Active Changes in Monolithic Manliness the Case of the 2004 NHL Lockout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011-12 Rochester Americans Media Guide (.Pdf)

Rochester Americans Table of Contents Rochester Americans Personnel History Rochester Americans Staff Directory........................................................................................4 All-Time Records vs. Current AHL Clubs ..........................................................................203 Amerks 2011-12 Schedule ............................................................................................................5 All-Time Coaches .........................................................................................................................204 Amerks Executive Staff ....................................................................................................................6 Coaches Lifetime Records ......................................................................................................205 Amerks Hockey Department Staff ..........................................................................................10 Presidents & General Managers ...........................................................................................206 Amerks Front Office Personnel ................................................................................................ 17 All-Time Captains ..........................................................................................................................207 Affiliation Timeline ........................................................................................................................208 Players Amerks Firsts & Milestones -

Weekend with a Legend

Weekend with a Legend Participate in the Ultimate Hockey Fan Experience and spend the weekend playing with some of hockey’s greatest Legends. This experience will allow you to draft your favorite hockey Legend to become apart of your team for the weekend. This means they will play in all of your scheduled tournament games, hang-out in the dressing room sharing stories of their careers, and take in the nightlife with the team. All you have to do is select a player from the list below or request a player that you don’t see and we will do our best to accommodate your group with the 100+ other Legends that have participated in our events. Golden Legends- starting @ $365cdn/ per person (based on a team of 20). $7,300/ per team. Al Iafrate (Toronto Maple Leafs) Gary Leeman (Toronto Maple Leafs) Chris “Knuckles” Nilan (Montreal Canadiens) John Scott (Arizona Coyotes) Bob Sweeney (Boston Bruins) Natalie Spooner (Canadian Olympic Team) Andrew Raycroft (Toronto Maple Leafs) Ron Duguay (New York Rangers) Darren Langdon (New York Rangers) Colton Orr (Toronto Maple Leafs) Dennis Maruk (Washington Capitals) Chris Kotsopoulos (Hartford Whalers) John Leclair (Philadelphia Flyers) Colin White (New Jersey Devils) Kevin Stevens (Pittsburgh Penguins) Shane Corson (Toronto Maple Leafs) Mike Krushelnyski (Edmonton Oilers) Theo Fleury (Calgary Flames) Many More………. Platinum Legends- starting @ $665cdn/ per person (based on a team of 20). $20,000cdn/ per team. Ray Bourque (Boston Bruins) Wendel Clark (Toronto Maple Leafs) Guy Lafleur (Coach) (Montreal Canadiens) Bryan Trottier (New York Islanders) Steve Shutt (Montreal Canadiens) Bernie Nicholls (LA Kings) Many More………. -

Press Clips December 5, 2013 Rangers-Sabres Preview Associated Press December 4, 2013

Buffalo Sabres Daily Press Clips December 5, 2013 Rangers-Sabres Preview Associated Press December 4, 2013 If there was the slightest bit of doubt that Henrik Lundqvist was the clear-cut No. 1 goaltender for the New York Rangers, it has been eliminated this week. A day after agreeing to a seven-year contract extension, Lundqvist is likely to return to the ice after a rare two-game stretch on the bench as New York desperately tries to get some momentum going Thursday night against the Buffalo Sabres. "It was never an option for me to leave this club," Lundqvist said after the new deal was announced. "I really want to win the Cup here in New York." This trip to Buffalo precedes a nine-game homestand which will take the Rangers (14-14-0) through Christmas, a stretch Lundqvist would surely welcome. He has a 1.69 goals-against average at Madison Square Garden compared to 3.28 on the road. He hasn't been in net at MSG since Nov. 19 because New York's only two home games since then - also its two most recent games - were started by Cam Talbot even though Lundqvist was healthy. Talbot had been outplaying Lundqvist, going 6-1-0 with a 1.49 GAA through November while the five-time Vezina Trophy finalist was 8-11-0 with a career-worst 2.51 GAA. However, Talbot came back down to Earth on Monday, giving up four goals on 29 shots in a 5-2 loss to Winnipeg. Two days later, the team announced it had agreed to terms on the new deal with Lundqvist worth a reported $59.5 million. -

