Does Law Rule in Zambia?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia Nieuwsbrief

ISSN: 1380-8915 nr 116 Zambia Nieuwsbrief Kwartaalblad van de Stichting Werkgroep Zambia nr. 116 dec 2006 Beste Lezer De redactie was blij verrast met veel bijdragen van diverse kanten, inclusief INHOUD bijpassende foto’s. Vandaar dat u een superdikke Zambia Nieuwsbrief Politiek Binnenland 2 ontvangt. Verkiezingen (Thera Rasing) 6 Het belangrijkste onderwerp is ongetwijfeld de verkiezingen. Onze eigen Binnenland 7 redacteur in Nederland bespreekt de uitslag: zittend president Mwanawasa Economie 8 kreeg 43% van de stemmen, ruim meer dan Sata (29%) en Hichilema (25%); Landbouw en Voedsel 10 in het parlement is de MMD verreweg de grootste partij, die echter net geen Energie 12 absolute meerderheid heeft. Mijnbouw 13 Vanuit Zambia zelf geeft Thera Rasing op de UNZA een impressie van de verkiezingen, beschrijft een rondtrekkende Dick Jaeger zijn indruk en kijkt Gezondheidszorg 14 Een jaar Ambassadeur in Zambia 16 ambassadeur Middeldorp terug op het verkiezingsproces. Samen met de EU- waarnemers onder leiding van de Belgische diplomaat Neyts zijn zij allemaal Werkbezoek Chipata en Lundazi 18 zeer positief over hoe het nu gelopen is. De uitslag wordt dan ook niet in Natuur & Milieu 19 twijfel getrokken. De diverse bijdragen hierover geven een mooi beeld. Toerisme 20 NL ondernemer; Safari Lodge 21 Terugkijken is een gemeenschappelijke noemer in een aantal bijdragen. Dick Reisimpressie: Dick Jaeger 22 Jaeger vergelijkt het Zambia dat hij nu aantreft met zijn ervaring van 40 jaar Transport 24 geleden en de eerste Unza-docent, Pat Hiddleston, neemt ons ook 40 jaar mee terug naar de oprichting van de Unza. De ambassadeur beschouwt voor ons Onderwijs 25 zijn eerste jaar als ambassadeur en is positief over de ontwikkelingen. -

Members of the Northern Rhodesia Legislative Council and National Assembly of Zambia, 1924-2021

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA Parliament Buildings P.O Box 31299 Lusaka www.parliament.gov.zm MEMBERS OF THE NORTHERN RHODESIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA, 1924-2021 FIRST EDITION, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 3 PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 9 PART A: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1924 - 1964 ............................................... 10 PRIME MINISTERS OF THE FEDERATION OF RHODESIA .......................................................... 12 GOVERNORS OF NORTHERN RHODESIA AND PRESIDING OFFICERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) ............................................................................................... 13 SPEAKERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) - 1948 TO 1964 ................................. 16 DEPUTY SPEAKERS OF THE LEGICO 1948 TO 1964 .................................................................... -

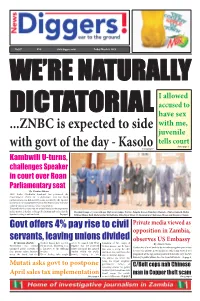

ZNBC Is Expected to Side with Govt of The

No387 K10 www.diggers.news Friday March 8, 2019 WE’RE NATURALLY I allowed accused to DICTATORIAL have sex with me, ...ZNBC is expected to side juvenile tells court Story page 3 with govt of the day - KasoloStory page 7 Kambwili U-turns, challenges Speaker in court over Roan Parliamentary seat By Zondiwe Mbewe NDC leader Chishimba Kambwili has petitioned the Constitutional Court for a declaration that his Roan parliamentary seat did not fall vacant as ruled by the Speaker of the National Assembly Dr Patrick Matibini because the latter violated various provisions of the Constitution. Kambwili who has cited the Attorney General as the respondent in this matter, is further seeking a declaration and order that the President Lungu (c) poses with new High Court judges: Evaristo Pengele, Koreen Etambuyu Mwenda - Zimba, Kenneth Mulife, Speaker’s ruling is null and void. To page 5 Wilfred Muma, Ruth Hachitapika Chibbabbuka, Abha Nayar Patel, SC, Bonaventure Chakwawa Mbewe and Kazimbe Chenda. Govt offers 4% pay rise to civil Private media viewed as opposition in Zambia, servants, leaving unions divided observes US Embassy By Mirriam Chabala workers’ unions have rejected not to be named, told News formation of two camps of By Stuart Lisulo Government has offeredthe proposal, describing it as Diggers! that the proposed workers unions - one for those Zambia has a lot of work to do in embracing divergent views unionised public servants a a disservice to the suffering salary increment has spurred that want to accept the offer because the private news media are still being viewed as a four percent salary increase workers. -

Zambia Nieuwsbrief Kwartaalblad Van De Stichting Werkgroep Zambia Nr

ISSN: 1380-8915 nr 123 Zambia Nieuwsbrief Kwartaalblad van de Stichting Werkgroep Zambia nr. 123 september 2008 In de vorige ZNB werden een aantal speciale dagen belicht, waaronder de Zambiadag van 4 juli in Den Haag, met als eregast eerste president dr. INHOUD Kenneth Kaunda. Over deze dag, waarin ambassadeur Middeldorp ook het Politiek Binnenland 2 ambassadeursstokje overdroeg aan collega Molenaar, een verslag in de Economie 5 nieuwsbrief. Tevens schreef ambassadeur Middeldorp voor de nieuwsbrief Economie bijdrage ambassade 8 een terugblik op zijn ambtsperiode. Maar deze dag wordt overschaduwd door een andere bijzondere, tragische dag, of eigenlijk twee dagen. Mijnbouw 10 Transport 11 Na het overlijden van Levy Mwanawasa Milieu & Water 12 Op 19 augustus overleed derde president, Levy Ingezonden: Gertjan van Stam 13 Mwanawasa in Parijs aan de gevolgen van een Toerisme 14 beroerte en op 3 september, de dag waarop NL initiatieven Kasanka 15 hij 60 zou zijn geworden, werd hij in Lusaka Terugblik ambasadeur 16 in Embassy Park begraven. Waarnemend Zambiadag 18 president Rupiah Banda riep op tot eensgezindheid, vredelievend en waardigheid Ingezonden: Wim Goris 19 tijdens de 21 dagen durende rouwperiode. Onderwijs 21 Het feit dat sommigen de naam van Embassy Park Gezondheidszorg 22 wilden wijzigen in Heroes Acre, wijst erop dat de overleden president groot Religie, Cultuur, Boulevard 24 aanzien genoot onder zijn landgenoten. De hele natie stond verslagen en in rouw bijeen. Bij dezen wil ook de redactie van de Zambia Nieuwsbrief Sport 26 haar deelneming betuigen. Levy Mwanawasa zal in onze herinnering Kinderen 28 voortleven als de president die democratie en economische vooruitgang Vrouwen 29 wilde bevorderen voor alle Zambianen en die de “regel van de wet” wilde Ingezonden: Muli Shani 30 vestigen, boven persoonlijke of tribale belangen.