Landscapes of Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

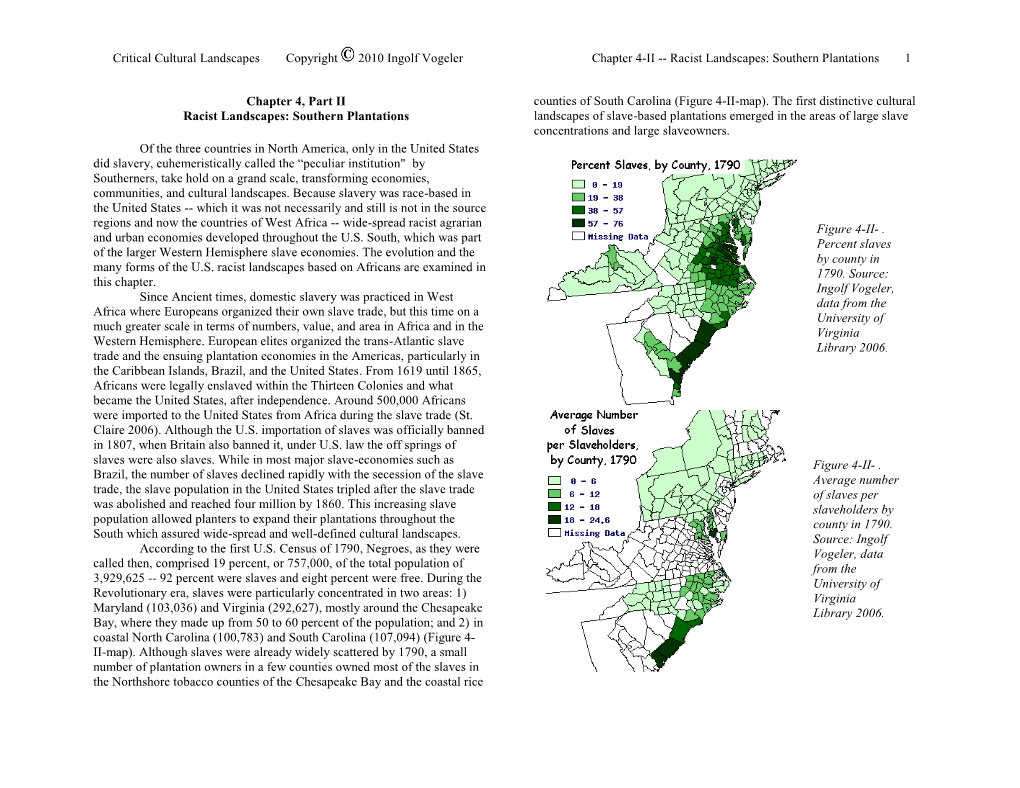

Recommended publications

-

36 Hours in Charleston

36 Hours in Charleston Charleston is a popular destination for travelers; if your time in Charleston is limited these are the top locations to visit during your stay. Day 1 Magnolia Plantation and Gardens: Travel + Leisure Magazine rated Magnolia Plantation and Gardens as one of “America’s Most Beautiful Gardens.” Founded in 1676 by the Drayton family it is also America’s oldest public garden with opening its doors to visitors in 1870. The property is based on the romantic garden movement where the gardens are full, lush, and sometimes overgrown. (Tickets start at $20.00pp) www.magnoliaplantation.com Middleton Place: Where Magnolia is romantic Middleton Place is structured and largely landscaped and sculpted in fact its home to the oldest landscaped gardens in America. Its early days were tragic as it was burned just months before the ending of the Civil War and an earthquake in 1886 destroyed much of the main residence. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that the property could be restored. This is the only plantation with a full service restaurant serving lunch and dinner. (Tickets start at $29.00pp) www.middletonplace.org Mepkin Abbey: A little known gem is the Mepkin Abbey. It is home for Trappist Monks (think Trappist Preserves) who live according to the Rule of St. Benedict. The grounds and gardens are open for public viewing, but check their website before attending as there are visitor guidelines. Besure to visit the Abbey Store where you can find their popular dried and powdered oyster and shitake mushrooms. (Tours start at $5.00 pp) www.mepkinabbey.org Boone Hall Plantation and Gardens: If you still have the energy head over to Boone Hall Plantation and Gardens. -

