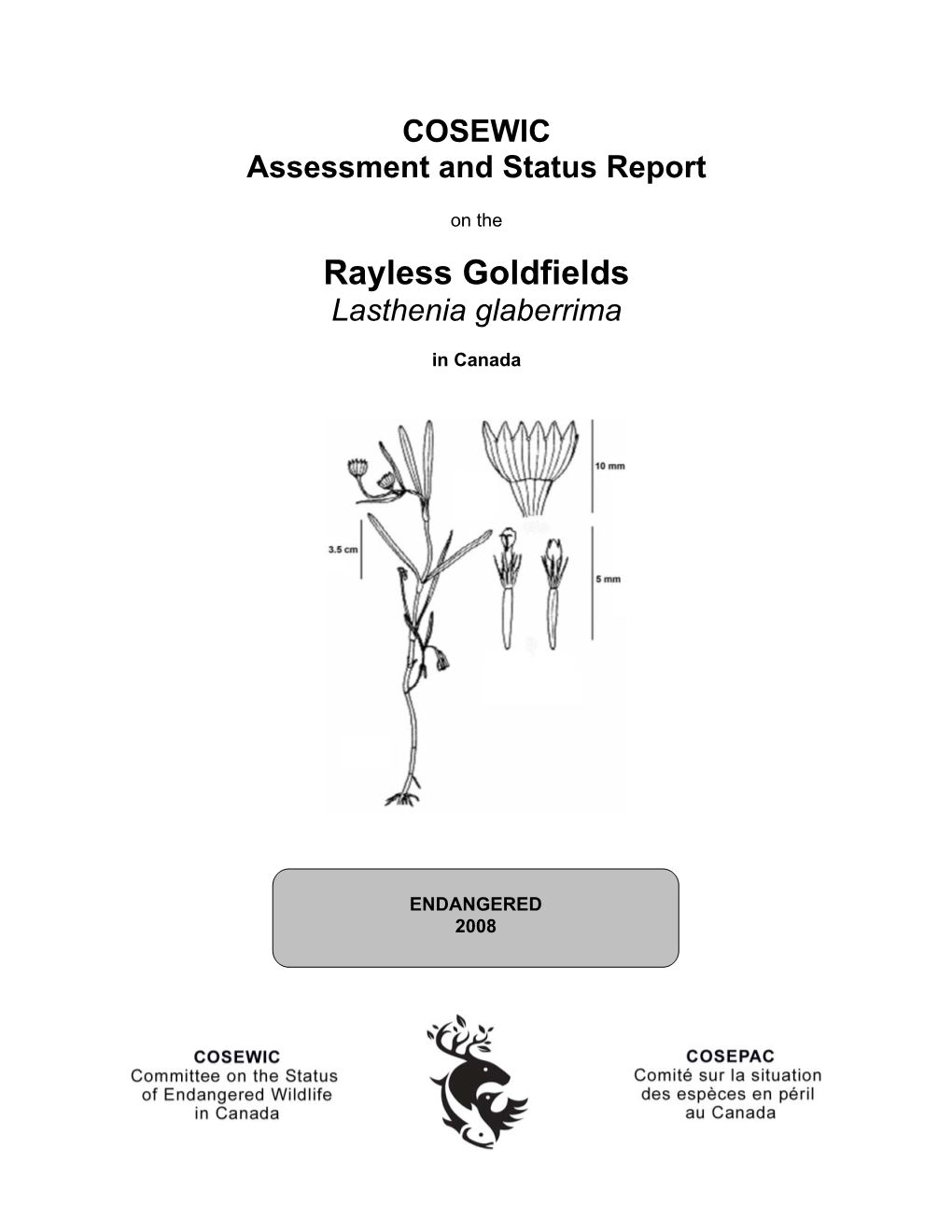

Rayless Goldfields (Lasthenia Glaberrima) Is a Member of the Aster Family (Asteraceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coreopsideae Daniel J

