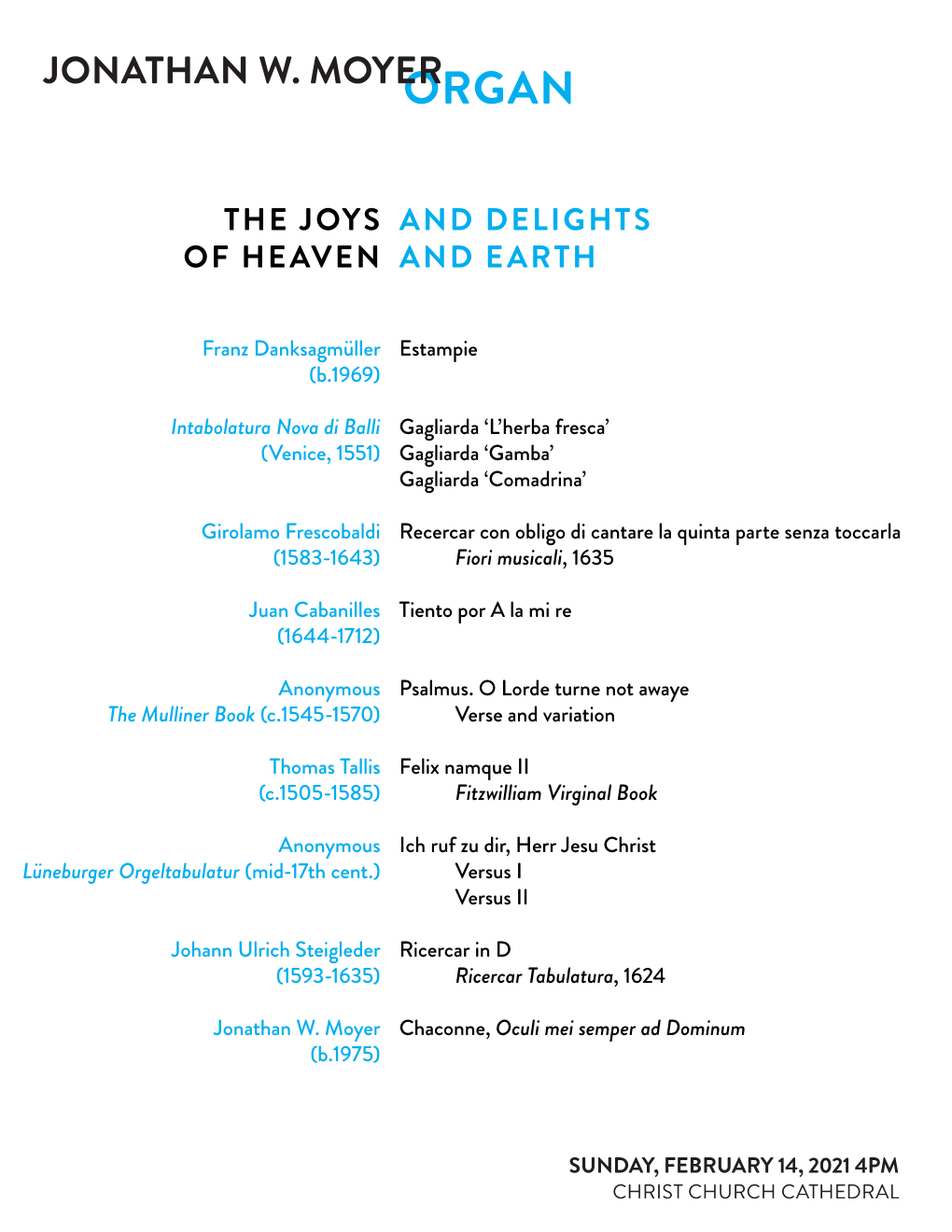

Jonathan W. Moyerorgan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Historical and Analytical Study of Renaissance Music for the Recorder and Its Influence on the Later Repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Woodhill, Vanessa, An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire, Master of Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2179 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF RENAISSANCE MUSIC FOR THE RECORDER AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LATER REPERTOIRE by VANESSA WOODHILL. B.Sc. L.T.C.L (Teachers). F.T.C.L A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong. "u»«viRsmr •*"! This thesis is submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wotlongong in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or similar institution. Copyright for the extracts of musical works contained in this thesis subsists with a variety of publishers and individuals. Further copying or publishing of this thesis may require the permission of copyright owners. Signed SUMMARY The material in this thesis approaches Renaissance music in relation to the recorder player in three ways. -

The 2007 Edition Is Available in PDF Form By

VOX The new Chapter Secretary: Nick Gale [email protected] The Academy of St Cecilia Patrons: The Most Hon. The Marquess of Londonderry Dean and Education Advisor: Sir Peter Maxwell Davies CBE John McIntosh OBE Vice Patrons: James Bowman CBE, Naji Hakim, Monica Huggett [email protected] From the master Treasurer: Paula Chandler [email protected] elcome to the 2007 edition of Vox - the mouthpiece of the Academy of St Cecilia. Registrar: Jonathan Lycett We always welcome contributions from our members - [email protected] indeed without them Vox would not exist. In this edition we announce our restructured Chapter and its new members; feature a major article on Thomas Tallis Director of Communications: whose 500th anniversay falls at this time; and we Alistair Dixon review the Academy’s most major event to date, the [email protected] chant day held in June 2006. Our new address is: Composer in Residence: Nicholas O'Neill The Academy of St Cecilia Email: [email protected] C/o