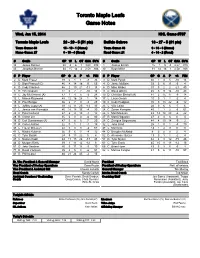

Toronto Maple Leafs Game Notes

Toronto Maple Leafs Game Notes Wed, Jan 15, 2014 NHL Game #707 Toronto Maple Leafs 23 - 20 - 5 (51 pts) Buffalo Sabres 13 - 27 - 5 (31 pts) Team Game: 49 15 - 10 - 1 (Home) Team Game: 46 9 - 13 - 3 (Home) Home Game: 27 8 - 10 - 4 (Road) Road Game: 21 4 - 14 - 2 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 34 James Reimer 20 8 6 1 3.08 .918 1 Jhonas Enroth 15 1 9 4 2.57 .913 45 Jonathan Bernier 34 15 14 4 2.58 .926 30 Ryan Miller 31 12 18 1 2.58 .928 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Mark Fraser 19 0 1 1 -8 33 3 D Mark Pysyk 40 1 4 5 -10 14 3 D Dion Phaneuf (C) 46 4 14 18 9 65 4 D Jamie McBain 33 3 6 9 -5 4 4 D Cody Franson 46 2 19 21 -11 18 6 D Mike Weber 31 0 2 2 -21 40 8 D Tim Gleason 22 0 2 2 -10 14 9 C Steve Ott (C) 45 5 9 14 -16 43 11 C Jay McClement (A) 47 1 4 5 -2 24 10 D Christian Ehrhoff (A) 44 2 15 17 -9 18 12 L Mason Raymond 48 12 16 28 1 14 17 L Linus Omark 10 0 1 1 -2 4 15 D Paul Ranger 36 2 7 9 -8 28 19 C Cody Hodgson 35 9 13 22 -9 12 19 L Joffrey Lupul (A) 39 14 11 25 -13 35 23 L Ville Leino 28 0 6 6 -7 6 21 L James van Riemsdyk 46 18 18 36 -4 30 24 C Zenon Konopka 40 1 1 2 -6 61 24 C Peter Holland 27 6 4 10 -1 12 26 L Matt Moulson 43 14 14 28 -6 22 28 R Colton Orr 35 0 0 0 -6 80 27 R Matt D'Agostini 27 2 4 6 0 4 36 D Carl Gunnarsson (A) 47 0 6 6 7 20 28 C Zemgus Girgensons 44 4 10 14 -9 2 37 R Carter Ashton 22 0 1 1 -1 19 32 L John Scott 25 1 0 1 -8 70 38 L Frazer McLaren 22 0 0 0 -3 67 37 L Matt Ellis 13 1 2 3 0 0 41 L Nikolai Kulemin 36 5 6 11 -4 12 44 D Brayden McNabb 9 0 0 0 2 4 42 C Tyler Bozak 24 9 13 22 5 4 52 D Alexander Sulzer 13 0 1 1 -2 4 43 C Nazem Kadri 44 11 15 26 -13 43 57 D Tyler Myers 42 4 8 12 -15 46 44 D Morgan Rielly 39 1 11 12 -12 8 63 C Tyler Ennis 45 10 8 18 -12 16 51 D Jake Gardiner 46 3 11 14 -3 10 65 C Brian Flynn 43 3 3 6 -5 4 71 R David Clarkson 35 3 5 8 -6 51 82 L Marcus Foligno 41 5 6 11 -10 57 81 R Phil Kessel 48 21 24 45 -2 15 Sr. -

