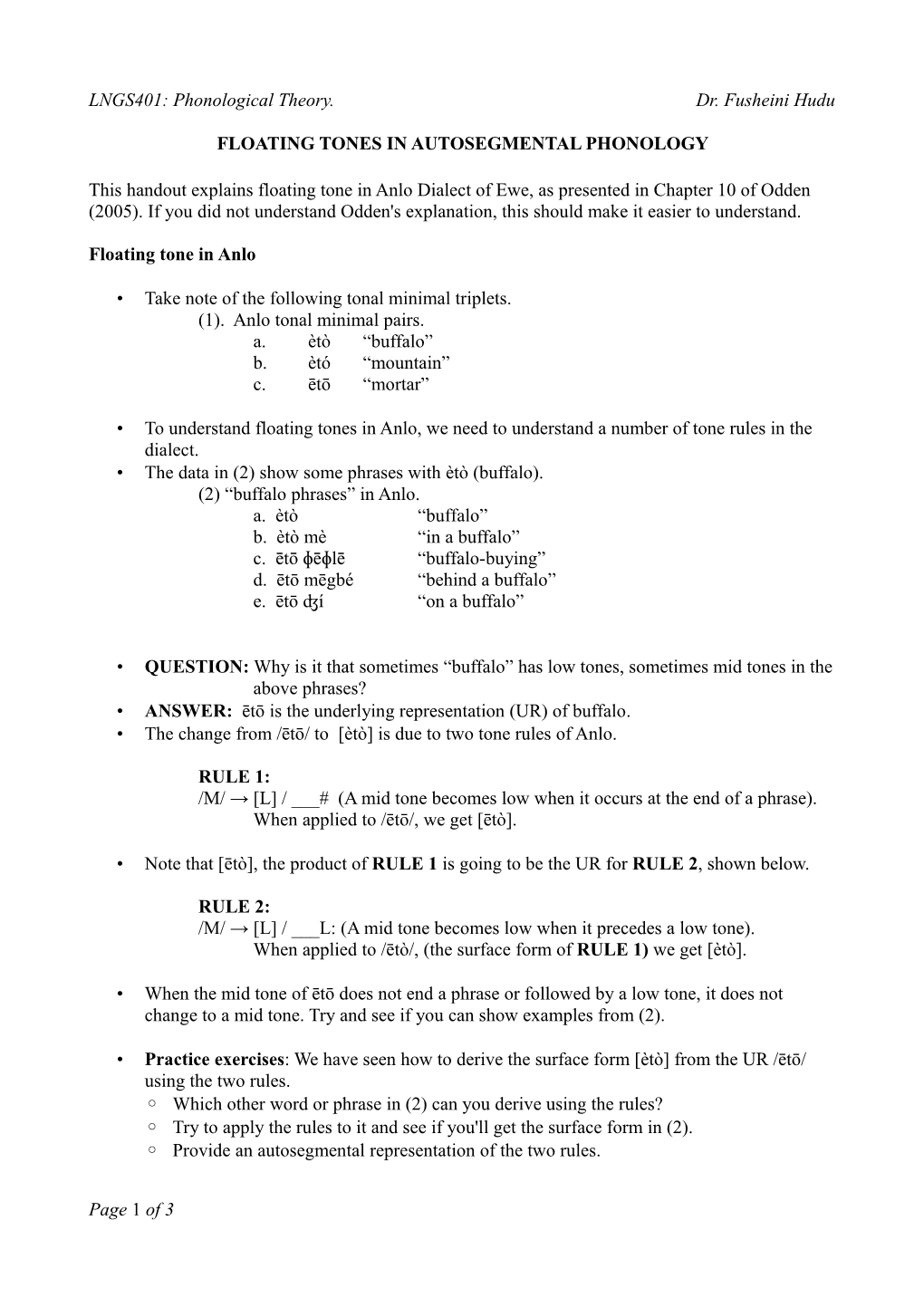

LNGS401: Phonological Theory. Dr. Fusheini Hudu FLOATING TONES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Corpus Study of the 3 Tone Sandhi in Standard Chinese

