Presolar Cloud Collapse and the Formation and Early Evolution of the Solar Nebula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

Exors and the Stellar Birthline Mackenzie S

A&A 600, A133 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630196 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics EXors and the stellar birthline Mackenzie S. L. Moody1 and Steven W. Stahler2 1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 December 2016 / Accepted 23 February 2017 ABSTRACT We assess the evolutionary status of EXors. These low-mass, pre-main-sequence stars repeatedly undergo sharp luminosity increases, each a year or so in duration. We place into the HR diagram all EXors that have documented quiescent luminosities and effective temperatures, and thus determine their masses and ages. Two alternate sets of pre-main-sequence tracks are used, and yield similar results. Roughly half of EXors are embedded objects, i.e., they appear observationally as Class I or flat-spectrum infrared sources. We find that these are relatively young and are located close to the stellar birthline in the HR diagram. Optically visible EXors, on the other hand, are situated well below the birthline. They have ages of several Myr, typical of classical T Tauri stars. Judging from the limited data at hand, we find no evidence that binarity companions trigger EXor eruptions; this issue merits further investigation. We draw several general conclusions. First, repetitive luminosity outbursts do not occur in all pre-main-sequence stars, and are not in themselves a sign of extreme youth. They persist, along with other signs of activity, in a relatively small subset of these objects. -

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Impact of Supernovae on Molecular Cloud Evolution Dynamics and Structure

Impact of Supernovae on Molecular Cloud Evolution Dynamics and Structure Bastian K¨ortgen1, Daniel Seifried1, and Robi Banerjee1 1Hamburger Sternwarte, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Introduction We perform numerical simulations of colliding streams of the WNM, including magnetic fields and self{gravity, to analyse the formation and evolution of molecular clouds subject to supernova feedback from massive stars. Simulation Setup The Supernova Subgrid Model The equations of MHD together with selfgravity and heating and cooling are evolved in time using the The supernova feedback is included into the model by means of a Sedov blast FLASH code [Fryxell et al., 2000]. We use a constant heating rate Γ and the cooling function Λ according to wave solution. We define a volume of radius R = 1 pc centered on the sink [Koyama and Inutsuka, 2000] and [V´azquez-Semadeni et al., 2007]. The table below lists the initial conditions. particle. Within this volume each grid cell is assigned a certain radial veloc- ity vc. This velocity depends on the kinetic energy input. Additionally we U Sink Particle Parameter Value Parameter Value inject thermal energy, which then gives the total amount of injected energy of E = 1051 erg with 65 % thermal and 35 % kinetic energy according to the Flow Mach number Mf 2.0 Alfv´en velocity va [km/s] 5.8 sn Sedov solution. The cell velocity is Turbulent Mach number Ms 0.5 Alfv´enic Mach number Ma 1.96 r vc = Ush Temperature [K] 5000 Plasma Beta β = Pth=PB 1.93 R Number density n cm−3 1.0 Flow Length [pc] 112 Figure 1: Schematic of the where U is the shock velocity, depending on the kinetic energy input. -

Effect of the Solar Wind Density on the Evolution of Normal and Inverse Coronal Mass Ejections S

A&A 632, A89 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201935894 & c ESO 2019 Astrophysics Effect of the solar wind density on the evolution of normal and inverse coronal mass ejections S. Hosteaux, E. Chané, and S. Poedts Centre for mathematical Plasma-Astrophysics (CmPA), Celestijnenlaan 200B, KU Leuven, 3001 Leuven, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] Received 15 May 2019 / Accepted 11 September 2019 ABSTRACT Context. The evolution of magnetised coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and their interaction with the background solar wind leading to deflection, deformation, and erosion is still largely unclear as there is very little observational data available. Even so, this evolution is very important for the geo-effectiveness of CMEs. Aims. We investigate the evolution of both normal and inverse CMEs ejected at different initial velocities, and observe the effect of the background wind density and their magnetic polarity on their evolution up to 1 AU. Methods. We performed 2.5D (axisymmetric) simulations by solving the magnetohydrodynamic equations on a radially stretched grid, employing a block-based adaptive mesh refinement scheme based on a density threshold to achieve high resolution following the evolution of the magnetic clouds and the leading bow shocks. All the simulations discussed in the present paper were performed using the same initial grid and numerical methods. Results. The polarity of the internal magnetic field of the CME has a substantial effect on its propagation velocity and on its defor- mation and erosion during its evolution towards Earth. We quantified the effects of the polarity of the internal magnetic field of the CMEs and of the density of the background solar wind on the arrival times of the shock front and the magnetic cloud. -

Star Formation in the “Gulf of Mexico”