Check to the Head: the Tragic Death of NHL Enforcer Derek Boogaard and the NHL's Negligence - How Enforcers Are Treated As Second-Class Employees

Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 7 1-1-2015 Check to the Head: The Tragic Death of NHL Enforcer Derek Boogaard and the NHL's Negligence - How Enforcers Are Treated as Second-Class Employees Melanie Romero Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Melanie Romero, Check to the Head: The Tragic Death of NHL Enforcer Derek Boogaard and the NHL's Negligence - How Enforcers Are Treated as Second-Class Employees, 22 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 271 (2015). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol22/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. 36293-vls_22-1 Sheet No. 144 Side A 04/07/2015 08:38:16 \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\22-1\VLS107.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-MAR-15 13:14 Romero: Check to the Head: The Tragic Death of NHL Enforcer Derek Boogaar CHECK TO THE HEAD: THE TRAGIC DEATH OF NHL ENFORCER, DEREK BOOGAARD, AND THE NHL’S NEGLIGENCE –HOW ENFORCERS ARE TREATED AS SECOND-CLASS EMPLOYEES “To distill this to one sentence, you take a young man, you sub- ject him to trauma, you give him pills for that trauma, he be- comes addicted to those pills, you promise to treat him for that addiction, and you fail.”1 I. -

Buffalo Sabres Game Notes

Buffalo Sabres Game Notes Fri, Nov 15, 2013 NHL Game #284 Buffalo Sabres 4 - 15 - 1 (9 pts) Toronto Maple Leafs 11 - 6 - 1 (23 pts) Team Game: 21 1 - 8 - 1 (Home) Team Game: 19 6 - 2 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 11 3 - 7 - 0 (Road) Road Game: 11 5 - 4 - 1 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 1 Jhonas Enroth 7 1 4 1 2.69 .916 34 James Reimer 8 4 2 0 2.30 .942 30 Ryan Miller 14 3 11 0 3.28 .916 45 Jonathan Bernier 12 7 4 1 2.05 .939 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 3 D Mark Pysyk 20 0 2 2 -5 4 2 D Mark Fraser 5 0 0 0 1 18 4 D Jamie McBain 12 1 3 4 -4 2 3 D Dion Phaneuf (C) 18 2 5 7 9 16 8 C Cody McCormick 16 1 4 5 -2 34 4 D Cody Franson 18 0 10 10 -2 6 9 C Steve Ott (C) 20 2 3 5 -8 28 11 C Jay McClement (A) 17 0 1 1 1 10 10 D Christian Ehrhoff (A) 19 0 4 4 -3 8 12 L Mason Raymond 18 6 6 12 1 2 19 C Cody Hodgson 20 7 8 15 -5 6 15 D Paul Ranger 18 1 4 5 4 16 20 D Henrik Tallinder 15 2 1 3 -6 14 19 L Joffrey Lupul (A) 16 8 4 12 -3 16 21 R Drew Stafford 20 2 4 6 -5 8 21 L James van Riemsdyk 16 7 6 13 6 16 22 L Johan Larsson 17 0 1 1 -2 13 22 C Jerred Smithson 3 0 0 0 0 2 23 L Ville Leino 8 0 1 1 -3 2 26 D John-Michael Liles 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 C Mikhail Grigorenko 15 2 1 3 -3 2 28 R Colton Orr 16 0 0 0 -2 51 26 L Matt Moulson 18 8 9 17 2 6 36 D Carl Gunnarsson 18 0 1 1 2 8 28 C Zemgus Girgensons 19 1 4 5 -1 2 37 R Carter Ashton 12 0 1 1 2 12 32 L John Scott 7 0 0 0 -3 19 38 L Frazer McLaren 7 0 0 0 0 21 55 D Rasmus Ristolainen 17 1 0 1 -5 4 40 R Troy Bodie 9 0 2 2 0 5 57 D Tyler Myers 20 1 3 4 -9 31 41 L Nikolai Kulemin 6 0 2 2 1 4 61 D Nikita Zadorov 7 1 0 1 -4 4 43 C Nazem Kadri 18 5 9 14 -1 28 63 C Tyler Ennis 20 2 4 6 -7 8 44 D Morgan Rielly 15 0 6 6 -4 6 65 C Brian Flynn 20 2 1 3 -4 0 51 D Jake Gardiner 18 0 3 3 2 6 78 R Corey Tropp 5 0 1 1 -6 0 71 R David Clarkson 8 0 1 1 -2 23 82 L Marcus Foligno 17 2 4 6 -9 18 81 R Phil Kessel 18 10 9 19 5 13 Owner Terry Pegula Sr. -