Chapter42 Coreopsideae Daniel J. Crawford, Mes! n Tadesse, Mark E. Mort, "ebecca T. Kimball and Christopher P. "andle HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND PHYLOGENY In a cladistic analysis of morphological features of Heliantheae by Karis (1993), Coreopsidinae were reported Morphological data to be an ingroup within Heliantheae s.l. The group was A synthesis and analysis of the systematic information on represented in the analysis by Isostigma, Chrysanthellum, tribe Heliantheae was provided by Stuessy (1977a) with Cosmos, and Coreopsis. In a subsequent paper (Karis and indications of “three main evolutionary lines” within "yding 1994), the treatment of Coreopsidinae was the the tribe. He recognized ! fteen subtribes and, of these, same as the one provided above except for the follow- Coreopsidinae along with Fitchiinae, are considered ing: Diodontium, which was placed in synonymy with as constituting the third and smallest natural grouping Glossocardia by "obinson (1981), was reinstated following within the tribe. Coreopsidinae, including 31 genera, the work of Veldkamp and Kre# er (1991), who also rele- were divided into seven informal groups. Turner and gated Glossogyne and Guerreroia as synonyms of Glossocardia, Powell (1977), in the same work, proposed the new tribe but raised Glossogyne sect. Trionicinia to generic rank; Coreopsideae Turner & Powell but did not describe it. Eryngiophyllum was placed as a synonym of Chrysanthellum Their basis for the new tribe appears to be ! nding a suit- following the work of Turner (1988); Fitchia, which was able place for subtribe Jaumeinae. They suggested that the placed in Fitchiinae by "obinson (1981), was returned previously recognized genera of Jaumeinae ( Jaumea and to Coreopsidinae; Guardiola was left as an unassigned Venegasia) could be related to Coreopsidinae or to some Heliantheae; Guizotia and Staurochlamys were placed in members of Senecioneae. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Mcgrath State Beach Plants 2/14/2005 7:53 PM Vascular Plants of Mcgrath State Beach, Ventura County, California by David L

Vascular Plants of McGrath State Beach, Ventura County, California By David L. Magney Scientific Name Common Name Habit Family Abronia maritima Red Sand-verbena PH Nyctaginaceae Abronia umbellata Beach Sand-verbena PH Nyctaginaceae Allenrolfea occidentalis Iodinebush S Chenopodiaceae Amaranthus albus * Prostrate Pigweed AH Amaranthaceae Amblyopappus pusillus Dwarf Coastweed PH Asteraceae Ambrosia chamissonis Beach-bur S Asteraceae Ambrosia psilostachya Western Ragweed PH Asteraceae Amsinckia spectabilis var. spectabilis Seaside Fiddleneck AH Boraginaceae Anagallis arvensis * Scarlet Pimpernel AH Primulaceae Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa PH Saururaceae Apium graveolens * Wild Celery PH Apiaceae Artemisia biennis Biennial Wormwood BH Asteraceae Artemisia californica California Sagebrush S Asteraceae Artemisia douglasiana Douglas' Sagewort PH Asteraceae Artemisia dracunculus Wormwood PH Asteraceae Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata Big Sagebrush S Asteraceae Arundo donax * Giant Reed PG Poaceae Aster subulatus var. ligulatus Annual Water Aster AH Asteraceae Astragalus pycnostachyus ssp. lanosissimus Ventura Marsh Milkvetch PH Fabaceae Atriplex californica California Saltbush PH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex lentiformis ssp. breweri Big Saltbush S Chenopodiaceae Atriplex patula ssp. hastata Arrowleaf Saltbush AH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex patula Spear Saltbush AH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex semibaccata Australian Saltbush PH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex triangularis Spearscale AH Chenopodiaceae Avena barbata * Slender Oat AG Poaceae Avena fatua * Wild -

Literature Cited

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 19, 20, and 21, whether as selected references, in text, or in nomenclatural contexts. In citations of articles, both here and in the taxonomic treatments, and also in nomenclatural citations, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbre- viated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. In nomenclatural citations (only), book titles are rendered in the abbreviated forms recommended in F. A. Stafleu and R. S. Cowan (1976–1988) and F. A. Stafleu and E. A. Mennega (1992+). Here, those abbreviated forms are indicated parenthetically following the full citations of the corresponding works, and cross references to the full citations are interpolated in the list alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix “a”; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with “b”. Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. -

Tidal Marsh Recovery Plan Habitat Creation Or Enhancement Project Within 5 Miles of OAK

