THE U. S. COAST GUARD in the ARCTIC and SUB ARCTIC By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUES CURRENT ? — Please CHECK YOUR MAILING LABEL

The Official Publication of theCoast Guard Aviation Association The Ancient Order of the Pterodactyl Sitrep 2-17 Summer 2017 AOP is a non profit association of active & retired USCG aviation personnel & associates C O N T E N T S President’s Corner……………..........................2 HITRON Records 500th Drug Bust…………….... 3 Longest Serving CG Auxiliary Pilot Retires….3 Ptero ‘Butch’ Flythe Now CGAA ‘Ambassador’...4 2016 Jack Rittichier MVP Award Presented...5 2017 Service Academy Flying Team Results…...5 CG Aviator Receives Elmer Stone’s Wings…...6 The Sinking That Never Happened………...……..6 2017 Roost Tours & Registration Info..........10 Ancient Al #25 Letter to Pteros….…………...... 13 ‘Plan One Acknowledge’ & the CG Baptism..13 Ten Pound Island Wreath Laying……......……...14 AirSta Corpus Christi Highlighted…………....15 Mail Call……………………………………..………....16 CG Aviator Receives Daedalian Award...……17 ‘Above the Fog’……………………………………....18 New Aviators & ATTC Grads……...…...…...18 Membership Application/Renewal/Order Form...19 Pforty-first CGAA Roost in Atlantic City Approaching Glide Path Our pforty-first annual gathering honoring CO Ptero CAPT Eric ‘Jackie’ Gleason, Aviator 3316, and the men and women of Air Station Atlantic City will be at the Resorts Casino Hotel on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, NJ from 13-15 September. Many thanks to Pteros Jeff Pettitt, Aviator 2188, and Dale Goodreau, Aviator 1710, for graciously volunteering to serve as Roost Committee co-chairs. Please see Page ten for events and registration information. AirSta Clearwater & the AirSta Clearwater Wins CG Aeronautical Engi- Maintenance Competition neers teams participated in the 2017 Aerospace Maintenance Competition in Orlando on 25-27 April. The teams were challenged by 25 events that tested their maintenance abilities in timed trials. -

Ice Navigation Training

Training for maritime operations in polar waters-fulfillment of the Polar code Sergey Aysinov, MBA, PhD, Director of Professional development programmes Institute Head of Makarov training centre Historical Background Number of Students (2015/2016 academic year) Full time training 5168 Distance learning (all Faculties) 2712 Maritime College (all forms of education) 1376 3317 Teaching Staff (Higher Education) Professors, PH.D. Full time 431 Part time 154 Assistant Professors 221 Branches 72 International Maritime Activity The University experts participate in Russian Federation Delegations as well as IALA, ITF delegations to the regulatory organizations: International Maritime Organization (IMO) and International Labour Organization (ILO) University is a member of: . Executive Committee of International Association of Maritime Universities (IAMU); . International Maritime Lecturers Association (IMLA); . International Sail Training Association (ISTA); . International Maritime Simulator Forum (IMSF); . STENA Association of Maritime Institutions (STAMI) acting under the patronage of shipping company STENA (Sweden) Technological and Personnel resourses Makarov Training Centre: . 46 Modern training simulators, . More than 200 highly professional Engineers, Instructors, Managers, Experts, . More than 170 training programs, . 20+ years of operation, . Approval from Russian Ministry of Transport, Federal Marine and River Transport Agency, other Flag state Administrations, Certification Association “Russian Register”, Russian Maritime Register of Shipping, The Nautical Institute, and others. MTC provides professional simulator training to more than 15 000 trainees from 23+ countries annually without any boundaries. MAKAROV TRAINING CENTRE ICE NAVIGATION TRAINING Start May, 2003 Main Sailing Areas – the Baltics: - St. Petersburg - Primorsk - Vysotsk - Ust’-Luga Number of trainees: 900 + Unicom (Cyprus) – the first partner 2003-2016. What have been changed ? Regulatory base – Polar code, SOLAS and STCW amendments. -

Coast Guard Awards CIM 1560 25D(PDF)