Toronto Maple Leafs

NATIONAL POST NHL PREVIEW Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment | Owner Brendan Shanahan | President Senior VP, general manager Head coach Dave Nonis Randy Carlyle $1.15B 19,446 Assistant general manager Assistant coaches Forbes 2013 valuation Average 2013-14 attendance Kyle Dubas Peter Horachek NHL rank: First NHL rank: Sixth Assistant to the general mgr. Steve Spott Brandon Pridham Chris Dennis Dir. of player development Rick St. Croix (goalies) Current 2014-15 payroll Jim Hughes Scouting directors NHL rank: Sixth Dir., hockey/scouting admin. Dave Morrison (amateur) $69.25M *Must be under $69M by today Reid Mitchell Steve Kasper (pro) 2014-15 TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS YEARBOOK FRANCHISE OUTLOOK RECORDS 2013-14 | 84 points (38-36-8), sixth in Atlantic | 2.71 goals per game (14th); 3.07 goals allowed per game (26th) The poster boy for the 2014-15 ver- 0.92 5-on-5 goal ratio (22nd) | 19.8% power play (6th); 78.4% penalty kill (28th) | –8.0 shot differential per game (T29th) Season records are from beginning sion of the Toronto Maple Leafs is 2013-14 post-season | Did not qualify of Original Six era (1942-present) a baby-faced forward who stands 5-foot-8 and 167 pounds. He can THE FRANCHISE INDEX: THE LEAFS SINCE THE ORIGINAL SIX ERA GAMES PLAYED, CAREER skate and has the skill to play on the NUMBER OF NUMBER OF WON STANLEY LOST STANLEY LOCKOUT 1. George Armstrong | 1949-71 1,187 second line. He is precisely the kind POINTS WON GAMES PLAYED CUP FINAL CUP FINAL 2. Tim Horton | 1949-70 1,185 of player who, in previous years, 3. -

PLAYOFF HISTORY and RECORDS RANGERS PLAYOFF Results YEAR-BY-YEAR RANGERS PLAYOFF Results YEAR-BY-YEAR

PLAYOFF HISTORY AnD RECORDS RANGERS PLAYOFF RESuLTS YEAR-BY-YEAR RANGERS PLAYOFF RESuLTS YEAR-BY-YEAR SERIES RECORDS VERSUS OTHER CLUBS Year Series Opponent W-L-T GF/GA Year Series Opponent W-L-T GF/GA YEAR SERIES WINNER W L T GF GA YEAR SERIES WINNER W L T GF GA 1926-27 SF Boston 0-1-1 1/3 1974-75 PRE Islanders 1-2 13/10 1927-28 QF Pittsburgh 1-1-0 6/4 1977-78 PRE Buffalo 1-2 6/11 VS. ATLANTA THRASHERS VS. NEW YORK ISLANDERS 2007 Conf. Qtrfinals RANGERS 4 0 0 17 6 1975 Preliminaries Islanders 1 2 0 13 10 SF Boston 1-0-1 5/2 1978-79 PRE Los Angeles 2-0 9/2 Series Record: 1-0 Total 4 0 0 17 6 1979 Semifinals RANGERS 4 2 0 18 13 1981 Semifinals Islanders 0 4 0 8 22 F Maroons 3-2-0 5/6 QF Philadelphia 4-1 28/8 VS. Boston BRUINS 1982 Division Finals Islanders 2 4 0 20 27 1928-29 QF Americans 1-0-1 1/0 SF Islanders 4-2 18/13 1927 Semifinals Bruins 0 1 1 1 3 1983 Division Finals Islanders 2 4 0 15 28 SF Toronto 2-0-0 3/1 F Montreal 1-4 11/19 1928 Semifinals RANGERS 1 0 1 5 2 1984 Div. Semifinals Islanders 2 3 0 14 13 1929 Finals Bruins 0 2 0 1 4 1990 Div. Semifinals RANGERS 4 1 0 22 13 F Boston 0-2-0 1/4 1979-80 PRE Atlanta 3-1 14/8 1939 Semifinals Bruins 3 4 0 12 14 1994 Conf. -