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California California clapper rail Suaeda californica Cirsium hydrophilum Chloropyron molle Salt marsh harvest mouse (Rallus longirostris (California sea-blite) var. hydrophilum ssp. molle (Reithrodontomys obsoletus) (Suisun thistle) (soft bird’s-beak) raviventris) Volume II Appendices Tidal marsh at China Camp State Park. VII. APPENDICES Appendix A Species referred to in this recovery plan……………....…………………….3 Appendix B Recovery Priority Ranking System for Endangered and Threatened Species..........................................................................................................11 Appendix C Species of Concern or Regional Conservation Significance in Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California….......................................13 Appendix D Agencies, organizations, and websites involved with tidal marsh Recovery.................................................................................................... 189 Appendix E Environmental contaminants in San Francisco Bay...................................193 Appendix F Population Persistence Modeling for Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California with Intial Application to California clapper rail …............................................................................209 Appendix G Glossary……………......................................................................………229 Appendix H Summary of Major Public Comments and Service -

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore EIR BIOLOGICAL TECHNICAL REPORT PROPOSED CARMAX AUTO SUPERSTORE PROJECT CITY OF OCEANSIDE, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: EnviroApplications, Inc. 2831 Camino del Rio South, Suite 214 San Diego, California 92108 Contact: Megan Hill 619-291-3636 Prepared by: 4629 Cass Street, #192 San Diego, California 92109 Contact: Melissa Busby 858-334-9507 September 29, 2020 Revised March 23, 2021 Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 6 1.1 Proposed Project Location .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Proposed Project Description ............................................................................... 6 SECTION 2.0 – METHODS AND SURVEY LIMITATIONS ............................................ 8 2.1 Background Research .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 General Biological Resources Survey .................................................................. 8 2.3 Jurisdictional Delineation ...................................................................................... 9 2.3.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jurisdiction .................................................... 9 2.3.2 Regional Water Quality -

An Investigation of the Reproductive Ecology and Seed Bank

California Department of Fish & Game U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Endangered Species Act (Section-6) Grant-in-Aid Program FINAL PROJECT REPORT E-2-P-35 An Investigation of the Reproductive Ecology and Seed Bank Dynamics of Burke’s Goldfields (Lasthenia burkei), Sonoma Sunshine (Blennosperma bakeri), and Sebastopol Meadowfoam (Limnanthes vinculans) in Natural and Constructed Vernal Pools Christina M. Sloop1, 2, Kandis Gilmore1, Hattie Brown3, Nathan E. Rank1 1Department of Biology, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, CA 2San Francisco Bay Joint Venture, Fairfax, CA 3Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation, Santa Rosa, CA Prepared for Cherilyn Burton ([email protected]) California Department of Fish and Game, Habitat Conservation Division 1416 Ninth Street, Room 1280, Sacramento, CA 95814 March 1, 2012 1 1. Location of work: Santa Rosa Plain, Sonoma County, California 2. Background: Burke’s goldfield (Lasthenia burkei), a small, slender annual herb in the sunflower family (Asteraceae), is known only from southern portions of Lake and Mendocino counties and from northeastern Sonoma County. Historically, 39 populations were known from the Santa Rosa Plain, two sites in Lake County, and one site in Mendocino County. The occurrence in Mendocino County is most likely extirpated. From north to south on the Santa Rosa Plain, the species ranges from north of the community of Windsor to east of the city of Sebastopol. The long-term viability of many populations of Burke’s goldfields is particularly problematic due to population decline. There are currently 20 known extant populations, a subset of which were inoculated into pools at constructed sites to mitigate the loss of natural populations in the context of development. -

Recovery Plan for the Santa Rosa Plain

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for the Santa Rosa Plain Blennosperma bakeri (Sonoma sunshine) Lasthenia burkei (Burke’s goldfields) Limnanthes vinculans (Sebastopol meadowfoam) California tiger salamander Sonoma County Distinct Population Segment (Ambystoma californiense) Lasthenia burkei Blennosperma bakeri Limnanthes vinculans Jo-Ann Ordano J. E. (Jed) and Bonnie McClellan Jo-Ann Ordano © 2004 California Academy of Sciences © 1999 California Academy of Sciences © 2005 California Academy of Sciences Sonoma County California Tiger Salamander Gerald Corsi and Buff Corsi © 1999 California Academy of Sciences Disclaimer Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, Tribal agencies, and other affected and interested parties. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Costs indicated for action implementation and time of recovery are estimates and subject to change. Recovery plans do not obligate other parties to undertake specific actions, and may not represent the views or the official positions of any individuals or agencies involved in recovery plan formulation, other than the Service. Recovery plans represent our official position only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. LITERATURE CITATION SHOULD READ AS FOLLOWS: U.S. -