Medals and Awards Manual COMDTINST M1650.25D MAY 2008 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK. Commandant 1900 Half Street, S.W. United States Coast Guard Washington, DC 20593-0001 Staff Symbol: CG-12 Phone: (202) 475-5222 COMDTINST M1650.25D 5 May 2008 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M1625.25D Subj: MEDALS AND AWARDS MANUAL 1. PURPOSE. This Manual publishes a revision of the Medals and Awards Manual. This Manual is applicable to all active and reserve Coast Guard members and other Service members assigned to duty within the Coast Guard. 2. ACTION. Area, district, and sector commanders, commanders of maintenance and logistics commands, Commander, Deployable Operations Group, commanding officers of headquarters units, and assistant commandants for directorates, Judge Advocate General, and special staff offices at Headquarters shall ensure that the provisions of this Manual are followed. Internet release is authorized. 3. DIRECTIVES AFFECTED. Coast Guard Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25C and Coast Guard Rewards and Recognition Handbook, CG Publication 1650.37 are cancelled. 4. MAJOR CHANGES. Major changes in this revision include: clarification of Operational Distinguishing Device policy, award criteria for ribbons and medals established since the previous edition of the Manual, guidance for prior service members, clarification and expansion of administrative procedures and record retention requirements, and new and updated enclosures. 5. ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS/CONSIDERATIONS. Environmental considerations were examined in the development of this Manual and have been determined to be not applicable. 6. FORMS/REPORTS: The forms called for in this Manual are available in USCG Electronic Forms on the Standard Workstation or on the Internet: http://www.uscg.mil/forms/, CG Central at http://cgcentral.uscg.mil/, and Intranet at http://cgweb2.comdt.uscg.mil/CGFORMS/Welcome.htm. -

Eske Brun Og Det Moderne Grønlands Tilblivelse 1932 – 64

Eske Brun og det moderne Grønlands tilblivelse 1932 – 64 Ph.d.-afhandling af Jens Heinrich, juni 2010 Hovedvejleder dr. phil., lektor Thorkild Kjærgaard, Ilisimatusarfik Bivejleder ph.d. Søren Forchhammer I tilknytning til Ilisimatusarfik/Grønlands Univesitet KVUG (Kommissionen for Videnskabelige Undersøgelser i Grønland) Forside foto – Eske Brun, ca. 1940 © Nunatta Katersugaasivia/Grønlands Nationalmuseum Johan Carl Brun Gotfred Hansen (1711-75) læge (1765-1835) Stamtræ vinhandler Kilde DBL Constantin Brun (Brun og Hansen, (1746-1836) storkøbmand Nb. - ikke alle er inkluderet) Andreas Nicolai Hansen (1798-1873) Carl Frederik Balthazar Brun Ida de Bombelles f. Brun grosserer (1784-1869) godsejer, kammerherre (1792-1857) kunstner Petrus Friederich (Fritz) Constantin Alexander Brun Carl A. A. F. J. Brun Alfred Peter Hansen Octavius Hansen James Gustav Hansen Brun (1813-1888) amtmand (1814-1893) (1824-1898) (1829-1893) (1838-1903) (1843-1912) biavler, landmand generalmajor ingeniør politiker, grosserer, politiker, etatsråd sagfører Oscar Brun Axel Brun Erik Brun Constantin Brun Charles Brun Rigmor Hansen Ingeborg Hansen (1851-1921) (1870-1958) (1867-1915) (1860-1945) (1866-1919) (1875-1948) (1873-1949) landmand, politiker læge læge diplomat amtmand, politiker Carl Brun (1897-1958) Eske Brun diplomat (1904-1987) Departementschef Gift i 1937 med Ingrid f. Winkel (1911-) Tre børn; Johan (1938-), Christian (1940-) og Ida (1942- ) Eske Brun og det moderne Grønlands tilblivelse 1932-1964 Indholdsfortegnelse Forord ................................................................................................................................................ -