Middltrto}I Plactr a National Lfisturic Landrnark

GnnonNs, Housn a PrnNreuoN STaBLEvARDS MIDDLtrTO}I PLACtr A National lfisturic Landrnark CHenrESToN, Sourn CenolrNA iddleton Place is one of South Carolina's most enduring icons - a proud survivor of the American Revolution, Civil War, changing fortunes and natural disasters. First granted in 7675, only five years after the first English colonists arrived in the Carolinas, this National Historic Landmark has history, drama, beauty and educational discoveries for everyone in the family. For over two and ahalf centuries, these graciously landscaped gardens have Azalea Hillside enchanted visitors from all over the world. Guests stroll through vast garden "rooms," laid out with precise symmetry and balance, to the climactic view over the Butterfly Lakes and the winding Ashley River beyond. Today, as they did then, the gardens represent the Low Country's most The Refection Pool spectacular and articulate expression of an 1Sth-century ideal - the triumphant maffrage between man and nature. Walk the same footpaths through these gardens as did pre- Revolutionary statesmen. Enjoy the same vistas that inspired four generations of the distinguished Middleton family from 1747 to 1865. Here lived The Wood Nymph, c. 1810 Henry Middleton, a President of the First Continental Congress; Arthur Middleton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence; Henry Middleton, Governor of South Carolina and later Minister to Russia; and Williams Middleton, a signer of the Ordinance of Secession. DSCAPED GAN Tour the Middleton Enjoy dining at the Middleton Place Place House (77 55),bui1t Restaurantwhere an authentic Low as a gentlemar{s guest wing Country lunch is served daily and dinner beside the family residence. -

Agriculture and the Future of Food: the Role of Botanic Gardens Introduction by Ari Novy, Executive Director, U.S

Agriculture and the Future of Food: The Role of Botanic Gardens Introduction by Ari Novy, Executive Director, U.S. Botanic Garden Ellen Bergfeld, CEO, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America The more than 320 million Americans alive today depend on plants for our food, clothing, shelter, medicine, and other critical resources. Plants are vital in today’s world just as they were in the lives of the founders of this great nation. Modern agriculture is the cornerstone of human survival and has played extremely important roles in economics, power dynamics, land use, and cultures worldwide. Interpreting the story of agriculture and showcasing its techniques and the crops upon which human life is sustained are critical aspects of teaching people about the usefulness of plants to the wellbeing of humankind. Botanical gardens are ideally situated to bring the fascinating story of American agriculture to the public — a critical need given the lack of exposure to agricultural environments for most Americans today and the great challenges that lie ahead in successfully feeding our growing populations. Based on a meeting of the nation’s leading agricultural and botanical educators organized by the U.S. Botanic Garden, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America, this document lays out a series of educational narratives that could be utilized by the U.S. Botanic Garden, and other institutions, to connect plants and people through presentation -

Urban Agriculture: Long-Term Strategy Or Impossible Dream? Lessons from Prospect Farm in Brooklyn, New York

public health 129 (2015) 336e341 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Public Health journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/puhe Original Research Urban agriculture: long-term strategy or impossible dream? Lessons from Prospect Farm in Brooklyn, New York * T. Angotti a,b, a Urban Affairs & Planning at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, USA b Prospect Farm in Brooklyn, New York, USA article info abstract Article history: Proponents of urban agriculture have identified its potential to improve health and the Available online 25 February 2015 environment but in New York City and other densely developed and populated urban areas, it faces huge challenges because of the shortage of space, cost of land, and the lack Keywords: of contemporary local food production. However, large portions of the city and metro- Urban agriculture politan region do have open land and a history of agricultural production in the not-too- Land use policy distant past. Local food movements and concerns about food security have sparked a Community development growing interest in urban farming. Policies in other sectors to address diet-related ill- Food safety nesses, environmental quality and climate change may also provide opportunities to Climate change expand urban farming. Nevertheless, for any major advances in urban agriculture, sig- nificant changes in local and regional land use policies are needed. These do not appear to be forthcoming any time soon unless food movements amplify their voices in local and national food policy. Based on his experiences as founder of a small farm in Brooklyn, New York and his engagement with local food movements, the author analyzes obstacles and opportunities for expanding urban agriculture in New York. -