A Corpus Study of the 3 rd Tone Sandhi in Standard Chinese Yiya Chen 1, Jiahong Yuan 2 1 Department of Linguistics, Radboud University Nijmegen 2 Department of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania [email protected], [email protected] (Zhang 1988, Shih 1997, M. Chen 2000, Chen 2003, Chen Abstract 2004). Speer et al. (1989) show that listeners are indeed In Standard Chinese, a Low tone (Tone3) is often realized sensitive to a constituent’s phrasal structure in judging the application of the 3 rd tone Sandhi to constituents which could with a rising F0 contour before another Low tone, known as the 3rd tone Sandhi. This study investigates the acoustic be ambiguous between an underlying Rising tone and a characteristics of the 3rd tone Sandhi in Standard Chinese Sandhi Rising tone. Their results suggest the possibility that the higher linguistic boundary it is between two Low tones, using a large telephone conversation speech corpus. Sandhi rd Rising was found to be different from the underlying Rising the less likely the 3 tone sandhi rule is applied. With regard tone (Tone2) in bi-syllabic words in two measures: the to the difference between the underlying Rising tone and the Sandhi Rising tone, Peng (2000) show that the F0 maximum magnitude of the F 0 rising and the time span of the F 0 rising. We also found different effects of word frequency on Sandhi of SR is lower than R. Furthermore, in fast speech, a Sandhi Rising and the underlying Rising tones. Finally, for tri- Rising tone may flatten and show no apparent F0 rise (Kuo, syllabic constituents with Low tone only, constituent Xu, and Yip, to appear). -

Can Low Tone Trigger Velarization? Ben Hermans and Marc Van Oostendorp, Meertens Institute [email protected] [email protected]

Can Low Tone trigger Velarization? Ben Hermans and Marc van Oostendorp, Meertens Institute [email protected] [email protected] In many dialects of the Ripuarian area historically coronal consonants are velarized in the coda. In most dialects this has no effect on the tone, in the sense that the original tone is preserved. Cologne, for instance, is a representative case. In this dialect the form [wiŋ2] ‘wine’ has preserved its original accent 2 (≅ level high tone on the two moras of the rhyme). The fact that accent 2 is the original tone in this form is shown by the many dialects that still have this accent. There is a small group of dialects where velarization only applies if the rhyme has accent 1. These dialects have alternations of the following type: (1) bru:n2 ‘brown’, uninflected bruŋ1 ‘brown, fem. sg.’ Dialectologists usually claim that the dialects where velarization only applies under accent 1 represent the original situation (Wiesinger 1970, Schirmunsky 1962). This seems to indicate that accent 1 originally functioned as a trigger for velarization. Since accent 1 consists of a sequence of H+L, this again suggests that Low Tone somehow implies Velarity. If this were true, it would be highly interesting for at least two reasons. Firstly, it seems to create a paradox when it is related to two other well known correlations. On the one hand, we know that velars tend not to be voiced. Dutch, for instance, does not allow a voiced velar stop. This seems to indicate that Voice exludes Velarity. -

The Phonological Domain of Tone in Chinese: Historical Perspectives

THE PHONOLOGICAL DOMAIN OF TONE IN CHINESE: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES by Yichun Dai B. A. Nanjing University, 1982 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGRFE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the pepartment of Linguistics @ Yichun Dai 1991 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1991 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Yichun Dai DEGREE: Master of Arts (Linguistics) TITLE OF THESIS : The Phonological Domain of Tone in Chinese: Historical Perspectives EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman: Dr. R. C. DeArmond ----------- Dr. T. A. Perry, Senior ~aisor Dr. N. J. Lincoln - ................................... J A. Edmondson, Professor, Department of foreign Languages and Linguistics, University of Texas at Arlington, External Examiner PARTIAL COPYR l GHT L l CENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University L ibrary, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Author: (signature) (name 1 Abstract This thesis demonstrates how autosegmental licensing theory operates in Chinese. -

How to Study a Tone Language, with Exemplification from Oku (Grassfields Bantu, Cameroon)