Toronto Maple Leafs

Toronto Maple Leafs From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "Leafs" redirects here. For other uses, see Leafs (disambiguation). For other uses, see Toronto Maple Leafs (disambiguation). Toronto Maple Leafs 2010±11 Toronto Maple Leafs season Conference Eastern Division Northeast Founded 1917 Toronto Blueshirts 1917±18 Toronto Arenas 1918±19 History Toronto St. Patricks 1919 ± February 14, 1927 Toronto Maple Leafs February 14, 1927 ± present Home arena Air Canada Centre City Toronto, Ontario Blue and white Colours Leafs TV Rogers Sportsnet Ontario Media TSN CFMJ (640 AM) Maple Leaf Sports & Owner(s) Entertainment Ltd. (Larry Tanenbaum, chairman) General manager Brian Burke Head coach Ron Wilson Captain Dion Phaneuf Minor league Toronto Marlies (AHL) affiliates Reading Royals (ECHL) 13 (1917±18, 1921±22, 1931±32, 1941±42, 1944±45, 1946±47, 1947± Stanley Cups 48, 1948±49, 1950±51, 1961±62, 1962±63, 1963±64, 1966±67) Conference 0 championships Presidents' Trophy 0 Division 5 (1932±33, 1933±34, 1934±35, championships 1937±38, 1999±00) The Toronto Maple Leafs are a professional ice hockey team based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. They are members of the Northeast Division of the Eastern Conference of the National Hockey League (NHL). The organization, one of the "Original Six" members of the NHL, is officially known as the Toronto Maple Leaf Hockey Club and is the leading subsidiary of Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment (MLSE). They have played at the Air Canada Centre (ACC) since 1999, after 68 years at Maple Leaf Gardens. Toronto won their last Stanley Cup in 1967. The Leafs are well known for their long and bitter rivalries with the Montreal Canadiens and the Ottawa Senators. -

Norman and Thelma Meade

Call to reserve your Gluten Dine-in Special Free choices now (204) 467-2236 available Hwy 67, 162 - 2nd Ave. N. Lunch (Tues-Sat) 11 am -12 noon Made Stonewall, MB with the fre ts Dinner (Mon-Sat) 4-5 pm (Call to reserve) shest ingredien www.pizzaden.ca Mobile Foot Care Nurses FREE COPY 204-837-6629 •BlueCross&DVAProviders •Specializei •GiftCertsAvailable,Visa/MCnDiabetics .com V11-N11 Apr 2 - Apr 24/13 Read Senior Scope online at www.seniorscope.com 204-467-9000 - Advertising • Story Ideas • Comments Caregivers Are Celebrated Many gathered at the Manitoba Hydro building downtown Winnipeg, April 2, 2013, to celebrate the 2nd Annual Caregiver Recognition Day in Manitoba and raise awareness about the irreplaceable contributions of unpaid caregivers. CareAware Manitoba, a new, innovative initiative developed to raise awareness of Manitobans seniorscope who provide unpaid care and support to family members and friends through education, information and inspiration, was also launched. Minister Rondeau brought greetings and words on behalf of the Province of Manitoba and then the President of the Caregiver’s Council Bob Thompson Photo by Deborah Lorteau also spoke on the importance of the Julie Donaldson (left) of Home Instead Senior Care work that they do. www. and Syva-Lee Wildenmann of Rupert's Land Caregiver Services. Continued on page 2 Spotlight: Norm & Thelma Meade Seniors Lifestyles... By Scott Taylor By Michael van Lierop PG 5 “The world is a little short of Travel to Cuba- love, but PART III (The Final Chapter) we’ve By Rick Goodman and Beatrice Daigneault always tried PG 10 204-467-9000 www.seniorscope.com [email protected] to take our love into the What’s the real reward world.” for Quitting Smoking? Ask Roger Currie - Managing Thelma and Norman Meade PG 2 Your Own Health Care PG 11 Inside this issue.. -