Sharecropping in the US South.∗

Turnover or Cash? Sharecropping in the US South.∗ Guilherme de Oliveira University of Amsterdam February 4, 2017 Abstract Between 1880 and 1940, US post offices alleviated the isolation of the Southern countryside by posting information about jobs in the growing industrial sector. Hence, post offices enhanced the outside options of employees in a time employers in the farm- ing sector used sharecropping - a contract where employers paid employees with a share of the harvested crop - to avoid labor turnover costs. This paper finds that a new post office in a county decreased sharecropping, which is evidence that sharecropping mostly resulted from the lack of outside options for employees. This is an innovative result in the share contract literature, usually more concerned about sector-level reasons such as labor turnover than about outside options. Furthermore, new light is shed on the current use of sharecropping and other share contracts such as franchising. Since share- cropping and franchising are a form of entrepreneurship, this paper suggests a reason for the negative relation between GDP per capita and entrepreneurship. Keywords: Share Contracts; Turnover; Outside Option. JEL classification: J41; J43; N30; N50. ∗I would like to thank Giuseppe Dari-Mattiacci and Carmine Guerriero for their invaluable contribution as my supervisors. I am especially grateful for the thorough comments by Torsten Jochem and Mehmet Kutluay, and to the input given by the participants at 2016 Conference of the European Law & Economics Association, 2016 Congress of the European Economic Association, 2016 Conference of the Spanish Law & Economics Association, 2016 Conference on Empirical Legal Studies in Europe, the 2015 Ronald Coase Institute Workshop - Tel Aviv, the brownbag seminar of the Finance Group at the University of Amsterdam, and at the Tinbergen Institute PhD seminar. -

Land Tenure Insecurity Constrains Cropping System Investment in the Jordan Valley of the West Bank

sustainability Article Land Tenure Insecurity Constrains Cropping System Investment in the Jordan Valley of the West Bank Mark E. Caulfield 1,2,* , James Hammond 2 , Steven J. Fonte 1 and Mark van Wijk 2 1 Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1170, USA; [email protected] 2 International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Livestock Systems and the Environment, Nairobi 00100, Kenya; [email protected] (J.H.); [email protected] (M.v.W.) * Correspondence: markcaulfi[email protected]; Tel.: +212-(0)-6-39-59-89-18 Received: 17 July 2020; Accepted: 8 August 2020; Published: 13 August 2020 Abstract: The annual income of small-scale farmers in the Jordan Valley, West Bank, Palestine remains persistently low compared to other sectors. The objective of this study was therefore to explore some of the main barriers to reducing poverty and increasing farm income in the region. A “Rural Household Multi-Indicator Survey” (RHoMIS) was conducted with 248 farmers in the three governorates of the Jordan Valley. The results of the survey were verified in a series of stakeholder interviews and participatory workshops where farmers and stakeholders provided detailed insight with regard to the relationships between land tenure status, farm management, and poverty. The analyses of the data revealed that differences in cropping system were significantly associated with land tenure status, such that rented land displayed a greater proportion of open field cropping, while owned land and sharecropping tenure status displayed greater proportions of production systems that require greater initial investment (i.e., perennial and greenhouse). -

Slavery, Sharecropping, and Sexual Inequality

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Sociology Faculty Publications Department of Anthropology and Sociology Summer 1989 Slavery, Sharecropping, and Sexual Inequality Susan A. Mann University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/soc_facpubs Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Mann, Susan A. 1989. "Slavery, Sharecropping, and Sexual Inequality." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture & Society 14, no. 4: 774-798. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slavery, Sharecropping, and Sexual Inequality Author(s): Susan A. Mann Source: Signs, Vol. 14, No. 4, Common Grounds and Crossroads: Race, Ethnicity, and Class in Women's Lives (Summer, 1989), pp. 774-798 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174684 . Accessed: 12/04/2011 15:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. -