Music Department [email protected] Cathedral House Westminster Bridge Road Web site: LONDON SE1 7HY www.academyofsaintcecilia.com Archivist: Graham Hawkes Tel: 020 8265 6703 [email protected] ~ Page 1 ~ ~ Page 2 ~ Advisors to the Academy Thomas Tallis (c.1505 - 1585) Alistair Dixon, a member of the Chapter of the Academy, spent ten years studying and performing the music of Thomas Tallis. In 2005 Academic Advisor: he released the last in the series of recordings with his choir, Chapelle Dr Reinhard Strohm PhD (KU Berlin) FBA HonFASC. Heather Professor of Music Oxford University du Roi, of the Complete Works of Thomas Tallis in nine volumes. -

Stainer & Bell

STAINER & BELL INFORMATION SHEET ASK 63 MUNDY, William Library Volume: Latin Antiphons and Psalms edited by Frank Ll. Harrison. Stock No. EC2 (printed to demand: comb-bound) Works by William Mundy can also be found in: Consort Songs (edited Philip Brett). Stock No. MB22 Elizabethan Consort Music I (edited Paul Doe). Stock No. MB44 The Gyffard Partbooks I (transcribed and edited by David Mateer). Stock No. EC48 The Gyffard Partbooks II (transcribed and edited by David Mateer). Stock No. EC51 The Mulliner Book (newly transcribed and edited by John Caldwell). Stock No. MB1 Except where an asterisk is shown against a title, our archive and offprint service can usually provide authorised photocopies. Prices are available on application. Individual choral titles from the Early English Church Music series are also available for purchase as Adobe Acrobat PDF files through the secure Stainer & Bell online shop. Please see www.eecm.net for full details. Title Details No. of pages Notes Adhaesit Pavimento SATBB 11 in EC2 Adolescentulus Sum Ego SAATBB 12 in EC2 Alleluya [V. Per te dei genitrix] I 4-part 1 in EC48 Alleluya [V. Per te dei genitrix] II 4-part 1 in EC48 Beati Immaculati SAATB 11 in EC2 Domine, Non Est Exaltatum SATTBB 11 in EC2 Domine, Quis Habitabit SSAATB 25 in EC2 Eructavit Cor Meum SATTBB 24 in EC2 Exurge Christe 4-part 1 in MB1 Exurge Christe (attrib.) 4-part 2 in EC48 Fantasia 5-part 4 in MB44 Fie, fie, my fate Consort song 2 in MB22 In Aeternum SAA (or T) TBB 13 in EC2 In exitu Israel [with BYRD, William 4-part 15 in EC48 and SHEPPARD, -