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2010) How To Study a Tone Language, with exemplification from Oku (Grassfields Bantu, Cameroon) Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley DRAFT • August 2010 • Comments Welcome 1. Introduction On numerous occasions I have been asked, “How does one study a tone language?” Or: “How can I tell if my language is tonal?” Even seasoned field researchers, upon confronting their first tone system, have asked me: “How do I figure out the number of tones I have?” When it comes to tone, colleagues and students alike often forget everything they’ve learned about discovering the phonology of a language and assume that tone is somehow different, that it requires different techniques or expertise. Some of this may derive from an incomplete understanding of what it means to be a tone system. Prior knowledge of possible tonal inventories, tone rules, and tone- grammar interfaces would definitely be helpful to a field researcher who has to decipher a tone system. However, despite such recurrent encounters, general works on tone seem not to answer these questions—specifically, they rarely tell you how to start and how to discover. I sometimes respond to the last question, “How do I figure out the number of tones I have?”, by asking in return, “Well, how would you figure out the number of vowels you have?” Hopefully the answer would be something like: “I would get a word list, starting with nouns, listen carefully, transcribe as much detail as I can, and then organize the materials to see if I have been consistent.” (I will put off until §5 commentary concerning the use of speech software as an aid in linguistic discovery.) Although I don’t think the elicitation techniques that one applies in studying segmental vs. -

Palatalization/Velar Softening: What It Is and What It Tells Us About the Nature of Language Morris Halle

Palatalization/Velar Softening: What It Is and What It Tells Us about the Nature of Language Morris Halle This study proposes an account both of the consonantal changes in- volved in palatalization/velar softening and of the fact that this change is encountered before front vowels. The change is a straightforward case of feature assimilation provided that segments/phonemes are viewed as complexes of features organized into the ‘‘bottle brush’’ model illustrated in example (4) and elsewhere in the text, and that the universal set of features includes, in addition to the familiar binary features, six unary features, which specify the designated articulator(s) for every segment (not only for consonants). Keywords: phonetics, palatalization, velar softening, features, articula- tors For Ken Stevens, friend and colleague, on his 80th birthday My purpose in this study is to present an account of the very common alternation between dorsal and coronal consonants often referred to as palatalization or velar softening. This alternation, exemplified by English electri[k] ϳ electri[s]ity, occurs most often before front vowels. In spite of its extremely common occurrence in the languages of the world, to this time there has been no proper account of palatalization that would relate it to the other properties of language, in particular, to the fact that it is found most commonly before front vowels. In the course of working on these remarks, it became clear to me that palatalization raises numerous theoretical questions about which there is at present no agreement among phonologists. Since these include matters of the most fundamental importance for phonology, I start by exten- sively discussing the main issues and the views on them that seem to me most persuasive at this time (section 1). -

Chrau Register and the Transphonologization of Voicing

CHRAU REGISTER AND THE TRANSPHONOLOGIZATION OF VOICING Tạ Thành Tấn1, Marc Brunelle2, Nguyễn Trần Quý3 1,2 University of Ottawa, 3 Hồ Chí Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] ABSTRACT developed from voiceless and voiced obstruents modal and breathy respectively; this does not entail Chrau, a Mon-Khmer language of southern Vietnam, that voice quality is primary. Impressionistically, the has been described as preserving a voicing contrast in Chrau dialect described here seems relatively onset stops. Instead of voicing, closely related conservative as breathy register stops can optionally languages have a register contrast in which voiced be voiced (italicized in Table 1). and voiceless stops have respectively evolved into breathy and modal registers. Table 1: Chrau consonants Unexpectedly, the Chrau dialect investigated in p t c k Ɂ this paper has a register system based on f0, voice pʰ tʰ cʰ kʰ quality and vowel quality, just like its sister b/p̤̤ ̤ d/t ̤ ɟ/c ̤ ɡ/k ̤ languages. However, onset stop voicing is not fully ɓ ɗ neutralized: stops have a short positive VOT in the s h modal register, but in the breathy register, they either m n ɲ ŋ have closure voicing or a VOT slightly longer than w l, r j modal register stops. There is no evidence for an acoustic trade-off between voicing and register cues. Starting with Haudricourt (1965), early diachronic The preservation of VOT differences in onset stops accounts of registrogenesis adopted the view that it is suggests that Chrau has a conservative register the ‘laxness’ of the voiced stops that triggered the system. -