Eske Brun Og Det Moderne Grønlands Tilblivelse 1932-64

Naalakkersuisut Grønlands Selvstyre INUSSUK • Arktisk forskningsjournal 1 • 2012 Eske Brun og det moderne Grønlands tilblivelse Jens Heinrich Naalakkersuisut Grønlands Selvstyre INUSSUK • Arktisk forskningsjournal 1 • 2012 Eske Brun og det moderne Grønlands tilblivelse Jens Heinrich Eske Brun og det moderne Grønlands tilblivelse 1932-64 INUSSUK - Arktisk forskningsjournal 1 - 2012 Copyright © Forfatter & Departementet for Uddannelse og Forskning, Nuuk 2012 Tilrettelæggelse: allu design - www.allu.gl Sats: Verdana Forlag: Forlaget Atuagkat ApS Tryk: AKA Print A/S, Århus 1. udgave, 1. oplag Oplag: 500 eksemplarer ISBN 97-887-92554-38-3 ISSN 1397-7431 Uddrag, herunder figurer, tabeller og citater er tilladt med tydelig kildeangivelse. Skrifter der omtaler, anmelder, citerer eller henviser til denne publikation, bedes venligst tilsendt. Skriftserien INUSSUK udgives af Departementet for Uddannelse og Forskning, Grønlands Selvstyre. Det er formålet at formidle resultater fra forskning i arktis, såvel til den grønlandske befolkning som til forskningsmiljøer i Grønland og Danmark. Skriftserien ønsker at bidrage til en styrkelse af det arktiske samarbejde, især inden for humanistisk, samfundsvidenskabelig og sundheds- videnskabelig forskning. Redaktionen modtager gerne forslag til publikationer. Redaktion Forskningskoordinator Forskningskoordinator Najâraq Paniula Lone Nukaaraq Møller Departementet for Departementet for Uddannelse og Forskning Uddannelse og Forskning Grønlands Selvstyre Grønlands Selvstyre Postboks 1029, 3900 Nuuk Postboks 1029, 3900 Nuuk Telefon: +299 34 50 00 Telefon: +299 34 50 00 Fax: +299 32 20 73 Fax: +299 32 20 73 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Publikationer i serien kan rekvireres ved henvendelse til Forlaget Atuagkat ApS Postboks 216 3900 Nuuk Email: [email protected] www.atuagkat.gl Indholdsfortegnelse Indledning • Forord af Bo Lidegaard . -

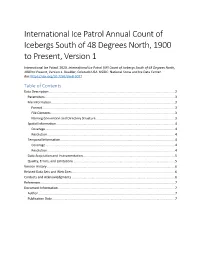

International Ice Patrol Annual Count of Icebergs South of 48 Degrees North, 1900 to Present, Version 1

International Ice Patrol Annual Count of Icebergs South of 48 Degrees North, 1900 to Present, Version 1 International Ice Patrol. 2020. International Ice Patrol (IIP) Count of Icebergs South of 48 Degrees North, 1900 to Present, Version 1. Boulder, Colorado USA. NSIDC: National Snow and Ice Data Center. doi: https://doi.org/10.7265/z6e8-3027 Table of Contents Data Description ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Parameters ................................................................................................................................................ 3 File Information ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Format ................................................................................................................................................... 3 File Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Naming Convention and Directory Structure ....................................................................................... 3 Spatial Information ................................................................................................................................... 4 Coverage .............................................................................................................................................. -

America's Undeclared Naval War

America's Undeclared Naval War Between September 1939 and December 1941, the United States moved from neutral to active belligerent in an undeclared naval war against Nazi Germany. During those early years the British could well have lost the Battle of the Atlantic. The undeclared war was the difference that kept Britain in the war and gave the United States time to prepare for total war. With America’s isolationism, disillusionment from its World War I experience, pacifism, and tradition of avoiding European problems, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved cautiously to aid Britain. Historian C.L. Sulzberger wrote that the undeclared war “came about in degrees.” For Roosevelt, it was more than a policy. It was a conviction to halt an evil and a threat to civilization. As commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces, Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy from neutrality to undeclared war. It was a slow process as Roosevelt walked a tightrope between public opinion, the Constitution, and a declaration of war. By the fall of 1941, the U.S. Navy and the British Royal Navy were operating together as wartime naval partners. So close were their operations that as early as autumn 1939, the British 1 | P a g e Ambassador to the United States, Lord Lothian, termed it a “present unwritten and unnamed naval alliance.” The United States Navy called it an “informal arrangement.” Regardless of what America’s actions were called, the fact is the power of the United States influenced the course of the Atlantic war in 1941. The undeclared war was most intense between September and December 1941, but its origins reached back more than two years and sprang from the mind of one man and one man only—Franklin Roosevelt. -