The Bell Spring 2011

SPRING 2011 THE BELL Although the musical archives of the world have yielded up their fair A CAMBRIDGE share of surprising ‘lost’ or forgotten early works by great MASS composers, few of these discoveries might be regarded with more wonder than the Mass of 1899 by Ralph Vaughan Williams. Submitted for the Cambridge degree of Doctor of Music shortly after his 27th birthday, and lasting around three quarters of an hour, it was by far the largest of the composer’s pieces to predate A Sea Symphony of 1909, and in any context would Photograph of Trinity College, Cambridge © Andrew Dunn be a remarkable achievement. In a sense, it was neither lost nor forgotten, merely overlooked for more than a century – though that omission is in itself remarkable, for the Mass was in Michael Kennedy’s catalogue of the composer’s work, and the score preserved in Cambridge University Library. It was there in 2007 that Alan Tongue first set eyes on it and, galvanised by the 155 pages of autograph manuscript, resolved to obtain permission from The Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust to undertake a transcription. There were no parts, for the piece had never been performed, and in places there were wrong notes, incorrect transpositions and missing dynamics that would surely have been corrected in due course by a professional copyist. Nonetheless, the composer’s intentions were entirely clear, as was the ambitious scope of the piece, which significantly extends our understanding of Vaughan Williams’ artistic development. Given the context, the title A Cambridge Mass (for SATB soloists, double chorus and orchestra) immediately suggested itself, and not just on account of Vaughan Williams receiving the university degree. -

OCTOBER, 2012 Independent Presbyterian Church Birmingham

THE DIAPASON OCTOBER, 2012 Independent Presbyterian Church Birmingham, Alabama Cover feature on pages 26–28 THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundred Third Year: No. 10, Whole No. 1235 OCTOBER, 2012 In the wind . and there are pointy-painful heat sinks Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 John Bishop’s fascinating column (Au- (fi n-shaped radiators) across the back so An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, gust 2012) on electricity and wind in they’re awful to handle. the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music pipe organs misstates what rectifi ers and Yesterday, I installed a new rectifi er transformers do. A transformer takes an in an organ in Manhattan that was small AC voltage and changes it to another AC and light enough that I carried it in a voltage, e.g., 120 VAC to 12–16 VAC. A canvas “Bean Bag” on the subway along CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] rectifi er then takes the stepped-down AC with my “city” tool kit. Obviously, there FEATURES 847/391-1045 voltage and rectifi es it to DC. It is that have been lots of changes in how “recti- DC which electrically powers the circuits fi ers” work, but whatever goes on inside, An Interview with Montserrat Torrent Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON of the organ. John has the functions of as long as they provide the power I need Queen of Iberian organ music [email protected] by Mark J. Merrill 19 transformers and rectifi ers reversed. to run an organ’s action I’m stuck with 847/391-1044 William Mitchell calling them “rectifi ers.” An American Organ Moves to Germany Contributing Editors LARRY PALMER Columbus, Ohio Mr. -