Sharecropping in Alabama During Reconstruction: an Answer to a Problem and a Problem in the Making? (Suggested Grade Level: 10Th Grade Advanced U.S

Title of Lesson: Sharecropping in Alabama during Reconstruction: An Answer to a Problem and a Problem in the Making? (Suggested grade level: 10th Grade Advanced U.S. History to 1877) This lesson was created as a part of the Alabama History Education Initiative, funded by a generous grant from the Malone Family Foundation in 2009. Author Information: Mary Hubbard, Advanced Placement History Teacher, Retired Alabama History Education Initiative Consultant Background Information: The following links offer background information on Alabama sharecroppers during Reconstruction: • Encyclopedia of Alabama offers an extensive selection of articles and multimedia resources dealing with almost all aspects of Alabama history, geography, culture, and natural environment. Typing the word “sharecropping” into the search window yields 18 results, a mix of articles and some very powerful photographs of Alabama sharecroppers that were taken in the 1930s. The first article gives a solid overview of the history of sharecropping/tenant farming and contains links to the other resources. It includes this relevant statement: “It has been estimated that as late as early 1940s, the average sharecropper family’s income was less than 65 cents a day.” • PBS: The American Experience offers a wealth of resources for teachers. The material related to sharecropping was developed in conjunction with the American Experience series entitled “Reconstruction: The Second Civil War.” Overview of lesson: This lesson is designed to introduce the Reconstruction Period and generate greater student interest in learning about how it both succeeded and failed as a response to conditions in the South at the end of the Civil War. It focuses on the sharecropping/tenant system which developed right after the war ended, and persisted in Alabama well into the 1940s. -

The Difficult Plantation Past: Operational and Leadership Mechanisms and Their Impact on Racialized Narratives at Tourist Plantations

THE DIFFICULT PLANTATION PAST: OPERATIONAL AND LEADERSHIP MECHANISMS AND THEIR IMPACT ON RACIALIZED NARRATIVES AT TOURIST PLANTATIONS by Jennifer Allison Harris A Dissertation SubmitteD in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public History Middle Tennessee State University May 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kathryn Sikes, Chair Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle Dr. C. Brendan Martin Dr. Carroll Van West To F. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot begin to express my thanks to my dissertation committee chairperson, Dr. Kathryn Sikes. Without her encouragement and advice this project would not have been possible. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my dissertation committee members Drs. Mary Hoffschwelle, Carroll Van West, and Brendan Martin. My very deepest gratitude extends to Dr. Martin and the Public History Program for graciously and generously funding my research site visits. I’m deeply indebted to the National Science Foundation project research team, Drs. Derek H. Alderman, Perry L. Carter, Stephen P. Hanna, David Butler, and Amy E. Potter. However, I owe special thanks to Dr. Butler who introduced me to the project data and offered ongoing mentorship through my research and writing process. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Douglass for her continued professional sponsorship and friendship. The completion of my dissertation would not have been possible without the loving support and nurturing of Frederick Kristopher Koehn, whose patience cannot be underestimated. I must also thank my MTSU colleagues Drs. Bob Beatty and Ginna Foster Cannon for their supportive insights. My friend Dr. Jody Hankins was also incredibly helpful and reassuring throughout the last five years, and I owe additional gratitude to the “Low Brow CrowD,” for stress relief and weekend distractions. -