Structural Challenges Faced by Arctic Ships

NTIS # PB2011- SSC-461 STRUCTURAL CHALLENGES FACED BY ARCTIC SHIPS This document has been approved For public release and sale; its Distribution is unlimited SHIP STRUCTURE COMMITTEE 2011 Ship Structure Committee RADM P.F. Zukunft RDML Thomas Eccles U. S. Coast Guard Assistant Commandant, Chief Engineer and Deputy Commander Assistant Commandant for Marine Safety, Security For Naval Systems Engineering (SEA05) and Stewardship Co-Chair, Ship Structure Committee Co-Chair, Ship Structure Committee Mr. H. Paul Cojeen Dr. Roger Basu Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers Senior Vice President American Bureau of Shipping Mr. Christopher McMahon Mr. Victor Santos Pedro Director, Office of Ship Construction Director Design, Equipment and Boating Safety, Maritime Administration Marine Safety, Transport Canada Mr. Kevin Baetsen Dr. Neil Pegg Director of Engineering Group Leader - Structural Mechanics Military Sealift Command Defence Research & Development Canada - Atlantic Mr. Jeffrey Lantz, Mr. Edward Godfrey Commercial Regulations and Standards for the Director, Structural Integrity and Performance Division Assistant Commandant for Marine Safety, Security and Stewardship Dr. John Pazik Mr. Jeffery Orner Director, Ship Systems and Engineering Research Deputy Assistant Commandant for Engineering and Division Logistics SHIP STRUCTURE SUB-COMMITTEE AMERICAN BUREAU OF SHIPPING (ABS) DEFENCE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT CANADA ATLANTIC Mr. Craig Bone Dr. David Stredulinsky Mr. Phil Rynn Mr. John Porter Mr. Tom Ingram MARITIME ADMINISTRATION (MARAD) MILITARY SEALIFT COMMAND (MSC) Mr. Chao Lin Mr. Michael W. Touma Mr. Richard Sonnenschein Mr. Jitesh Kerai NAVY/ONR / NAVSEA/ NSWCCD TRANSPORT CANADA Mr. David Qualley / Dr. Paul Hess Natasa Kozarski Mr. Erik Rasmussen / Dr. Roshdy Barsoum Luc Tremblay Mr. Nat Nappi, Jr. Mr. -

Ice Trials in Antarctica • New Rules on the Northern Sea Route • Processing Barge to the Arctic • Equipment for the Navy in This Issue

Arctic Passion News No. 1 | 2020 | issue 19 • Ice trials in Antarctica • New rules on the Northern Sea Route • Processing barge to the Arctic • Equipment for the Navy In this issue Page 4 Page 8 Page 11 Page 16 New rules on the Northern Xue Long 2 in Equipment for the Navy Barge for mining project Sea Route ice trials Table of contents From the Managing Director.................................. 3 Front cover New regime and regulations on the NSR...............4 Sami Saarinen spent six weeks travelling to Antarctica Xue Long 2 in successful ice trials.......................... 8 and back, onboard both of China’s icebreakers Xue Equipment for Navy corvettes.......................... ….11 Long and Xue Long 2. Read about his voyage and Safe and reliable shipping of crude oil................. 12 Xue Long 2’s ice trials on page 8. Feasibility study for Qilak LNG.........................….14 Aalto Ice Tank opens.............................................15 Contact details Pavlovskoe mining project.....................................16 AKER ARCTIC TECHNOLOGY INC Reducing ice friction since 1969 ...........................18 Merenkulkijankatu 6, FI-00980 HELSINKI Active Heeling systems.........................................20 Tel.: +358 10 323 6300 News in brief.........................................................21 www.akerarctic.fi Announcements....................................................23 Study tour to Gothenburg.....................................24 Join our subscription list Our services Please send your message to www.akerarctic.fi -