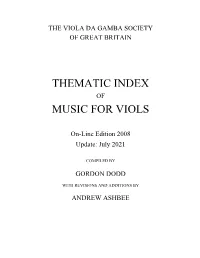

Thematic Index Music for Viols

THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN THEMATIC INDEX OF MUSIC FOR VIOLS On-Line Edition 2008 Update: July 2021 COMPILED BY GORDON DODD WITH REVISIONS AND ADDITIONS BY ANDREW ASHBEE CONTENTS Introduction 3 Acknowledgements 3 Key 6 Select Bibliography 8 Author Index for Bibliography 29 Sources (Introduction) 33 Early Editions and Facsimiles 35 Publishers and Modern Editions 51 Manuscripts in British Libraries 58 Manuscripts I Libraries outside Britain 70 Index of Composers 82 Revised and New Pages added since 2004 86 file 02 Anon (a) (staff notation) /2: two-part works A-2BC: works for treble/violin, bass viol and organ/continuo /3 three-part works four-part works five-part works six- and seven-part works A-B2: works for two or more bass viols A-BA: works for bastarda A-B1: works for solo bass viol A-B/Bc: works for solo viola da gamba and continuo/bass A-CS: consort songs A-DI: Divisions on a ground file 03: Anon (with introduction); tablature tunings beginning with ‘d’ file 04: Anon; tablature tunings beginning with ‘e’ file 05: Anon; tablature tunings beginning with ‘f’ file 06: Select tables: Hengrave Hall MSS; Le Strange MSS; Playford A (= airs, staff notation); Playford T (= tablature pieces); AB = Playford, Apollo’s Banquet (1st series) Index of Composer Names files A-Z: Alphabetical Index by Composer INTRODUCTION (by Gordon Dodd) Indexing within the Viola da Gamba Society began with the gift by Robert Donington of the card index which he had assembled while writing his thesis on English instrumental music,1 and which was maintained by Nathalie Dolmetsch until, in 1965, the material was entrusted to Gordon Dodd. -

Thomas Tallis the Complete Works

Thomas Tallis The Complete Works Tallis is dead and music dies. So wrote William Byrd, Tallis's most distinguished pupil, capturing the esteem and veneration in which Tallis was held by his fellow composers and musical colleagues in the 16th century and, indeed, by the four monarchs he served at the Chapel Royal. Tallis was undoubtedly the greatest of the 16th century composers; in craftsmanship, versatility and intensity of expression, the sheer uncluttered beauty and drama of his music reach out and speak directly to the listener. It is surprising that hitherto so little of Tallis's music has been regularly performed and that so much is not satisfactorily published. This series of ten compact discs will cover Tallis's complete surviving output from his five decades of composition, and will include the contrafacta, the secular songs and the instrumental music - much of which is as yet unrecorded. Great attention is paid to performance detail including pitch, pronunciation and the music's liturgical context. As a result new editions of the music are required for the recordings, many of which will in time be published by the Cantiones Press. 1 CD 1 Music for Henry VIII This recording, the first in the series devoted to the complete works of Thomas Tallis, includes church music written during the first decade of his career, probably between about 1530 and 1540. Relatively little is known about Tallis’s life, particularly about his early years. He was probably born in Kent during the first decade of the sixteenth century. When we first hear of him, in 1532, he is organist of Dover Priory, a small Benedictine monastery consisting of about a dozen monks. -

(Ornamental) Strokes in English Virginalist Music: a Brief Chronological Survey Desmond Hunter

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 6 Number 1 Spring The Application of (Ornamental) Strokes in English Virginalist Music: a Brief Chronological Survey Desmond Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Hunter, Desmond (1996) "The Application of (Ornamental) Strokes in English Virginalist Music: a Brief Chronological Survey," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.06 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renaissance Ornamentation The Application of (Ornamental) Strokes in English Virginalist Music: a Brief Chronolo- gical Survey Desmond Hunter Signs in the form of oblique strokes were used by the virginalists to indicate graces.1 Only one sign, the double stroke (^), enjoyed widespread currency. It appears in virtually every source of English keyboard music of the virginalist era, but surprisingly is not explain- ed by any contemporary English theorist. The sign appears also in various 17th-century north-German sources and is mentioned by Reincken in his Hortus Musicus (1687): "two strokes II denote a shake which impinges on a note from above."2 The association of the double stroke with a form of shake is suggested by the application of the sign in several 16th-century sources of English keyboard music and is one which continued throughout the virginalist era. -