Press Clips September 25, 2013 Sabres Stay Patient While Rebuilding Through Youth by John Wawrow Associated Press September 24, 2013

Buffalo Sabres Daily Press Clips September 25, 2013 Sabres stay patient while rebuilding through youth By John Wawrow Associated Press September 24, 2013 BUFFALO, N.Y. — Sabres coach Ron Rolston is reminded of the changes taking place in downtown Buffalo every day he heads into work. There's a construction site across the street from the team's arena, where Sabres owner Terry Pegula's HarborCenter hotel and entertainment complex is being erected. Then there's the major overhaul the Sabres themselves have been undergoing over the past eight months. They're both works in progress, and also reflect the potential of a brighter future in Buffalo. "I would say it's a good correlation and analogy," Rolston said. "It's both out front and in the arena." Rolston is part of the Sabres' transformation in replacing longtime coach Lindy Ruff, who was fired in February. The changes didn't end there during what became a tumultuous, lockout-shortened season that ended with Buffalo missing the playoffs for the fourth time in six years. Before the season was over, the Sabres purged much of their old guard — including captain Jason Pominville — as part of a youth movement to shake up what had been an aging, high-priced and under-achieving core. And more changes could still be store, with goalie Ryan Miller and forward Thomas Vanek's futures uncertain beyond this season. Both are entering the final years of their contracts, and the Sabres haven't ruled out trading one or both. That's left Rolston tempering his early expectations of an opening-day roster that could feature as many as seven rookies, including 18-year-old defenseman Rasmus Ristolainen. -

'Friendly City' Also Known As 'Dangerous'

Page 8 · The Pioneer · January 26, 2012 On the street We asked people on the street the following question: What is your opinion of Tim Hortons new coffee cup sizes? Phillip Fife, self- Sherry Wood, self- Avita Baskin, retiree, Dennis Baskin, Bob Dolan, marina Ferdinand Golva, employed contractor, employed, “I think “I think Tim Hortons is retiree, “I think it’s up owner, “I don’t have retiree, “I think it’s a “We don’t need that the size changes a well run operation to the company to do an opinion, because good thing – you get to compete with are confusing. I think – I wish I had some of whatever they want I’ve never seen one, more for the same Starbucks or Second for the first couple their business sense!” to do. If they want and I probably won’t money. Really, I think Cup. If you want a of months, everyone to raise the price or ever have one – it’s you’re saving. They bigger size, make a won’t know what increase the size, it’s too much! You don’t have to change to bigger size; don’t just they’re ordering.” up to them. And I’ll need 24 ounces of stay competitive.” change the name and decide if I want to buy coffee. We drink too Editorial put the price up.” from them!” much of that stuff.” ‘Friendly city’ also known as ‘dangerous’ After the gold rush, Belleville was known as the Gateway to the Golden North. After a Belleville Intelligencer contest, launched in 1914, the slogan for our city became “A Bigger and Better Belleville.” In 1923, the chamber of commerce started an official search for a slogan.