A&A 528, A125 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200912671 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Star formation in the “Gulf of Mexico” T. Armond1,, B. Reipurth2,J.Bally3, and C. Aspin2, 1 SOAR Telescope, Casilla 603, La Serena, Chile e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 640 N. Aohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA e-mail: [reipurth;caa]@ifa.hawaii.edu 3 Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 9 June 2009 / Accepted 6 February 2011 ABSTRACT We present an optical/infrared study of the dense molecular cloud, L935, dubbed “The Gulf of Mexico”, which separates the North America and the Pelican nebulae, and we demonstrate that this area is a very active star forming region. A wide-field imaging study with interference filters has revealed 35 new Herbig-Haro objects in the Gulf of Mexico. A grism survey has identified 41 Hα emission- line stars, 30 of them new. A small cluster of partly embedded pre-main sequence stars is located around the known LkHα 185-189 group of stars, which includes the recently erupting FUor HBC 722. Key words. Herbig-Haro objects – stars: formation 1. Introduction In a grism survey of the W80 region, Herbig (1958) detected a population of Hα emission-line stars, LkHα 131–195, mostly The North America nebula (NGC 7000) and the adjacent Pelican T Tauri stars, including the little group LkHα 185 to 189 located nebula (IC 5070), both well known for the characteristic shapes within the dark lane of the Gulf of Mexico, thus demonstrating that have given rise to their names, are part of the single large that low-mass star formation has recently taken place here. -

SXP 1062, a Young Be X-Ray Binary Pulsar with Long Spin Period⋆

A&A 537, L1 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118369 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor SXP 1062, a young Be X-ray binary pulsar with long spin period Implications for the neutron star birth spin F. Haberl1, R. Sturm1, M. D. Filipovic´2,W.Pietsch1, and E. J. Crawford2 1 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße, 85748 Garching, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith South DC, NSW1797, Australia Received 31 October 2011 / Accepted 1 December 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) is ideally suited to investigating the recent star formation history from X-ray source population studies. It harbours a large number of Be/X-ray binaries (Be stars with an accreting neutron star as companion), and the supernova remnants can be easily resolved with imaging X-ray instruments. Aims. We search for new supernova remnants in the SMC and in particular for composite remnants with a central X-ray source. Methods. We study the morphology of newly found candidate supernova remnants using radio, optical and X-ray images and inves- tigate their X-ray spectra. Results. Here we report on the discovery of the new supernova remnant around the recently discovered Be/X-ray binary pulsar CXO J012745.97−733256.5 = SXP 1062 in radio and X-ray images. The Be/X-ray binary system is found near the centre of the supernova remnant, which is located at the outer edge of the eastern wing of the SMC. The remnant is oxygen-rich, indicating that it developed from a type Ib event. -

Implications of a Hot Atmosphere/Corino from ALMA Observations Toward NGC 1333 IRAS 4A1

The Astrophysical Journal, 872:196 (14pp), 2019 February 20 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aaffda © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Implications of a Hot Atmosphere/Corino from ALMA Observations toward NGC 1333 IRAS 4A1 Dipen Sahu1,2,3, Sheng-Yuan Liu2 , Yu-Nung Su2, Zhi-Yun Li4, Chin-Fei Lee2 , Naomi Hirano2, and Shigehisa Takakuwa2,5 1 Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Sarjapur Main Road, 2nd Block, Koramangala, Bangalore-560034, India; [email protected] 2 Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 11F of AS/NTU Astronomy-Mathematics Building, No.1, Section 4, Roosevelt Rd, Taipei 10617, Taiwan, R.O.C. 3 Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad-380009, India 4 Astronomy Department, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA 5 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-35 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan Received 2018 October 24; revised 2019 January 14; accepted 2019 January 16; published 2019 February 25 Abstract We report high angular resolution observations of NGC 1333 IRAS 4A, a protostellar binary including A1 and A2, at 0.84mm with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. From the continuum observations, we suggest that the dust emission from the A1 core is optically thick, and A2 is predominantly optically thin. The A2 core, exhibiting a forest of spectral lines including complex molecules, is a well-known hot corino, as suggested by previous works. More importantly, we report, for the first time, solid evidence of complex organic molecules 13 (COMs), including CH3OH, CH3OH, CH2DOH, and CH3CHO, associated with the A1 core seen in absorption. -

Predicting the Magnetic Vectors Within Coronal Mass Ejections Arriving at Earth: 2