Biology Report

MEMORANDUM Scott Batiuk To: Lynford Edwards, GGBHTD From: Plant and Wetland Biologist [email protected] Date: June 13, 2019 Verification of biological conditions associated with the Corte Madera 4-Acre Tidal Subject: Marsh Restoration Project Site, Professional Service Agreement PSA No. 2014- FT-13 On June 5, 2019, a WRA, Inc. (WRA) biologist visited the Corte Madera 4-Acre Tidal Marsh Restoration Project Site (Project Site) to verify the biological conditions documented by WRA in a Biological Resources Inventory (BRI) report dated 2015. WRA also completed a literature review to confirm that special-status plant and wildlife species evaluations completed in 2015 remain valid. Resources reviewed include the California Natural Diversity Database (California Department of Fish and Wildlife 20191), the California Native Plant Society’s Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (California Native Plant Society 20192), and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Information for Planning and Consultation database (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 20193). Biological Communities In general, site conditions are similar to those documented in 2015. The Project Site is a generally flat site situated on Bay fill soil. A maintained berm is present along the western and northern boundaries. Vegetation within the Project Site is comprised of dense, non-native species, characterized primarily by non-native grassland dominated by Harding grass (Phalaris aquatica) and pampas grass (Cortaderia spp.). Dense stands of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) are present in the northern and western portions on the Project Site. A small number of seasonal wetland depressions dominated by curly dock (Rumex crispus), fat hen (Atriplex prostrata) and brass buttons (Cotula coronopifolia) are present in the northern and western portions of the Project Site, and the locations and extent of wetlands observed are similar to what was documented in 2015. -

Vernal Pool Landscape As Illustrated in the Butte Area Natural Resources Conservation Service Soil Survey ANDREW E

CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Plants .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Science and Vernal Pool Conservation: Research Questions, Methodologies and Applications Based on a Case Study of Pogogyne abramsii in San Diego County, California ELLEN T. BAUDER ..................................................................................................................... 5 The Population and Genetic Status of the Endangered Vernal Pool Annual Limnanthes floccosa Howell ssp. californica Arroyo: Implications for Species Recovery CHRISTINA M. SLOOP .............................................................................................................. 25 The Ecology, Evolution, and Diversification of the Vernal Pool Niche in Lasthenia (Madieae, Asteraceae) NANCY C. EMERY, LORENA TORRES-MARTINEZ, ELISABETH FORRESTEL, BRUCE G. BALDWIN AND DAVID D. ACKERLY......................................................................................... 39 A Comparison of Pollination Interactions in Natural and Created Vernal Pools in the Santa Rosa Plain, Sonoma County, California JOAN M. LEONG....................................................................................................................... 59 Animals ........................................................................................................................................... -

Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B. Harper Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Sula Vanderplank Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Mark Dodero Recon Environmental Inc., San Diego, California Sergio Mata Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Jorge Ochoa Long Beach City College, Long Beach, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Alan B.; Vanderplank, Sula; Dodero, Mark; Mata, Sergio; and Ochoa, Jorge (2011) "Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol29/iss1/4 Aliso, 29(1), pp. 25–42 ’ 2011, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PLANTS OF THE COLONET REGION, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, AND A VEGETATION MAPOF COLONET MESA ALAN B. HARPER,1 SULA VANDERPLANK,2 MARK DODERO,3 SERGIO MATA,1 AND JORGE OCHOA4 1Terra Peninsular, A.C., PMB 189003, Suite 88, Coronado, California 92178, USA ([email protected]); 2Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711, USA; 3Recon Environmental Inc., 1927 Fifth Avenue, San Diego, California 92101, USA; 4Long Beach City College, 1305 East Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, California 90806, USA ABSTRACT The Colonet region is located at the southern end of the California Floristic Province, in an area known to have the highest plant diversity in Baja California.