Cultivating Farmworker Injustice: the Resurgence of Sharecropping

Cultivating Farmworker Injustice: The Resurgence of Sharecropping JENNIFER T. MANION* Certain industries in the United States have always relied upon inexpensive, undemanding, and plentiful immigrant workforces. This reliance on outside labor is most notable in the agricultural industry. Indeed, from the southern plantationsfueled by slave labor to the strawberry fields on the West Coast tended by Japanesefarmers, much of the agriculturalwork in this country has been performed by newly--and involuntarily-arrivedpopulations who lack the freedom or ability to seek other means ofsupport. With immigrationfrom other countries, Mexico in particular,on the rise, it is no surprise that many Hispanic immigrants arefinding work in the agriculturalindustry. What is surprisingis that despite the enactment of laws gearedtoward protectingthese workers, they arefinding themselves little better off than their predecessors. The dijffculties that immigrant farmworkers continue to face are due in part to employers' efforts to evade the requirements of protective legislation by labeling their farmworkers as independentcontractors in sharecroppingcontracts. I. INTRODUCTION Lured by the possibility of achieving the independence that they had sought, the Ramirez family of Salinas, California, entered a contract with a local vegetable broker, Veg-a-Mix, that seemed to offer the family a chance to finally "own[ ] [their] own farm and earn[ ] a living from it."' Under the contract, the Ramirez family received a loan from Veg-a-Mix to grow zucchini and in return promised to sell their crops exclusively through the broker.2 After working under these contracts for several years, however, the Ramirez family has nothing to3 show for their hard work except a debt to Veg-a-Mix for approximately $65,000. -

Does Land Tenure Systems Affect Sustainable Agricultural

sustainability Article Does Land Tenure Systems Affect Sustainable Agricultural Development? Nida Akram 1 , Muhammad Waqar Akram 1, Hongshu Wang 1,* and Ayesha Mehmood 2 1 College of Economics and Management, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China 2 Institute of knowledge and leadership, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Punjab 54000, Pakistan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-159-4600-2021 Received: 5 July 2019; Accepted: 17 July 2019; Published: 18 July 2019 Abstract: The current study aims to investigate the agricultural investment differences among three kinds of land lease agreements and their effect on farmers’ decisions regarding sustainable growth in terms of soil conservation and wheat productivity, using cross-sectional data from rural households in Punjab, Pakistan. The “multivariate Tobit model” was used for the empirical analysis because it considers the possible substitution of investment choices and the tenancy status’ endogeneity. Compared to agricultural lands on lease contracts, landowners involved in agribusiness are more likely to invest in measures to improve soil and increase productivity. Moreover, the present study has also identified that the yield per hectare is much higher for landowners than sharecroppers, and thus, the Marshall’s assumption of low efficiency of tenants under sharecroppers is supported. Keywords: land tenure; soil conservation; Investment decision; farm productivity; land use sustainability; agricultural development 1. Introduction The reformation of agricultural land has garnered broad support in many countries. Such reformation depends to a certain extent on the assumption that agrarian land under secured land tenancy status is preferable to other types of land right arrangements [1,2]. Secured land rights ensure permanent retention of farmland, which incentivizes and encourages farmers to invest in sustainable development for long-term benefits. -

Middleton Place National Historic Landmark

MIDDLETON PLACE NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Weddings Welcome... to Middleton Place National Historic Landmark, a carefully preserved 18th century plantation and America’s oldest formal landscaped gardens. Live oaks draped in swags of Spanish moss, the house museum built in 1755 and a beautiful landscape with sculpted terraces and blooming color, combine to provide a setting of unmatched elegance and charm. Enhanced by the French inspired formal surroundings, your wedding at Middleton Place will be enriched with warmth, elegance, and attention to every detail. The stunning outdoor venues overlooking the Ashley River and rice fields provide ideal ceremony locations. Whether you are planning an intimate, gathering or grand affair, the staff will assist you in selecting a location tailored to your specific needs. Chef Chris Lukic and his banquet team at the Middleton Place Restaurant take great pride in creating delicious menus that utilize the freshest local ingredients, staying true to Charleston’s culinary heritage. Two-time Platinum Partners in the Sustainable Seafood Initiative, the Middleton Place Chefs also enjoy preparing produce from the on-site certified organic farm. Whether you are planning a wedding weekend filled with a rehearsal dinner Oyster Roast in the plantation Stableyards, a bridal luncheon in the gardens, a family dinner in the Cypress Room, or an elegant wedding reception in the Pavilion, Middleton Place can provide a memorable plantation experience. MIDDLETON PLACE Special Group Services 4300 Ashley River Road, Charleston, SC 29414 | (843) 377-0548 | [email protected] 10 8 9 7 1 2 5 6 4 3 Venues 1 Secret Gardens Consisting of two hidden garden rooms, the larger of the two is embellished with four marble statues representing the four seasons.