The Phonology of Tone and Intonation

This page intentionally left blank The Phonology of Tone and Intonation Tone and Intonation are two types of pitch variation, which are used by speak- ers of many languages in order to give shape to utterances. More specifically, tone encodes morphemes, and intonation gives utterances a further discoursal meaning that is independent of the meanings of the words themselves. In this comprehensive survey, Carlos Gussenhoven provides an up-to-date overview of research into tone and intonation, discussing why speakers vary their pitch, what pitch variations mean, and how they are integrated into our grammars. He also explains why intonation in part appears to be universally understood, while at other times it is language-specific and can lead to misunderstandings. The first eight chapters concern general topics: phonetic aspects of pitch mod- ulation; typological notions (stress, accent, tone, and intonation); the distinction between phonetic implementation and phonological representation; the paralin- guistic meaning of pitch variation; the phonology and phonetics of downtrends; developments from the Pierrehumbert–Beckman model; and tone and intona- tion in Optimality Theory. In chapters 9–15, the book’s central arguments are illustrated with comprehensive phonological descriptions – partly in OT – of the tonal and intonational systems of six languages, including Japanese, French, and English. Accompanying sound files can be found on the author’s web site: http://www.let.kun.nl/pti Carlos Gussenhoven is Professor and Chair of General and Experimental Phonology at the University of Nijmegen. He has previously published On the Grammar and Semantics of Sentence Accents (1994), English Pronunciation for Student Teachers (co-authored with A. -

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 21, Number 3, December 1990

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 21, Number 3, December 1990 CONTEXTUAL LABIALIZATION IN NA WURI* Roderic F. Casali Ghana Institute of Linguistics Literacy and Bible Translation and UCLA A spectrographic investigation into the non-contrastive labialization of consonants before round vowels in Nawuri (a Kwa language of Ghana) sup ports the notion that this labialization is the result of a phonological, feature spreading rule and not simply an automatic transitional process. This as sumption is further warranted in that it allows for a more natural treatment of some other phonological processes in the language. The fact that labial ization before round vowels is generally not very audible is explained in terms of a principle of speech perception. A final topic addressed is the question of why (both in Nawuri and apparently in a number of other Ghanaian languages as well) contextual labialization does tend to be more perceptible in certain restricted environments. o. Introduction This paper deals with the allophonic labialization of consonants before round vowels in Nawuri, a Kwa language of Ghana.! While such labialization is gener ally not very audible, spectrographic evidence suggests that it is strongly present, * The spectrograms in this study were produced at the phonetics lab of the University of Texas at Arlington using equipment provided through a grant of the Permanent University Fund of the University of Texas system. I would like to thank the following people for their valuable comments and suggestions: Joan Baart, Don Burquest, Mike Cahill, Jerry Edmondson, Norris McKinney, Bob Mugele, Tony Naden, and Keith Snider. I would also like to express my appreciation to Russell Schuh and an anonymous referee for this journal for their helpful criticism of an earlier version, and to Mary Steele for some helpful discussion concerning labialization in Konkomba. -

Teaching and Learning the Tones of Mandarin Chinese Introduction

Scottish Languages Review Issue 24, Winter 2011-12, 43-50 Teaching and learning the tones of Mandarin Chinese Rachel Tsai St George’s School for Girls Abstract: This article explores issues around the learning of the four tones in Mandarin Chinese, particularly by native speakers of English. It introduces the reader to the nature of the tones and outlines current teaching practice in common use. It then explores difficulties encountered at the early learning stages. It is shown that native speakers of non-tonal languages need to develop and exercise new areas of the brain through repeated practising of tones, and that musical ability makes it easier to learn the tones. Keywords: Mandarin Chinese; tones; pinyin Introduction New students of Mandarin Chinese often find tones confusing and difficult to learn, leading to frustration, disappointment and neglect. This article focuses on the very early stages of learning the tones of Mandarin Chinese, that is, on how students become familiar with identifying the tones when they hear them, and how they learn to vocalise the tones in individual words or syllables. What are tones? Tones refer to the pitch made when a word is spoken. For example, in English a word, “dog” for example, could be said with the voice at a constant high pitch, or with the pitch starting low and ending high. Whichever way “dog” is said in English it still means the same thing, i.e. an animal that barks. But in Mandarin the same is not true: If a word, “ma” for example, is said with the voice at a constant high pitch it means “mother”, but if “ma” is said with the pitch starting low and ending high, then it means “horse”. -

