between people responding to a face to face survey and those taking part in an online survey that can impact on results. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Protected Landscapes: the United Kingdom Experience

.,•* \?/>i The United Kingdom Expenence Department of the COUNTRYSIDE COMMISSION COMMISSION ENVIRONMENT FOR SCOTLAND NofChern ireianc •'; <- *. '•ri U M.r. , '^M :a'- ;i^'vV r*^- ^=^l\i \6-^S PROTECTED LANDSCAPES The United Kingdom Experience Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from UNEP-WCIVIC, Cambridge http://www.archive.org/details/protectedlandsca87poor PROTECTED LANDSCAPES The United Kingdom Experience Prepared by Duncan and Judy Poore for the Countryside Commission Countryside Commission for Scotland Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Published for the International Symposium on Protected Landscapes Lake District, United Kingdom 5-10 October 1987 * Published in 1987 as a contribution to ^^ \ the European Year of the Environment * W^O * and the Council of Europe's Campaign for the Countryside by Countryside Commission, Countryside Commission for Scotland, Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources © 1987 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Avenue du Mont-Blanc, CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Additional copies available from: Countryside Commission Publications Despatch Department 19/23 Albert Road Manchester M19 2EQ, UK Price: £6.50 This publication is a companion volume to Protected Landscapes: Experience around the World to be published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, -

Guidance for All Water Users

Using Inland Water Responsibly: Guidance for All Water Users Developed in Partnership with This guidance was developed with nancial support from Scottish Natural Heritage This document has been endorsed by the following organisations: The Association of Salmon Fishery Boards Atlantic Salmon Trust The British Association for Shooting and Conservation British Waterways Scotland Royal Yachting Association Scottish Advisory Panel for Outdoor Education Scottish Anglers National Association Scottish Rowing sportscotland Contents Introduction Section1 - Legislative context Part 1 Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 Scottish Outdoor Access Code Rights of Navigation Section 2 - Inland Water Use Types of recreational activities Types of angling activities Informal Camping (as part of a paddling or angling trip) Glossary of terms Fishing, stalking and shooting seasons Section 3 - Sharing the Water General considerations on land and water Face to face communication Communication through signage Section 4 - Considerations for larger groups/intensive use Enhanced communication and co-operative working Provision of facilities Local agreements Users’ groups Section 5 - Indigenous species (and threats to them) The Atlantic Salmon Gyrodactlylus salaris North American Signal Crayfish Other biosecurity considerations Section 6 - Useful Contacts Appendix 1: Shooting and Stalking Seasons Using Inland Water Responsibly: Guidance for all water users 1 Introduction This Guidance is intended to assist all water users to share inland water in Scotland in such a way