The Cutter the �Ewsletter of the Foundation for Coast Guard History 28 Osprey Dr

The Cutter The ewsletter of the Foundation for Coast Guard History 28 Osprey Dr. ewsletter 29, Spring 2010 Gales Ferry, CT 06335 Bill of Lading On Monday, February 1, 2010, three FCGH Regents—Phil The Wardroom Volk, Neil Ruenzel and Rob Ayer—gathered at the Acad- From the Chairman p. 2 emy Officers Club in New London, CT, to receive the dona- From the Executive Director p. 3 tion to the Foundation of a painting by William H. Ravell, National Coast Guard Museum p. 4 CWO, USCG (Ret.). Mr. Ravell is a well-known artist, with From the Editor p. 6 a specialty in maritime themes. Main Prop Hamilton’s Revenue Cutters p. 7 The painting is titled “The U.S. Coast Guard — Then and Coast Guard Academy p. 12 Now (1915 – 2010).” It depicts two cutters and two fixed- Keeper Richard Etheridge wing aircraft: USCGC Tampa (1912-1918), a Curtis Flying and Pea Island Station p. 14 Boat (ca. 1915), NSC Bertholf (commissioned 2008), and an Tsarist Officer in the U.S. HC-144A "Ocean Sentry" (in service). It bears the following Coast Guard p. 16 inscription from the artist: “Painted and presented to the Prohibition and the Evolution of the “Constructive Presence” Doctrine p. 17 Discovery of U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Alexander Hamilton p. 19 Quentin Walsh Centennial p. 20 Evolution of Coast Guard Roles in Vietnam p. 22 Historic First Visit By a Coast Guard Cutter to the People’s Republic of China p. 24 Speakings Tribute to William D. Wilkinson p. 26 Memorials Restorers Seek Clues to Ship’s History p. -

Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General

Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General The Coast Guard’s Polar Icebreaker Maintenance, Upgrade, and Acquisition Program OIG-11-31 January 2011 Ojfice o/lJlSpeclor General U.S. Department of Homeland Seturity Washington, DC 20528 Homeland JAN 19 2011 Security Preface The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office ofInspector General (OIG) was established by the Homeland Security Act of2002 (Public Law 107-296) by amendment to the Inspector General Act of I 978. This is one of a series of audit, inspection, and special reports prepared as part of our oversight responsibilities to promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness within the department. This report addresses the strengths and weaknesses of the Coast Guard's Polar Icebreaker Maintenance, Upgrade, and Acquisition Program. It is based on interviews with employees and officials of relevant agencies and institutions, direct observations, and a review of applicable documents. The recommendations herein have been developed to the best knowledge available to our office, and have been discussed in draft with those responsible for implementation. We trust this report will result in more effective, efficient, and economical operations. We express our appreciation to all of those who contributed to the preparation of this report. /' -/ r) / ;1 f.-t!~ u{. {~z "/v"...-.-J Anne L. Richards Assistant Inspector General for Audits Table of Contents/Abbreviations Executive Summary .............................................................................................................1 -

Towards an Automatic Ice Navigation Support System in the Arctic Sea

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Towards an Automatic Ice Navigation Support System in the Arctic Sea Xintao Liu, Shahram Sattar and Songnian Li * Department of Civil Engineering, Ryerson University, 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada; [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (S.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-416-979-5000 Academic Editors: Suzana Dragicevic, Xiaohua Tong and Wolfgang Kainz Received: 18 January 2016; Accepted: 8 March 2016; Published: 14 March 2016 Abstract: Conventional ice navigation in the sea is manually operated by well-trained navigators, whose experiences are heavily relied upon to guarantee the ship’s safety. Despite the increasingly available ice data and information, little has been done to develop an automatic ice navigation support system to better guide ships in the sea. In this study, using the vector-formatted ice data and navigation codes in northern regions, we calculate ice numeral and divide sea area into two parts: continuous navigable area and the counterpart numerous separate unnavigable area. We generate Voronoi Diagrams for the obstacle areas and build a road network-like graph for connections in the sea. Based on such a network, we design and develop a geographic information system (GIS) package to automatically compute the safest-and-shortest routes for different types of ships between origin and destination (OD) pairs. A visibility tool, Isovist, is also implemented to help automatically identify safe navigable areas in emergency situations. The developed GIS package is shared online as an open source project called NavSpace, available for validation and extension, e.g., indoor navigation service.