Tone and Non-Tone Languages: an Alternative to Language Typology and Parameters*

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 5.4:891-924, 2004 2004-0-005-004-000098-1 Tone and Non-tone Languages: * An Alternative to Language Typology and Parameters San Duanmu University of Michigan Linguists often classify languages into various types. In generative phonol- ogy, language typology is usually translated into parameters, such as the parame- ter for trochaic vs. iambic feet, or the parameter for syllable counting vs. mora counting. Focusing on the typology of tone and non-tone languages, I argue that the typological or parametric approach has four problems. First, it does not offer a clear-cut classification. Second, it does not capture similarities between different language types. Third, it does not capture differences within a given language type. Fourth, it does not offer a good guide for research. As an alternative, I offer a the- ory in which there is no typology or parameters. Instead, languages differ in their selection of various phonological inventories (vowel inventory, consonant inven- tory, tonal inventory, etc.). Each inventory selection has a specific set of proper- ties, and the interactions among various inventory selections give the overall properties of a given language. The present theory is simpler, offers a better guide for research, and offers a better understanding of language differences and lan- guage universals. Key words: tone, typology, parameters 1. Introduction Linguists often classify languages into various types, such as tone vs. non-tone lan- guages, stress vs. non-stress languages, trochaic vs. iambic languages, isolating vs. inflectional languages, SVO vs. SOV languages, and so on. In generative phonology, language typology is usually translated into parameters, such as the parameter for tro- chaic vs. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Sound Change in San Francisco English Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6qz10226 Author Moonwomon, Birch Publication Date 1991 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Sound Change in San Francisco English By Birch Moonwomon B A (Sonoma State University) 1981 M.A. (Sonoma State University) 1983 M.A. (University of California) 1986 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of die requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA at BERKELEY Approved: iviaitaiaiii .Tf^rv^.. ............. YA?/?/ . PfNJkp- • ... ih y j. V.... |'JxJIa UAaU»- fLh'UaU, 2 ■i/ I*)?I Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. 1 Sound Change in San Francisco English by Birch Moonwomon Abstract This is a sociolinguisdc study of sound change in progress in San Francisco White English. Both phonemic and subphonemic recategorizations have taken place in the phonology in the last 50 years. The dissertation repeats on observations of variation in the speech of 14 working class and middle class San Franciscan women, ranging in age from 22 to 74. Vowel movements involving /ae/, /a/, and h i (treated as principal variables (x), (xN), (a), (ar), (o), (ol), and (or)) are traced through apparent time. /x/ before nasal consonants, treated as the variable (xN), is becoming increasingly tense. The development of complementarity between /x/ in this environment and /x/ elsewhere is reflected in the gradual separation of (xN) from (x) in vowel space over time. There is also sound change for low, nonperipheral (x); (xS), that is, /x/ before fricatives, is centralizing. -

1 the Phonology of Mixteco's

THE PHONOLOGY OF MIXTECO'S FLOATING HIGH TONES: THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS BERNARD TRANEL University of California, Irvine <[email protected]> 1. INTRODUCTION This paper provides a cross-theoretical comparison of the treatment of floating high tones in Mixteco, a language of Southern Mexico studied by Kenneth Pike in the 1930's and 40's. Such a case study proves instructive in three major ways. First, it justifies the recent theoretical trend to move away from rule-based phonology to constraint-based phonology. Secondly, it raises interesting theoretical issues within the nascent constraint-based approach. Finally, it brings about new perspectives on our understanding of tonal phonology and the morphology of floating elements. In a nutshell, the facts of relevance in Mixteco are the following: a morpheme-final floating high tone anchors into the next morpheme (if no pause intervenes), but its landing site varies depending on the host morpheme's own tonal and segmental make-up. Thus, the floating tone does not automatically dock onto the first tone-bearing element of its host, as one might expect in such tone sandhi configurations. Instead, it prefers to attach to the first low-tone or high-tone vowel, even if it requires skipping an intervening mid-tone vowel. This preference can however be thwarted in some cases. For example, a medial glottal stop in effect prevents a floating high tone from ignoring an initial mid-tone vowel in favor of a subsequent low-tone or high-tone vowel. Another important characteristic of floating high tones in Mixteco is that they are never phonetically realized within their own lexical morphemes.