Early English Organ Music: Some Contributions from The

119 /HQlJ EARLY ENGLISH ORGAN MUSIC: SOME CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MULLINER BOOK OF W. BLITHEMAN, T. TALLIS AND J. TAVERNER, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH, D. BUXTEHUDE, M. DURUFLI*, C. FRANCK, G. FRESCOBALDI, J. J. FROBERGER, P. HINDEMITH, 0. MESSIAEN, M. REGER, J. H. TALLIS, AND C.-M. WIDOR DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By David Michael Lowry, B. M., S. M. M. Denton, Texas December, 1977 Lowry, David Michael, Early English Organ Music: Some Contributions from the Mulliner Book of Blitheman, T. Tallis, and J. Taverner, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works of J. S. Bach, D. Buxtehude, M. Durufle', C. Franck, G. Frescobaldi, J. J. Froberger, P. Hindemith, 0. Messiaen, M. Reger, J. H. Tallis, and C«-M. Widor. Doctor of Musical Arts (Organ Performance), December, 1977, pp. 35, bibliography, 5 figures,- 23 titles. The lecture recital was given April 16, 1971. An Excellent Meane, six settings of Gloria Tibi Trinitas, Eterne rerum conditor, and Te Deum laudamus by William Blitheman, In Nomine by John Taverner, and Ecce tempus idonem by Thomas Tallis were performed, together with a choir of four men's voices, following a lecture on various aspects of organ music in early Tudor England. In addition to the lecture recital, three other public recitals, all solo programs, were performed. The first solo recital, including works of Dietrich Buxtehude, Johann Sebastian Bach, Paul Hindemith, and Max Reger, was performed on March 14, 1971. -

Early Music Library Early Music Library

GB£ EARLY MUSIC LIBRARY EARLY MUSIC LIBRARY The titles in this series are supplied as sets of scores, according to the number of parts, so a four-part work comes with four scores, etc.; 8-part titles come with one full score and 4 copies or the music for each choir. For larger events the scores in this series are available in sets of 10; since the series began we have found that many organisers of summer schools have taken advantage of this possibility for their events, especially as the cost is very reasonable. CLEFS: The default for inner parts (alto/tenor range) is the treble-transposing clef (treble clef with a little “8”). However, all titles are now also available in versions for viols, with the same inner parts printed in the alto clef. To order any title in these clefs, just substitute VML for EML in the order code. All titles in the series may be bought individually. We also have special prices for those who wish to purchase the complete set, or all the pieces for a specific number of parts. SPECIAL OFFERS ON COMPLETE SETS 1. All the 3-part music (65 titles), £95 2 All the 4-part music (95 titles), £105 3. All the 5-part music (50 titles). £75 4. All the 6-part music (12 titles) £30 5. All the double-choir music (28 titles in 8 parts, except for one 7-part, one 10-part), £75 6. All the music for 2 high instruments and continuo (9 titles), £20 7. All 282 titlesin the series (cover price around £800) for a mere £290 All these prices are exclusive of postage LONDON PRO MUSICA EDITION www.londonpromusica.com 1 EARLY MUSIC LIBRARY EML 101 FRANCESCO LANDINI, 2 Ballate (Gram piant' EML 128 JEAN RICHAFORT, 2 Chansons (D'amour je suis agli occhi and Charo singnor) for 3 voices or instr. -

Full Contents…(PDF)