Space Weather RESEARCH ARTICLE Predicting the magnetic vectors within coronal mass ejections 10.1002/2015SW001171 arriving at Earth: 1. Initial architecture Key Points: N. P.Savani1,2, A. Vourlidas1, A. Szabo2,M.L.Mays2,3, I. G. Richardson2,4, B. J. Thompson2, • First architectural design to predict A. Pulkkinen2,R.Evans5, and T. Nieves-Chinchilla2,3 a CME’s magnetic vectors (with eight events) 1 2 • Modified Bothmer-Schwenn CME Goddard Planetary Heliophysics Institute (GPHI), University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Maryland, USA, NASA 3 initiation rule to improve reliability Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Institute for Astrophysics and Computational Sciences (IACS), of chirality Catholic University of America, Washington, District of Columbia, USA, 4Department of Astronomy, University of • CME evolution seen by remote Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA, 5College of Science, George Mason University, Fairfax, Vancouver, USA sensing triangulation is important for forecasting Abstract The process by which the Sun affects the terrestrial environment on short timescales is Correspondence to: predominately driven by the amount of magnetic reconnection between the solar wind and Earth’s N. P. Savani, magnetosphere. Reconnection occurs most efficiently when the solar wind magnetic field has a southward [email protected] component. The most severe impacts are during the arrival of a coronal mass ejection (CME) when the magnetosphere is both compressed and magnetically connected to the heliospheric environment. Citation: Unfortunately, forecasting magnetic vectors within coronal mass ejections remain elusive. Here we report Savani, N. P., A. Vourlidas, A. Szabo, M.L.Mays,I.G.Richardson,B.J. how, by combining a statistically robust helicity rule for a CME’s solar origin with a simplified flux rope Thompson, A. -

Predictability of the Variable Solar-Terrestrial Coupling Ioannis A

https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-2020-94 Preprint. Discussion started: 26 January 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Predictability of the variable solar-terrestrial coupling Ioannis A. Daglis1,15, Loren C. Chang2, Sergio Dasso3, Nat Gopalswamy4, Olga V. Khabarova5, Emilia Kilpua6, Ramon Lopez7, Daniel Marsh8,16, Katja Matthes9,17, Dibyendu Nandi10, Annika Seppälä11, Kazuo Shiokawa12, Rémi Thiéblemont13 and Qiugang Zong14 5 1Department of Physics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece 2Department of Space Science and Engineering, Center for Astronautical Physics and Engineering, National Central University, Taiwan 3Department of Physics, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina 10 4Heliophysics Science Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 5Solar-Terrestrial Department, Pushkov Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radio Wave Propagation of RAS (IZMIRAN), Moscow, 108840, Russia 6Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 7Department of Physics, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019, USA 15 8National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO 80305, USA 9GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, Kiel, Germany 10IISER, Kolkata, India 11Department of Physics, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand 12Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan 20 13LATMOS, Universite Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France 14School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China 15Hellenic Space Center, Athens, Greece 16Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK 17Christian-Albrechts Universität, Kiel, Germany 25 Correspondence to: Ioannis A. Daglis ([email protected]) Abstract. In October 2017, the Scientific Committee on Solar-Terrestrial Physics (SCOSTEP) Bureau established a 30 committee for the design of SCOSTEP’s Next Scientific Program (NSP). -

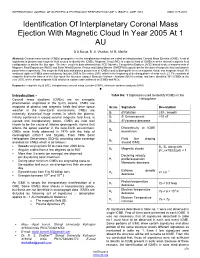

Identification of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection with Magnetic Cloud in Year 2005 at 1 AU

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 6, JUNE 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 Identification Of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection With Magnetic Cloud In Year 2005 At 1 AU D.S.Burud, R .S. Vhatkar, M. B. Mohite Abstract: Coronal mass ejection (CMEs) propagate in to the interplanetary medium are called as Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection (ICME). A set of signatures in plasma and magnetic field is used to identify the ICMEs. Magnetic Cloud (MC) is a special kind of ICMEs in which internal magnetic field configuration is similar like flux rope. We have used the data obtained from ACE Advance Composition Explorer (ACE) based in-situ measurements of Magnetic Field Experiment (MAG) and Solar Wind Electron, Proton and Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM) experiment for the data of magnetic field and plasma parameters respectively. The magnetic field data and plasma parameters of ICMEs used to distinguish them as magnetic cloud, non magnetic cloud. We analyzed eighteen ICMEs observed during January 2005 to December 2005, which is the beginning of declining phase of solar cycle 23. The analysis of magnetic field in the frames of the flux ropes like structure using a Minimum Variance Analysis (MVA) method, and have identified 30% ICMEs in the year 2005, which shows magnetic field rotation in a plane and confirmed as ICMEs with MCs. Keywords: magnetic cloud (MC), interplanetary coronal mass ejection (ICME), minimum variance analysis (MVA). ———————————————————— Introduction:- Table No: 1 Signatures used to identify ICMEs in the Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are an energetic Heliosphere phenomenon originated in the Sun‘s corona, CMEs are eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields that drive space Sr.no. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short).