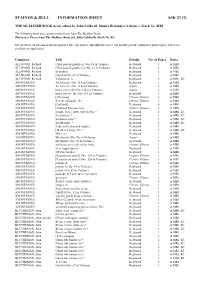

STAINER & BELL INFORMATION SHEET ASK 23 (1) THE MULLINER BOOK newly edited by John Caldwell. Musica Britannica Volume 1. Stock No. MB1 The following book also contains some items from The Mulliner Book: Thirty-five Pieces from The Mulliner Book (ed. John Caldwell). Stock No. K3 Except where an asterisk is shown against a title, our archive and offprint service can usually provide authorised photocopies. Prices are available on application. Composer Title Details No. of Pages Notes ALLWOOD, Richard Claro pascali gaudio (i) (No. 18 in Volume) Keyboard 1 in MB1 ALLWOOD, Richard Claro pascali gaudio (ii) (No. 21 in Volume) Keyboard 2 in MB1 ALLWOOD, Richard In nomine Keyboard 2 in MB1 ALLWOOD, Richard Untitled (No. 42 in Volume) Keyboard 1 in MB1 ALLWOOD, Richard Voluntarye, A Keyboard 2 in MB1, K3 ANONYMOUS As I deserve (No. 118 in Volume) Keyboard 1 in MB1 ANONYMOUS As I deserve (No. 118a in Volume) 4-part 2 in MB1 ANONYMOUS bitter sweet, the (No. 114a in Volume) 4-part 2 in MB1 ANONYMOUS bytter sweete, the (No. 114 in Volume) Keyboard 1 in MB1 ANONYMOUS [Chi passa] Cittern / Gittern 2 in MB1 ANONYMOUS frenche galliarde, The Cittern / Gittern 3 in MB1 ANONYMOUS [Galliard] Keyboard 4 in MB1 ANONYMOUS [Galliard: Passamezzo] Cittern / Gittern 2 in MB1 ANONYMOUS I smyle to see howe yow devyse * Keyboard 1 in MB1, K3 ANONYMOUS La bounette * Keyboard 1 in MB1, K3 ANONYMOUS La doune cella * Keyboard 1 in MB1, K3 ANONYMOUS La shy myze * Keyboard 1 in MB1, K3 ANONYMOUS Lyke as the chayned wyghte Keyboard 1 in MB1 ANONYMOUS [Maiden’s Song, The] * Keyboard 2 in MB1, K3 ANONYMOUS Miserere Keyboard 1 in MB1 ANONYMOUS My friends (No. -

Download Lo-Res Booklet

40 More sweet to hear 1 Organs and Voices of Tudor England Magnus Williamson – Organ The Choir of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge directed by Geoffrey Webber 2 And, so that young men as much as maidens, and old men as well as children, might 39 praise the Lord of Heaven and praise him in the height – not merely in drumming Editions used in this recording and dancing, but with strings and pipe, and pipes of organs moreover, as well as John Caldwell (ed.), Early Tudor Organ Music, I: Music for the Offi ce, Early English Church Music 6 (London: Stainer & Bell/British Academy, 1965) (tracks 1, 2 and 3); Denis Stevens with well-tuned cymbals – he had a pair of organs made whereof (it was thought) (ed.), Early Tudor Organ Music, II: Music for the Mass, EECM 10 (London, 1967) (track 4); Denis an example more beautiful to behold, more sweet to hear, and more ingenious in Stevens (ed.), The Mulliner Book, Musica Britannica 1 (London: Stainer & Bell/Royal Musical its construction could not readily be found in any monastery throughout the whole Association, 2/1954) (tracks 3, 6, 9–13, 15); John Caldwell (ed.), Tudor Keyboard Music c. 1520–80, realm. MB 66 (London: Stainer & Bell/Musica Britannica Trust, 1995) (tracks 5, 7–8, 14–15); Robin Langley (ed.), English Organ Music, 7: The Duet Repertoire 1530–1830 (London: Novello, 1988) Item ut haberent tam juvenes quam virgines, quam senes etiam simul cum junioribus, etsi (tracks 16 and 20). Magnus Williamson prepared faburden and chant verses in consultation with non in tympano et choro, in cordis tamen et organo, in organorumque fi stulis, velut in John Caldwell (track 1) and John Harper (tracks 2–3), as well as metrical psalm verses (track 15).